Ideas That Changed The Course Of Humanity

History is full of great ideas. Some of those ideas gave us simple comforts, novel gadgets, and luxuries we don't really need. Other ideas never really went anywhere at all. But some of those great ideas had a profound impact on the way we live, and ultimately on the course of history itself. Let's check out some of humanity's most influential ideas, and how those ideas helped make the world what it is today.

Salted meat

Americans love salt almost as much as we love our smartphones. We dump way too much of it on our popcorn, we secretly add it to Grandma's otherwise perfect gravy, and we scorn "reduced salt" potato chips and low-sodium beef stock. But salt hasn't always been a mere flavor enhancer and causer of life-threatening chronic high blood pressure. This humble mineral made food preservation possible, and it also helped establish international trade routes.

Before salt, food started to spoil on pretty much the same day you killed it. You probably know you shouldn't leave animal products unrefrigerated for more than two hours — now imagine you have a whole moose, it's summer, and the refrigerator hasn't been invented yet.

Salt not only helped people ward off food-borne illnesses, it also made it possible for them to live in permanent communities. Instead of eating meat immediately, it could be put away for lean times. That meant less waste and less work overall, which freed people up to do other things with their time, like play Minecraft on smartphones.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, salt was difficult to harvest and valuable enough that it was sometimes used as currency — in fact the word "salary" has its roots in the word "salt" because Roman soldiers were sometimes paid in salt rations. Salt was so prized that it was traded internationally, and vast "salt routes" were established between salt-producing nations and salt-buying nations centuries before it was really practical to do that kind of traveling.

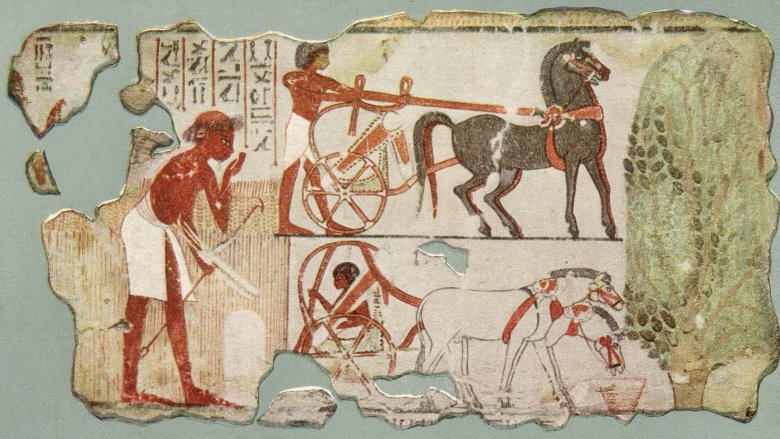

The domestication of the horse

Domestication fundamentally changed the way human beings lived. The dog helped us capture game, and gave us friendship and protection. Cows and chickens gave us ready food sources that didn't have to be hunted. The cat ... um, cats are fluffy. But the horse, more than any other animal, changed everything. The horse altered the size of the world.

According to ThoughtCo, evidence that people were riding horses goes all the way back to Kazakhstan between 5,000 and 5,500 years ago. No one is really sure who first had the inspired idea to sit on the back of a half-ton animal that assumes anything on its back is a large predator. But someone did, and that person (or whoever witnessed that person's death and said "I can top that") launched a new era of mobility and warfare. Horses made it possible for people to travel long distances and to bring their stuff with them. They made trade routes longer and more profitable. And they gave armies a distinct advantage: Foot soldiers almost didn't stand a chance against the onslaught of mounted warriors.

Today, people think of horses either as participants in elite sporting events or the stuff of little girls' Christmas dreams, but the historical relationship between humans and horses is much more profound. If that one person had never been inspired to mount up for the first time, the human story would have had a completely different trajectory.

Zero

Guess what else changed the course of humanity? Nothing. Literally, nothing. Zero. The Romans used to count using a convoluted system of Latin letters. This resulted in ridiculously long numbers like MDCCCLXXXVIII, which actually represents the relatively short corresponding number 1,888.

The concept of zero is really nothing new — the Babylonians had a symbol for it 2,000 years ago. But the widespread use of zero as a number really didn't start to catch on until seventh-century India, when an astronomer called Brahmagupta realized he could use zero ("shunya") as a placeholder in mathematical calculations. From there, the idea traveled to the Middle East, where it became a part of the familiar Arabic number system.

That should have been the end of the story, but it's not. Like certain books, Galileo, and Carol in that one episode of The Walking Dead, zero was banished during the Middle Ages partly because it was Arabic (and most of Europe was crusading against the Arabs at the time) and partly because it was too easy to add zeros to the ends of numbers to inflate them. Zero wasn't really taken seriously by the West for another century, when it was adopted by Western scientists, scholars, and mathematicians.

Once zero finally did become a part of the modern numbering system, it made complex mathematical calculations possible, which in turn made it possible for generations of math teachers to mentally torture generations of school children.

