Chilling Details About The Father Of Gynecology

A great deal of medical knowledge has historically been amassed through the exploitation of vulnerable people. American doctors learned about STDs through experimenting on imprisoned people and people in psychiatric hospitals in Guatemala and Swedish dentists learned about tooth decay by experimenting on people with intellectual and developmental disabilities at the Vipeholm Mental Institution.

During the period of enslavement in the United States, this was no different, and doctors frequently used enslaved people for their human experimentation. This was largely the case in the field of gynecology, especially after the transatlantic trade of enslaved people ended.

As a result, one man has gone down in history as the Father of Gynecology for the tools and surgical procedures he invented, but these inventions were all at the expense of enslaved Black women, who couldn't consent to or refuse his forced experimentation. And because enslaved people had few options for medical care available, they were often forced to succumb to the forced experimentation. These are some chilling details about the "Father of Gynecology."

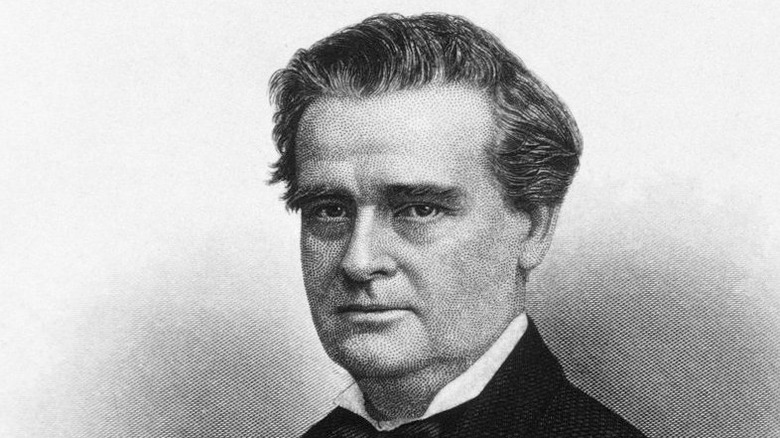

Who was J. Marion Sims?

James Marion Sims was born near Lancaster Country, South Carolina on January 25, 1813. Initially, Sims' only interest in a medical career came mostly out of the fact that he wanted to marry Eliza Theresa Jones, the daughter of the only doctor in Lancaster County. But after getting his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College in 1835, it would take less than 20 years for Sims to make a name for himself in the field of gynecological medicine, writes The Embryo Project Encyclopedia.

Initially, Sims opened a medical practice in Lancaster, South Carolina, but after two infants died during his treatment within the first year, his practice failed and he moved to the frontier region of Alabama and started treating enslaved people, according to the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

After building a private eight-bed hospital in the back of his home, Sims started making a living as a doctor for enslaved people on local plantations, and the Journal of the National Medical Association writes that initially, Sims operated on enslaved Black people without showing any interest in gynecology.

Experimenting on enslaved people

At his clinic, Sims used enslaved Black people both as workers and for human experimentation. Tragically, few survived the experimentation. According to "Medical Apartheid" by Harriet A. Washington, at least four enslaved people died after being surgically operated on by Sims, including one 19-year-old enslaved person who had bone segments removed without any anesthetic.

Another enslaved person almost suffocated after Sims left a sponge from his mouth after removing part of his cancerous jaw, while another almost bled to death after Sims failed to staunch the bleeding from the carotid artery. Sims also reportedly glossed over the details of his mistakes or patients' deaths upon writing up the case studies and instead "dwelled[ed] upon technical details of greater interest to his medical readers."

In "When Doctors Kill," Joshua A. Perper and Stephen J. Cina write that Sims also experimented on infants born to enslaved Black mothers. Sims believed that the movement of the skull bones during birth led to lockjaw, which is now known to be an early symptom of neonatal tetanus. Hampton University writes that Sims attempted to remedy the lockjaw suffered by infants by "pry[ing] the bones of their skulls into proper alignment" with a shoemaker's awl.

This attempt was based on the myth that "the bones of black infants' skulls, unlike white infants', grew together quickly, leaving the brain no space to grow or develop." And when the babies died as a result, Sims would blame their Black mothers and the Black midwives.

