What Would Happen If A Former US President Went To Jail?

American political discourse has never been shy about hurling the ugliest and most scandalous accusations possible against ideological rivals. Just take a look at some of the choice expressions deployed throughout history (via Merriam-Webster): "drunken trowser-maker," "pimp of the White House," "b****** brat of a Scotch Pedler." Nor has it been uncommon for whoever holds the office of U.S. president to face accusations of tyranny; George Washington himself faced such claims, a cutting misery for him in his last term, according to American Heritage. But a tangible, criminal charge, the kind of thing that could or should land a man in prison — president or not — is another matter.

Commanders-in-chief have been accused of committing specific crimes, and things have progressed as far as impeachment on four occasions in American history. The only time a sitting president has been arrested, however, is when Ulysses S. Grant was caught speeding in his carriage one too many times (per Business Insider), and that didn't come to more than a $20 fine. But the prospect of a sitting or former president facing criminal charges has become less abstract in recent years, particularly after testimony in the January 6 hearings.

It would mean choppy waters for the United States whether an ex-president was charged or not, and jail time would exacerbate the situation (via The Washington Post). So it's worth wondering: How would a president end up behind bars, and what might happen then?

There's no precedent for it in American history

Just how a president would be convicted and jailed and what such a sentence would mean for the country is a tricky puzzle for historians, legal scholars, and politicians. One reason it's so difficult is that there's no prior instance to look to in American history. No president has faced a court or served time after leaving office. And two past cases that might have been instructive are what-ifs — they never came to trials or incarceration (via Salon).

The first case concerns John Tyler, the 10th U.S. president. Ascending to the office following the death of William Henry Harrison after just 32 days in the White House (per History), Tyler is a little-known but pivotal figure in the history of the presidency. He established that a vice president assumed the full powers of the president if the incumbent died in office, according to Edward P. Crapol's "The Accidental President." But when the Civil War broke out in 1861, Tyler went with Virginia into the Confederate camp and was elected to its Congress. Before the war ended, he died and was thus unavailable to serve as an example of a jailed ex-president guilty of treason.

The other potential guide would have been Jefferson Davis. He claimed an equivalent rank as president of the Confederacy, made it to the war's end, and was set to go to trial. He might even have won it, according to the Smithsonian, but President Andrew Johnson pardoned all the rebel leaders, Davis included.

Other countries have been down this road

If America has no precedent in its history for an ex-president going behind bars, other nations have seen comparable developments in their recent history that might offer an example. Salon recorded several while mulling over Donald Trump's possible future. Italy sent their former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi to prison in 2013 for tax fraud, though he was allowed to spend his sentence doing community service. Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been indicted, though as of July 2022, his trial remains ongoing (per ABC News). And in France, a former prime minister (François Fillon) and a former president (Nicolas Sarkozy, per the BBC) each received a short prison sentence.

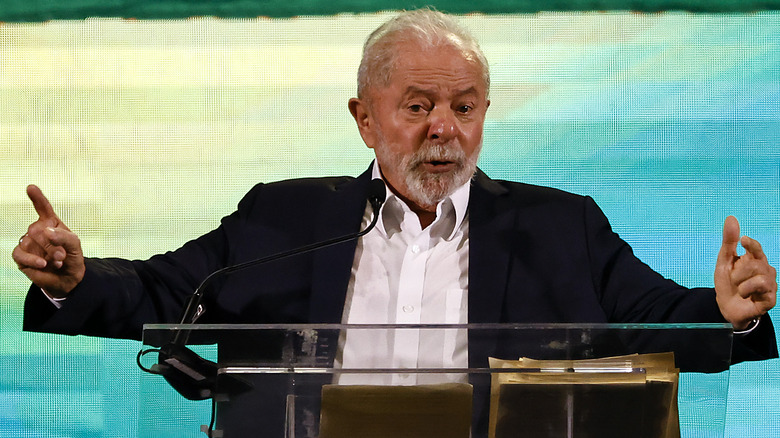

None of these countries have a presidential system of government in the style of the United States (see the World Population Review). But there are presidential republics that have dealt with former chief executives accused of crimes. According to The Washington Post, Argentina's Carlos Menem, Peru's Alberto Fujimori, and Brazil's Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva have all gone behind bars. But if South America's example shows that prosecuting a former president can be done, it also shows the dangers of going down that road. Whether Menem, Fujimori, or Lula committed the crimes they were accused of, their supporters believed them victims of political machinations. The convictions didn't improve national stability and, at least in the short term, helped to exacerbate disunity.

