The History Of Eating Poison On Purpose Explained

In the 1987 film "The Princess Bride," charming Westley vanquishes the irritating Vizzini in a battle of wits involving a small vial of iocaine poison and a bottle of wine. Vizzini agrees to undertake this challenge despite knowing that winning means his opponent would have to nobly and willingly drink a cup of poisoned wine, but somehow it never occurs to him that maybe he's being tricked. Never mind, because the audience is already painfully aware that Vizzini isn't as smart as he thinks he is.

Anyway, Vizzini dies and Buttercup declares, "To think, all that time it was your cup that was poisoned!" and then we learn that Westley did a mithridatism thing and off they go to the Fire Swamp.

Wait, mithridatism? Yes, there is a medical term for how Westley survived the battle of wits — in fact, the practice of taking sub-lethal amounts of poison in order to build immunity dates all the way back to 120 B.C. and a Pontic king named Mithridates. Over the years, mithridatism has found its way into various legends and stories until it finally became a movie trope round about the time of "The Princess Bride." But is there any truth to it? Is it possible to eat poison in order to become immune to eating poison? Yes! Well, yes and no. Here's the bizarre and semi-scientific history of eating poison on purpose.

Mithridates was terrified of being poisoned, so he ate poison

In 120 B.C., Mithridates lost his father to (you guessed it) poison. So began a lifelong obsession that was part scientific inquiry and part hyper-paranoia. Mithridates was so sure people were trying to kill him, he even suspected his own mother of being in on an assassination plot (via "History of Toxicology and Environmental Health"), which — given how royalty was in those days — was probably not that far off base.

Mithridates divided his time between doing kingly things like strumming a hurdy-gurdy and eating whole roasted boars (just kidding, those were medieval things) and studying toxic substances. In fact, he even wrote a book on toxicology, and besides being the guy who popularized the poison-survival technique that would later save Buttercup's true love from certain death, he was also one of the world's first toxicologists. The anti-poison formula he regularly consumed was said to include small amounts of local toxins, including hemlock and snake venom. It also contained some healthy stuff like parsley and carrots, you know, because you should always eat your veggies while you're deliberately poisoning yourself.

It's hard to draw any firm conclusions based on 2,000-year-old-plus historical records, but Mithridates' contemporaries say his concoction worked. In fact, the king would sometimes show off to his friends by swallowing poison on purpose and not dying (via the World History Encyclopedia). Hey, cut the dude some slack, it's not like they had TikTok in those days.

Mithridates died the most ironic death of all time

Mithridates' poison obsession immortalized him through the ages, but if you look at all of the most memorable things about his life, his poison obsession is kind of neck-in-neck with the circumstances of his death. If the story is true, anyway. According to researcher Jakob Munk Hojte, there is more than one story about how Mithridates died — in the most boring of the two, he was murdered by traitorous troops during a rebellion. In the more popular story, after he learned of his defeat, he decided to end his own life by ... wait for it ... taking poison. Predictably, the time he spent during his life building up an immunity to poison foiled his self-poisoning attempt and he had to ask one of his bodyguards to kill him with a sword instead.

It's a great irony, but certain historians doubt the authenticity of the story. The World History Encyclopedia, for example, wonders if the whole "I eat poison" thing was just a ruse to stop Mithridates' enemies from trying to poison him. It would've been easy enough for him to pretend like was publicly eating poison because it's not like anyone else was going to eat the stuff to prove him wrong. The author also doubts the details of the more popular story of Mithridates' death, pointing out rather reasonably that Mithridates was also helping his two daughters take their own lives as well and likely had to split a single dose of poison three ways, which probably meant he didn't ingest a lethal amount.

After his death, Mithridates' formula was a hot ticket

Whether or not Mithridates really did possess an elixir that could protect him from all known poisons doesn't really matter — it was the idea. After his death, the supposed elixir apparently became so powerful that kings, queens, alchemists, priests, and random other people all claimed to possess the recipe, though it's unclear if any of them really did. It doesn't really matter, though, because it was probably enough to just say you had the formula — that by itself would be enough to deter people from trying to poison you.

