The Untold Truth Of The Beatles

Few bands, if any, can match the Beatles' unique combination of enduring popularity and artistic credibility. But many people only know the bare-bones Beatles story: There were four of them, they were fab, they wrote amazing music, and Ringo Starr got no respect until years later. However, there's a lot more juiciness about the band you probably didn't know (and a few popular myths you should stop believing).

From a formative encounter with folk legend Bob Dylan, to their roles as civil rights activists and music video pioneers, to the surprising origins of some of their most beloved songs, here's the untold truth of the Beatles.

They started out as smoking, swearing hooligans

How do you like your Beatles? Clean-cut, mop-topped, suit-clad pop idols, or colorful, bearded hippies who revolutionized all forms of rock? Here's a third option: The early Beatles were basically punks.

As told in "The Beatles Anthology," before Brian Epstein discovered them, the Beatles played in dingy nightclubs, clad in leather jackets and jeans, and were prone to smoking and swearing onstage while eating chicken between songs. Curiously, such multitasking didn't endear them to the mainstream crowd; it seemed like the group was destined to forever play tiny clubs for barely enough money to buy more chicken.

Then, Epstein came along. He felt the group had potential, but they needed to be cleaned up. He told them to quit eating between songs and instead start bowing. He had them ditch the leather and denim for freshly tailored suits, styled their hairdos into something less messy and more fashionable, and even had them start stringing their guitars correctly. Back then, the Beatles would have excess guitar wire dangling from the tuning knobs, so when a string snapped they simply had to tie the excess string to the snapped part and keep on playing. Epstein got them to stop doing that, as wires dangling everywhere just looked messy and unprofessional. The band wasn't thrilled with Epstein's ideas initially but then concluded, as John Lennon put it, "it was a choice of making it or still eating chicken on stage." They chose wisely.

A misunderstood lyric prompted Bob Dylan to get the boys high for the first time

It's well known that the Beatles were avid smokers of marijuana; by the time they were into the more experimental phase of their recording career, one could practically catch a contact high from their music. They didn't start out that way, however, and their initiation can be traced back to one night and one man: August 28, 1964, and Bob Dylan. According to Peter Brown and Steven Gaines' "The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of The Beatles," that was the night that Dylan showed up to the Fab Four's hotel room after a gig, and while the boys' road manager Mal Evans was out securing "cheap wine" at Dylan's request, Dylan suggested that some grass was in order.

The Beatles' manager, Brian Epstein, reluctantly admitted that none of them had ever really smoked weed before, which left Dylan a bit puzzled. "But what about your song, the one about getting high?" he asked, referring to "I Wanna Hold Your Hand." This prompted John Lennon to sheepishly offer up that the lyric Dylan had in mind was not actually "I get high," but "I can't hide." Dylan, of course, was all too happy to introduce them — and before the end of the night, everyone was in stitches, and Paul McCartney was insisting that Evans follow him around with a pad and pencil to write down everything he said. Unfortunately, Evans' notes have since been lost, so we'll never know what deep thoughts McCartney might have had.