Could any trial be impartially conducted?

Suppose that a former president was credibly accused of crimes and the case came to trial. One would hope that it could be conducted with impartiality. After all, America was famously meant to be a government of laws, not men (per the John Adams Historical Society). But the plain fact is that no prominent figure in government could be tried, even out of office, without the risk of political passions overriding the law.

Such risks have been proven in American history. Aaron Burr is best known for killing Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Before that, however, he was Thomas Jefferson's disliked, distrusted, and duplicitous vice president. After his fateful duel, Burr was left off the Democratic-Republican ticket in 1805 and sought to remake himself out west (per Zocalo Public Square). Just what sort of reinvention Burr planned is unclear; he may have wanted to make money, conquer Mexico, or carve out U.S. territory for his own empire. The latter would constitute treason.

When the allegations reached the White House, Jefferson was convinced of Burr's guilt — so convinced he named him traitor without an arrest, indictment, or trial. He was just as hostile to Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, a political rival. Jefferson attempted to direct the prosecution from the White House and even tried to stack the jury. But hard evidence against Burr was weak, and Marshall ruled that no overt act of treason could be attributed to Burr.

It would be very hard to get to that point

Trials by jury are a difficult business. The accused could be guilty as sin, but unless the evidence against them is solid and presented satisfactorily, they're unlikely to see justice. Should the accused be a one-time president, possessed of great political support and the vestigial glow of respect from the office, any prosecutor's task becomes more difficult. The Atlantic explored all this in the context of Donald Trump's legal woes since his 2020 electoral defeat. Allegations of fraud by Trump in the New York real-estate business may have compelling evidence behind them, but they also represent common practice, a fact that could strengthen a defense built on claims of politically-motivated attacks. And any charges brought against Trump for the January 6 insurrection would have to make an argument that his failure to restrain the mob — in other words, doing nothing — was a crime.

But a hypothetical prosecutor arguing against a hypothetical former president should count themselves lucky that the accused is out of office. Any attempt to bring a case against a sitting president would be further complicated by legal theory. The Department of Justice maintains a policy that federal charges can't be brought against a sitting president. That stance has faced significant criticism from legal scholars, to be sure — Vox collected rebukes from 16 of them. But many presidents have also used the unitary executive theory to defy legal restraints and frustrate investigation (per Bloomberg Law).

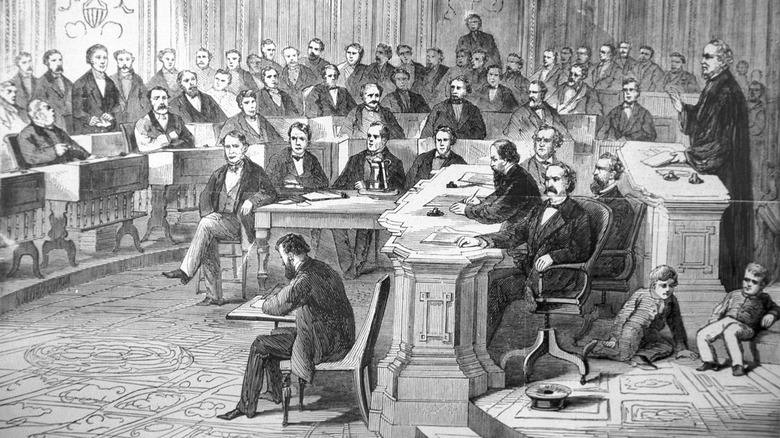

Impeachment ≠ incarceration

If a president ever committed a crime, under the current policy at the Department of Justice, they would have to become a former president to face charges, and removing the president from office would require impeachment. According to the History, Art, & Archives page of the House of Representatives, it is only the House that has the power to impeach a federal official like the president. Should a majority of the House vote to impeach, the trial is conducted by the Senate, with designated managers set by the House to serve as prosecutors. It's a difficult process, complicated by partisanship. Only 20 officials have been impeached in U.S. history, and only eight have been convicted by the Senate, all of them federal judges.

But if a president were ever to be impeached and convicted, why wouldn't that send them to jail? The Constitution limits the power of impeachment to removing federal officials from their posts. The Senate could decide that conviction disqualifies an individual from returning to power, but it has only done so three times. On the other hand, unlike criminal trials, the Senate is allowed to set its own rules, and those rules are subject to change with a majority vote at any time, according to WUSA9. But the fact that impeachment isn't a criminal trial is what lets a president removed by that process face a criminal trial; it would be double jeopardy otherwise.

