The Tragic Story Of The Last Known Person To Die From Smallpox

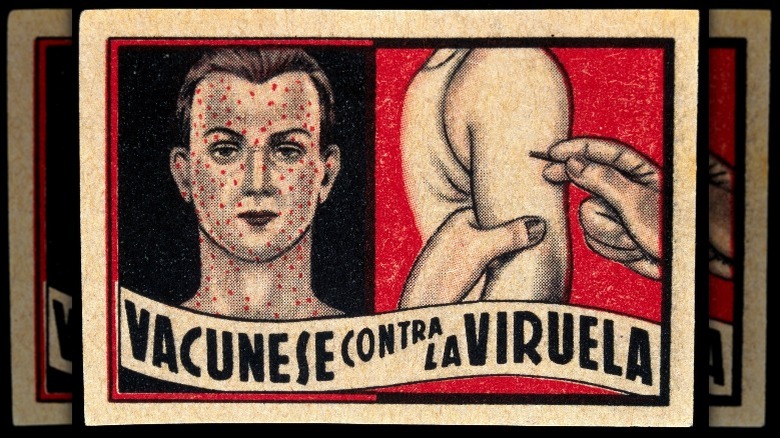

Today, smallpox is all but forgotten, though you may know someone from an older generation with a telltale scar. According to History, that mark was left behind on someone's arm after they were vaccinated against the virus. The vaccination site would turn into a scab that would then fall off, leaving behind a distinct round scar.

Getting people on board with a vaccination program in general can be tough, much less one that leaves behind a permanent mark. Yet smallpox is no ordinary, inconvenient chickenpox or influenza virus. For many centuries, it utterly ravaged human populations. The most common form of the virus, variola major, had a devastating mortality rate of 30%, according to the World Health Organization. By contrast, the COVID-19 mortality rate in the United States, where more than a million people have died of the disease, barely breaks 1% (via Johns Hopkins).

Thanks to a massive worldwide campaign, smallpox is now a thing of the past. But just before it was officially declared eradicated in 1980, things were far from certain. In a haunting turn, the virus took the life of one healthy woman in 1970s England, surprising researchers and doctors just when they thought the virus had finally retreated. Here's the tragic story of the last known person to die from smallpox.

Smallpox was rightly feared

For many centuries, smallpox was a truly terrifying disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control, it's not clear exactly when it first started infecting humans, but 3,000-year-old Egyptian mummies have been found with a rash very similar to the one caused by smallpox.

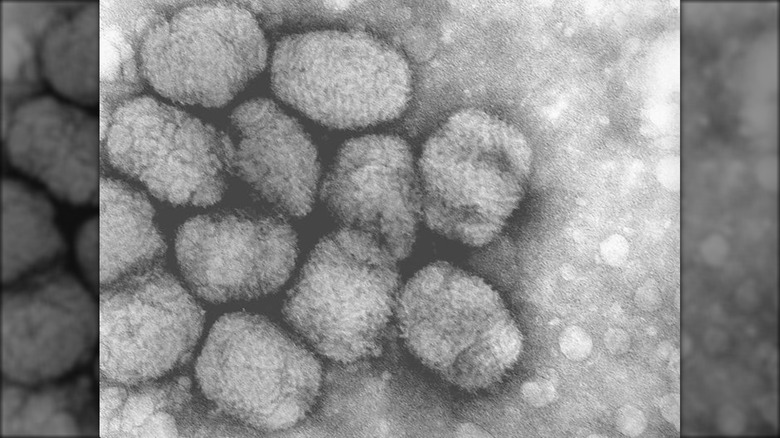

Smallpox is no easy disease to have. As the World Health Organization (WHO) reports, those infected first experience symptoms such as fever, headache, and fatigue. At this point, they have already been incubating the virus within their bodies for about two weeks. A couple of days after the flu-like symptoms appear, the rash that gives smallpox its name appears. It eventually spreads across the victim's skin and even inside the throat and mouth.