According to "History of Toxicology and Environmental Health," after Mithridates' death, more than one Roman physician immediately jumped on the "I have Mithridates' formula" bandwagon, knowing how valuable that might make them to the emperor since emperors and their ilk are always fussing about the possibility of being poisoned. In fact, 700 years later, the emperor of China was given a mithridatium theriac by Islamic ambassadors, and throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, European kings and queens, including Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, are said to have regularly taken mithridatium to ward off assassination attempts.

It's probable that none of these formulas were precise copies of the one Mithridates used (if he used one at all), but the lure of becoming invulnerable was enough to make mithridatium outlive almost every other historical medicine. In fact, Adrienne Mayor, a contributor to Philip Wexler's "History of Toxicology and Environmental Health," calls mithridatium "the most popular and longest-lived prescription in history."

You can't do this with every poison

Over time, Mithridates' formula (or what everyone claimed was Mithridates' formula) evolved into a cure-all for every known poison (via Vesalius). Those who said they knew the secret formula perfected it by adding things like snake meat, opium, animal blood, herbs and minerals, random other poisons, and honey, presumably to make it all go down a little easier.

It's pretty remarkable that the stuff remained in use for as long as it did, actually, because today we know there's no such thing as an antidote to every poison. In fact, some poisons don't have any antidote at all — strychnine, for example (via the CDC) and also ricin (also via the CDC), as poor Lydia found out the hard way.

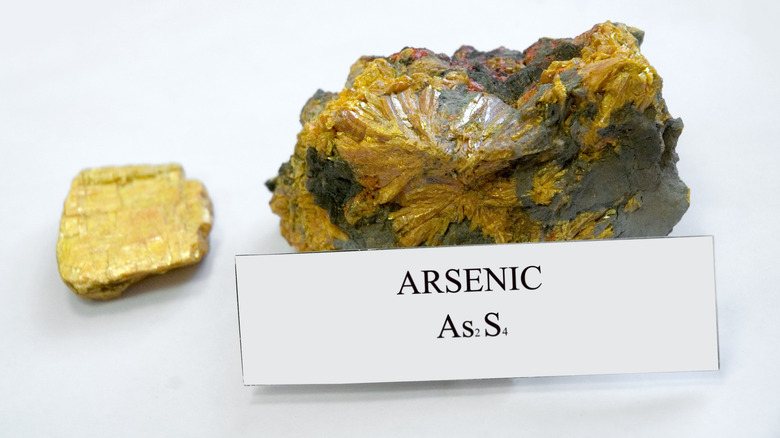

Similarly, professor of medicine Hayk Arakelyan says you can only use the concept of mithridatism to become immune to certain types of poison, namely those that are biologically complex like animal venom or toxic plant compounds. That's because the immune system doesn't respond to certain toxins, especially heavy metals like arsenic.

In fact, according to The Guardian, arsenic may bind to sulfur-containing enzymes in your body, which can cause long-term symptoms like high blood pressure and chronic pain. So not only do those small doses do nothing to move your immune system into providing you with superhuman immunity, but they also cause gradual damage to your body that will make your life very unpleasant until you finally, mercifully, shuffle off this mortal coil.

The toxic substance damsels

Wouldn't it be cool if you could not only be immune to poison but also be poison? Well, according to a paper published by the International Research Journal of Commerce, Arts, and Science, the Vishkanyas of India (literally "poison damsels" or "poison maidens") were exactly that: deadly female assassins, kind of like Villanelle except instead of poisoning their victims with perfume, they used their own poisonous auras. Or something, as the history is not super clear on how exactly that worked. The gist of it is that the Vishkanyas were taken from their families as girls and regularly given sub-lethal doses of poison as they grew. By the time they became adults, they were not only immune to poison but also had poisonous blood and evidently also poisonous other-body fluids, because one of the ways they assassinated their enemies was by seducing them.

The Vishkanyas might have just been a story, in fact in some tellings, they have golden eyes like snakes and skin covered with tiny green scales. On the other hand, Vishkanyas are also mentioned in some pretty official documents, like the Arthashastra (which is otherwise mostly about boring government stuff), as professional assassins employed by emperors. If they did exist, it seems unlikely that they really did have poisonous blood or bodily fluids, but it is possible that mithridatism made them so immune to poison that they could apply it to their nethers and thus slaughter an unsuspecting suitor.