They would (probably) still get Secret Service protection

Since 1965, the Secret Service has been obliged to protect former presidents and their spouses for life unless the president should refuse protection (per the agency's FAQ page). That is the only qualifier listed. Since no former president has ever gone behind bars, it's never been seen whether they would continue to be protected by the Secret Service while incarcerated. When Slate looked into this in 2018, a spokesman told them: "It's a road we would have to go down if it ever happened. It's not something we're going to think about unless it happens." Unless an act of Congress stripped an incarcerated ex-president of their protection, however, they would likely still get it.

The image of a Secret Service agent, in suit and sunglasses, sitting in a cell with a commander-in-chief turned convict, could make for a good comedy. But in reality, things likely won't come to that. The agency could, after inspecting the facilities, station a protective detail at the prison to have eyes on the ground, not unlike how they handle guarding presidential children. They could decide to opt out of directly protecting the president, too, leaving things in the hands of prison staff. In that event, it might still be necessary to have an agent in the administration ready with a plan to extract the president in the event of violence.

It would (probably) consume the news

Picture all the headlines, the articles, the hours of television spent on Donald Trump's potential legal liabilities while in the Oval Office. Now try and imagine what the media landscape would look like if he, or any other president, were sent to prison. Even in the hyperactive news cycle of 21st century America, such an event would likely consume the media to the neglect of most any other issue, at least in the short term. Such a furor would likely incite public passions and further destabilize an already fractured citizenry, as happened in South American countries where an ex-president was convicted (per The Washington Post).

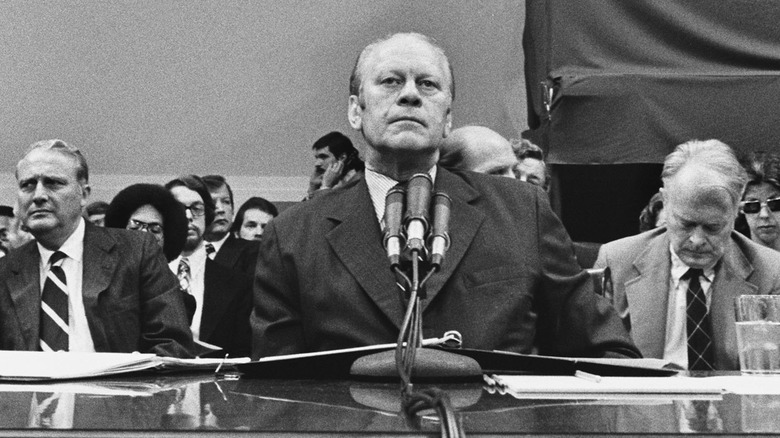

In an ideal world, the tempers of the moment wouldn't impede justice. If an ex-president committed serious crimes, appropriate punishment should be forthcoming. But in the world as it is, the disruption of such an event on the nation is at least worth considering. Gerald Ford cited exactly such concerns when he decided to pardon Richard Nixon, according to Constitution Daily. Nixon's resignation from office spared him impeachment, but indictments against him were being prepared when Ford took his place. "I was absolutely convinced," Ford told the House Judiciary Committee in 1974, "that if we had had [an] indictment, a trial, a conviction ... that the attention of the President, the Congress and the American people would have been diverted from the problems that we have to solve. And that was the principle reason for my granting of the pardon."

It may not prevent the ex-president from running again

The Constitution empowers the Senate to remove an impeached president from office should they vote to convict (per Vox). It also allows them to prevent the ex-president from holding federal office again — but it does not require they do so. If no such ban is put in place, there's no reason the former commander-in-chief couldn't run again, even if they had to do so behind bars.

There's more precedent for campaigning to be president from prison than there is for sending an ex-president there. Eugene V. Debs was the Socialist candidate in 1920, despite serving time for protesting World War I, and Keith Judd ran in West Virginia from prison in 2012, according to Slate. Perhaps not surprisingly, no such candidate has picked up a single electoral vote. Prison time, fairly or not, puts a certain stigma on a person when looking for any work, let alone high elected office.

But if incarceration isn't a technical disqualification from campaigning, it needn't be a drag on a candidate's chances either. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva served as Brazilian president from 2002 to 2010 before going to jail for corruption in 2018, according to The Guardian. If he hadn't already planned on retiring, the charges seemed the end of his political future. However, his conviction was annulled in 2021, and he announced a run against far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro. As of July 2022, Lula has the lead (per AS/COA).