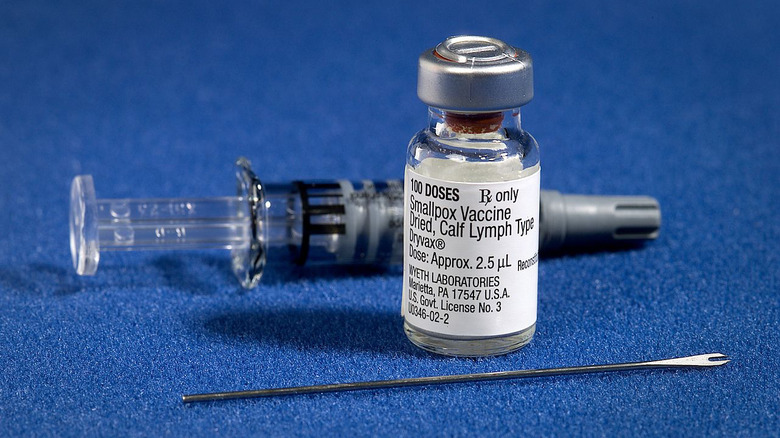

One variant referred to as variola minor results in a 1% death rate. The other type of smallpox, variola major, is far more common and far more deadly. Those infected with variola major faced an average death rate of 30%. Those who do survive are likely to be marked by prominent scars once the pustules that made up the rash heal. With all this in mind, it's perhaps not that surprising that the worldwide medical community was determined to eradicate smallpox. In 1967, the World Health Organization undertook a massive worldwide vaccination program in an effort to completely eradicate the disease. As the WHO reports, the global immunization effort was eventually a success, but not before it claimed the life of its last known victim in 1978.

Dr. Henry Bedson studied smallpox at the University of Birmingham

Even though smallpox seemed just about gone by the late 1970s, it still existed in research laboratories across the globe. Dr. Henry Bedson's lab contained samples of the virus after he petitioned the WHO for permission,

By the late 1970s, the WHO's efforts to vaccinate people against smallpox worldwide seemed to be working. According to The Guardian, only a trickle of cases were identified in the waning years of the decade. However, smallpox remained in a select group of laboratories, reserved for research purposes. In the middle of England, at the University of Birmingham, just such a lab existed. It was overseen by Dr. Henry Bedson, a virologist who was studying the different varieties of smallpox and how new strains might infect humans.

The vials of smallpox were refrigerated and contained within a small, sealed area of Bedson's lab. He had acquired the samples only recently, having traveled to London in May 1978 to accept them from a colleague. Work on a particularly virulent strain, named "Abid" after the young boy who contracted it, began in July (via The Guardian).

Janet Parker was a medical photographer

Bedson's microbiology lab with its small but highly restricted collection of smallpox samples was located in a basement level of the University of Birmingham, according to The Guardian. Just one floor above was a studio used by the university's medical photographers, including Janet Parker. There, Parker developed many of her photographs, though she was obliged to visit some labs in order to take pictures of tissue samples and the occasional animal subject housed on campus.

Parker had been a photographer for many years, first working for the local police as a crime scene photographer (via The Guardian). In 1976, she began work at the university's medical school, photographing slides and making other images for the researchers there. Her colleagues recall that she sometimes studied for a college degree she hoped to earn while on work breaks. As Birmingham Live notes, she was also known to take to her sports car, a Triumph Spitfire, and drive around town. Otherwise, her life with her husband, postal employee Joseph, and aging parents Fred and Hilda, seemed happy though unremarkable.

Parker grew alarmingly ill but no one knew why

According to the BBC, Janet Parker first realized that she was sick on August 11. She initially complained of a headache, body aches, and fatigue, per The Guardian, leading her to first think that she had caught the flu. Then the rash appeared. The red spots began to spread all over her skin, causing those around her to grow alarmed. A doctor initially said that Parker was experiencing a recurrence of chickenpox. However, she had already caught the virus as a child, which made it unlikely that she would get it again as an adult. Moreover, those spots began to pustulate, making them look different from the classic chickenpox rash.