Movable type

Movable type (also known as the printing press) arguably has even more significance to the history of information than the internet, if you can believe that. Before the printing press, the only way to reprint a book was to meticulously transcribe it by hand. This practice could take months and caused widespread hand-cramping in thousands of dedicated monks. It also made books rare and expensive — objects that could only be possessed by religious institutions or the elite.

Johannes Gutenberg knew there had to be a better way, and it definitely wasn't the hand-carved wooden blocks some people were using to print books, which were fragile, didn't last very long, and took a ridiculously long time to create. His idea was to make metal molds that could produce identical individual letters, then line them up to make words and rearrange them as often as necessary, allowing for much faster and more efficient production of printed pages.

Like many great inventions, there is some question as to whether Gutenberg was the first to use movable type. According to OpenLearn, a system of movable type was being used in Korea years before Gutenberg had the idea. But regardless, the process caught on and was instrumental in educating a once-illiterate population. The printing press not only made books accessible to the masses, it also made newspapers possible, and that led to educated citizens and even more book learning.

The 24-hour day

It's hard to imagine living in a world where the Sun is the only measure of time. No modern person ever looks up at the sky when trying to figure out when they have to be at work or when they're supposed to show up at their sister's wedding. But it was only a few hundred years ago that time was literally just counted in days — there was sunrise, sunset, noon, and night, which meant there was no such thing as bedtime, dinnertime, or an alarm clock. You slept when you were tired, you ate when you were hungry, and you woke up when you woke up.

Then, in 1657, the balance spring was invented, and suddenly it was possible to divide the day up into small, evenly spaced chunks of time. Now the day could be measured by hours, minutes, and seconds. As long as everyone had a clock, human activities could be synchronized. This led to the invention of mealtimes, bedtimes, and the schedule (which was clearly a mistake, in retrospect). And as clocks got smaller, it became possible for people to look pointedly at their watches, the universal symbol for "I'm really annoyed at you for being late."

Whether or not all of this is really a good thing or the most depressing thing that ever happened to the human race is totally subjective, but either way you can't argue that the 24-hour day changed everything.

Paper money

Currency used to be made from valuable metals like silver and gold. That makes perfect sense — when you wanted to trade something for valuable goods, you used something that had universally accepted value. But precious metals have major drawbacks. First, they're heavy. If you've got a lot of silver coins, they're going to be awkward to carry around, and if your purse is fat enough it might even make you a target for highway bandits and Robin Hood. Second, an unscrupulous person could clip the edges of a coin, melt down the clippings, and make new coins, thus devaluing the original currency.

Paper money solved these problems. Bills were actually in use in China more than 2,000 years ago, but it wasn't until the 1600s that the idea caught on in Europe. People were just not convinced that an otherwise worthless piece of paper could have value, even though the bank promised them that, whenever needed, they could bring that worthless piece of paper back and exchange it for its face value in silver and gold.

Once people were comfortable with the idea of paper currency, its practicality became pretty obvious. You could carry around large denominations as easily as small ones — a $100 bill, for example, weighs exactly as much as a $1 bill — and it also had larger implications, like making it possible for nations to trade in each other's currencies, and (rather ominously) the potential for nations to print more currency than could be supported by actual precious metal.

Sanitation

The next time you flush your toilet, you ought to give thanks to the humble people who somewhere, somehow, some time, realized that living in filth was probably not good for your health.

Before flushing toilets we had outhouses, and before outhouses people pooped in ditches or pans and then dumped it into rivers or just right out on the city streets. Awesome. And even today there are billions (yes, billions) of people living without toilets, which either directly or indirectly leads to the deaths of 6,000 children a day.

Modern sanitation has not only directed the world's poop away from the world's water sources (at least in developed nations), it has also contributed to such enlightened ideas as soap, which ultimately led to the practice of washing your hands after pooping, washing your hands before dinner, and washing your hands between that autopsy you did in the morning and the baby you delivered in the afternoon. Hand washing, as every kid with a parent understands, is the best way to prevent dangerous bacteria and viruses from causing illness and spreading from person to person. Do you know how the common stomach illness norovirus spreads? It's the oral-fecal route. Wash your hands.

Therapy

People are no longer routinely institutionalized for mental health issues, but the stigma remains — the U.S. Census estimatesthe number of people in America with "diagnosable mental disorders" is around 57.7 million, and yet only 60 percent of sufferers will seek treatment. The sad truth is that mental health disorders are still thought of as weaknesses in character rather than genuine medical problems, and those attitudes discourage people from getting the help they need.

Therapy as a way of treating mental health disorders has really only been around since Philippe Pinel in the late 18th century, who was one of the first to consider talking to patients instead of chaining them to their beds, bleeding them, or giving them a near-death experience in a pool of water. And even after Sigmund Freud pioneered the widespread practice of psychotherapy, cruel "treatments" like electroconvulsive shock therapy and lobotomy were still used well into the 20th century.

