The Chilling Truth About Mass Murderer Jack Gilbert Graham

When Daisie King boarded United Airlines Flight 629 on November 1st, 1955, en route from Denver, Colorado, to the Pacific Northwest, she had no idea that a betrayal would set in motion a chain of events that resulted in her death, as ABC 7 details. A lifetime of resentment and a desire for an insurance windfall set her son John "Jack" Gilbert Graham on a murderous mission to end her life by any necessary means, resulting in an act of airline destruction that killed King alongside over 4 others onboard the fatal flight.

The act shook the local community, provoking a media firestorm and a massive Federal investigation that changed Colorado and national United States history forever. The result is a teeth-clenching story of lies, betrayal, and mass murder that produced a set of copycat crimes, new U.S. legislation, and helped spark the prolific wave of televised trials that we see to this day.

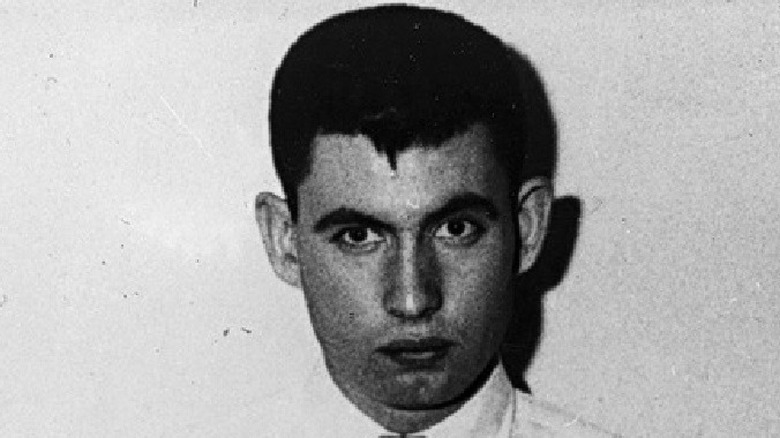

Jack Gilbert Graham had a tragic childhood

As Andrew J. Field details in "Mainliner Denver: The Bombing of Flight 629, John "Jack" Gilbert Graham was born on January 23, 1932, during the heart of the Great Depression, to Daisie E. King and a mining engineer named William Graham. He was King's second child and William Graham's first, and in the era of his infancy the economic context of the Depression meant his father's mining pursuits never quite landed. As chronicled in Brian K. Trembath's retrospective in the Denver Public Library's history blog, William Graham and King separated when Jack was only 18 months old, and his father died of pneumonia when the boy was 3.

In this period, King often worked while her grandmother took care of Graham and his half-sister Helen Ruth Gallagher. When Graham's grandmother died, the boy was sent to live at the Clayton College for Boys (an orphanage for "poor white male orphans ... born of reputable parents," according to "Mainliner Denver: The Bombing of Flight 629").

His mother kept him at an orphanage despite growing rich

Daisie King herself was raised in a normal middle- to upper-class family, with her father rising from humble beginnings as a teacher to become not only a state representative but district attorney and district court judge in Colorado, according to Andrew Field's "Mainliner Denver: The Bombing of Flight 629." moving his After moving to Denver, Daisie married a man named Tom Gallagher in the early 1920's, giving birth to her first child, Helen. She and Gallagher divorced not long after. Eventually Daisie married William Graham, and the pair moved frequently as they chased construction job after job before Jack Graham's birth.

After Jack's move to the orphanage, Daisie married a third time to wealthy rancher Earl King in 1941. This dramatically improved her finances, yet she never chose to retrieve Jack from the orphanage. By the time she eventually inherited Earl's considerable wealth on his death in 1954, her son was an adult and married with kids.

It isn't like he never saw his mother during his time at Clayton — he did spend holidays and vacations on his stepfather's ranch, only to be continually returned to the orphanage during the school year, as per Edward C. Davenport's "Eleven Minutes: The Sabotage of Flight 629."

When Graham was 13, he stayed awhile with one of his stepfather's neighbors in another unstable stint that failed to work out. As Davenport notes, young Graham had difficulty grasping why he could never simply stay with his mother.