Disinterest his own field

Despite the fact that Sims went on to become known as the Father of Gynecology, his disgust towards internal genitalia is surprisingly well-documented. Before his focus shifted onto gynecology, Sims is quoted as saying "If there was anything I hated, it was investigating the organs of the female pelvis," according to the Journal of the National Medical Association,

Sims's work in gynecology ended up being largely accidental. In his own autobiography, Sims would later write that in his treatment of enslaved people "I never pretended to treat any of the diseases of women and if any women came to consult me on account of any functional derangement of the uterine system, I immediately replied, this is out of my line," per the Journal of Medical Ethics.

However, everything changed in 1845, when Sims was called to treat a white woman who was suffering from a "dislocated uterus" after falling off a horse. According to The Atlantic, it was during this examination that Sims created the first speculum using the bent handle of a silver gravy spoon. With this, Sims realized that he could potentially try treating vesico-vaginal fistulas, since now with the use of the speculum he'd be able to see them.

Lucy's operation

Sims's first vesico-vaginal fistula operation was on an enslaved woman named Lucy shortly after he created the first speculum. According to Women & The American Story, Sims reportedly invited other doctors to watch the operation and the operating room was packed with twelve other doctors, despite the fact that Lucy wasn't asked whether or not she'd be comfortable with an audience. Lucy was brought into the room naked and positioned on her hands and knees. She was also restrained during the operation, which was done without any anesthesia. Later in his memoirs, Sims would write that through the use of the speculum, "I saw everything as no man had ever seen before," per Harper's Magazine.

According to the Journal of Medical Ethics, the operation lasted one hour and although the larger fistula was repaired, two fistula remained. Because Sims used a sponge to drain urine away from her bladder, Lucy became sick with blood-poisoning and almost died after the operation. It ended up taking Lucy almost three months to completely recover. The Conversation writes that Sims himself acknowledged that the use of the sponge was "a very stupid thing for me to do."

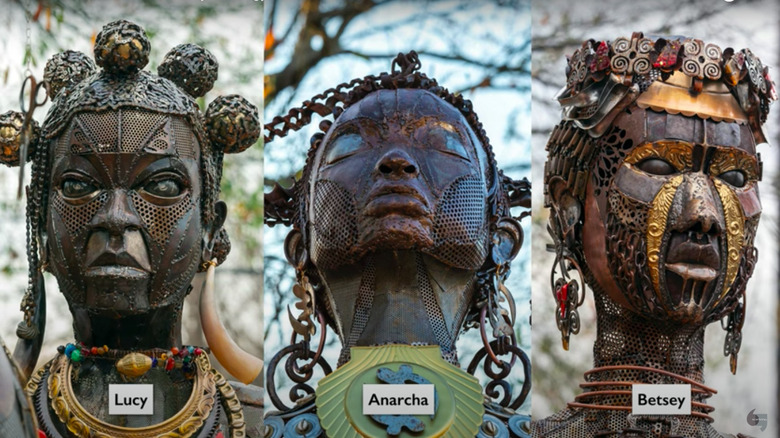

Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey

Although Sims experimented on upwards of twelve different enslaved Black women, the ones that are known by name, because they were named in his published reports, were Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey. According to the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lucy was 18 years old at the time, Bersey was 17 or 18, and Anarcha was 17 years old. These twelve enslaved women were experimented on by Sims for almost five years. Anarcha alone was operated on up to 30 times.

In 1949, Sims reportedly perfected his technique and Anarcha's largest fistula reportedly healed after the 30th operation in the summer of 1849. The Conversation writes that Sims' use of silver sutures would finally cut down on the spread of infections. Afterwards, Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey were all returned to their enslavers.

According to "Medical Apartheid," Sims did start administering pain medicine at one point, but did so in a way to control the enslaved women rather than actually relieve their pain. He would administer morphine to them after the procedure, not during, as a way to ease the recovery. The fact that Sims didn't give them any during the procedure itself reportedly confused some of Sims contemporaries. "The most logical explanation is that this practice had more to do with controlling the women's behavior than controlling their pain, because the addiction weakened their will to resist repeated procedures," according to Washington.

No anesthesia

When experimenting on enslaved Black women, Sims never used any form of anesthesia, which meant that they were conscious throughout every fistula operation. While some accounts write that the lack of anesthesia was due to the fact that doctors feared that people might die from it, this claim seems less credible when one considers that Sims later started anesthesia for fistula surgeries for white women, because "none of them, due to the pain, were able to endure a single operation," according to the Journal of Medical Ethics.

In addition, "Medical Apartheid" confirms that in the 1860s, Sims had no qualms about administering ether to white women, who suffered from vaginismus, which made it impossible to have sex, in order to "rende[r] them unconscious so that their husbands could have sex with them."