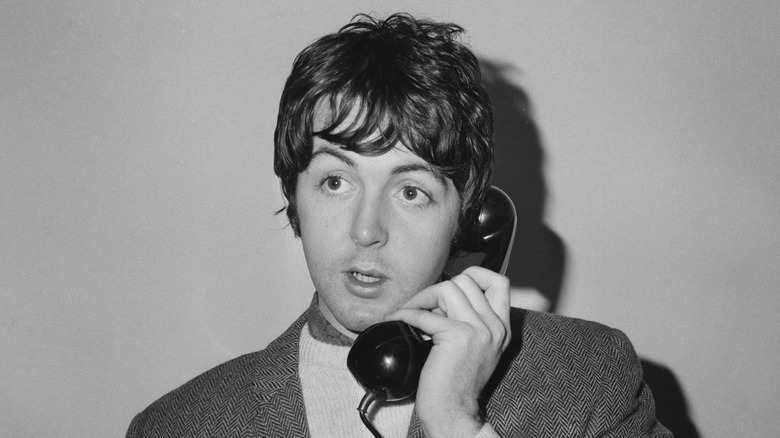

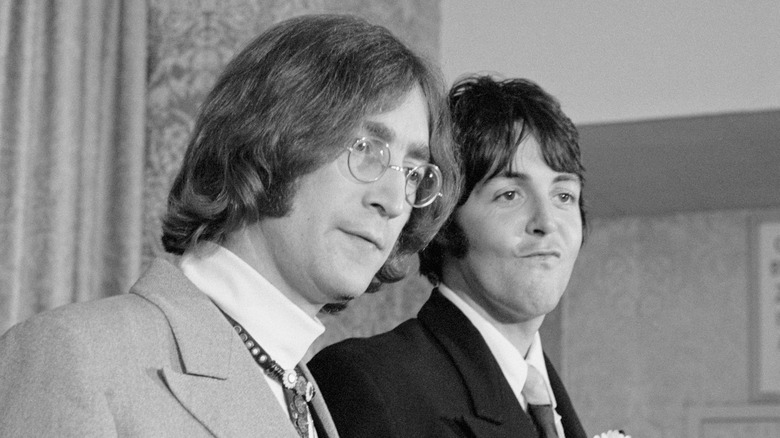

Many songs by Lennon/McCartney were only written by one of them

Most every Beatles song not written by George Harrison or Ringo Starr (which is most of them) gets credited to "Lennon/McCartney." That's due to an early agreement between the two musicians and Brian Epstein, the band's manager. Epstein and Lennon proposed that any song Lennon or McCartney wrote would be credited to "Lennon/McCartney." According to McCartney in a 2015 Esquire interview, he was initially fine with that, but suggested the credit be reversed if he were the primary (or solo) writer. Epstein and Lennon supposedly agreed, but it never happened. Ultimately, any song they wrote — including songs with one writer — got the same "Lennon/McCartney" credit.

Sometimes, McCartney seems fine with the arrangement. As he put it, "It's a good logo, like Rodgers and Hammerstein. Hammerstein and Rodgers doesn't work." Other times, he's irked by being the second guy in the name, particularly on songs like "Yesterday," which he wrote entirely by himself. Worse for him is that, in the digital era, his name often gets cut from public view. As he explains it, "You know how on your iPad there's never enough room? ... What starts to happen is, 'A song by John Lennon an-' ... So it's kind of important who comes first." McCartney also told Esquire he tried to get his alternating-credits idea going after the band broke up. Yoko allegedly said yes but then backtracked for unexplained reasons. Decades later, we're not likely to see McCartney/Lennon on anything official anytime soon.

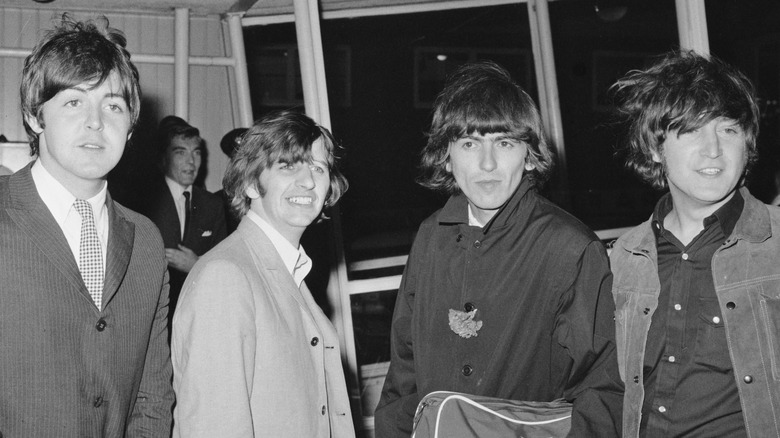

They refused to play in front of segregated audiences

During a 1964 tour of the United States, the Beatles showed up to play the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida, and were greeted with an unwelcome circumstance. The show that night was to be segregated — Black concertgoers on one side of the arena, white attendees on the other — and this simply did not fly with the band. According to the BBC, John Lennon proclaimed: "We never play to segregated audiences and we aren't going to start now. I'd sooner lose our appearance money."

As it turned out, the Beatles did play that night — after the audience was allowed to freely mingle. The experience apparently prompted them to rework their live performance contracts to specifically state that they would not play for segregated crowds, a detail confirmed by a 1965 contract for an appearance at the Cow Palace in Daly City, California, which was reported by the BBC. In a 2018 interview with GQ, McCartney described how years later, the civil rights movement in America inspired him to write one of the band's most iconic songs. "[When I wrote] Blackbird, I was sitting around with my acoustic guitar, and I'd heard about the civil rights troubles [in the United States]," he said. "It's, hopefully, a good message."

