Here's What It Was Like Going To A Speakeasy During Prohibition

If you've only ever had a passing familiarity with the concept of speakeasies, then you might have only an impression of some glittering, decadent party straight out of "The Great Gatsby," full of carefree flappers and lively dancing. To be fair, some of that fantasy is based in truth, as underground nightlife culture did see increasingly liberated women as well as the spectacle of both the Charleston and some really excellent jazz music.

In a large way, it was all thanks to Prohibition. After generations of lobbying, the anti-alcohol temperance movement finally got its way with the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Along with the Volstead Act, the amendment forbade the manufacture, sale, and distribution of "intoxicating liquors" across the nation. Of course, federal law wasn't really going to stop people who wanted to drink, and so many bars and saloons went underground and became speakeasies.

Supposedly, the term "speakeasy" actually predated the 1920 onset of Prohibition. According to "Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era," multiple stories link it to bar proprietors operating without a license who would tell rowdy customers to "speak easy," lest the police come in to shut it all down and ruin their good time.

But what was it really like to make your way to a speakeasy? Was it as fun as today's media would have you believe, or was the experience more layered and tricky? Here's what is was really like going to a genuine speakeasy during the Prohibition Era.

Getting into a speakeasy could be complicated

The first step in the Prohibition-era speakeasy experience was, naturally enough, finding a speakeasy. But simply knowing that one existed nearby wasn't enough. The idea of the speakeasy was predicated on some level of secrecy, though many of the larger ones eventually became open secrets in their cities and towns. Essentially, you had to show that you were safe and not a snitch or police officer hoping to close down the joint.

Speakeasies had different solutions to this problem. According to the The Mob Museum, a few may have used this as a money-making opportunity, asking visitors to become members and pay dues before they could enter. Others resorted to the old classic of passwords, shared among loyal patrons and anyone deemed acceptable for attendance. Of course, there was always the tactic of hiring bouncers who had decent memories and could recognize regulars without all of the bother of secret codes.

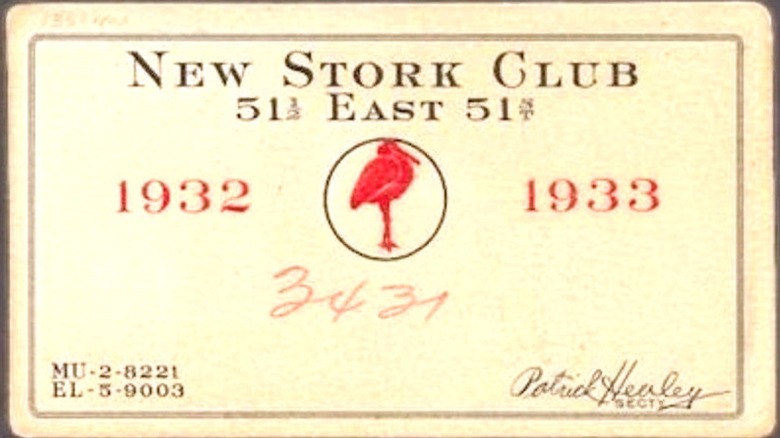

Some speakeasies even went the seemingly daring route of leaving a paper trail with admission tickets. As Slate reports, people hoping for admittance could simply present a club-issued card to the bouncer. One particular collection spans a 13-year period and covers just one section of Manhattan in a city that was rife with illegal drinking spots. Perhaps that made it easier for bouncers who would have dealt with a diverse and bustling clientele in New York City — though there were likely sometimes questions as to how the presenter got hold of their card.

Patrons had to manage speakeasy doors

While speakeasies wouldn't be advertised by flashy signs or glowing neon lights, there were a few telltale signs at the front door that could tip savvy people off to the goings-on inside. Sometimes, it was as simple as paying attention to paint colors. According to the The Mob Museum, a number of speakeasies employed distinctive (though one assumes not too obvious) green doors. At any rate, the image of a green door became associated with underground drinking establishments. Two such Chicago speakeasies became known for their verdant entryways, namely the Green Door Tavern (which, in a score for efficiency, also happened to house yet another speakeasy in the basement) and the Green Mill Cocktail Lounge. The former was partially owned by a gang associate of notorious Chicago mobster Al Capone. Even smaller joints, like the Green Door of Fortescue, New Jersey, went by the name (via "Around Fortescue").

If a green door was a bit much for some speakeasy managers, the entrance might still require some practical touches unique to the operation. Some employed the so-called "Judas hole," a peephole that allowed the doorkeeper to take a look at whoever was knocking without themselves being seen. It's now such a part of Prohibition's visual history as to be a cliché, but it's clear that some speakeasies really did use these peepholes to make sure that the police or other professional party-poopers weren't standing on the doorstep (via "Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era").