The operations were reportedly so painful for the dozen enslaved Black women that the doctors who initially assisted Sims with the surgeries ended up leaving within a year, unable to bear "the bone-chilling shrieks of the women." As a result, the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology writes that the enslaved women subjected to the surgeries also ended up being trained as surgical nurses as they were forced to assist with the operations as well.

Myth of different pain thresholds

The use of anesthesia for white women but not for Black women can also be attributed to the racist myths about different pain thresholds. Dr. Thomas Hamilton was one of the early proponents of this myth and in the 1820s and 1830s, he experimented on enslaved people to try to prove that there are physiological differences between Black people and white people. The New York Times writes that after subjecting enslaved people to horrifically abusive experiments, Hamilton claimed that the bodies of Black people functioned differently than the bodies of white people.

The idea that Black people had a higher pain threshold than white people was one of the myths that was taken up by the scientific community and ultimately used as justification for Sims' experiments. In "Medical Apartheid," Washington writes that Sims also claimed that his procedures were "not painful enough to justify the trouble and risk attending the administration" and later claimed that Lucy had "bore the operation with great heroism and bravery," despite noting later that her "agony was extreme."

But according to the Journal of Medical Ethics, Sims's experiments may have gone too far even for his contemporaries. During his experiments, "dark rumors [began to circulate around town] that it was a terrible thing for Sims to be allowed to keep on using human beings as experimental animals for his unproved theories." And according to UVA, these myths about the pain tolerance of Black people persist in the 21st century.

Hiding the nature of his experiments

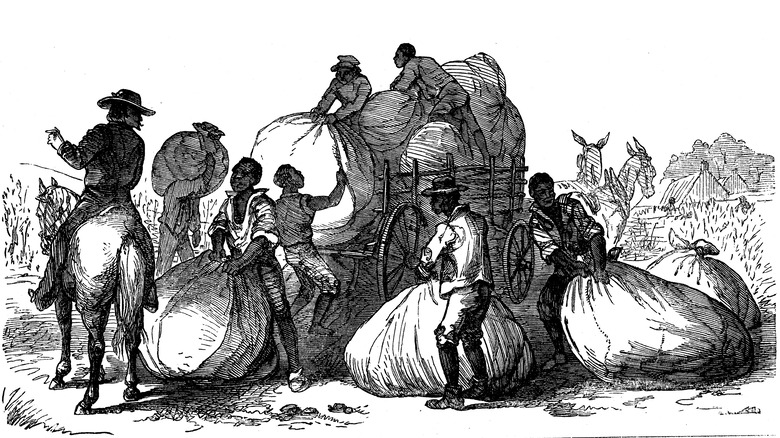

Although Sims spent almost five years experimenting on enslaved Black women, he was less than forthcoming about these experiments when he finally published his findings. According to "Medical Apartheid," while Sims lived in Alabama and the South, he defended the system of enslavement and frequently used slurs in his writings. But once he moved up north to New York City, he started lying about the ethnicity of his experimental patients and in the illustrations accompanying his reports, the women were depicted as white. As an additional insult to injury, the illustrated women are covered and allowed a sense of privacy that neither Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey, nor the other enslaved women were afforded.

Sims also praised the courage of these women in his accounts without mentioning that "it was chattel slavery and morphine, not courage, that had bound the women to his surgical table."

Women & The American Story also notes that in his 1852 article that outlined the surgical procedure for treating fistulas, Sims never even mentions that the women he was operating on were enslaved. "He also never mentioned that the enslaved women became skilled medical practitioners."

Did his surgeries work?

Although Sims raved that his surgeries were a phenomenal success, it's questionable whether or not his surgeries actually offered long-term results for the enslaved Black women he operated on. The Journal of the National Medical Association writes that Sims claimed that "all of the slave-women who had been the subjects of his experiments were cured and sent home," but even some of his colleagues who worked with him had drastically different versions of events.

