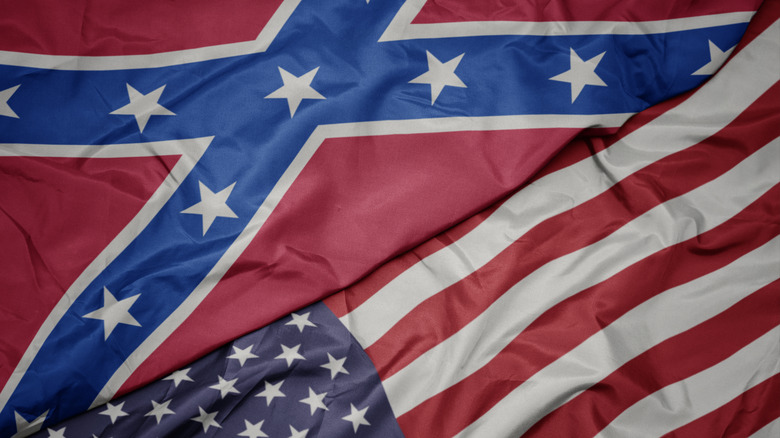

How The Confederate Constitution Was Different From The US Constitution

On March 11, 1861, the Confederate States of America (CSA) approved a new national constitution to serve as the nascent country's supreme law of the land. Upon a cursory reading of the Confederate Constitution (available alongside the U.S. version at Civil Discourse), readers will notice that it is a near-copy of the U.S. Constitution. Most sections are copied verbatim or near-verbatim with small additions that initially seem insignificant. So how different are the two documents?

The answer is that the two documents contain small differences that have huge ramifications. As FSU professor Randall Holcombe notes, the Confederate Constitution was basically an amended version of the U.S. Constitution according to Confederate views of federalism and states' rights, government overreach, and slavery — the major issues behind the American Civil War. A careful reading of the Confederate Constitution shows Holcombe's view to be correct. The document was created to restrain federal power, curb federal spending, protect the institution of slavery from federal interference, and ensure that states remained independent and sovereign entities within the new nation through restrictions on congressional amendments. Here are the two documents' most significant differences and why the Confederate framers made the changes.

States' rights over federal power

The American Constitution's preamble is fairly well-known: "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union..." The line stresses the formation of a larger whole from constituent sovereign parts, an idea captured in the national motto "e pluribus unum." As noted on American Experience, it did not deny the sovereignty of states; it just stressed their unity rather than their differences. The Confederate Constitution did the exact opposite.

The Confederate preamble begins similarly to the U.S. version. The only initial difference is the substitution of "United States" with "Confederate States." But the CSA document then shifts the importance from the Confederacy (i.e., the federal government) to its member states. The document stresses the character of the Confederacy as a voluntary union of states acting in their "sovereign and independent character" rather than an emphasis on the whole.

According to the Hendricks Lecture in Law and History, the preamble played two roles. First, it defined the states (and their rights) as the primary unit of government. It eliminated all references to the broad responsibilities of government (e.g., promoting the "general welfare"), which were viewed as starting points for federal overreach. Second, as noted by Civil War historian Kathleen Thompson on the website Civil Discourse, it justified the Confederate cause. Abraham Lincoln argued in his 1861 inaugural address (via Digital History) that states did not have the right to secede. In framing the Confederacy as a voluntary union, the Confederates highlighted that they did indeed have the right to leave the U.S.

The Confederate Constitution invokes God

The United States Constitution makes no reference to a higher power. The Declaration of Independence references the "Creator," who endows men with inalienable rights. As noted in the National Humanities Center, this language is deistic, but not explicitly Christian. One would expect "God the Father," "God Almighty" or something along those lines in an explicitly Christian declaration.

The CSA Constitution instead invoked the "favor and guidance of Almighty God." Per the National Humanities Center, the phrase was quite loaded. First, it was a clear declaration of the Confederacy's Christian Protestant identity in a case of the merger of religious and political speech — a common feature of the Civil War era on both sides. Before 1860, religious rhetoric in politics had often been the domain of New England politicians raised in the old Puritan milieu.

Second, the phrase was a declaration that the torch of God's favor had passed from the New England elites, who had played an outsized role in founding the United States, to the new Confederate nation in the South. Episcopalian Rev. William Butler's sermon in Virginia best captured the sentiment: Secession and the formation of the Confederacy were an opportunity to execute God's plans "by holy, individual self-consecration." Thus, the Confederacy was not simply a bid to break away. It was divinely ordained to continue the American experiment. Nevertheless, the CSA Constitution (via Civil Discourse) retained the U.S. First Amendment in Article I, Sec. 9.12, forbidding federally established religion, while Article VI forbade any religious tests for office.