He was court martialed and discharged from the Coast Guard

Jack Graham completed the ninth grade in public school but at the time did not receive a high school diploma, as per the FBI. According to "Eleven Minutes: The Sabotage of Flight 629," by Edward C. Davenport, he lied about his age to enlist in the Coast Guard, where he served from April 1948 to January 1949. During that time, he went AWOL 63 days, reports the FBI.

At his court martial hearing, Graham admitted he was tired of having to answer to his higher ups, so he went partying instead. "I don't feel sorry about it; but I'm not happy about it," he explained. "I don't want a bad conduct discharge." He was sent to a hospital for neurological tests following the hearing and was later honorably discharged. According to Davenport, Graham claimed he'd been given shock treatments at the hospital, but the Coast Guard didn't confirm those allegations. Instead, his records offered a different insight into his behavior, noting that Graham was immature, displayed poor judgment, and exhibited impulsive behavior.

As the FBI notes, Graham did receive his diploma upon passing entrance exams at Denver University, where he met and married later married in 1953 fellow student Gloria Elson. His life on the surface appeared to be as a family man, with a devoted wife and children (via Andrew Field's "Mainliner Denver: The Bombing of Flight 629"). In 1954, his mother finalized the purchase of a new home for herself, her son, and his wife in preparation for their second child in February 1955.

However, beneath this troubled, aimless history of starts and stops was a violent reputation. Graham's half-sister later reported to the FBI that Graham had anger issues, a dark sense of humor, and had enacted violence on a handful of occasions on both her and his wife.

He was a dedicated scam artist

Scattered throughout Jack Graham's history is a growing series of fraudulent activity, as chronicled by the FBI. In early 1951, he was employed as a payroll clerk when he fraudulently stole a set of blank checks. Filling out 42 of the checks for $100 each, he forged the name of the company owner, landing him on the local "most wanted" list. Of his stolen $4,200, Graham spent $2,000 and went on the run to Texas.

In Texas, the growing criminal quickly ran afoul of the Texas legal establishment when he was arrested in Lubbock on September 11, 1951, for illegally transporting whiskey. This new criminal act came with a sentence of 60 days in county jail before he was released to Denver County for the forgery charge. He was convicted on November 3, 1951, but the conviction was suspended, with Graham placed on probation for five years. He paid financial restitution from 1952 until 1955.

What's clear in this period is that his early career life easily gave way to a stream of illegal get-rich-quick schemes, fleeing a botched forgery attempt that was immediately followed by illegal liquor transportation. It's a trail of fiscal-minded scheming that, tragically, did not stop.

His illegal plans became larger and more dangerous

While paying off his considerable debt, Jack Graham worked as a heavy-duty equipment mechanic between January 1953 and December 1954, as per the FBI. After procuring a home for her son and his wife to help them raise their family, Daisie King then built a drive-in restaurant for Graham to manage. In the spring of 1955, the pair opened the Crown-A drive-in.

In their investigation, the FBI highlighted that King and Graham fought regularly over management of the restaurant. The restaurant had experienced considerable vandalism in May, shortly after it opened, and in September 1955 an explosion occurred there. In early FBI interviews, Graham volunteered that a gas line had been disconnected and caused the explosion. The Denver Public Library highlights that Graham later admitted that the Crown-A explosion was an attempt at an insurance fraud scheme.

The FBI also reported around the same time Graham's 1955 Chevy truck got hit by a train, and sources interviewed by the FBI suggested that the sabotage was also an effort to collect insurance. The truck's credit manager even told investigators that Graham commented on the ease of placing a bomb on an airplane and blowing it up.

He used 25 sticks of dynamite to build a disguised bomb

FBI interviews with neighbors and his wife, Gloria Graham, reveal that, in November 1955, Jack Graham had gone shopping for what he said was an artistic tool kit intended for his mother as a Christmas present. According to Gloria, on November 1 a package was brought into the house and taken into the basement where Daisie King was packing for her flight. While Jack did pack a wrapped present into his mother's suitcase, it tragically wasn't a tool kit.

On later questioning, he admitted to building and planting a time bomb that blew up United Airlines 629, placing it in his mother's suitcase. The bomb was made of 25 sticks of dynamite, two primer caps, a timer, and a six-volt battery — all materials he bought from various supply stores in October. Jack knew what he was doing with dynamite –- one FBI interviewee confessed Jack discussed having performed demolition work in the U.S. Navy, and his half-sister admitted he'd once casually joked about using dynamite to blow off a stuck bolt.