The original title for Yesterday was Scrambled Eggs

One of the most beloved Beatles songs of all time, "Yesterday" is a simple yet poignant lament for lost love and memories of a better time. But it started life with perhaps the goofiest lyrics the band ever penned. (Well, aside from "Revolution 9.")

According to Paul McCartney, the song's melody first appeared to him in a dream. He woke up, found a piano, found the chords that fit his head-tune, and had the building blocks for an all-time classic. But to ensure he didn't forget the song when more fully awake, McCartney wrote some placeholder lyrics that only someone half-asleep could devise. Calling the song "Scrambled Eggs," McCartney wrote the following Dylan-esque couplet: "Scrambled eggs / Oh my baby, how I love your legs." He apparently didn't write any egg-related words after that because he caught the giggles and couldn't continue.

"Eggs" soon became "Yesterday," and the rest is music history. But decades later, McCartney finally got around to finishing his first-draft poem. In 2013, he appeared on "Late Night With Jimmy Fallon," and the two sang a duet of the completed version of "Scrambled Eggs," complete with lines like "Waffle fries / Oh my darling, how I love your thighs / Not as much as I love waffle fries / Oh, have you tried the waffle fries?" Nothing soothes a heartbreak like comfort food.

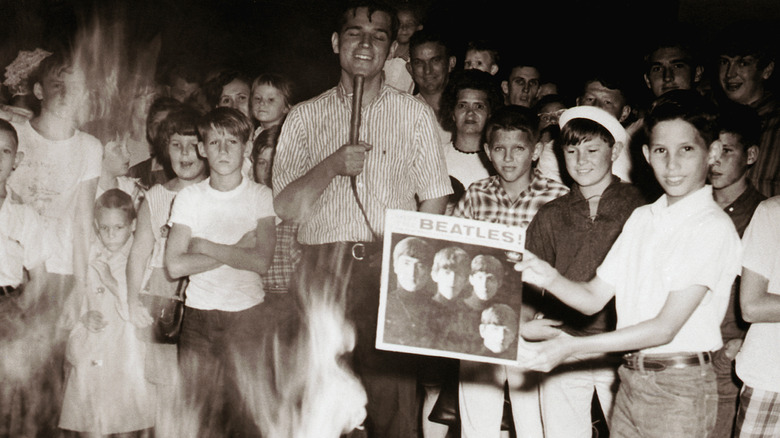

The great Beatles boycott

In March 1966, John Lennon sparked more controversy than he ever intended to. During an interview with the London Evening Standard, he claimed, "Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. ... We're more popular than Jesus now. I don't know which will go first, rock 'n' roll or Christianity." Few in England bothered to get bothered about the comment, but then it got re-published in Datebook, an American magazine for teenagers. Very quickly, according to Rolling Stone, the USA (particularly the South) went up in arms. Misinterpreting Lennon's words to assume he thought the Beatles were bigger or better than Jesus, radio stations called for Beatles boycotts, people held public record burnings (pictured above), Beatles concerts were picketed, the Vatican condemned them, and the band even started receiving death threats. At one point, members of the KKK were outright threatening Lennon's life, and the safety of the entire band came into question.

Eventually, after a cherry bomb went off during a concert and spooked the band into thinking someone shot at them, they quit touring completely. Unfortunately for Lennon, his fate might well have been sealed by that point. One of the people outraged with his statements was a born-again Christian named Mark David Chapman, once one of Lennon's biggest fans. By his own admission in a 1983 prison interview (via CNN), the Jesus comment sent him into a spiral of hatred for Lennon, one that eventually culminated in his taking Lennon's life.