The CSA Constitution mentions slavery by name

The United States Constitution interestingly does not use the word "slavery" anywhere in the text. As the Bill of Rights Institute notes, the Founders were conflicted and divided on the issue. The Declaration of Independence stated as one of its "self-evident truths" that all men were created equal. A man cannot own another man as property if they are indeed created equal. But as noted in the Constitutional Rights Foundation's journal Bill of Rights in Action, the Founders had to convince the slaveholding Southern states to join or remain in the United States. Furthermore, a handful of the Founders, including George Washington, were enslavers. So they compromised and tiptoed around the issue, completely omitting the word and its derivatives from the document.

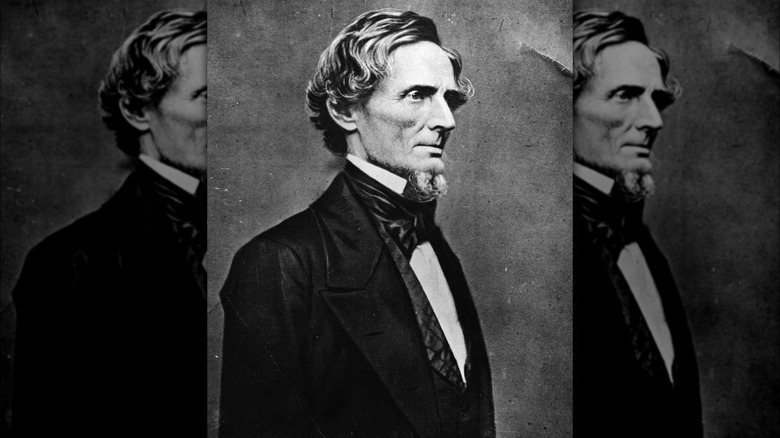

By the time the Confederate Constitution was drafted, slavery had become one of the major issues dividing the Confederacy from the United States. In fact, CSA Vice President Alexander Stephens called the idea of white supremacy over Africans a cornerstone of the Confederate nation. He also condemned the Constitution's logical conclusion (the "equality of races") as a major error. Given this, it is no surprise that the Confederate Constitution did not tiptoe around the issue of slavery but even partially enshrined the practice as a right.

Slavery was partially enshrined as a right

Among the most contentious issues around secession were the expansion of slavery into U.S. Western territories and freedom of movement between free and slave states. In Dred Scott v. Sandford (via Oyez), the Supreme Court ruled that enslaved people were not U.S. citizens and therefore not entitled to constitutional protections — even in free states. Exacerbating these problems were battles between pro- and anti-slavery supporters in territories such as "Bleeding Kansas" (via Britannica). Thus, the Confederacy placed some national protections on slavery with Article I, Sec. 9.4 (via Civil Discourse), which forbade infringement on slavery.

This was not the blanket protection of slavery it appears, however. Sec. 9.4 of the CSA Constitution is a list of checks on congressional power, similar to its U.S. counterpart. As FSU Professor Randall Holcombe and Notre Dame Professor Donald Stelluto both note, the section only forbade Congress from banning slavery — not the states. This position was consistent with pre-1865 U.S. attitudes, including that of Abraham Lincoln, who in 1861 argued that slavery was beyond the federal purview. States were free to forbid it, as New York and Pennsylvania did in 1828 and 1847 respectively (via Marquette University).

All that said, Confederate citizens' kept a "right of transit and sojourn" with their slaves (Article IV, sec. 2.1 considers them property) when passing through other states, so despite no blanket protections, slavery was still clearly an important part of the Confederate state. Meanwhile, Congress maintained full authority over slavery in Confederate territories yet to achieve statehood, per Article IV, sec. 3.3.

The international slave trade was banned

Among the contentious debates of the 1787 Constitutional Convention was the importation of African people through the international slave trade. According to the Constitutional Rights Foundation journal Bill of Rights in Action, the Founders decided to shelve the issue until 1808 as a compromise. The Southern economy was heavily dependent upon slave labor, and bringing those states into the Union was going to be impossible without offering them concessions on slavery. In 1808, the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves (via National Archives) was passed, and official American participation in the international slave trade ended. Interstate trade, however, was still legal.

