Landmark Cases That Could Change By The Overturning Of Roe V. Wade

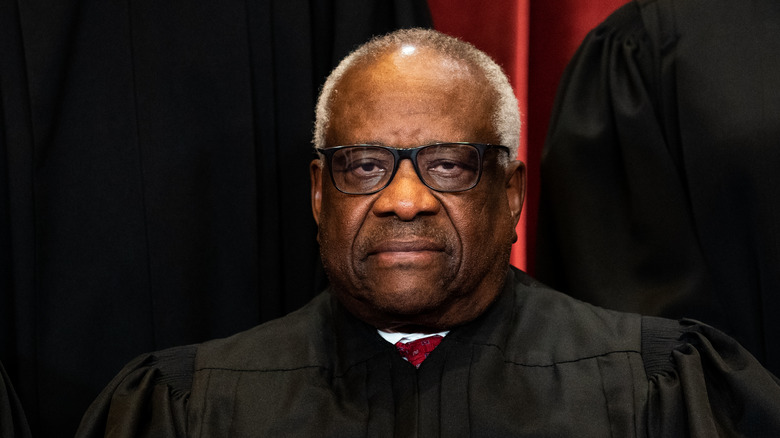

Roe v. Wade's repeal has inflamed passions across the country as pro-choice activists mobilize to defend what they see as a constitutional right, while pro-life advocates move to restrict abortion at the state level. But the decision has some worried that other rights could be next, because buried in the concurring opinion of Justice Clarence Thomas to Dobbs v. Jackson was a suggestion that SCOTUS revisit a series of decisions pertaining to contraceptive bans, bans on homosexual intimacy, and same-sex marriage.

The cases in question are Griswold v. Connecticut, Lawrence v. Texas, and Obergefell v. Hodges, which the court used to enshrine a number of rights that Americans take as given today. But Thomas' opinion suggests that all of these cases — like Roe — were wrongly decided using judicial overreach and a principle called substantive due process, contradicting previous courts that upheld the appellants on 14th Amendment grounds.

So what exactly do these terms mean, and is there any possibility that these cases will be overturned? Here are how and why the justices on the SCOTUS majority concluded their opinions in all three cases, how the dissent argued against the decisions, and what consequences repeal would have in the lives of ordinary Americans.

Griswold v. Connecticut

The Griswold v. Connecticut case (via the Library of Congress) surfaced when a number of Planned Parenthood employees were convicted on two main charges of providing a married couple with advice on contraceptives and a prescription for a contraceptive device, which ran afoul of a Connecticut ban on contraception that punished violators with a fine and at least two months in prison. The convicted staff appealed their convictions all the way to the Supreme Court in 1965, which struck down contraceptive bans in Connecticut and across the United States.

The 1965 court ruled that a number of constitutional violations were present. The first was on First Amendment grounds. Convicting doctors for advising patients on birth control was an infringement on the doctors' freedom of speech, which the court extended to distribution, reception, and reading of information in a lawful assembly (meeting with patients). The second entailed privacy. The majority opinion found that the Connecticut law sought to achieve its goals by having a harmful impact on marriages and inserting itself into private sex lives.

Justice Orville Douglas wrote that Connecticut could not legislate married couples' private sex lives. "Would we allow the police to search the sacred precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of contraceptives?" Any unlawful searches in homes to enforce the law would be Fourth Amendment violations against unlawful searches. But the justices extended the Fourth Amendment to entail a fundamental right to privacy. Thus states could not pass laws to abridge this right, as that would be a violation of the 14th Amendment's due process clause.

