The Tragic True Stories Of The Other Great Fires Of London

There's an old saying: When it rains, it pours. To those living in London in the 1660s, it didn't just pour, life was a torrential hurricane of some of the direst conditions anyone could expect to live through. Historic UK puts things in perspective with this not-so-fun fact: Those who lived through the Great Fire of 1666 had already survived the Black Death.

The Lord Mayor's response to news of a fire breaking out around London Bridge in 1666 was less than stellar. After basically suggesting the fire wasn't a big deal at all — and even a woman could put it out — it quickly engulfed hundreds of homes ... and people started realizing it was a big deal after all. Attempts at destroying rows of buildings to create firebreaks failed, people fled to the River Thames in an attempt to escape the flames, and by the time it was all over, an estimated four-fifths of London was little more than charred ash.

London was, of course, rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666, but here's the thing — that's not the only time the city was destroyed by fire. Throughout the city's long history, there have been an almost unlikely number of massive fires that have changed the landscape of London in a physical, and sometimes social, way. It's happened to "The Big Smoke" again and again ... so, let's take a look at some of the many times London has been shaped by fire.

Boudica's revolt

Per Britannica, London was founded in the year 43. That's when the Roman army decided to set up camp north of a pretty large river, and they called their settlement Londinium. It wasn't there for long.

At the time, according to Historic UK, it was the nearby Camulodunum that was the Roman British capital city, and it was this city — now modern-day Colchester — that was the main target of the wrath of Queen Boudica. She kicked off an Old Testament-style fire-and-brimstone campaign of mass destruction against the Romans in the year 60. At Camulodunum, Boudica's troops were opposed by civilians, retired veterans, and a reported 200 soldiers sent up from Londinium, so one can only imagine how well that worked out for Rome.

After the indigenous Brits murdered and burned their way through Camulodunum, they headed to Londinium to burn that to the ground, too — and they did. Boudica's army killed an estimated 70,000 people and torched the city so completely that, according to New Scientist, archaeologists excavating London have found a layer of ash and sediment clearly marking the precise time of the fires that destroyed the city on both the north and south side of the Thames. While many of the buildings were made of timber, Archaeology Magazine says even the clay buildings and walls were destroyed, leaving the young city nothing more than blackened and burnt remains.

The Hadrianic fire

Everyone's had those super embarrassing moments that feel like they're going to live on in infamy for the rest of history, but let's put things in perspective. Next time one of those moments happens, remember that history has forgotten events that are a lot bigger — like the fire that destroyed a good portion of London in 125 or 126.

According to "London in the Roman World," archaeologists know that London burned in a really big way sometime around 125-6 A.D. and was rebuilt in the following few years. Destruction was so complete that it was on the same scale as the damage done by Boudica, and it's believed that the evidence points to a large-scale war. Only, no one knows anything about it.

There are some interesting theories, though. While some think the burning of London in what's become known as the Hadrianic fire was an act of war, Dr. Dominic Perring of the Institute of Archaeology has another idea (via The Past). Perring suggests that it wasn't war but rebellion and that the fire marked a massive uprising.

In addition to the remains of the city, caches of skulls have been discovered, too. Were they the skulls of the executed rebels? Has it been forgotten because the Romans simply wrote it out of their history? No one's sure — but we do know that the city was rebuilt fairly quickly, for the first time with masonry buildings.

The great fire of 1087

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a pretty fascinating read: It's basically a year-by-year summary of English history through the middle of the 12th century (via The Medieval and Classical Literature Library), written in Anglo-Saxon or Old English. The text covering the 11th century (via Yale Law School) starts with things like a Danish invasion, conflict with the French, and a famine "so severe that no man ere remembered such."

Fast forward to 1087, and it was a big year. It was so busy, in fact, that a fire that destroyed a huge section of London, which included St. Paul's Cathedral, only got a few sentences. The chronicle records: "...before harvest, the holy minister of St. Paul ... was completely burned, with many other ministers, and the greatest part, and the richest of the whole city."