The Confederate Constitution, drafted more than 50 years after the ban, surprisingly retained it and incorporated it as a constitutional law. It may seem counterintuitive, given that, according to the journal Louisiana History, some Confederate politicians were in favor of restarting the trade. Instead, Article I, sec 9.1 (via Civil Discourse) banned the importation of all African slaves except from the slave-holding states that had remained loyal to the USA. Section 9.2 of the same article also gave the Confederate Congress the right to regulate and ban the slave trade with the United States in the future.

So why the ban? Historian Nick Sacco has argued that the Confederacy had little choice. Although hoping to maintain slavery, it needed Franco-British support to triumph against the more populated and industrialized United States. The ban on slave trading was an overture to Britain and France, which had both abolished slavery decades before.

The president was limited to one six-year term with a line-item veto

The Confederate government was tripartite like its U.S. counterpart, but the office of the presidency developed a few small but significant differences. Most significantly, according to the CSA Constitution (via Civil Discourse), the president was limited to a single six-year term — unlike the U.S. president, who at the time could serve unlimited terms. (The two-term limit via the 22nd Amendment only passed in 1951.)

According to Notre Dame Professor Donald Stelluto, the law was meant to curb partisan politics during re-election campaigns. Incumbent politicians often made concessions to political rivals and patronage appointments that were not always in the national interest to secure re-election. By restricting the executive to one longer term, the Confederate framers argued that the president could pursue the national interest free of political pressure while restricting the national bureaucracy's size.

The president also received a line-item veto, particularly in budgetary matters. The mechanism was meant to curb legislative abuse and appropriations giveaways to special interests. According to the Political Science Quarterly, it was the first time such a provision had been codified in North American law. (The U.S. president still doesn't have this power.) As Prof. Stelluto notes, the veto checked congressional power and ensured that the federal government could not engage in cronyism with special interests. And if it did, the president could halt it.

The CSA office requirements were a bit more pragmatic

According to the White House, a candidate for U.S. president must meet three requirements. The candidate must be a "natural-born citizen," at least 35 years of age, and have resided in the United States for a minimum of 14 years before running. Article II, Sec. 1.7 (via Civil Discourse) of the Confederate Constitution had almost exactly the same requirements — except it had to fine-tune them for practical purposes.

The Confederacy was a new state, so naturally its citizens could not meet the residency and natural-born status criteria. The CSA Constitution was drafted on March 11, 1861, while secession had begun four months before. So the framers inserted an additional provision: Any Confederate citizen born on U.S. soil before December 20, 1861 (the date of South Carolina's secession), was eligible for the presidency. It is unclear how the residency requirement applied to former U.S. citizens, but the text suggests that as long as candidates had lived in their states for 14 years — including when those states were part of the United States— they would be eligible to run. Otherwise, the Confederacy would have had to wait until after 1875 to have any eligible candidates!

Article I, Sec. 3.3 of the Confederate Constitution also deviated slightly from its U.S. counterpart for the same reason. While the U.S. Constitution required U.S. senators to have lived in the country for 9 years, Civil Discourse notes that this was impossible in the newly created Confederacy. So the requirement was dropped.

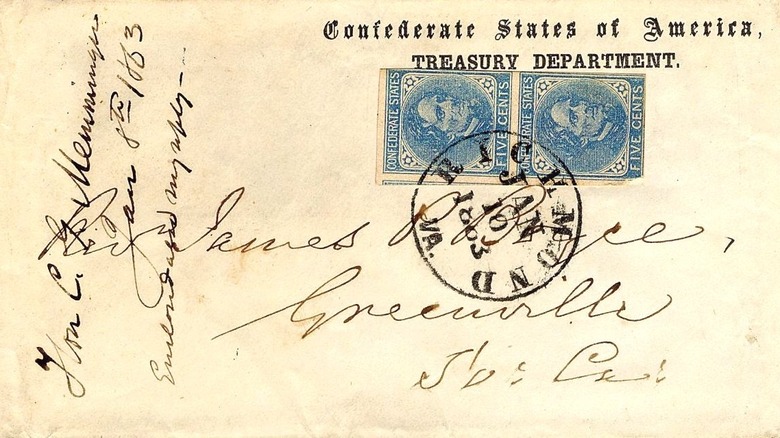

The Post Office didn't get government funding

The United States Postal Service, as the name implies, is a federal agency that receives government funding. Despite calls to abolish it, this is impossible without congressional action because the Constitution (via Constitution Center) gives Congress power over postal routes and services. The Confederate Constitution, however, catered to an alternative view that forced the postal service to be self-sustaining.