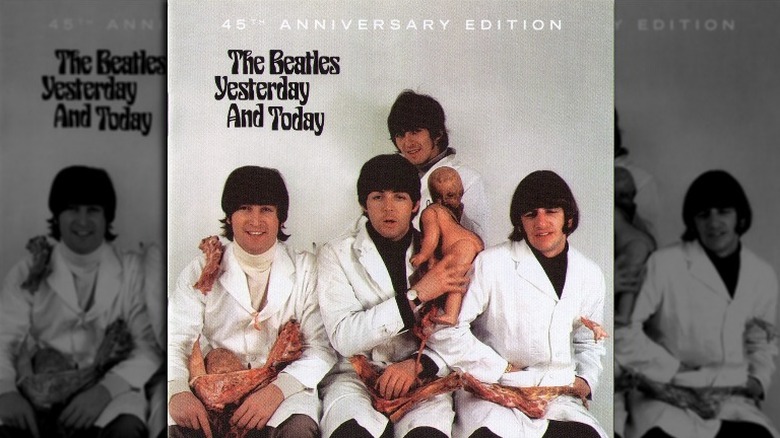

One of their album covers initially featured dead babies

The "Yesterday and Today" album cover is safe and pedestrian: The band poses around a box. But when the album first hit shelves in June 1966, it was to feature an entirely different, far more macabre cover of the Fab Four posing with dead babies (above). They were just doll parts, but it still makes one wonder why you'd even try such a stunt. Well, according to Rolling Stone, it's because one of the band's favorite photographers, Robert Whitaker, wanted to do something different. As he explained, "I got fed up with taking squeaky-clean pictures of the Beatles, and I thought I'd revolutionize what pop idols are." Huh.

Most of the Beatles were down for it, with Paul McCartney deadpanning to the label president that it was their comment on the Vietnam War. But ultimately, a wide release of the cover didn't happen, for the same reason behind most things in life: money. The Beatles were negotiating a new record deal and didn't want to alienate any potential suitors. So they okayed the new, inoffensive cover. But many of the dead-baby covers still exist.

Capitol sent out thousands of advance copies to record stores and promotional outlets, and quite a few were sold before Capitol recalled them, choosing to save money by simply pasting the new cover over the old one. If a fan in the know steamed off the new cover, they would be rewarded with dead babies, an absolutely terrible phrase in literally any other context.

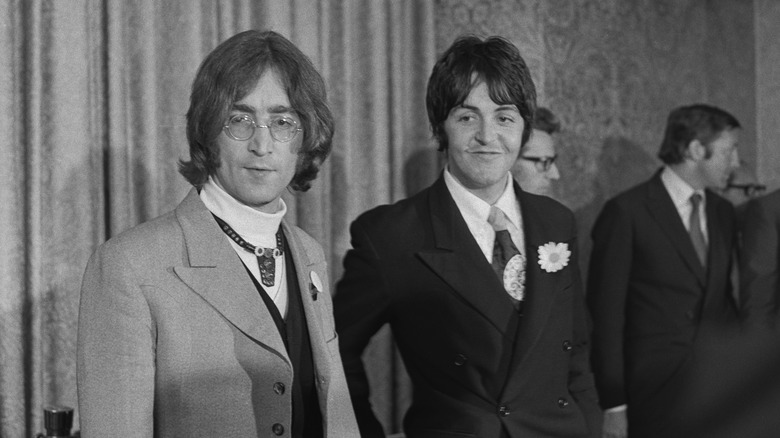

They didn't break up because of Yoko

Since the Beatles broke up, people have faulted Lennon's widow, Yoko Ono. To them, things were copacetic in the band, then she showed up and convinced him he was better than the band, he listened, and the two went off to record weird music together. It got to the point where (as explained by TV Tropes) anytime a girl threatens to come between a band, cast, or team, she's the "Yoko."

Except, it's just not true. The Beatles were almost certainly going to break up anyway, and anyone who blames Yoko is simply angry at the wrong target. That's not us saying it — Paul McCartney himself has argued as much. In a 2012 interview with Al Jazeera's English network, McCartney straight-up said, "She certainly didn't break the group up. I don't think you can blame her for anything." In his mind, Lennon was ready to leave anyway, having grown tired (according to Fox News) of the "unhealthy rivalry" between the band members — particularly between himself and McCartney — and wanted to move on. As far as McCartney is concerned, all Yoko did was provide Lennon with the courage and inspiration to leave, and to embrace his own creativity full-throttle.

As for why people continue to blame Yoko decades after the breakup? In the mind of Billboard editor Joe Levy, it's because they "[can't] accept, as ... Lennon put it on his first solo album, that the dream was over." Sadly, it's much easier to blame someone than accept that nothing lasts forever.

A 'wicked dentist' introduced them to LSD

The Beatles are closely associated with LSD, whether "Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" is about the drug or not. But the group first encountered LSD not by experimenting with it at a party or being introduced to it by a fellow rock star. Nope, they first did it because of a dentist.