Britannica says that along with St. Paul's — which, incidentally, had already been rebuilt for the third time in 962 — this fire destroyed the majority of London's wooden homes and buildings. Rebuilding was an opportunity for change, but it didn't change as much as it might have. Open sewers were installed and while some of the homes were rebuilt from stone, most were still made from wood.

St. Paul's Cathedral, meanwhile, would remain unfinished for an almost ridiculous amount of time: until 1314, according to Medievalists.net. Another London fire would halt progress in 1135, and it was only consecrated in 1240. It wasn't finished yet, but there comes a point where you've just got to say, "Oh, the heck with it."

Great Fire of Southwark (1212)

While London's Great Fire of 1666 is arguably the most famous, Historic UK says that only about six people died in the blaze. More than 400 years earlier, another fire not only destroyed huge sections of London on either side of the River Thames, but it killed many more people. Some (perhaps exaggerated) estimates suggest as many as 3,000 people died in the fire of 1212 — and there's a horrifying reason why.

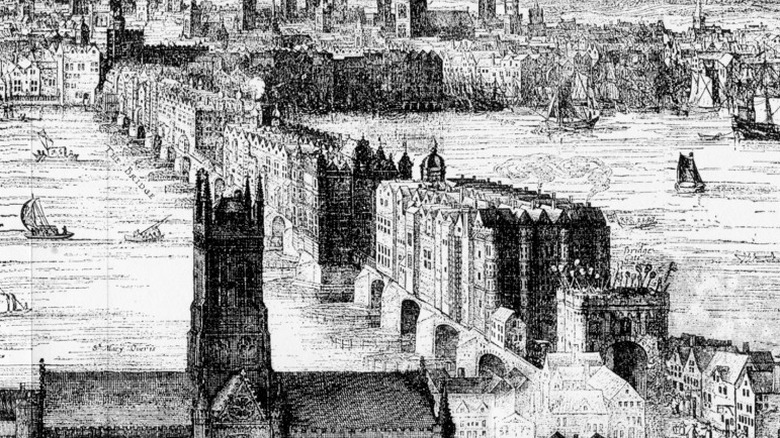

Per Sky History, it's not clear exactly where or how the fire started in London, but historians can say that it started somewhere in Southwark, and it moved incredibly fast. As the fire spread, it reached all the way to London Bridge, and then, it crossed.

At the time, it wasn't just a bridge, it was an entire community. King John gave permission for buildings, shops, and homes to be built along both sides of the bridge, and it quickly proved not to be the best idea in the world. The bridge became a traffic jam of people — fleeing from the south, running to help from the north — and when the buildings on the bridge started to catch on fire, those people died.

Some people jumped into the Thames, but it proved just as deadly as the fire. Some drowned, while others were crushed to death as they tried to climb onto boats. By the time the fire was finally extinguished, it had burned so hot and for so long that it had rendered the stone bridge unusable.

The Ratcliffe Fire (1794)

Clovers Barge Yard sounds like an idyllic portside hub, but in July of 1794, it was the farthest thing from idyllic in London town. According to Historic UK, that's when a single kettle of pitch boiled over.

No one was keeping an eye on things, and even if they had been, they may not have been able to stop what happened next. The fire spread quickly through the East London district of Ratcliffe, and it wasn't long before it engulfed a nearby barge that was, unfortunately, loaded with the highly explosive raw ingredients for making gunpowder.

The following explosion scattered burning saltpeter all over the surrounding industries, which just happened to include highly flammable buildings like lumber yards and a rope storage facility. In what seems like a cosmic attempt at seeing how many flammable things can be jammed into one location, narrow streets and shoulder-to-shoulder homes encouraged the spread, and by the time the smoke cleared, around 1,400 people were homeless and there was a single building still standing: No. 2 Butcher's Row.

