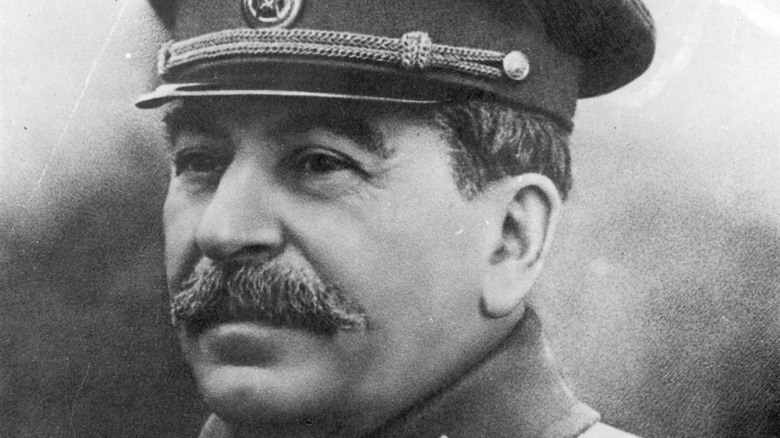

Here's How Joseph Stalin's Cannibal Island Was Discovered By The Public

From the 1920s to the 1950s, the Soviet Union operated hundreds of forced labor camps where, overall, 18 million people were imprisoned, according to History. The conditions in Joseph Stalin's gulags were horrific. One to two million people died of overwork, starvation, the elements, disease, or execution (via Britannica). The camps were full of dissidents, persecuted ethnic groups, Stalin's political enemies and anyone connected to them, common criminals, and more. The labor was a key part of the Soviet Union's rapid industrialization; Stalin wanted the nation modernized, so prisoners worked on massive infrastructure, mining, and industrial projects.

In the early 1930s, Soviet leadership envisioned a different sort of labor camp. It was decided that two million citizens would be rounded up and transported to Siberia and Kazakhstan, where they would build new communities and engage in agriculture (via Radio Free Europe). They would have no choice in these remote areas but to become self-sufficient and plant for survival, which would help fight the nation's famine. One such place was Nazinksy (or Nazino) Island, a tiny spot of land in the middle of the Orb River, which was in the center of Russia's colossal landmass. It would soon be known as Cannibal Island.

The Island of Death

In 1933, Soviet soldiers shipped over 6,000 people to Cannibal Island (also named the Island of Death). According to Atlas Obscura, the prisoners were given no tools, shelter, extra clothing, or food, save some flour that could not be cooked without proper utensils and thus had to be eaten as it was or mixed with river water, causing dysentery. Hundreds died the first night. Guards shot anyone who attempted to cross the Orb River for the other shore (via Radio Free Europe). There was violence over any meager resource. Starving, the captives quickly began killing and eating each other. Some were killed and devoured — others had body parts sliced off and were left to attempt to survive.

"I saw that her calves had been cut off," a resident of a nearby town, who later met a former Cannibal Island prisoner, remembered. "I asked and she said, 'They did that to me on the Island of Death — cut them off and cooked them'" (via Radio Free Europe). Prisoners seized another girl, a witness recalled, "tied her to a poplar tree, cut off her breasts, her muscles, everything they could eat, everything, everything ... They were hungry ... They had to eat" (via History Collection). The guards did little to stop the horrors.

After a month or two, over 4,000 people had died from violence, disease, and the cold, and the Soviet government ended the social engineering experiment on Nazinsky Island, shipping the frail survivors elsewhere. Though the survivors and residents of nearby villages knew what happened during those bloody months, as did Stalin and the U.S.S.R. leadership, the wider public of Russia and the world would have to wait half a century to hear the tale.

The Secret Comes to Light

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev enacted a policy of glasnost, or openness, as the nation began to democratize. Government secrets, the terrors under Stalin, suppressed information — they slowly came to light and could be discussed more openly (via Britannica). In July 1933, a communist instructor named Vasily Velichko had been living near Nazinsky Island and, hearing the whispers of cannibalism, investigated for himself, according to Radio Free Europe. He sent a report to Moscow documenting the events, which was buried until 1994. Other reports, such as those generated by the government's investigation spurred by Velichko's writing, likewise did not stay hidden forever.

It is also thanks to the efforts of the Memorial human rights group that this history has been preserved. In 1989, the group went to Nazinsky and nearby areas to speak to survivors, witnesses, and others, collecting oral histories (via Radio Free Europe). Today, a leading text that educates the global public on this topic is historian Nicholas Werth's "Cannibal Island: Death in a Siberian Gulag" from 2007.