Without anyone the wiser, Jack Graham built the bomb while his mother was arranging final trip details, placed it into her suitcase, and with his wife and children in tow to see King off, Jack drove his mother to the airport and dropped the family off at the terminal door. He drove the car to the parking lot, set the timer on the bomb, and took the suitcase to be weighed and placed on the plane.

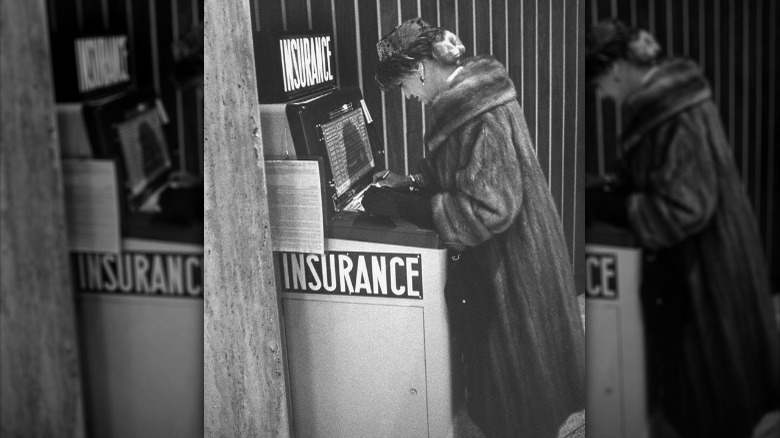

He took out multiple insurance policies on his mother

With the bomb packed away, Jack Graham proceeded to purchase several travel insurance policies from airport insurance vending machines, which were widely available in mid-century America, according to the Denver Public Library. According to the FBI, a search of Graham's home revealed three such policies: a $37,500 policy on Daisie King denoting Graham as the beneficiary, and two $6,250 policies on King with her sister and daughter as beneficiaries.

Interestingly enough, the insurance policies were one of the first avenues of investigation the FBI pursued. Their investigation revealed a number of policyholders on board Flight 629, but due to a holiday weekend it was impossible to check all insurance providers immediately. The policies placed for King were among those discovered later. In initial FBI questioning, Graham couldn't explain why he mailed a massive trip insurance policy to himself (besides noting that he'd mailed two other policies to his sister and aunt). Once again, he attempted to use insurance fraud for a financial windfall, but this time motivated directly by a lifetime-long grudge against his mother.

He murdered 44 people without remorse

As the FBI's investigation details, United Airlines Flight 629 left for Portland, Oregon, on November 1, 1955, at 6:52 p.m. Eleven minutes later, 39 passengers and five crew were dead. A tremendous explosion occurred in the cargo department of the plane, cleanly severing its tail section and causing a flare to separate and ignite. A secondary explosion occurred when the plane's engines and forward compartment hit the ground, gauged to most likely be an explosion in the fuel tanks.

Upon the plane's initial departure, a neighbor heard that Jack Graham turned visibly white and ill upon the plane's departure, and his first reaction to hearing the plane had crashed was to utter the statement "that is it." The Denver Public Libary recounts his later confessional admission to Agent James R. Wagoner that, "I watched her go off for the last time. I felt happier than I ever felt in my life."

His single regret? That a 10-minute delay caused the plane to explode over farmland rather than the intended (harder to investigate) Rocky Mountains. When he was interviewed by psychiatrists about the body count, the FBI quotes Graham as cooly saying, "The number of people to be killed made no difference to me; it could have been a thousand. When their time comes, there is nothing they can do about it.

Evidence of his guilt builds

The plane's explosion had indications of sabotage, and the FBI closely looked at every passenger for clues as to who was responsible, according to their investigation. Various chemical deposits were found on the wreckage, like sodium carbonite, nitrate, and sulfur compounds –- precisely the only solid residue expected from the explosion of dynamite — as well as burned and soot-covered fragments that were later identified as part of a six-volt battery.

One of the most interesting things revealed in the subsequent investigation is that, while almost nothing was discovered from the luggage of Daisie King, she was carrying on her person a number of particularly interesting personal effects found on or near her body (suggesting they were in her handbag, on her person). These included personal letters, newspaper clippings about Jack Graham's forgery conviction and placement on Denver's "most wanted" list, and more. Discrepancies between Graham and his wife's statements proved the final stray, leadig the FBI into his probable guilt.