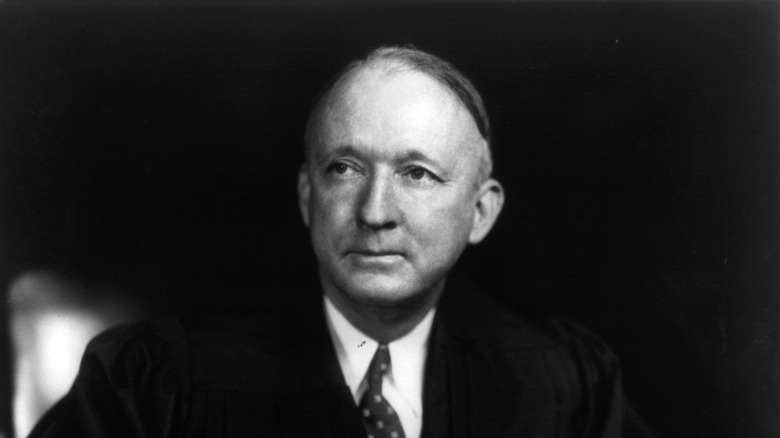

Justice Hugo Black's dissent

The major issue at hand in the Griswold case was privacy, which critics argued was elevated to a fundamental right well outside its Fourth Amendment bounds. Now, in the dissent, justices Hugo Black and Potter Stewart opposed the Connecticut law and supported the doctors' right to give contraceptive advice to their patients (via the Library of Congress). However, Black also noted that they had willingly contravened what they viewed as a constitutional Connecticut law.

Black argued that the Fourth Amendment did not confer a blanket right to privacy –- it only protected against unlawful searches and seizures. So although police could not enforce Connecticut law by breaking into people's bedrooms, the law itself was not unconstitutional. Instead, Black and Stewart accused their colleagues of legislating from the bench according to their "sense of fairness and justice" rather than the text of the Constitution. SCOTUS, he worried, had become a legislative body like Congress rather than a purely interpretive body that told Americans what the law was.

According to Black, SCOTUS had created a vague concept called the "right to privacy." This would be abused to read new rights into the U.S. Constitution that were not explicitly enumerated. As far as he was aware, the government had the right to invade privacy unless it was explicitly forbidden under a clearly delineated constitutional statute such as the Fourth Amendment. Since the Griswold ruling, both Lawrence v. Texas and Obergefell v. Hodges hinged in part or entirely on the right to privacy, which has become controversial in the 21st century.

Can contraceptives be banned again?

On one hand, as the American Bar Association notes, the Griswold case was considered a triumph of civil rights over state intrusion into private affairs that would become the bedrock of a host of other decisions including Roe v. Wade and subsequent "culture war" rulings. As WNET 13 details, SCOTUS ruled that since a fundamental constitutional right to marital privacy existed, states could not legislate against it, since the Constitution trumps state law. That said, there has been little desire to challenge the legality of contraception. Enforcing such laws would seem impossible given that nearly three-quarters of American women use some form of birth control (via CDC).

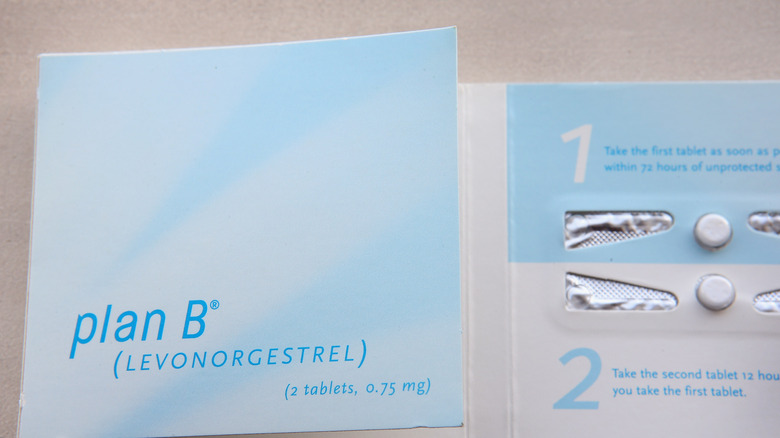

All that said, Griswold is a possible candidate to go before SCOTUS because it is inextricably linked to the Dobbs v. Jackson ruling overturning Roe v. Wade. As noted in Pew, states with restrictions on abortion have also sought bans on contraceptives that can also function as abortifacients if fertilization occurs (like Plan B and IUDs). Since bills such as Louisiana's 813 defines fertilization as the beginning of personhood, the bill's logic follows that use of Plan B, for instance, constitutes the performance of an abortion. But opponents of such bills would argue that Griswold protects these contraceptives, creating a complex set of circumstances that could result in a challenge.