Some speakeasies catered to the glitterati

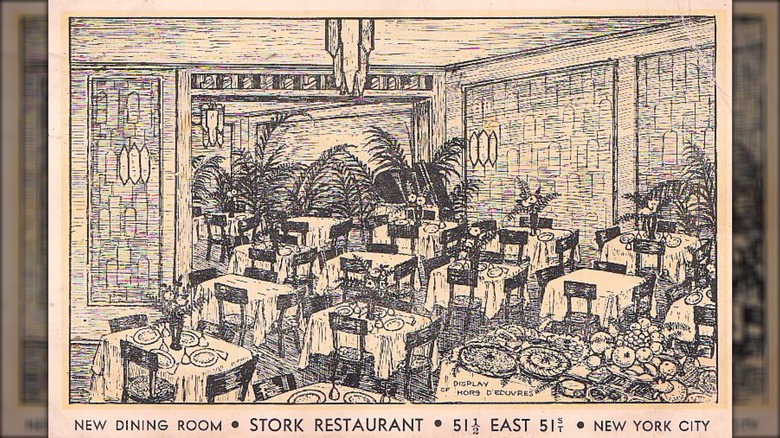

If partiers knew the right people and were of the "right" sort themselves, then the speakeasy evening could be quite glamorous. In New York City, one of the most spectacular of these high-flying speakeasies was the Stork Club. It opened in the midst of Prohibition in 1929 (via the Gothamist). Though it had to move after law enforcement temporarily shut it down, the Stork Club managed to not just survive Prohibition, but thrive. By 1936, it was bringing in $1 million per year. Bootlegger Sherman Billingsley — who helped found the club as a speakeasy with some shady mobster characters — spent many years after Prohibition rubbing shoulders with the famous and powerful. Billingsley even reportedly lavished expensive gifts upon some of his most favored visitors, like a bottle of perfume presented to actress Joan Crawford.

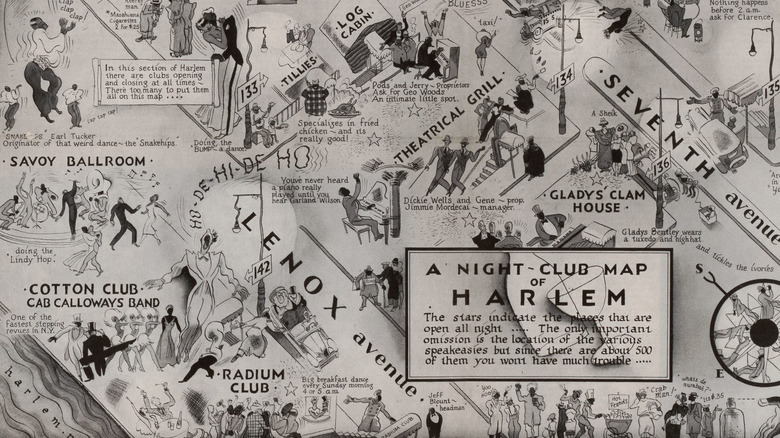

New York, as it turns out, was lousy with high class speakeasies. There was the Cotton Club, a glamorous cabaret-style performance venue that drew white partiers to Harlem (though, as Britannica notes, the audience was very much not integrated). The 21 Club was also a notorious spot for those who could afford it, with the owners making a splash on New Year's Eve 1929 with a tuxedo-clad affair awash in Champagne and demolition equipment. According to Thrillist, the boozy guests were encouraged to take apart the old venue and join the owners in newer, nicer digs — where, of course, the best smuggled alcohol would be available.

Speakeasies complicated racial norms

In many public and private spaces of Prohibition America, segregation was a given. Yet, when it came to the world of the speakeasy, the racial norms of the era could become complicated. According to the Mob Museum, it wasn't entirely unheard of for patrons of various skin colors and ethnic backgrounds to mingle in a speakeasy, listening to jazz music pioneered by Black musicians. Eventually, these became known as "black and tan" clubs, a term that had been around for decades. The phrase became fairly popular, to the point where one Seattle establishment, formerly known as the Alhambra, changed its name to the Black and Tan in 1933.

Yet, this shouldn't be taken to mean that speakeasies were somehow free of racial prejudice. According to "Last Call," the "hooch joints" of Harlem were typically open to just about any Black patron that wanted to enter. A white person, however, was often viewed with suspicion, as they might be part of a clumsy attempt by the authorities to infiltrate and shut down the illegal drinking establishment. Likewise, the Mob Museum notes that some of the more exclusive speakeasies allowed Black people to enter — but far more often as performers and waitstaff than as patrons to be served.

The famous Cotton Club, located in Harlem, featured legendary Black performers like Duke Ellington. However, only whites were allowed in the audience (via Britannica).