Certain animals were practicing mithridatism long before Mithridates

Some animals produce poisons in their bodies in order to defend themselves from predation. It's a clever evolutionary strategy that increases the chances of survival for the entire species. Sometimes, though, the poison strategy doesn't work exactly like it's supposed to. Certain predators are immune to their prey's natural poisons; others take it one step beyond that.

According to National Geographic, tiger keelback snakes use poison to defend themselves from predators, but they don't make that poison in their own bodies. Instead, they get it from poisonous toads. Not only are young snakes born immune to the bufadienolides that the toads produce for self-defense, but they're also able to store it in glands on the backs of their necks and then present it to whatever unfortunate animal tries to threaten them. Some snake moms even pass the poison on to their offspring, thus giving them a head start as genuine Vishkanyas.

This isn't like a one-off, either. Other animals, including some known in Mithridates' time, do the same basic thing. The ducks that lived in Mithridates' kingdom, for example, ate poisonous plants and had poisonous flesh, and the bees pollinated so many poisonous flowers that their honey contained a deadly neurotoxin (via Toxicology in Antiquity). It's even possible Mithridates' observations of these animals may have been the inspiration for the whole bizarre poison-eating notion.

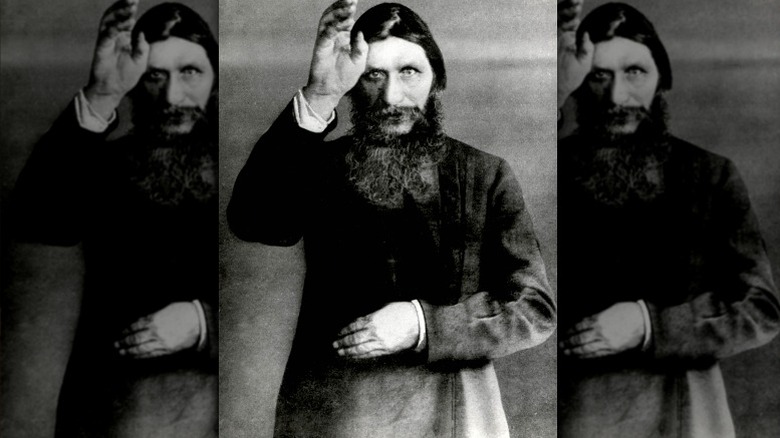

Mithridatium might have saved Rasputin, at least temporarily

Grigori Rasputin (also known as "the mad monk of Russia") is mostly known for being a whack-job and for surviving like 5 million assassination attempts in a single night. He was pals with the Russian royal family, who employed him as a healer. Sounds benign, but Rasputin was also widely disliked because a lot of people thought he was a little too cozy with the Russian royals, especially given that he was also drunk all the time and had numerous affairs with women from all walks of life (via Smithsonian).

According to The Guardian, Rasputin's end came when he was invited to a fake party at the Yusupov Palace in St. Petersburg, where he was fed cyanide-laced cake. But despite the fact that the cakes supposedly contained enough cyanide to take down dozens of people, Rasputin gobbled them up like free samples at a bake-off. His would-be assassins tried giving him wine in a cyanide-laced glass, but that didn't work either. After it became clear that poison wasn't going to kill the mad monk, the assassins shot him (which just made him mad), then shot him again and threw him into a frozen river.

Adrenaline might have kept him going after the first gunshot, but it remains unclear how Rasputin survived the poisoning. According to one theory, per Clinical Toxicology, he was likely to have known people were out to get him, so he might have started practicing some form of mithridatism after his rise to fame.