It might strengthen the convict's political position

Generally speaking, people tend to be suspicious of those who've served jail time. It's not always right, it's not always fair, but it is a natural reaction. But as The Atlantic noted in discussing the possible conviction of an ex-president, that instinct tends to break down when the incarcerated is a public figure. That can certainly hold true when it comes to politics, where office holders are both an instrument of policy and a symbol of political movements. Party members can take any legal action against their candidate or incumbent as a politically-motivated attack, which has happened in South America (via The Washington Post).

A politician who wields sufficient charisma and media clout could probably count on a supercharged version of that scenario. Salon predicted such an occurrence should Donald Trump ever serve time and cited the example of Italy's Silvio Berlusconi. Like Trump, Berlusconi is a tycoon-turned-politician frequently accused of authoritarian tendencies. He was convicted of tax fraud in 2013. But, also like Trump, Berlusconi has cultivated a cult of personality and commands a significant number of loyal followers. He maintains a prominent place in the Italian right-wing, and despite his conviction, he maintained enough support among voters to win a seat in the European Parliament in 2019.

You could serve as president from prison

Let's suppose this long chain of events played out: A former president not subject to term limits was convicted and sent to prison, campaigned for reelection anyway, and managed to eke out a win. Let's also suppose that this president's sentence wasn't up by the time they began their term. How would that work? Surely, a president has to reside in the White House and be free to conduct affairs of state?

Not necessarily, according to Insider. The Constitution doesn't forbid convicts from running for president, and it doesn't require the president to reside anywhere. As long as you're at least 35 and a natural-born citizen in residence within the U.S. for at least 14 years, you meet the stated qualifications. Being a candidate wouldn't exempt the ex-president from prison rules, however. Campaigning would have to be done by proxies, and some states might attempt to restrict ballot access for the incarcerated.

If those hurdles were cleared and the jailed former commander-in-chief retook their position, they could technically sign or veto bills, make appointments, issue executive orders, and deliver a remote State of the Union address from their cell. If they were in federal prison, they could designate the White House a correctional facility to get back inside; a conviction at the state level wouldn't give them that opportunity. Of course, all this assumes the president wouldn't issue a self-pardon — an act of dubious legality never tested in the American system.

It could devolve into political persecution

In the United States, no one is meant to be above the law. Anyone, even a former president, should face legal consequences if they committed crimes. But there is always the danger that political machinations supersede justice. An ex-president could face credible accusations and go to trial for genuine crimes, but they could also face fabricated allegations from their ideological opponents. In the cases of the two presidents who faced impeachment before Donald Trump, Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, politics was a greater motivator than any legal wrongdoing, according to the Brookings Institute.

Impeachment is not a criminal trial, but there is an example in recent history of a presidential system probably sending an ex-president to jail on trumped-up charges. In 2019, The Intercept published secret documents indicating that Brazilian prosecutors worked against the left-wing Worker's Party in the 2018 election by targeting its former leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who had been president from 2002 to 2010. Lula was already jailed for alleged corruption charges brought by the 2014 Operation Car Wash probe, but the same prosecutors who ran that probe were the ones working against Lula's party.

The same documents showing conspiracy against the Worker's Party also showed the prosecutors conceding privately that they lacked strong evidence that Lula was guilty of corruption. In 2021, a Supreme Court judge annulled the conviction on the grounds that the court that had found Lula guilty lacked jurisdiction (per the BBC).

Are we about to find out what happens?

The prospect of a current or former president of the United States facing arrest stopped looking so theoretical on March 18, 2023, when Donald Trump took to his Truth Social platform to rave over what he claimed were pending indictments by the state of New York. There, Trump had been under investigation for hush payments made to the porn star Stormy Daniels; there was a question whether the payments were illegally camouflaged as a legal expense. It was a case that already sent Trump's former lawyer, Michael Cohen, to jail. Trump gave no evidence that he was about to be arrested, and a spokesperson had to explain that their client received no warning to that effect, but by the following Monday, it did appear that Trump would be indicted (per Politico).

Trump's Truth Social posts included calls for his supporters to protest and "take our nation back," rhetoric that many were quick to compare to his incendiary comments before and during the January 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol. But what protests did manifest immediately after his comments were small, and Trump's attorneys assured the press that their client would cooperate and peacefully surrender to law enforcement were he to be indicted (failure to do so would be grounds for an arrest warrant). Indicted individuals are handcuffed and fingerprinted, but Trump would almost certainly remain free without the need for bail ahead of a trial.