The CSA Constitution's Article I, Sec. 7.7 (via Civil Discourse), empowered the Confederate Congress to regulate the postal service, as was the case in the U.S. However, there was one major difference. The Confederate Postal Service would be government funded — like the USPS — but only for the first two years of its existence. On March 1, 1863, Congress would cut the postal service off and expect it to pay for itself through revenues generated from services rendered.

As noted in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly, the system ended up collapsing. As the Civil War progressed, the Confederate Postal Service could not keep up with its salaries and expenditures. Its revenues were constantly debased through mass printing (and counterfeiting) of the Confederate dollar. The ravages of war and constant traffic of soldiers led to delays and cancellations of service along major routes. Finally, it clashed with the War Department, which tried to conscript its workers into the Confederate Army. When its workers — who were originally exempt from the draft — were arrested, the service had to find replacements at a cost.

Congress could not amend the CSA constitution

In the United States, there are two ways to propose constitutional amendments. According to the National Archives, one way is by a convention of states if two-thirds of the legislatures agree. The other way is through a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress. So far, no amendments have come through the former process — only the latter. That was one of the Confederacy's major gripes. Southern Democrats feared that the federal government would use its power to rewrite the Constitution even in the face of state and public opposition.

Per Prof. Donald Stelluto, the Confederate Constitution simply banned Congress from amending the document. Instead, as seen in Article V, sec. 1.1, the Confederate Constitution could only be amended by constitutional convention if a minimum of three (out of seven at the time) states requested it. The measure, per Stelluto, was meant to promote debate over internal differences and give citizens of the Confederacy a greater say in their country's affairs.

In the end, the measure made amending the Constitution easier. Alongside the three-state requirement, only two-thirds of the states had to approve an amendment, as opposed to the three-fourths majority required in the United States.

Bills had to be about one topic and one topic only

According to Prof. Donald Stelluto, the Confederates took issue with the practice of advancing potentially unpopular legislation through the controversial practice of bill riders. Put simply, whenever a congressional faction failed to advance a bill, it was commonplace (as it is today) to attach it to another bill as a rider — even if it was tangentially related or completely irrelevant to the main subject of the second bill. According to the American Battlefield Trust, the 1848 Wilmot Proviso, which called for a ban on slavery in territories conquered from Mexico, was one of these riders, and even though it failed, it was an alarm bell for Southerners seeking to preserve slavery.

To prevent this kind of legislative abuse, the Article I, Sec. 9.20 of the Confederate Constitution limited all congressional bills to a single topic. This provision, which is absent from the American Constitution, was meant to keep politicians accountable to their constituents and prevent the covert expansion of federal power. Politicians had to vote publicly on each individual issue, rather than ramming through unpopular or controversial legislation as a rider attached to another bill. It also kept bills short and ensured that legislators could actually read them entirely.

The interstate commerce clause was practically void

Per the Library of Congress, under the Articles of Confederation, the U.S. Congress did not have the authority to regulate interstate commerce. Realizing the need for some federal oversight over internal infrastructure to unite the country, the framers gave Congress regulatory power over interstate commerce in 1787. Per the Greensboro News and Record, the clause allowed Congress to appropriate money for infrastructure projects ranging from railroads to roads and waterways between multiple states. It also gave the federal government discretion over investment locations. But this also raised the issue of privileging some areas over others with federal dollars.

The Confederate Constitution (via Civil Discourse) defanged the interstate commerce clause with an additional stipulation. Although the Confederate Congress retained regulatory power over foreign commerce, it was explicitly banned from appropriating money for infrastructure projects to facilitate interstate commerce. The only exceptions applied to a handful of navigation safeguards such as lighthouses, buoys, harbors, and riverine obstructions. As the Mises Institute notes, the Confederate framers considered "internal improvements" to be "pork-barrel spending" — spending meant to shunt money to a particular district or special interest and ran the risk of privileging one area over another. So this clause is no surprise given the preeminence of states' rights in the CSA Constitution, and it was accompanied with more explicit provisions regarding federal subsidies.