Speakeasy culture encouraged live music

Though speakeasies were certainly not sanctioned by the local chambers of commerce, the fact remained that they were businesses that needed to make money in order to keep operating. And, like so many businesses before and after Prohibition, that meant competition. Sometimes that meant delving into the dangerous world of the mob; other times, however, it meant taking part in an artistic arms race. In other words, it was just the right time for jazz to shine.

The Mob Museum notes that jazz had already been around for some time prior to Prohibition, but it was the abolition of alcohol nationwide that created a lively and lucrative nightlife culture. Most patrons, as it turned out, didn't want to drink their liquor among muttered conversations or in grim silence. For some of the lower-class spots, one of the newfangled "jukeboxes" would do, so long as the records kept playing and encouraging some dancing. But if someone was dressing up to the nines in a suit or evening gown and paying a fair amount for admission to a club and their drinks besides, they weren't going to stand for a tinny-sounding record player. If a speakeasy really wanted to succeed, it needed live musicians. Some of the greatest joints of the era, like Harlem's Cotton Club, employed giants of the music world like Duke Ellington. His orchestra scored a serious win when it became the Cotton Club's house band in 1927, according to Britannica.

Genders mingled like never before

Before Prohibition became the law of the land, women already had a complicated relationship with the concept of drinking in public. Women were generally expected to keep their alcohol consumption private, and certainly a "lady" would never be seen in a down and dirty saloon with the common drunks. But, as Vice reports, many people who broke the law established by the Volstead Act assumed that, if they were in for a penny, they might as well be in for a pound, socially speaking. For young women, it was also an opportunity to mingle with men like never before, and without the troublesome presence of chaperones or nosy church ladies. Thus, the racy, individualized practice of "dating" became popular.

To help encourage this increasingly gender diverse clientele, speakeasies might change how they did business. As per "Last Call," a few places added table service, allowing women to skip the step of bellying up to the bar to order a drink. This more discreet way of ordering was considered more accessible to women who might still be shy about public drinking. And rather than expect women to just sit around drinking, speakeasy managers began to expand their entertainment options, adding live music and dance floors to make it a real party.

With the combined powers of a decent drink, good music, and an energetic dance like the Charleston, many women found it easier than ever to enter the speakeasy and be as daring as they pleased.

A newfangled cocktail might kill you

Technically speaking, cocktails have been around since long before Prohibition. According to VinePair, these mixed drinks arguably got their start as punches, served in big bowls containing liquor and mixers, sometimes served up in appropriately-named "punch houses."

VinePair argues that Prohibition naturally hurt American bar culture, and that it was really World War II and the postwar period that saw professional bartenders returning to American shores. However, Smithsonian Magazine makes the case that cocktails really got a bit of a kickstart from Prohibition. But imbibers who downed one during the less-than-legal days of drinking in the United States needed to be cautious. All of the alcohol being consumed was, naturally enough, unregulated. Some of it could come from seriously funky sources, from a backwoods still to a neighbor's vaguely-washed bathtub.

Bootleggers even sometimes used industrial alcohol, which had been loaded up with nasty-tasting adulterants to discourage illicit use. Their attempts to make that alcohol palatable were uneven at best. Unscrupulous producers reportedly added toxic ingredients to mimic genuine flavors, like rotten meat to make "bourbon" or antiseptics to produce "Scotch." Especially unlucky speakeasy patrons might end up drinking embalming fluid, according to "Last Call."

To mask the taste of less-than-ideal booze, many bartenders used mixers like juice or honey. Unlucky drinkers still faced serious consequences. Some might endure frightening hallucinations, others would become dangerously ill, and a significant number of Americans died from tainted drinks (via Slate).

Snacks were a big deal in the speakeasy

Anyone who's gotten to a certain uninhibited state after a convivial night of drinking knows that, sooner or later, the munchies are going to hit. Maybe someone suggests a pizza delivery, or an enterprising soul might start rifling through the fridge or pantry in search of the perfect snack to accompany that next round of drinks. Consider also the popularity of snack menus and food trucks at local breweries. Things weren't all that different for people visiting speakeasies.

This wasn't exactly the era of greasy late night chow, though, and not exactly because getting pizza sauce stains out of an evening gown is a real task. Instead it was all about the little bites. According to PBS, canapes were already a popular party food before Prohibition, first debuting in 18th century France. They were beautifully suited to parties, with their small size and ability to be eaten without the fuss of utensils or other tableware.

These snacks became especially useful in loud, crowded speakeasies. Not only were they easy to handle while drinking and socializing, but they also gave people something to have in their stomachs. That kept patrons from getting blotto right away and also hopefully helped them stay sober enough on the way home that they didn't attract police attention for public drunkenness. If not, there was always the chance that a sufficiently motivated cop might retrace the drunk's steps and uncover the speakeasy from which they emerged.