As the band recounted in "The Beatles Anthology," in 1965 John Lennon, George Harrison, and both of their girlfriends were having dinner with a friend Harrison called a "wicked dentist." Without their knowledge or consent, the dentist slipped LSD into their coffee. Harrison felt the dentist had sexual adventures in mind and wanted them all in the right mood for an orgy. But they had places to go and skipped out. Later, they started feeling the drug's effects — as Harrison put it, "suddenly I felt ... a very concentrated version of the best feeling I'd ever had in my whole life. ... I felt in love, not with anything or anybody in particular, but with everything. Everything was perfect, in a perfect light, and I had an overwhelming desire to go round the club telling everybody how much I loved them — people I'd never seen before." Later, on the drive home, Lennon recalled freaking out over a red light they thought was a fire, and Harrison remembered "really concentrating" on driving 18 miles per hour. Once home, Lennon decided that Harrison's home was a submarine, and he was piloting it. No word on whether the submarine was yellow, but probably.

'Get Back' originally made fun of xenophobia

The ever-popular "Get Back," one of the Beatles final hits before their 1970 breakup, is mostly a fun song about hippies and the counterculture. But during the writing phase, it was about something very different and the words were much harsher. "Get Back" was once a scathing satire of xenophobia.

Informally dubbed "No Pakistanis" by fans, the original "Get Back" lyrics featured lines like "Who is that Black man? Don't dig no Pakistanis taking all the people's jobs," which gives the familiar "Get back to where you once belonged" chorus a way darker edge. According to Salon, the song was meant to satirize anti-immigration sentiments, but there's honestly little to suggest that. Taken at face value, it does seem like a sincere "no immigrants" song, so it's probably best that the group never completed or released it. ("No Pakistanis" didn't even make the six-CD "Beatles Anthology" set.) The band rarely talks about the shelved words, though Paul McCartney did in 1986, making it clear the song was a satire and that all you need to do is observe the Beatles' past to confirm that. As he said, "If there was any group that was not racist, it was the Beatles. I mean, all our favorite people were always Black." That said, don't expect — especially in today's super-turbulent climate — McCartney to trot the song out for concertgoers anytime soon, or ever.

Happiness is a Warm Gun was inspired by a gun magazine

During the Beatles' later years, John Lennon was extremely fond of ... well, rather opaque lyrics that were open to all manner of interpretation. Other than "I Am the Walrus," there is probably no better example of this than "Happiness Is a Warm Gun," from 1968's "The Beatles," also known as the White Album. Apparently, many fans have assumed the song to be about drugs, particularly heroin (likely due to the lyric "When I hold you in my arms / And I feel my finger on your trigger / I know nobody can do me no harm"), as Lennon has refuted this notion on multiple occasions. Instead, he asserted that the tune's inspiration was much more straightforward: It came from a magazine for gun enthusiasts.

According to "A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song" by Steve Turner, producer George Martin had brought the magazine to the studio during the recording of "The Beatles," and on the cover was the phrase, "Happiness Is a Warm Gun in Your Hand." Lennon remarked, "I thought, what a fantastic thing to say ... A warm gun means you've just shot something." Lennon repeated the story in a September 1980 interview with Playboy magazine (via Beatles Interviews), and reiterated that no, the song was not about heroin — but that the idea of a "warm gun" as a sexual pun just might have crossed his mind.

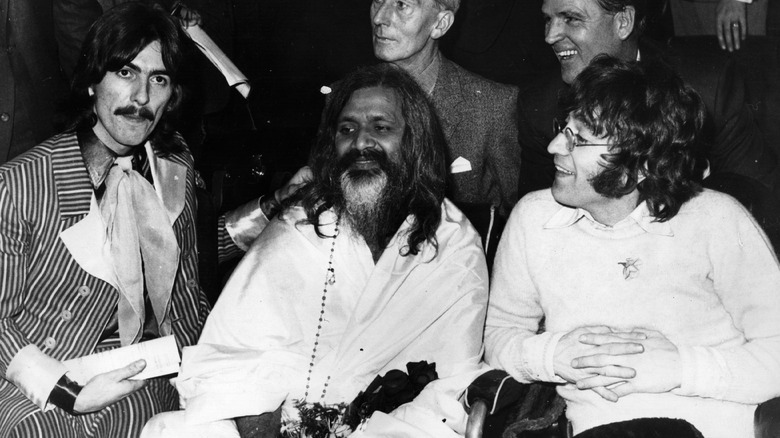

Their trip to India yielded a ton of classic songs

In 1968, after dropping the stone cold masterpiece "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band" the previous year, the Beatles took an odd and highly publicized vacation of sorts: to Rishikesh, India, to study transcendental meditation under Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who was key to popularizing the practice in the Western world. A number of other celebrities were present on the retreat, including fellow pop star Donovan, the Beach Boys' Mike Love, and actress Mia Farrow — and while the boys took advantage of the opportunity to socialize, they also used the retreat as something of a songwriting workshop (via Far Out Magazine).