Eventually, Parker became increasingly weak and was admitted to the Catherine-de-Barnes isolation hospital in late August. At this point, it seemed likely that there was something more than influenza or chickenpox hitting her immune system, but smallpox apparently wasn't the next guess for her doctors. According to The Guardian, Parker had already been vaccinated against the disease in 1966. And just a year earlier, news reports claimed that the last known person had been infected. Yet, Janet Parker was getting sicker and sicker, unable to stand on her own and with kidneys that had begun to fall. When infectious diseases specialist Alasdair Geddes studied samples taken from Parker, he could only come to one conclusion: it was smallpox.

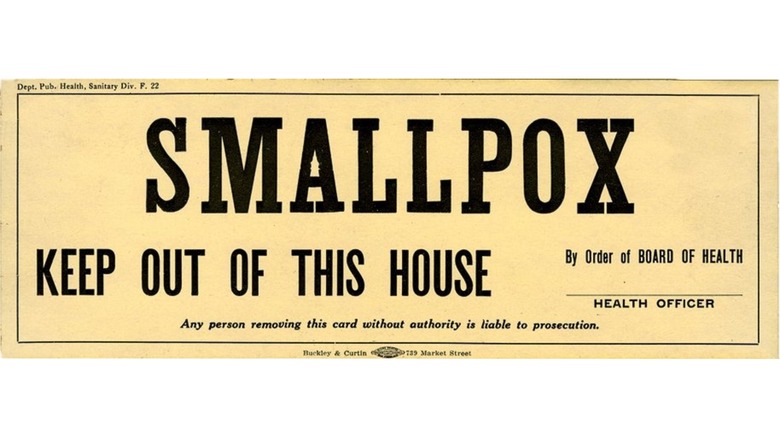

Strict quarantine measures were imposed in Birmingham

Once it was confirmed that Janet Parker had contracted smallpox, public health officers sprang into action. As The Guardian notes, smallpox has a fairly long incubation period of about 12 days, meaning there were nearly two weeks between when Parker first became infected and when she realized that she was ill. However, she would not have been contagious at that point, giving health workers a chance to stop the contagion. If they didn't move quickly or could not find anyone who might have been infected in a major metropolitan area, however, disaster loomed. Left uncontained, smallpox could potentially devastate Britain.

Ultimately, 260 people were isolated, having come into contact with Parker herself or someone else who had themselves been near a possibly contagious Parker. These included members of her family, work colleagues, and the ambulance crew who transported the ailing Parker to the hospital.

Members of the medical community, including the WHO, were worried that their hard work to eradicate smallpox would be undone by an outbreak in Birmingham. Dr. Surinder Bakhshi was in charge of much of the response in and around the city, which included vaccinations, antibody injections, contact tracing, and regularly undertaking in-home medical exams on those who came into contact with Parker or other possibly infected people.

One man caused a panicked nationwide search

In the wake of Janet Parker's diagnosis, doctors began enacting a protocol commonly known as "ring vaccination." Per the CDC, ring vaccination means that anyone who came into direct contact with a confirmed smallpox case will be vaccinated. Then, anyone who came into contact with someone in that first ring of people will also receive a smallpox vaccine. The strategy requires fairly robust contact tracing that outlines just who crossed paths with an infected person.

Reg Wickett, an engineer who worked at the hospital where Parker was admitted, was identified as one of those people, according to Birmingham Live. He was given a couple of shots to be certain, though Parker hadn't been confirmed to have smallpox and he wasn't showing any signs of disease anyway. Then, assuming that all was well, he went on vacation with his family.

When authorities confirmed that Parker really did have smallpox, they realized that Wickett might just be spreading smallpox in another part of the country. They instituted a nationwide search, complete with frightening all-caps headlines urging him to return home. He eventually did just that, where he received two more shots. Then Wickett grew alarmingly ill, having had a severe reaction to the vaccine. He was admitted to the same isolation unit as Parker. Though he experienced severe fatigue and hallucinations, he never actually contracted smallpox and recovered after a few days.