He unsuccessfully tried to be declared insane

Jack Graham was arraigned in Denver District Court on December 9, 1955. After his arrest, he transferred the majority of his property to his wife, declared himself unable to pay for counsel, and accepted court-appointed representation, according to FBI records. He was charged with the murder of his mother and submitted the pleas of "innocent" and "innocent by reason of insanity."

After a series of interviews to determine his mental state, psychiatrists concluded Graham was putting on an act, claiming his "patchy anmensia, intermitent disorientation, and absurd as well as correct answers to simple arithmetic problems" were all simulated to make him appear crazy, writes Andrew Field in "Mainliner Denver: The Bombing of Flight 629." Graham was found sane enought to sit trial and was returned to the Denver County Jail.

By all accounts he was a well behaved prisoner that chatted with guards and spent his time reading, yet on February 10, 1956, he was found on the floor of his cell with his socks twisted around his neck. His suicide attempt failed (and was apparently a ploy to get the doctors to change their mind, notes Field), but from then on he was transferred back to a psychiatric unit at Colorado General Hospital with 24-hour surveillance by a team of guards. Subsequent conversations with psychiatrists saw Graham forthrightly confess to his mother's murder, including the process of constructing and placing the bomb, directly confirming what the FBI had come to expect.

The FBI had a mountain of evidence, including unique reconstructions

Jack Graham dropped his insanity plea on February 24, 1956, and his trial commenced a couple of months later on April 16, 1956. His trial set the all-time record for the number of jurors examined for a Colorado trial, with 231 examined for bias, according to the FBI. Over the duration of a 15-day trial, witnesses testified to his purchase of dynamite and other bomb-making materials, attempted to show that the blast could have been caused by dynamite alone, and described the events leading up to the plane's takeoff, explosion, and crash. Graham's character, actions, and statements were submitted to scrutiny. Most damning, of course, was his willingly signed confession. As Andrew Field in "Mainliner Denver: The Bombing of Flight 629" notes ,Graham also refused to testify on his own behalf.

In the trial, it was also revealed that he approached the owner of an electric company to work cheaply from a desire to get experience. His last day involved a suspicious inquiry about timing devices with batteries that would not exceed two hours. The trial also involved a massive reconstruction of the Mainliner airplane in a large Stapleton Airfield hangar, one of the largest reconstructions done up to that point in history, as per the Denver Public Library.

As per the FBI, it only took the jury a little over an hour to convict Graham. After all was said and done, Graham was executed Friday, January 11, 1957.

His widow received considerable life insurance afterward

One would think that a convicted mass murder, whose murder was motivated by resentment and insurance fraud, wouldn't be able to pass on any insurance benefits to his family in the event of his execution. That assumption would be incorrect. His wife, who in the course of the investigation and trial had almost universally been treated as merely an innocent and sympathetic wife who loved her husband (despite declining to attend the execution, according to the Denver Public Library's history blog), nonetheless received a relevant insurance windfall following his execution.

After complex litigation with Daisie King's estate and the insurance company underwriting the insurance policy placed on her trip, Gloria Graham was able to receive a roughly $10,000 policy (over $100,000 today). It's a final bit of irony in Jack Gilbert Graham's story — after a short lifetime of constant insurance fraud attempts, the only true insurance windfall his actions ever produced occurred as the result of his own death. He never saw a dime of it.

His crime has a massive impact

Propelled by resentment and a desire for ill-gotten gains, Jack Gilbert Graham's nefarious mass murder left an indeliable mark on Colorado and national history for years to come. According to the Denver Public Library, the crime sparked a wave of insurance-motivated airline bombings. Consequentially, on July 14, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law Section 32 of the U.S. Criminal Code, making the destruction of aircraft and aircraft facilities a crime for the first time under United States law.

The aftermath of the heinous crime also holds another distinction, as one of the key court cases that sparked the prolific phenomena of televising trials. While the first televised murder trial in U.S. history is the December 6-9, 1955, trial of Harry Washburn in Waco, Texas (according to KWTX News), Graham's trial became the first televised criminal trial in Colorado history (though not live) and one of the first in U.S. history, according to online legal news site Law Week Colorado.