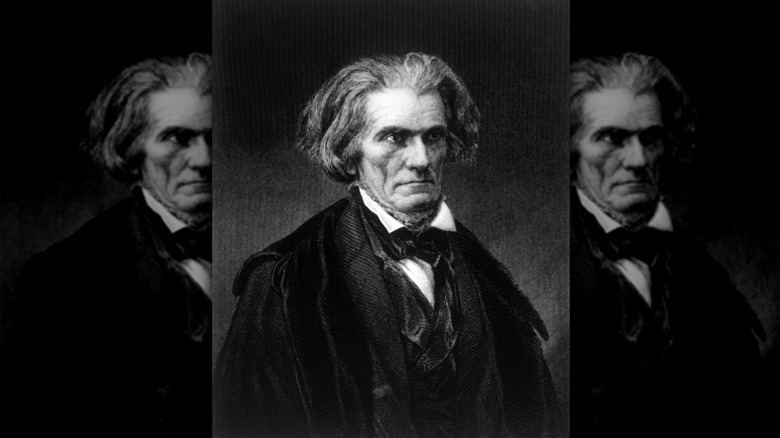

Congress could not favor one industry over another

Besides slavery and states' rights, economic tension between the agricultural South and the industrializing North simmered on the eve of the Civil War. According to the U.S. House of Representatives, tariffs caused a number of conflicts, most famously the debate over the 1828 Tariff of Abominations.

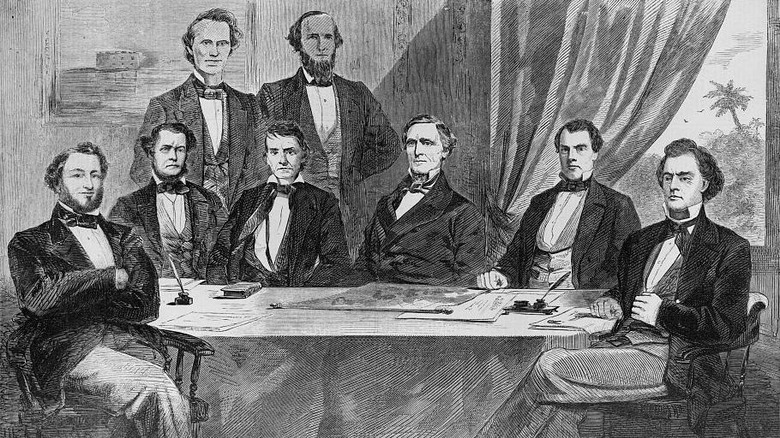

According to the magazine The Economic Historian, the tariff was meant to protect Northern industry and agriculture against foreign competition through high import tariffs. Although some Southerners tried to kill the tariff by arguing for much higher rates, it passed anyway and caused economic chaos south of the Mason-Dixon line. The mostly agricultural South suddenly found itself paying considerably higher prices for imports. Simultaneously, European countries hit the United States with tariffs on Southern cotton, cutting into Dixie planters' profits. South Carolina nullified the tariff after exhortations from Vice President John Calhoun (pictured above) before an 1833 compromise averted a potential constitutional crisis and secession.

Southerners viewed the 1828 tariff as a giveaway to New England industrialists and farmers at planters' expense. As the Mises Institute explains, the Confederate framers argued that this level of government intervention originated in the broad federal powers of Article I, Sec. 8.1 over taxation, tariff, and spending. To avoid a repeat of 1828, the Confederates forbade Congress from passing any duties or bounties on imports from foreign nations that would benefit one branch of industry over another.

States could tax one another's commerce

Instead of placing interstate commerce fully under federal authority, the Confederate Constitution delegated it to the states. Under the U.S. Constitution (via Cornell Legal Information Institute), Article I, Sec. 9.6 prohibits Congress from giving any port commercial or revenue preferences based on the state they were located in. The Confederate Constitution copied this part verbatim in Sec. 9.7. But the Confederate version (via Civil Discourse) omits the rest of the section.

In the U.S. Constitution, Sec. 9.6 also prohibits states from collecting duties on traffic crossing over from other states. For instance, New York could not tax a ship docking from South Carolina or vice versa. The Confederacy, however, always concerned with states' rights and a lean federal government, cut Congress out of the equation completely.

Civil Discourse suggests that in the absence of this section, Confederate states had the right to tax one another's commerce and enter into agreements with one another. In this regard, Confederate states operated as de facto independent countries, free to impose their own excises, duties, and other taxes upon shipping within the Confederacy. This section of the Confederate Constitution hearkens back to the Articles of Confederation, which as mentioned earlier, gave states the right to regulate their own commercial affairs without federal involvement — including the provision of credit lines and the emission of paper currency.