A speakeasy might be an LGBTQ-friendly place

Though entering a speakeasy was no guarantee that everyone inside would be a champion of the dispossessed, people had a far better chance at meeting some form of acceptance inside than out. To that end, Prohibition-era speakeasies could host LGBTQ guests and performers with far more frequency than the rest of the world was willing to accept.

According to History, gay culture enjoyed a new era of openness during the 1920s. Drag balls, in which attendees thumbed their noses at gender norms while strutting their stuff in glamorous gowns, had already been a fixture of metropolitan nightlife in places like New York City. By Prohibition, thousands of people took part. It was such a force in speakeasy culture of the time that people dubbed the proliferation of drag performers and LGBTQ-friendly spots the "Pansy Craze," as per Vice. Though members of the community would have to endure a cultural backlash in future decades, the more open world of the speakeasies set the stage for gay culture of the future.

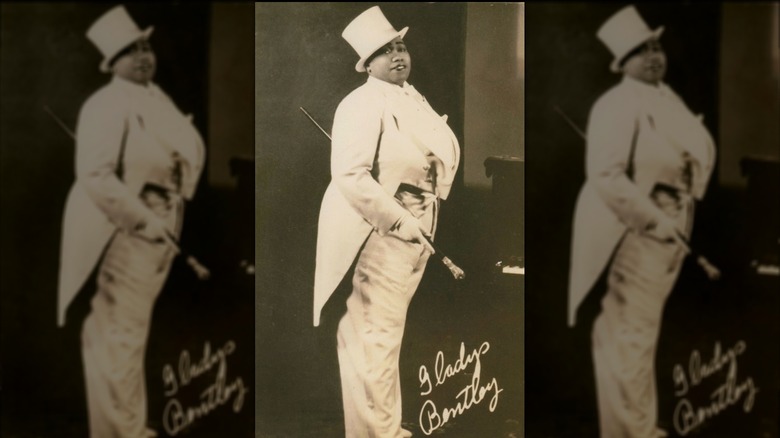

There were even dedicated LGBTQ speakeasies. Visitors to Harry Hansberry's Clam House in New York, one the best-known underground spots catering to gay clientele, might even have seen legendary blues singer Gladys Bentley performing on stage (via Smithsonian). Bentley, an icon of the Harlem Renaissance and member of the LGBTQ community (at least until McCarthyism got to her, as per Smithsonian Music), often dressed in a stylish, traditionally masculine suit and top hat.

Partiers might cross paths with mobsters

People in a speakeasy might have liked to pretend that things were all fun and games — easy enough to do when you're already extra giggly due to the free-flowing alcohol — but the harsh reality of Prohibition still sometimes reared its head. Few people personified the ugly side of going to a speakeasy than the figure of the mobster. For the truth was that at least some of the speakeasies were established after violent turf wars between gangs and shootouts that involved criminals and police officers.

As The Guardian notes, speakeasies were part of a poorly regulated and often lawless landscape that was inadvertently encouraged by small-government politicians. People as high-up as the president were reluctant to interfere with local decisions, even though the Volstead Act was nationwide legislation. Into the power vacuum stepped organized crime, seizing the opportunity to make money in sometimes bloody fashion. Bootlegging and speakeasies were just too good for gangsters to pass up, even rivalries between gangs led to turf wars like the Saint Valentine's Day Massacre in 1929 (via History).

According to History, speakeasy patrons might first encounter low-level gangsters providing security on the premises. They might also be the ones doing the heavy lifting by transporting illegal alcohol to speakeasies. Or, if someone was especially unlucky or daring, they might run across notorious mob boss Al Capone, at least when he wasn't ordering bloody gangland massacres or being arrested for tax evasion in 1931.

A raid might happen at any point

Though many bars paid police to look the other way, that didn't mean a raid was impossible. The sudden appearance of the vice squad might cause people to scatter. Of course, that may have been part of the appeal of the speakeasy, at least for some patrons who enjoyed the thrill of drinking their tipple when it could all come crashing spectacularly down in a moment.

That frisson of excitement that might come about during a raid could be tempered by the realization that consequences for drinkers were rarely dire. Certainly, they were pretty tame compared to what was faced by operators who were caught red-handed. After all, the Volstead Act specifically forbade the production and distribution of alcohol, but not explicitly its consumption (via National Archives). To that end, the real fear and excitement might have come from behind the bar as word of approaching police made its way through the speakeasy.

According to "Last Call," even the fanciest establishments that presumably had a considerable bribery line item in the budget had to plan for a raid. The bartender at the ritzy 21 Club in Manhattan was, with warning from the doorman, able to push a button that immediately dumped all of the bar's liquor down a bottle-smashing shaft. Grates allowed the alcohol to drain away before the police found the shattered remnants in a basement level.