If Griswold were fully overturned, it would give states the power to decide whether to allow it and what types would fall under respective definitions of contraception, as per Salon. But it would be a heavily polarizing case that would raise a handful of enforcement issues.

Lawrence v. Texas

In 2003, two men engaged in consensual sex were arrested under Texas anti-sodomy laws that forbade same-sex activities following a police raid on the residence. They appealed their case to the Supreme Court, which ruled 6-3 in Lawrence v. Texas that the statute they were convicted under was unconstitutional.

As noted in the majority opinion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the court did not use the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause as the petitioners had initially argued. Instead, it argued that sodomy laws were not intended to target gays historically, being used instead to punish non-procreative sex acts involving minors and coercion, among others. Because of the high burden of proof, they were rarely prosecuted except in the aforementioned cases.

The bulk of the ruling, however, was grounded in Griswold v. Connecticut and subsequent cases such as Roe v. Wade. Griswold ruled that married couples had the right to conduct private, consensual sexual relations as long as they did not harm the general public or a third party. If this was the case, then same-sex couples had the same rights behind bedroom doors as long as they did not violate other statutes (like age of consent or decency laws). If the appellants' actions were protected under a constitutional right to the liberty to live their lives according to their identities, then any state attempt to abridge them without any compelling interest ran afoul of the due process clause of the 14th Amendment, which guaranteed their right to liberty and protected them from state infringement on their privacy.

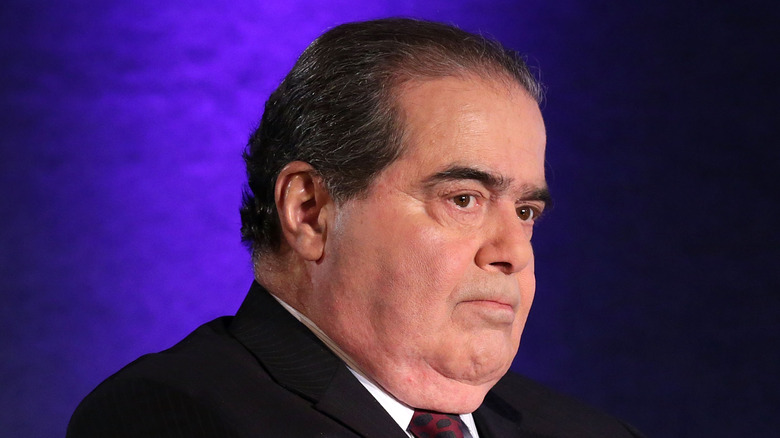

Antonin Scalia's objections

In the dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia argued that the decision resulted from an incorrect reading of the 14th Amendment. The justice argued that the activities proscribed in the Texas statute were not "fundamental rights" subject to 14th Amendment protections. Since homosexual conduct was not "deeply rooted" in American legal history and tradition and often reviled, Scalia wrote that one could not simply read this as a right under the 14th Amendment's guarantee of liberty.

To support his view, Scalia noted that states frequently made laws restricting personal liberty when there was an overriding state interest. He said no one ever argued that prostitution and heroin use were fundamental rights, and therefore, states could restrict them at the expense of critics' liberty to engage in such practices. Since the court had previously ruled that public decency laws and other statutes relating to morality were permitted, Scalia argued that the Texas law was no different. In a caveat, the justice also mentioned that he understood the desires of gays to be accepted without discrimination but warned that this was best done through societal outreach rather than forcing it through courts on a state where the majority of the population opposed any changes to state morality laws.

Will Ken Paxton try to overturn Lawrence?

There has been relatively little discussion about the implications of overturning Lawrence v. Texas until now because Dobbs v. Jackson referenced it a number of times both in the dissent and majority opinions. If it were overturned, then one can only assume that states would be free to legislate sexual behavior once again. But there does not seem to be much interest in touching the Lawrence ruling even from the Supreme Court's conservative majority.