Janet Parker died alone

Once she was confirmed to have smallpox, Janet Parker was placed in strict quarantine in Catherine-de-Barnes, cared for by nurses Linda Sunderland and Mary Neary and doctor Deborah Symmons (via The Guardian). The hospital facility was overseen by Leslie and Dorothy Harris, who had managed the building and grounds for more than a decade without seeing a patient.

After three weeks in the isolation ward, Parker was covered in painful pustules that affected her eyesight and made it impossible for her to do even basic tasks like brushing her teeth. She also developed pneumonia. Sunderland said that Parker was often conscious. "She was aware, and that must have been horrible," Sunderland recalled (via The Guardian).

Other medical staff eventually joined the team, caring for people who were suspected of contracting the virus or having a reaction to the vaccine. None, however, had it nearly as bad as Janet Parker, who continued to deteriorate. Then, as the BBC reports, Parker's father died on September 5 of what appeared to be a heart attack, though no one conducted an autopsy due to fear of contagion. It was reputedly brought on by the stress of his daughter's situation. Parker herself died on September 11. Her mother also contracted smallpox, but it was a relatively mild case and she survived, though she wasn't able to attend either her husband's or her daughter's funeral.

People were scared to handle Parker's remains

Once Janet Parker died, the difficulty of giving her a proper farewell without infecting further people became evident. According to the CDC, smallpox may not be as contagious as respiratory viruses like influenza, but it can still spread. In particular, the scabs and sores left behind on Parker's ravaged body could be full of viral particles. If someone wasn't careful around her remains or anything she'd touched in her last few days of life, they might also come down with the potentially deadly disease.

As the Birmingham Mail reported, Ron Fleet, the funeral worker who came to collect Parker's body found it placed in the middle of a garage floor, wrapped in plastic and saturated with disinfectant. Where other bodies would have been placed in a refrigerator, Parker's was not for fear of allowing the virus to multiply. For the same reasons, staff was reluctant to help Fleet place Parker's remains in his van. She was also cremated, as authorities wanted to be sure that the virus would be thoroughly eradicated. They even went so far as to provide a police escort for her body (in case a traffic accident provided the risk of further exposure), canceled all other funerals at the Robin Hood Cemetery where her remains were transported, and made sure that the crematorium was thoroughly cleaned afterward (via The Guardian).

Henry Bedson was blamed for Parker's death

In the wake of Janet Parker's painful death, a number of questions arose. How could a medical photographer have caught a highly contained virus? Who should be held responsible?

A government investigation, named the Shooter Inquiry for lead examiner R.A. Shooter, was one of the first official attempts to answer these questions. Investigators determined that much of the blame lay with Dr. Henry Bedson. They claimed that his lab was insufficiently equipped to handle the virus and that his staff had not received proper training to handle the deadly pathogen. What's more, Bedson allegedly misled inspectors, some of whom were WHO officials, by saying that the volume of work with the smallpox samples had decreased when in fact it has been increasing before Parker's infection. However, the report was met with resistance from the University of Birmingham, not least because official inspections had given Bedson the go-ahead despite the apparent lack in both the facility and staffing.

Bedson was horrified to learn that he might have been responsible in some way for Parker's death. The accusations, along with the pressure of the scrutiny from the press and the medical and academic community, proved to be too great for him. Before Parker herself succumbed to smallpox, Bedson died by suicide at his home. According to the BBC, he wrote that he was "sorry to have misplaced the trust which so many of my friends and colleagues have placed in me and my work."

Bedson may not have been as guilty as first thought

It's still unclear how Janet Parker was infected. No records indicate that she ever entered the room within Bedson's lab that contained smallpox. According to The Guardian, the Shooter Report concluded that the virus must have traveled through the building's air ducts from the lab, then outside, and through a window to Parker's studio on the floor above. Yet, smallpox is not an airborne disease. Ill people may spread the virus by sneezing or coughing, especially once the rash has moved into their mouth.

However, for someone to be infected that way, they would have to be standing fairly close to a sick person and not necessarily near an air vent or an open window an entire floor away. Furthermore, lab workers were handling diluted samples of the virus strain that infected Parker, making it all the more difficult to believe that smallpox reached her through the air.