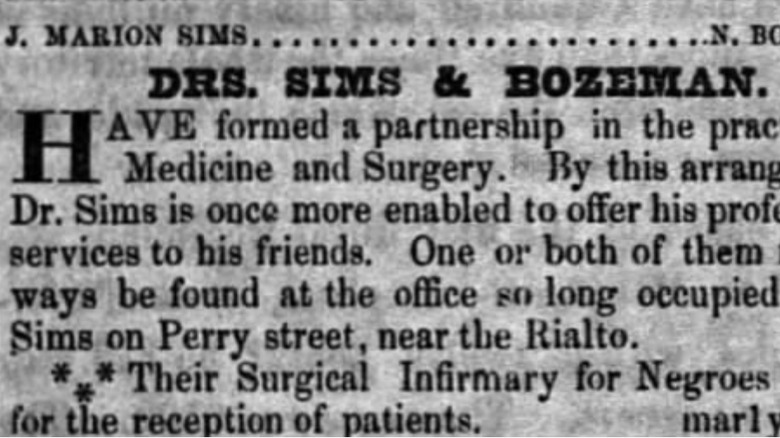

According to "Medical Apartheid," Sims's colleague Nathan Bozeman insisted that less than half of the enslaved women they experimented on received any sort of long-term relief. "Bozeman even described a case of vesico-vaginal fistula created by Sims when he removed the bladder stones of a nine-year-old slave girl."

After Sims abandoned his practice in the South and moved north, Bozeman even reported fixing some of the fistulas himself using button sutures, a technique that Bozeman had also perfected by experimenting on enslaved Black women.

A Confederate agent

After the Civil War began in 1861, Sims moved to Europe and stayed there for the duration of the war, returning in 1868. However, although Sims' travels have been attributed to his medical practice or for his own health, per "Human Medical Experimentation," there's evidence to suggest that Sims was actually in Europe as a Confederate agent. According to the Montgomery Advisor, during his travels, Sims was already on the radar of Henry Shelton Sanford, known as Lincoln's Spymaster, who was responsible for coordinating the early surveillance of Confederate agents in Europe. In one incident, there's even evidence to suggest that Sims was responsible for stealing an official passport seal in Belgium. Meanwhile, there's little writing about Sims' time in Belgium, other than the fact that he performed "three surgeries in a single morning, and though one of his patients died, a banquet was thrown in his honor."

After Sims was called to act as a physician for Empress Eugenie, the wife of Emperor Napoleon III, she was described as becoming an "ardent apostle" for the Confederacy. While France never joined the American Civil War, Napoleon III did give permission for Confederate ships to dock at Brest and Cherbourg after meeting Sims. Although Empress Eugenie is one of the most famous of Sims' patients, "it was never revealed what Eugenie's condition was, and given the context it seems possible that Napoleon needed Sims for clandestine communication with the South."

Leaving his own hospital

In 1868, Sims returned to the United States and settled in New York. There, he resumed working as a gynecologist at the Women's hospital that he'd founded in 1855, reports The Atlantic, and became surgeon-in-chief in 1870. However, according to "The Empty Cradle" by Margaret S. Marsh and Wanda Ronner, Sims was soon quarreling with the other doctors over both medical decisions as well as policy decisions.

Robert F. Zacharin writes in "Obstetric Fistula" that the Board of Governors made a decision in 1871 that Sims was reportedly opposed to. The first decision was that no people with carcinoma uteri should be admitted into the hospital, because it was believed that cancer patients were contagious. The second decision involved the fact that no more than 15 people were now to be allowed to be present at vaginal operations, instituted for the sake of modesty.

In response to these two new regulations, Sims reportedly gave a "fiery speech reflecting severely upon the tyrannical course of the Board," stating that he refused to follow those rules and threatening to resign. To his surprise, his resignation was accepted by the board and Sims was forced to resign from the hospital he founded less than 20 years earlier.

Experimentation was the standard of care

While the story of what happened to Lucy, Anarcha, Betsey, and the other enslaved Black people experimented on by Sims is horrific, at the time forced experimentation was the only standard of care afforded to enslaved people, especially in the realm of gynecology. According to "Medical Apartheid," the method of cesarean sections was perfected by a Louisiana surgeon named Dr. François Marie Prévost after experimenting on numerous enslaved Black women. Dr. Ephraim McDowell, a contemporary of Prévost who was the first person to perform a successful ovariotomy, also experimented on several enslaved Black women before this surgery was perfected. Virginia's Dr. P.C. Spencer is also known for inventing a surgical procedure for bladder stones that was created after surgically experimenting on enslaved people.

The Washington Post notes that not only was the entire American medical system created through the exploitation of enslaved Black people, but this racist history can still be seen in the 21st century in how Black patients are treated by doctors. This is especially true of the field of gynecology, since after the federal ban on importing enslaved people in 1808, the economic incentives behind promoting the births of health enslaved children pushed medical innovation.