Sometimes mithridatism killed innocent bystanders

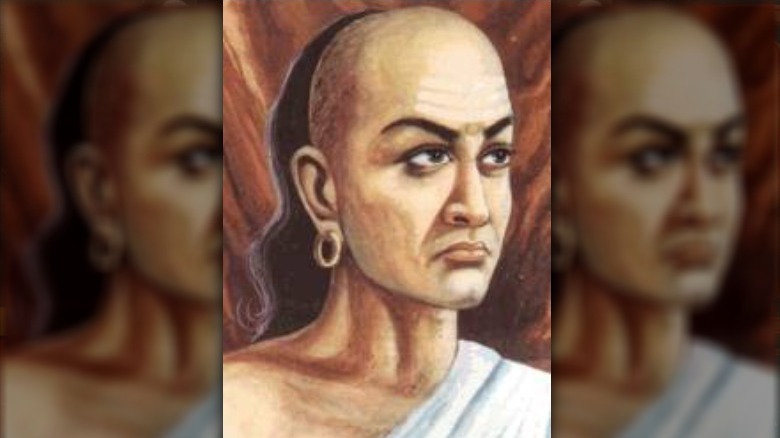

Chnakya was the prime minister of the South Asian emperor Chadragupta. He lived a couple of hundred years before Mithridates, but he had similar ideas about the power of eating poison; in fact, he was so confident in those ideas, he secretly put poison in the emperor's food in order to protect him from assassination. According to researcher Bipin Shah, though, Chnakya failed to consider that sometimes people like to share their food with loved ones, and one night Chandragupta's pregnant queen Durdha tasted some of his poisoned food and died.

Fortunately, Chnakya was a quick-thinking guy. He knew the queen was dead but was determined not to lose the baby, too, so he cut upon Durdha's corpse and saved the emperor's heir. He was quick but not quite quick enough — according to the story, a small amount of poison touched the child's head, leaving a discolored patch. Chnakya named the baby Bindusara, which means "the strength of the drop" (via The Clever Adultress and Other Stories) because for some reason he got to choose the boy's name even though he was responsible for the death of the kid's mother.

Did this really happen? Eh, maybe not. The story is pretty reminiscent of popular fables in the vein of "How the Camel Got His Hump," only in this case, it's "How Bindusara Got His Birthmark." But it might be true that Chnakya was giving Chandragupta small doses of poison to protect him, because poison has always been a popular way to murder a king.

Arsenic is an acne remedy

Just kidding, definitely don't use arsenic as an acne remedy. Accutane and retinol are way more effective and neither one will kill you.

According to The Guardian, there are stories of people in Austria around the mid-19th century using arsenic as a health remedy, sort of like kale only probably better tasting. Proponents said it gave them glossy hair and a lovely complexion, the latter of which might have even been true because arsenic first kills all that awful acne bacteria before it finally gets around to killing you. Unfortunately, it takes time for small doses of arsenic to do you in, and by the time early practitioners started dropping dead, arsenic-eating-for-your-health was already taking Europe by storm.

Not only did the arsenic eaters have flawless skin, but they sometimes also ate large amounts of arsenic in front of an audience in order to demonstrate their remarkable immunity to its poisonous effects. What the audience didn't know was that large chunks of arsenic don't really get broken down in the digestive system, so the demonstrators weren't really immune, they were just eating the poison in a form that was much less toxic than similar amounts of powder would have been.

The arsenic-eating craze didn't last long, fortunately, since arsenic tends to build up in body tissues until it makes you lose your glossy hair and break out in scaly lesions all over your previously flawless skin. Then you die. Stick with the Accutane.

You can, however, be genetically tolerant to arsenic

You don't actually have to eat arsenic yourself in order to develop a tolerance to it. It's actually possible to become tolerant to arsenic because your ancestors ate the poison ... though it's not super clear exactly how many generations have to play arsenic roulette before their heirs will start reaping the genetic benefits.

According to Environmental Health Perspectives, people who are indigenous to parts of the world with a lot of naturally occurring arsenic are naturally resistant to the effects of arsenic. The Atacameño people, for example, live in a small part of Argentina with a long history of mining, which can leave the drinking water contaminated with arsenic. There are even 7,000-year-old Andean mummies that show evidence of arsenic poisoning, so this has been going on for thousands of years.

The Atacameño don't usually die of arsenic poisoning, though, because most of them (around 69%) possess a gene that helps them metabolize the toxin. Researchers think that arsenic may have killed so many of them in the past that natural selection began favoring people with arsenic resistance, sort of like a genetic mithridatism. Unfortunately, the researchers who made this discovery failed to note whether or not the Atacameño also have glossy hair and flawless skin.

You might even practice mithridatism without knowing it

Unless you've never had a drink and you've never taken any medication, you've probably been practicing mithridatism without even knowing it. You know how you used to pass out on the couch after a half glass of wine and now, well, let's just say it costs you a lot more to go to a cocktail party than it used to? That's because over time, you develop a tolerance to alcohol in the same way that Westley developed a tolerance to iocaine poison, only Westley's tolerance let him defeat Vizzini, and your tolerance mostly just lets you defeat your own liver.