In the majority opinion for Dobbs v. Jackson, Justice Samuel Alito wrote that fears of overturning Lawrence v. Texas were unfounded, accusing the dissenting justices of using the repeal of Roe v. Wade to stoke the fear that perhaps cases like Lawrence would be next. However, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton told News Nation (via Twitter) that he is willing to defend the Texas law in a challenge to Lawrence (assuming it makes it to SCOTUS).

Paxton has a powerful sympathizer in Justice Clarence Thomas, who in his concurring opinion wrote that Lawrence should be revisited alongside Griswold and Obergefell v. Hodges, the decision that legalized same-sex marriage nationwide.

Obergefell v. Hodges

Obergefell v. Hodges is popularly known as the same-sex marriage ruling. When a number of same-sex couples sought to register their marriages in states where the institution was defined as a union between one man and one woman, the court took the side of the couples and ruled that states had to register same-sex marriages that were legally performed in other states.

The majority opinion written by Justice Anthony Kennedy leaned principally –- like the previous cases -– on the 14th Amendment's rights to liberty and equal protection. Kennedy wrote that the 14th Amendment's right to liberty extended to the right to make one's own autonomous lifestyle choices (within the law) that were in line with "personal identity and beliefs," similar wording to that of the Lawrence v. Texas case. History and tradition, the justice argued, could guide American law but could not limit it in changing times as new issues cropped up and morality evolved –- especially when children of same-sex couples were involved.

Having set up a background, the real meat of the opinion is based upon the 1967 ruling in Loving v. Virginia. This famous case struck down state bans on interracial marriage. Kennedy wrote that this ruling had established the right to marry as a fundamental right. If marriage was indeed a fundamental right, then the states could not deny it to adults on the basis of sex -– a violation of the 14th Amendment per the majority opinion.

The conservative indictment of the ruling

The dissents in Obergefell v. Hodges from justices John Roberts, Antonin Scalia, and Samuel Alito were fairly similar in all but tone. They argued that the court could not compel states to alter their definitions of marriage because the Constitution did not explicitly define marriage. Lacking an explicit definition, it was under state purview. They further rejected any parallel to Loving v. Virginia because the latter case affirmed the right of men and women of different races to marry without altering the institution's definition. Alito further accused the majority of engaging in moral blackmail by painting opponents of Obergefell as racists and bigots. Scalia's principal opposition was to a "naked judicial claim to ... super-legislative power" by SCOTUS in violation of the Ninth and 10th amendments that delegate certain powers to Washington and others to the states and the American people.

Justice Clarence Thomas' dissent, however, stands out from the rest. Thomas invoked the purpose of the Constitution against the ruling. The Constitution, Thomas wrote, was designed to protect states from federal power and allow them to regulate their own affairs beyond the fundamental rights enumerated therein. In legislating same-sex marriage, Thomas argued that SCOTUS had flipped the Constitution on its head, allowing the petitioners to undercut the state-level democratic processes because they disliked the outcome. Instead of interpreting the law in the context of fundamental rights enumerated in the Constitution relating to life, liberty, and property, the majority -– Thomas held — had transformed liberty into a vague term through "substantive due process," the central issue that influenced the decision in all of these cases.

Back to the states?

At the moment, Obergefell v. Hodges seems safe. But in the case of repeal, the result would be similar to the aftermath of Roe v. Wade -– namely that the issue of same-sex marriage reverts to the states. In 11 states and Washington, D.C., which passed it democratically or legislatively, nothing will change. But according to Britannica's Pro-Con, 13 states have laws that ban same-sex marriage on the books that are currently unenforceable due to the Obergefell ruling. Eight of them were embroiled in legal battles when SCOTUS ruled in 2015. If Obergefell were repealed, some of these laws could likely reactivate in absence of federal mandates.

In the case of repeal, popular opinion would likely guide individual states, but sentiments are unclear. Gallup found that 71% of Americans support recognition of same-sex unions. LGBTQ+ advocacy organization GLAAD, however, found in 2019 that the percentage of 18-34 voters who are "very or somewhat comfortable" with LGBTQ+ issues and people has steeply dropped to 45% from 53%, particularly in personal situations. GLAAD also found a high support for same-sex marriage though, so an explanation for this divergence will help shed light on a possible post-Obergefell America.