The Burning of Parliament (1834)

Back in 1826, the UK Parliament discontinued the use of wooden tally sticks for their system of bookkeeping and accounting. By 1834, the wooden sticks were still around, and anyone can see where this is going.

Anyone, that is, except for the workmen instructed to get rid of all the sticks, who were told by the Clerks of Works to burn them in the House of Lords' basement stoves. So, they did, and even though visitors observed that "it had gotten rather toasty in here today," everyone still extinguished the furnaces, packed up, and went home at 5 p.m. Within the hour, both the House of Lords and the House of Commons weren't just toasty, they were burning to the ground.

And here's the weird thing: According to the History of Parliament, over the centuries, added construction and expanded buildings had turned Parliament into a nightmarish complex of buildings that even Christopher Wren couldn't fix. As it burned in 1834, what fell away were the wooden buildings on the outside. It ended up revealing some of the gothic structures beneath, like St. Stephen's Chapel. Still, it was a traumatic thing to see: flames turned into explosions — which turned into more flames — and hundreds of firefighters were on the scene for five days.

Parliament was, of course, rebuilt, and no one was prosecuted. The prime minister, the Hon. William Lamb, dubbed it "one of the greatest instances of stupidity upon record."

The Tooley Street Fire (1861)

The Tooley Street Fire of 1861 spread incredibly fast, and as it burned along the shores of the River Thames from London Bridge down Cotton's Wharf, tens of thousands of people turned up to stand by and watch ... including the London Fire Engine Establishment, the predecessor to the London Fire Brigade. They got there incredibly quickly, but the tide was so low that they couldn't get to the water they needed. And so, it burned — and by the time they could get to the water, it was so hot they couldn't get close to the flames.

Historic UK reports the blaze started in a Cotton's Wharf warehouse and quickly spread through other warehouses in that area of London. It was helped along by the highly flammable contents, including jute, cotton, tallow, and an estimated 500 tons of saltpeter. Also helping was the fact that most of the warehouses' iron fire doors had been left wide open, and it led to damages in the neighborhood of around $200 million.

According to British Art Studies, the fire was actually well documented in illustrations and paintings — as was the presence of the crowd that turned out to watch, buying snacks and drinks from the wandering food vendors who also showed up.

Notably, the blaze claimed the life of James Braidwood, a surveyor and a firefighter who pioneered some of the techniques still in use today. It also led to an overhaul in fire safety, warehouse storage protocols, and insurance guidelines.

The frozen fire of Butler's Wharf (1931)

London's Metropolitan Fire Brigade was officially formed in 1866 as a part of the overhaul to fire services that happened in the aftermath of the Tooley Street Fire. (As an interesting side note, the Firefighter Foundation says that the earliest recruits were ex-sailors, as they were used to grueling work, bizarre hours, and heavy lifting.)

In 1931, they faced what the London Fire Brigade called their biggest challenge to date: the frozen fire at Butler's Wharf. It took more than 1,100 firefighters to contain the fire, but they did — to a seven-story warehouse filled with rubber and tea. As if the smell of burning rubber wasn't bad enough, they were also forced to deal with freezing temperatures.

It was so cold that hoses froze, firefighters couldn't hold them, and chipping away at ice and icicles dragged the entire thing out into a two-day battle with the blaze. In the end, damages amounted to somewhere in the neighborhood of $300,000, and by the time the fire was out, the entire complex was covered in inches of ice.

The Crystal Palace fire (1936)

The Great Exhibition of 1851 is the sort of thing that would be absolutely worth a place on the time travel bucket list. Organized mainly by Prince Albert, the exhibition was a massive undertaking that showcased all the best that Victorian England had to offer (via Historic UK).

Much of it was housed in a huge building called the Crystal Palace: At 1,850 feet long, it was about five times the length of a standard American football field. Millions of people visited, and when it was relocated to South London after the exhibition, the London Fire Brigade says that the palace was expanded and became the largest building in the world.