The band members stayed for varying lengths of time; Ringo Starr left after a week and a half, Paul McCartney took off not long after, and John Lennon and George Harrison stuck it out for about two months. But while in India, all the boys were struck by inspiration, penning tunes that would appear on 1968's "The Beatles" double album and 1969's "Abbey Road," with some stragglers later appearing on solo albums. Among these songs: "Revolution," "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da," "I'm So Tired," "Rocky Raccoon," "Blackbird," "The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill," "Back in the U.S.S.R.," and the lovely "Dear Prudence," which was inspired by Mia Farrow's traumatized, reclusive sister. Even Ringo got into the act, penning the country-flavored "Don't Pass Me By," which was his first solo composition to make its way onto a Beatles album.

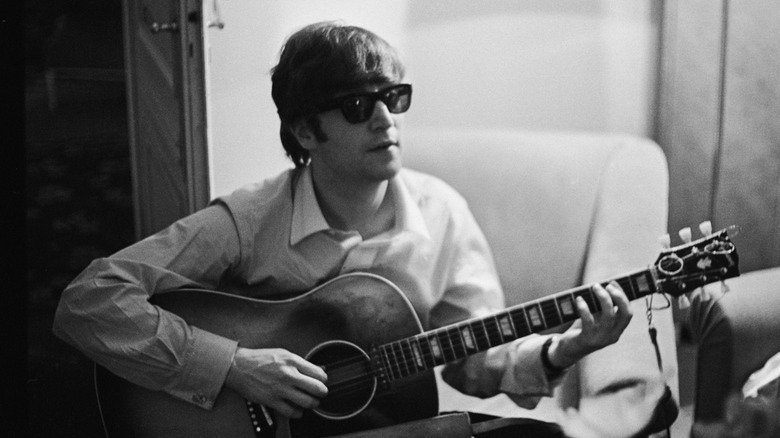

Lennon wrote I Am the Walrus to screw with people

The Beatles' lyrics were unlike most any other pop music of the time, but that doesn't mean they were intentionally writing profound poetry. Case in point: "I Am the Walrus," perhaps the most lyrically obtuse Beatles song of them all. Why is yellow custard dripping from a dead dog's eye? Why would anyone sit on a cornflake? Was the walrus John or Paul? Is a crabalocker fishwife worth marrying? As it turns out, it's almost completely gibberish, put out by John Lennon as a poke at people taking his pop music too seriously.

According to The Beatles Bible, Lennon was working on "Walrus" when he received a letter from a student at his old school, Quarry Bank. In the letter, the student told Lennon that his teacher was having them read Beatles lyrics and analyze them for deeper meaning. Lennon was, as you might expect, deeply amused by the idea, and to mess with this teacher, he decided to take the absurdity of "Walrus" completely over the top. He asked a childhood friend to recall a playground chant they used to sing — he then warped that into the completely meaningless "Yellow matter custard / Dripping from a dead dog's eye" verse, turned to his friend, and cracked, "Let the f****rs work that one out." And to this day, people still try, despite the only real meaning being "John Lennon is a big silly."

None of them could read or write music

It's not hyperbole to say that the Beatles are among the most influential musicians of the 20th century, or even of all time. Their songwriting, lyricism, and musicianship has been the subject of endless critical analysis, and has been emulated by countless artists in their wake; their creativity pushed the boundaries of recording technology, leading to the emergence of techniques that had never been conceived of before, but which have since become commonplace. If one were so inclined, one could find a wealth of university courses on the band and their influence — which makes it all the more shocking that not a single one of them could actually read or write music.