Per the Neurobiology of Alcohol Dependence, over time, your body absorbs less of the alcohol you drink and eliminates more of it. But it also has a less robust response to alcohol, which means you have to drink more alcohol to get the same effect. This is really exactly the same thing that happens when you eat poison on purpose (in fact alcohol, though you may love it, is essentially a poison). You're probably also aware, however, that alcohol tolerance isn't exactly a good thing — alcohol tolerance comes with a high price. Those increasing quantities of alcohol will eventually take a toll on your overworked liver, leading to unpleasant conditions like alcoholic fatty liver disease (via Clinical Toxicology).

And yes, it even has applications in modern medicine

No doctor is going to tell you that it's a good idea to take small daily doses of poisonous ricin to protect yourself from would-be assassins and your high school chemistry teacher, but that doesn't mean that mithridatism doesn't have a place in modern medicine. In fact, the principles of mithridatism can be found all across medical practice, from the vaccine you got to protect yourself against COVID-19 to the tablets your doctor gave you to help ward off seasonal allergies.

Vaccines and allergen-specific immunotherapy are both examples of medical practices that are based on mithridatic ideas — a small dose of the toxin/virus/allergen is given in order to help prevent poisoning/illness/allergy in the event of exposure to a larger dose of the toxin/virus/allergen.

With a vaccine, the immune system is given a small amount of a dead or weakened virus or a viral protein so it can learn to recognize and defend against the living virus. With allergen-specific immunotherapy, the allergen is given in very small but increasing doses with the goal of getting the immune system used to the allergen so it doesn't overreact when it meets that allergen in the wild (via Informed Health Online). This form of immunotherapy is even being used to treat people who have severe allergies to things like bee stings or peanuts (via Allergy & Asthma Proceedings), in the hope that it might prevent potentially life-threatening anaphylactic reactions.

Seriously though, don't eat poison oak

Just throwing this one out because it's been making the rumor rounds for a couple of hundred years, though sources seem pretty divided on whether or not it's actually true.

According to California and Western Medicine, for example, indigenous people used to regularly eat the leaves of the poison oak plant in order to develop immunity to the oil that produces an allergic reaction in almost everyone unlucky enough to encounter it. Of course, the journal was published during the first half of the 20th century, when people regularly wrote hearsay down as fact, so take that with a grain of salt.

The idea persists even today, though, and evidently, it is true that certain California natives had some crazy uses for poison oak (via Bay Nature). The Ohlone made baskets out of its stems and ate some form of it with bread. The Karok supposedly used poison oak skewers to cook salmon and even wrapped root vegetables in its leaves for roasting. Whether or not this practice gave them immunity is unclear — Bay Nature also says that many indigenous groups had poison oak remedies, which means at least some of them were subject to the itchy unpleasantness experienced by the rest of us mortals. And let's face it, it does seem kind of possible that maybe the natives were just pranking their interviewers to see if any of them would be dumb enough to try it.

And then there's this guy

Snake venom is one of those biotoxins that it's theoretically possible to develop an immunity to. Snake charmers, at least according to their own reports, practice mithridatism so they can survive their own professions, in fact, Reuters reports that boys are given small doses of snake venom while they're still infants in order to prep them for future snake-handling careers.

This isn't just something that's done in obscure parts of India, either. According to The Guardian, Steve Ludwin does this, too, though his reasons are a lot less clear than the snake charmers' reasons are. Ludwin is a rock musician, so that explains at least part of it. He started injecting himself with snake venom back in 1988 because he was "curious" about the possibility of becoming immune to snake bites. He didn't die, so he just kept on doing it. He even had a close call once, accidentally injecting himself with too much of not one but three different venoms. He didn't die that time, either.

Today, Ludwin is basically a living anti-venom factory. That's not just a metaphor — scientists are actually hoping to use his blood to create the world's first anti-venom derived from human cells. This is a big deal because modern anti-venom comes from horse blood, and some people who receive it develop serum sickness, which is essentially an allergic reaction to non-human proteins in the anti-venom (via Healthline).