The Part Of World War II's Bangka Island Massacre That Remained Hidden For Decades

This article contains mentions of violence and sexual assault.

War is always a messy business. Despite that fact, many have been fought over the course of human history. The reasons and outcomes may vary, but even so, war results in death and destruction. Though wars often seem disorganized or chaotic, they do have general rules of combat (look no further than the Geneva Conventions for the biggest example). However, sometimes there are still actions taken during wartime that fall outside these rules, and result in what we know today as war crimes (via Britannica).

During World War II, most of the fighting took place either in Europe or in and around the islands of the Pacific Ocean. Located in the Pacific, Bangka is one of these islands — it, too, was involved in the war, most of which occurred during its occupation by Japanese forces (via Britannica). It was also on this particular island that one of the war's many atrocities took place, and resulted in the deaths of nearly 100 people. The massacre at Bangka was in and of itself a horrible event, but it was the alleged cover-up later that made this tragedy even worse.

The history of Bangka dictated its strategic importance during World War II

For the uninitiated, Southeast Asia's Bangka island is located east of Sumatra and lies south of the South China Sea. According to Britannica, the island possesses a somewhat diverse landscape, ranging from dry soil to swampy coasts to large hills situated within the island's interior. The island also possesses many natural resources including tin, lead, copper, and gold, and is used to grow crops like rice, coffee, and pepper.

When it comes to general governance, Bangka has changed hands over the years. Historically populated by Malay Muslims, the British Empire gained control from the Sultan of Palembang, the ruler of an area of Sumatra, in 1812, per Britannica. Two years later, it was then traded by the British to the Dutch in 1814. Though it remained under Dutch control for over a century, it was eventually taken over by Japanese forces in 1942 during World War II before they released it after the Allies' defeat of the Axis powers in 1945. But within that time — during the first year of Japanese occupation, in fact — the stage was set for what would become a massacre to take place on Bangka's shores.

A hastily organized evacuation set the stage

In January 1942, news that Japanese soldiers had raped and murdered British nurses in Singapore reached the senior officers of the SS Vyner Brooke, as was summarized in a 2022 article about the event authored by writer Ben Rodin and published by the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Journal. According to later accounts, officials on the ship immediately made plans to evacuate civilians and staff from Singapore, which was one of the ports frequently visited by the vessel. The SS Vyner Brooke departed on February 12, 1942, with 181 people on board — a massive population increase for a vessel that typically carried 12 passengers and 47 crew at a given time. The majority of the passengers on board were civilian women and children, along with 65 Australian nurses.

According to Rodin's write-up, the conditions aboard the ship were less than ideal, hot, humid, and seriously uncomfortable, as. Despite the discomfort, the ship managed to outmaneuver the Japanese military for almost two days, but their good fortune ran out on February 14. As the ship attempted to get to their destination, the Sumatran city of Palembang, they were bombarded by military aircraft and assaulted by warship machine guns. The ship was too damaged to stay afloat and ultimately sank (though it is estimated that around 150 of those on board were able to make it to shore). But unfortunately for many of the survivors, their ordeal was not over — and an awful fate awaited them.

The massacre at Bangka left few survivors

According to Ben Rodin's piece for the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Journal, passengers on the SS Vyner Brooke who made it to shore included British servicemen, civilians, and some of the Australian nurses who had come aboard before departing from Singapore. After the ship sank, the group of survivors ultimately decided to surrender to Japanese forces. It was a choice that had catastrophic ramifications. On February 16, 1942, following their surrender, the Japanese soldiers took their captives to Radji Beach and separated them into two groups by gender, per Australia's Huffington Post. The men were taken away and executed. When the soldiers returned, the group of 22 nurses was ordered to walk into the ocean. As they did, they were shot from behind by machine guns.

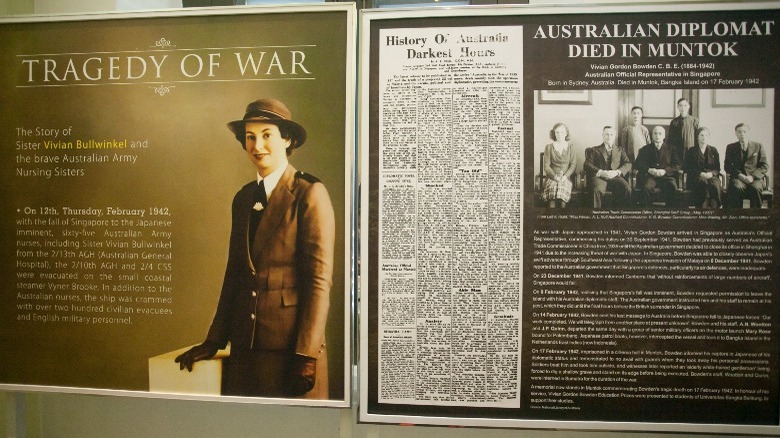

Out of those who were gunned down that day remained two survivors: Sister Vivian Bullwinkel (pictured above) and British Army Private Cecil Kingsley (via the Australian War Memorial website). The two managed to evade capture for 12 days before the severity of their wounds necessitated their surrender to Japanese forces. Kingsley ultimately died, and Bullwinkel was placed into a women's camp where she was imprisoned for over three years.

The massacre at Bangka was covered up for years

Sister Vivian Bullwinkel returned to her homeland of Australia after the war concluded in 1945 following the defeat of the Axis powers, among which included the Japanese empire. Two years later, the former prisoner of war was asked to testify about her experience at Bangka during the Tokyo War Crimes Trials headed by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (via the National WWII Museum website). Bullwinkel's testimony led to the conviction of a Japanese sergeant for his part in the massacre and resulted in a 12-year prison sentence for his crimes (via the Australian Broadcasting Corporation).

Despite the veneer of justice served, there was more to Bullwinkel's story — parts that the army nurse was reportedly forced to leave out. Not only had the nurses been gunned down in cold blood, but they were also sexually assaulted before they were killed. According to a BBC report published in 2019, Bullwinkel was legally prohibited by the Australian government from discussing the assaults during the trials. Reportedly, accusations of sexual assault were an "ill-kept secret" that many of the nurses were violated before they were killed, but Bullwinkel was literally ordered by the government to keep this information to herself (via the ABC).

The truth about the Bangka massacre has finally come to light

It was not until decades after the massacre at Bangka that the truth started to emerge. Despite this, over the years Vivian Bullwinkel reportedly discussed these atrocities with others, including a broadcaster before her death in 2000, per the BBC. The Australian government the persons who committed these crimes are still unknown as of this writing, and as such have avoided punishment. There have been multiple historians and professors who have and continue to investigate these allegations. In their research, they have found corroborating evidence — such as the clothes Vivian Bullwinkel was wearing that day — as well as firsthand testimony from others who witnessed the aftermath.

According to her website, historian Lynette Silver has requested that the Australian War Memorial amend its information on the massacre at Bangka to include these allegations. Additionally, her work has opened the door for families of the deceased to petition the government to open an investigation into these new allegations. Silver, who published a book about Bullwinkel and the massacre in 2019, told the BBC in an interview that the government was trying to "protect" these women and their families from the stigma attached to sexual assault and victimization, as during this time it was erroneously seen as a reputational "fate worse than death."

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).