Given the numbers, states that decide to legalize same-sex marriage will probably have to compromise. Religious institutions and businesses will likely want an explicit conscience exemption that protects the exercise of religious beliefs, as per Rolling Stone, when it comes to facilities access, participation in same-sex weddings, and the issuing of marriage licenses.

The controversy of substantive due process

These three cases all have one thing in common: They all rest on the legal principle of "substantive due process. " According to Cornell University's Legal Information Institute, the principle holds that courts can establish and protect unenumerated rights in the U.S. Constitution that they hold to exist under a "penumbra" of the first eight amendments and are protected by the Fifth and 14th amendments. The existence of these rights is inferred from the text of the Constitution along with American history and tradition. But therein lies the problem: How far can one read beyond the letter of the law?

Justice Clarence Thomas roundly criticized substantive due process in Dobbs v. Jackson. Thomas argued first that even if one accepts substantive due process, abortion is not one of them because it is not rooted in American history or tradition. Now, if he had stopped there -– as the other justices did -– then the potential for the other aforementioned cases to stand is unaffected. But Thomas further argues that the entire concept of substantive due process is erroneous.

Thomas' main gripe with substantive due process is that it has, as far as he sees it, created "privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States" that do not exist in the text of the Constitution and are the creation of individual judges. Thus, the aforementioned rulings, which Thomas held do not pertain to rights explicitly mentioned in the Constitution (and therefore are not protected under the 14the Amendment's due process clause), are potentially erroneous and should be revisited in future SCOTUS cases.

What did the majority say?

Justice Clarence Thomas' call to revisit the previous cases in Dobbs v. Jackson has swept the media, causing public outcry from pro-choice advocates. However, the likelihood of repeal, per the other justices' own words, isn't currently on the table. Thomas' opinion is his alone. No other justice joined his concurrence. Instead, the majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito cast Roe v. Wade as a unique case because it dealt with the problem of "fetal life."

In the majority opinion, Alito noted that pro-choice advocates cast Roe v. Wade in the same light as cases related to sexual/marital privacy and equal protection under the law, like Griswold and the others. But the court countered that Roe was different. It contained the added complication because abortion –- per Roe and Casey themselves, ended "fetal life." Substituting "fetal life" with "unborn human bing," as the Mississippi Gestational Age Act did, created a conundrum over the status of life's beginning that the Supreme Court did not have the purview to decide, per Alito. The other rulings, in contrast, only concerned matters between consenting adults. Thus, the court found that Roe v. Wade could not be supported with or be used to support any of the other rulings. This, however, is good news for supporters of Griswold, Obergefell, and Lawrence, since it also means that the justices have rendered Roe's repeal irrelevant to them.

Loving v. Virginia

Lately, media outlets such as Business Insider have cited legal experts claiming that the Roe ruling endangers not only the aforementioned cases but also the landmark 1967 Loving v. Virginia decision that struck down interracial marriage bans, arguing that American's right to privacy is at stake. But Akhil Amar of Yale has argued that Roe v. Wade is incomparable to Loving or the other cases. In the Wall Street Journal, Amar proposed measuring whether a purported right was deeply rooted in American legal history and tradition –- the major lynchpin for overturning Roe through its popularity.

Applied to Loving, Amar noted that less than two-thirds of the country permitted interracial marriages at the time while several others allowed them to be registered (but not performed). Although not always part of the American tradition, interracial marriage has since planted deep roots in American society, and few oppose it today. Obergefell v. Hodges and same-sex marriage pass the test too with broad public support. Griswold passes too because Connecticut's unique ban on contraceptives suggested that American tradition opposed legislating such an intimate matter.

Ultimately, Amar appears to advocate for dialogue and letting the democratic process run its course. If it means that some states will ban abortion in Roe's aftermath, then so be it. But a fiercely debated issue such as abortion where there is no clear consensus, he writes, cannot be compared to issues that Americans increasingly agree on. At least from his perspective, he makes a strong argument that the decisions Thomas mentioned are too ingrained in American society to be changing anytime soon.