But therapy isn't just for people with diagnosable mental disorders — therapy can help people lose weight, cope with loss, end addiction, and navigate debilitating illnesses. A 2017 review of 207 psychological studies found that just three months of therapy can have the same ability to reduce neuroticism, which usually decreases as you get older, as "30 to 40 years of adulthood." Neuroticism, in case you're not sure, is the anxiety, self-doubt, frustration, and depression that many of us suffer from at some point in our lives.

Batteries

Think where we would be today without batteries. Our smartphones would have super-long cords that we'd have to drag around with us wherever we go because fathoming the nonexistence of the smartphone is next to impossible.

Batteries shaped the modern world in ways we can't even begin to quantify. The word "battery" was actually coined by Ben Franklin, he who ... did not ... fly kites in lightning storms and survive. But a true battery wasn't invented until a half century later, when Alessandro Volta made one out of a stack of alternating copper and zinc disks, and cardboard soaked in brine. This proved difficult to put into a Walkman, so the world had to wait another 37 years for "the Daniell cell," which was practical enough to power telephones and doorbells. Then finally, another 50 years later, Carl Gassner invented "the dry cell," which was the first battery that didn't contain liquid and therefore wouldn't leak when tipped sideways or turned upside-down. That doesn't sound like much of an innovation, but imagine if you could only use your smartphone in the portrait orientation. What a world, right?

The battery not only made smartphones possible (which, it can't be said enough, is the only thing that matters); it also made it possible for people to carry flashlights, wear hearing aids, and use watches that don't require daily winding. And today, batteries can power cars or entire buildings. Without them, the world would be a pretty different place.

Air conditioning

Escaping the heat isn't just a question of personal comfort. Historically, a heat wave before air conditioning could be deadly, or at least lead to a nationwide epidemic of decreased worker productivity. It's difficult to get anything done when you're uncomfortably hot. It's hard to think, and it's hard to sleep, and a lack of sleep makes it even harder to think.

Before air conditioning, heat waves controlled people. According to The Atlantic, a hot climate even influenced the ways homes were designed — from extra windows to outdoor sleeping areas for nights when it was too stiflingly oppressive to stay indoors. During a heat wave, people skipped work to nap or go swimming, or just sprawl in the shade with handheld fans. When it was particularly bad, people could (and still can) die from hyperthermia.

The first air conditioner arrived in 1902 but it wasn't meant to keep anyone comfortable — it was used at a publishing house to stop paper from wrinkling in humid conditions. It wasn't long before people realized the broader potential of the technology, and by the 1920s, small air conditioners could be installed in buildings. And here's a fun fact — the movie industry as we know it probably wouldn't exist without A/C. During the Golden Age of Hollywood, an air-conditioned theater was as much an attraction as the movie it was showing. Today, air conditioning is everywhere, from homes to shopping centers, although this has ultimately led to rolling blackouts and $500 air conditioning bills. Hooray for progress.

Refrigeration

There was a time not so very long ago when you couldn't get up from the couch in a moment of boredom and stare vacantly at the contents of your fridge, wishing that something tasty would magically appear between the sour cream and that Tupperware container full of tuna casserole from three weeks ago. The refrigerator didn't become available until the first half of the 20th century. Before that, people used "ice boxes," which were literally boxes full of ice. In those days, it was hard to control the temperature of stored food, which meant that despite your best efforts you might end up giving your family food poisoning anyway.

The refrigerator changed all of that. According to the Star Tribune, refrigeration made it possible to transport food across the country, rather than just across town, so farmers could sell veggies no one had ever heard of to people who lived in different climates. That helped diversify the American diet, and it brought down costs, too, since perishable food now had a longer lifespan. But on the flip side, small, neighborhood grocers started to lose to big, corporate supermarkets, and that was bad for communities.

Super-cold technology has other applications, too, like fueling rocket motors and the hydrogen bomb. And perhaps most importantly, refrigeration has also made it possible for people to become foodies, and to feel superior to people who eat canned food and Rice-A-Roni.

Blogging

You may find this hard to believe, but journalism is a business that prides itself on integrity. It's true! In the olden days, journalists researched stories, interviewed multiple credible subjects, included both sides of every story, and fact-checked every article. If you picked up a newspaper and read it cover-to-cover, you could be pretty sure that you were getting pretty true facts about everything you read.

And then, blogging happened. Now, blogging has certainly helped create a whole new world of free information. Everyone can be a reporter, no journalism school or fact-checker required. And that's the problem: We're used to believing the things we read because old-school journalism made sure that stories were true and written from balanced perspectives.

Bloggers can make stuff up if they want to and tell everyone it's the truth. There's no editor standing between them and false information, or opinion that reads like fact, so readers have to be skeptical of pretty much everything that appears on a blog. On the other hand, blogging gives voice to people who would have otherwise remained silent — and there's probably no greater tribute to the First Amendment than that. It's a brave, brave new world. Just keep your B.S. sensor calibrated.