But then how else did she get sick? It's possible that Parker had contracted the virus by visiting the lab directly, perhaps while taking orders for photographs. Eleven years earlier, another medical photographer in the same program contracted smallpox, though he survived. Per The Guardian, the method of transmission may have been as simple as Parker touching an order list that had been contaminated. Meanwhile, it's worth noting that numerous inspectors noted only minor issues with Bedson's lab, ultimately giving him and his team the go-ahead each time.

Smallpox was eventually eradicated from the human population

Though researchers clearly thought that smallpox was on its way out, the case of Janet Parker made it all too clear that there was still work to be done. Yet, there were some silver linings. In the immediate aftermath of Parker's diagnosis, medical officials mobilized quickly and relatively effectively. As The Guardian reports, hundreds of medical personnel came together to keep a prospective smallpox outbreak from happening, including an estimated 60 doctors and 40 nurses. By October 16, 1978, their efforts paid off: Birmingham was officially deemed to be free of the contagion.

Just two years later, on May 8, 1980, the WHO declared that smallpox was finally eradicated from the worldwide population (via Vox). Many of the tactics used in Birmingham were part of the larger attempt to stamp out smallpox, including ring vaccination. This technique proved to be especially useful in places with limited resources, allowing health officials to concentrate their efforts around known cases instead of trying to absolutely vaccinate everyone in a given region.

Ultimately, it worked. Since Parker's death, there have been no known fatalities from smallpox. Yet, that's no cause to relax. Smallpox is still contained in small labs and must be managed carefully. According to Vox, deadly diseases have escaped from labs before. And, though we can't be sure exactly how Parker became infected, it seems clear that the virus escaped the lab and reached her immune system somehow. Careful handling of smallpox is vital.

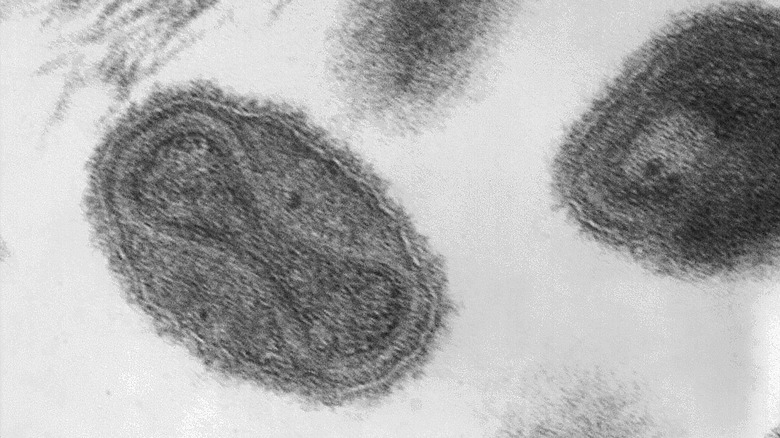

The viral strain that killed Janet Parker is still around

Though it's still not clear just how Janet Parker became sick with smallpox, we do know the exact pathogen that infected her. It was known as the "Abid" strain, named after a young boy from Pakistan who had been infected in the 1970s. Bedson's lab had been working with it at the time of Parker's infection (via The Guardian).

According to Birmingham Live, the Abid strain now resides in a tightly controlled CDC lab in Atlanta. Still, some worry that these closely guarded samples could still get out or that other pox viruses could be created as bioweapons. Close calls have certainly happened before. According to Science, in 2014 a series of vials containing the virus were discovered in a lab at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland. The freeze-dried samples had been acquired in the 1950s. Previously, other small labs had uncovered and destroyed similar unsecured samples.

For some, the answer to this dilemma is obvious: destroy the last remaining smallpox samples. It should be easy, since, according to Science, the only two places to still have smallpox viruses are labs in Atlanta and Novosibirsk, Russia. Yet, The Guardian reports that some scientists want to hold on to smallpox for further study. The CDC also acknowledges that smallpox could be used as a bioweapon. For some, that's enough cause to eradicate the last known samples, while others may want to hold on to them for vaccine development.