This was disclosed by John Lennon in his 1980 interview with Playboy (via Beatles Interviews), when he was asked his opinion of Ringo Starr's musicianship. Lennon praised the musical contributions of Starr, calling him a "damn good drummer" before adding the qualifier that none of the band members were technical geniuses on their instruments. "None of us are technical musicians. None of us could read music. None of us can write it," he said. "But as pure musicians, as inspired humans to make the noise, [Paul McCartney and Starr] are as good as anybody." In a 2018 interview with 60 Minutes, McCartney confirmed this. "I don't read music or write music. None of us did in the Beatles," he said. "We did some good stuff though. But none of it was written down by us."

They were music video pioneers

The Beatles famously stopped touring at the height of their popularity in 1966, allowing them to focus solely on writing and recording. There was, however, still a demand for them to appear on television to promote those recordings, a duty which they were none too fond of. Speaking with The New York Times in 2015, Ringo Starr described the solution to this problem. "We did come to the solid thought, well, we can't be everywhere," he said, "so we made these little movies and sent them out."

These "little movies" were then known as promotional films, but today, they would be recognized as music videos — a form that it's fair to say the Beatles helped to pioneer. Many of their early clips, such as the shorts for "Help!" and "I Feel Fine," were exceedingly simple (and those two, in fact, were among 10 that were shot in a single day). Later, though, the Beatles' promo films would come to match the artistry of their music. In particular, the clips for "Penny Lane" and "Strawberry Fields Forever" — shot just days apart, and utilizing many of the same locations — were wildly innovative for their time. After a frenetic editing period of just under two weeks, both clips were shown on the iconic British program "Top of the Pops" on February 15, 1967 — showcasing the music video form well over a decade before MTV would launch it into the popular consciousness.

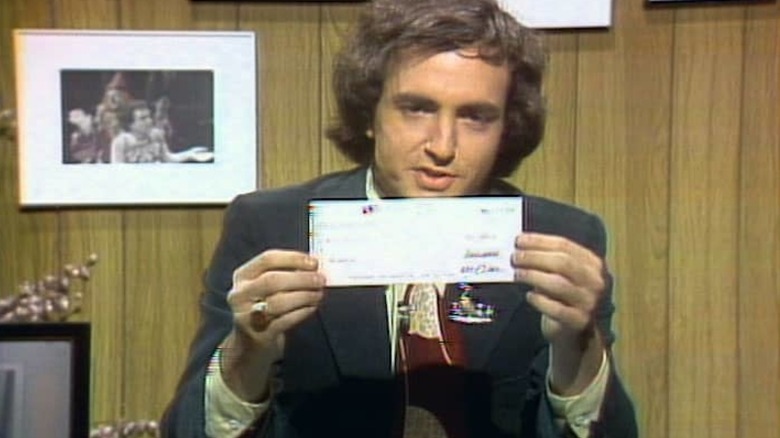

Lennon and McCartney almost reunited on Saturday Night Live

Approximately one second after the Beatles broke up, the public began clamoring for a Beatles reunion. Amazingly, we almost got just that on April 24, 1976, and it would've taken place on "Saturday Night Live," of all places.

During that evening's episode, "SNL" producer Lorne Michaels appeared on-camera to offer the Beatles a comically low $3,000 to reunite on his show and sing a paltry three songs. Obviously, he had no reason to believe the group would actually take him up on the offer, but it almost happened. As it turns out, John Lennon and Paul McCartney were in New York City, hanging out and watching the show together. As Lennon recounted in the book "All We Are Saying" by David Sheff, the pair actually considered taking a cab down to the studio and accepting Michaels' offer, just to be funny.

Ultimately they chose not to, but not because they decided the money wasn't right or because they felt it would be detrimental to their legacy to reunite on a comedy show. Rather, they stayed put because, as Lennon put it, "we were actually too tired." That's right — had SNL aired that sketch earlier in the show, John and Paul might've had enough spring in their step to stage the most sought-after reunion in rock history, for about as much as it cost to buy a brand-new 1976 Plymouth Arrow.

There was more than one 'fifth Beatle'

The Fab Four may generally be considered a self-contained unit, but this was not necessarily the case. Sure, they occasionally employed studio musicians like everyone else to play all horns, strings, and the like, but there were a couple of individuals in particular who contributed to the band to such an extent that they might have been considered an actual member. First and foremost among those: producer George Martin, whose contributions went beyond indulging the boys' more unconventional ideas by way of wild studio experimentation. Martin actually played piano, celeste, and organ on a number of recordings, arranged the orchestral elements of tunes such as "Yesterday," and arranged vocal harmonies on songs like "Here, There, and Everywhere."