Sadly, it wasn't the draw the owners had hoped for, mostly because Victorian-era workers didn't have the free time to visit. Then, in 1936, manager Sir Henry Buckland noticed a flickering light at one end of the building. It was a fire ... in a building that had already been diagnosed as having a gas leak.

Iron, says the LFB, melts at somewhere around 1500 Celsius, or 2700 Fahrenheit. Based on video footage shot at the time, the iron supports weakened, then collapsed as firefighters were only able to stand and watch as this crowning achievement of Victorian art, architecture, and science fell to the flames.

The grounds are still a park, and per History Today, although there have been rumors of plans to rebuild the entire structure, that hasn't happened.

The Second Great Fire of London (1940)

The Museum of London called December 29, 1940, the second great fire of London, and so did George Britchford. He was a firefighter on the front lines on the night that German bombers dropped more than 124,000 bombs on London.

In a letter to his wife (who had been evacuated to Newcastle with their two children), Britchford wrote: "... it's impossible to describe the scene that was there ... it seemed as if the whole of London was on fire the great fire of London was nothing like it, we pumped water up from the Thames about 2 miles away ... we fought the fires till we could hardly hold the hose and then we had a rest for a while and back at it we went."

David Britchford, George's son, donated the letter to the museum and said that after he discovered it following his mother's death (at 103 years old), it was new insight into what his father went through in London in 1940. He knew about the souvenirs — including a clock hand-bent and melted by fire, and an incendiary bomb — but reading his father's words about the long hours and seeing buildings collapse on and kill his fellow firefighters put things in perspective.

The London Fire Brigade says the Blitz was 57 days of nonstop bombing, with around 10,000 fires breaking out in the first 22 of those days. By the end, the fire brigade would answer more than 50,000 calls and lose 327 of their own.

Smithfield Market Fire (1958)

It can be a little mind-numbing just how old some of the locales scattered across London are. Take the Smithfield Market. The City of London chartered this area — used mostly as a marketplace for livestock — in 1327, and it had been in use for several hundred years before that.

The site was under constant development, and in 1958, a fire broke out in the labyrinthian complex. "Labyrinthian" is possibly the last word anyone wants to hear alongside a story of a fire that burned for three days, but here we are.

According to the London Fire Brigade, those who were the first on the scene found smoke coming not from the market, but from the tunnels beneath it. That's where the cold storage was, and it's also where Jack Fourt-Well and Richard Stocking disappeared. They didn't return and were later discovered where they had collapsed, beneath the hanging carcasses that had been slated for feeding London's people.

The fire raged in London for days, and it took 389 vehicles and 1,700 firefighters to finally extinguish it. Of those, about 50 were treated for injuries related to smoke inhalation, and per the Fire Brigades Union, the consequences of the fire led to a complete overhaul of breathing apparatus standards.

The King's Cross Fire (1987)

Deadly fires aren't just the stuff of ancient history, either, and in 1987, the London Underground saw what the British Transport Police describe as the system's deadliest fire to date. It started accidentally: A dropped match ignited grease and garbage beneath a wooden escalator, and the subsequent fire — and fireball — killed 31 people and severely injured another 100.

At the time, the 124-year-old mass transit system had never had an event that led to mass casualties, reports the BBC. It changed in a pretty awful way: Daemonn Brody was among the injured, and recalled hearing someone shouting to get out, then chaos, then feeling a ball of fire engulf his feet and legs first. "I was upset," he said later. "I knew I was dying and that nobody would know I was down there."

Around 150 firefighters would spend hours trying to help the trapped, injured, and screaming people up to the paramedics for treatment, and as they did so, they braved temperatures that topped out at about 600 Celsius, or 1112 Fahrenheit. Heat rose as trains passed, protective gear melted, and one firefighter died. Since then, massive improvements across the board — changes spurred on by the fire — mean that the London Underground remains one of the safest subway systems in the world.