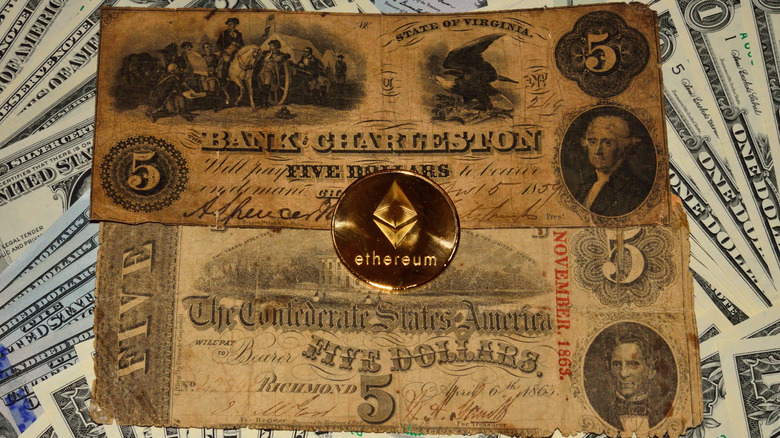

States could emit bills of credit

The American and Confederate Constitutions both agree that only gold and silver are legal tender for the payment of debts among states. Article I, sec. 10.1 is very clear in this regard and also prohibits American states from issuing any bills of credit (aka paper currency). This provision was inserted to prevent states from issuing depreciable paper currency on the state's credit — as had happened during the Articles of Confederation and the Revolution.

The Confederacy did away with the prohibition on state currency. According to UNC, Confederate states issued their own banknotes as paper currency. This provision was likely made to allow the states to raise more money for the war. Since the states did not have enough precious metal on hand to pay the war's costs, they resorted to paper and inflation.

Now, the bills (like modern Federal Reserve Notes) were not money — merely promises to pay money after the Civil War. But this constitutional workaround was also the system's greatest weakness. Neither the banknotes issued from the Confederate government nor those issued by states were backed by anything tangible. The federal government and the state of Mississippi attempted to back some currency and bonds with cotton, as noted by Texas A&M, but the measure did not check the growth of the Confederate currency supply as the war progressed. Unsurprisingly, per Investopedia, the Confederate dollar crumbled under rampant inflation (and counterfeiting) as Richmond debased the currency to pay war effort, becoming what one Confederate woman described as "waste paper."

The Confederate Constitution curbed recess appointments

In 2012, Barack Obama caused a small controversy after he appointed Richard Cordray to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau when the Senate was out of session. According to Reuters, although his opponents objected, this appointment — known as a recess appointment — was perfectly legal. When the Senate is in recess, the president can temporarily fill an office thanks to the Recess Appointment Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

The recess clause also provides a way for a president to insert a temporary appointment that Congress had rejected, something that the Confederates appear to have viewed as an abuse of federal power. At least that is the impression one gets from the restrictions placed upon recess appointments in an otherwise identical recess clause.

The Confederate Constitution (via Civil Discourse) added an additional provision to the recess clause that prevented the president from appointing any nominee to the Confederate cabinet that the Confederate Senate had already voted down. The appointments were temporary, as in the USA. Most likely, this was passed to provide a check on the president's power by preventing him from circumventing the will of the states when their representatives were not around to vote on the nominee.

Appropriations bills were set in stone

Article I, Sec. 9.7 allows Congress to appropriate money from the U.S. treasury to fund the workings of the government. However, these bills can exceed 1,000 pages (e.g. the 2022 appropriations bill) and contain earmarked funds (via Bloomberg Government) that can go to special interests. Now, the problem of bloated appropriations is nothing new. Given the Confederacy's severe restrictions on the practice, it was probably an antebellum issue too, per FSU's Prof. Randall Holcombe.

As Holcombe notes, the Confederate Constitution's Article I, Sec. 9.10 (via Civil Discourse) placed strict requirements for any congressional appropriation from the Confederate treasury. Each appropriations bill had to specify the exact amount requested for each appropriation in federal dollars subject to approval by two-thirds majority per sec. 9 of the same article if the bill did not come from the president. Appropriations bills were also subject to an one-topic limit, making it difficult for politicians could not hide pet projects in long bills that could be otherwise deemed wasteful.

Lastly, Congress could not pay out any additional money to any "public contractor, officer, agent, or servant" without passing a new bill first, per Prof. Holcomb. This way, no permanent entitlements or projects could be created that could prove a drain on the national treasury. If an existing project was proving to be wasteful or a dead-end, Congress had to vote to re-fund it — placing them at the mercy of their constituents if they voted to continue spending.