Any discussion about a so-called "fifth Beatle," though, wouldn't be complete without mentioning American singer, songwriter, and keyboardist Billy Preston (pictured above), who played an integral role in the recording of the Beatles' final released album, "Let It Be." Preston had been an acquaintance of the band since their Hamburg days, and he was invited to sit in during the album's recording by George Harrison at a time during which Harrison wasn't sure whether he wanted to continue. Preston was described by his former manager Joyce Moore as the "glue and glitter" that held the band together during this period (via CBC), and for his contribution, he became the only outside musician to ever receive credit on the liner notes of a Beatles album.

The Beatles songs that no Beatles played on

When it appeared as the second track on the Beatles' 1966 album "Revolver," the dramatic, heartbreaking tune "Eleanor Rigby" marked the band's starkest departure yet from their usual repertoire of poppy love songs. The tale of a lonely old woman who dies alone and is "buried along with her name," the Paul McCartney-penned song, with its sorrowful melody and wrenching string instrumentation, has to be mentioned among the saddest pieces of popular music ever written. It is also a very curious outlier among the band's discography, in that not a single Beatle actually played an instrument on it.

For the track, producer George Martin enlisted two quartets of string musicians, and took the lead in arranging the parts they would play. If the foreboding, eerie instrumentation is slightly reminiscent of the great composer Bernard Herrmann, well, that is no accident; Martin has said that he was influenced by Herrmann's score for the 1966 Ray Bradbury adaptation "Fahrenheit 451." George Harrison and John Lennon sang backup on the tune, complementing Paul McCartney's plaintive lead vocal; Ringo Starr sat the recording out completely. Perhaps to make up for this, "Eleanor Rigby" was released as a double A-side single backed by a song with a Starr lead vocal — "Yellow Submarine," thereby creating the most bizarre tonal clash in the history of the double A-side.

The group would make a few more songs in the coming years that saw them only contribute vocals, including "Good Night," "She's Leaving Home," and "The Inner Light."

A Paul-less Beatles song

"Eleanor Rigby" and the others were far from the only tunes missing any instrumental contribution from a member of the Beatles. John Lennon was known to sit out songs on a fairly regular basis, and Paul McCartney played drums on a few tunes in Ringo Starr's absence, including "Back in the U.S.S.R." and "The Ballad of John and Yoko." But in the band's entire catalog, there was only one solitary tune that McCartney refused to play on: "She Said, She Said," from the "Revolver" album.

According to the Paul McCartney biography "Many Years From Now," the song has its origins in a 1965 party at a house the Beatles were parked in during their American tour that year. Also present at the party was actor Peter Fonda, who was attempting to comfort an LSD-tripping George Harrison. When Harrison remarked that he felt like he was dying, Fonda — who had had a near-death experience of sorts during a childhood illness — told him not to worry, saying "I know what it's like to be dead." The remark annoyed John Lennon, but it evidently stuck with him, as he eventually used it as a key lyric in "She Said, She Said." Said McCartney of the song, "I think it was one of the only Beatle records I never played on. I think we'd had a [fight] or something ... [and] George played bass."

Lennon and McCartney jammed together post-Beatles

The relationship between Paul McCartney and John Lennon was famously contentious, but as it turns out, the two did have a brief reunion of sorts years after the Beatles broke up. This happened during Lennon's infamous "Lost Weekend," during which he just sort of hung out in New York City and LA with his assistant, May Pang, for about a year and a half, apart from Yoko Ono. He spent much of this time drinking, doing drugs, carousing with Harry Nilsson, and occasionally recording some music — and one night in 1974, he happened to run into his old bandmate at a studio in Burbank.

Per Far Out Magazine, there happened to be a few other musicians present that night, among them session guitarist Jesse Ed Davis, guitarist and former Beatles road manager Ed Freeman, and saxophonist Bobby Keys. Oh, and also the legendarily talented Nilsson, and some dude by the name of Stevie Wonder. The resulting sessions should have been unbelievably epic — but, perhaps as a result of all the cocaine that was flying around the studio, they ended up being the exact opposite of that. The chaotic, messy, and downright boring bootleg recording has come to be known as "A Toot and a Snore in '74," in reference to... well, the coke and the boredom.