The Untold Truth Of Barnabas

The apostle whose given name was Joses, or Joseph, has gone down in history as "Barnabas," which means "son of encouragement," a nickname given to him by the early Christian community. True to his name, after his conversion he served Jesus Christ in the humblest of ways, supporting Saul — later to take the name Paul — in his faith journey, introducing him to the rest of the Apostles and vouching for his conversion of heart despite the fact that Paul had been a feared persecutor of Christians.

Some scholars believe Barnabas may have written epistles that are now part of the New Testament, and there is even an intriguing and controversial work called the Gospel of Barnabas — which he most likely did not write.

True to his name, Barnabas is remembered for his unflagging encouragement of his fellow disciples, rather than his own accomplishments. If not for Barnabas, Christianity might not have much of what we know as the New Testament, which the New Advent Encyclopedia explains was traditionally said to be written by his companions in the new faith.

Barnabas headed a community where the faithful were first called Christians

A Jewish man born in the ancient city of Salamis on the island of Cyprus, Barnabas was one of the earliest Christians, joining them soon after the Resurrection, selling his property and giving the proceeds to the band of Jesus' followers in Jerusalem soon after he converted, as noted by the Biblical scholar Carl Gustav von Harnack. He then was made leader of the new community of faith in Antioch, the first place where believers were called Christians, according to Acts 11:26. His selfless actions were notable even amongst the other disciples. As Robin Gallaher Branch states in "Barnabas: Early Church Leader and Model of Encouragement," due to the context of a passage praising these qualities, it "may well be that the character traits of Barnabas defined the early use of the word Christian." Barnabas was recorded in the Bible as doing exactly what Jesus had encouraged them to do, as the Lord told the "rich young man" in Matthew 19:21: "Go, sell all your possessions and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me."

This was, and still is, a radical notion; however, this sharing of resources lasted for a time amongst Christ's followers. Luke writes in Acts 4:34, "There was not a needy person among them" after the distribution of the monies from property sales.

Barnabas introduced Paul to the Apostles

A new convert himself, Barnabas introduced Saul (Paul) to the other apostles and vouched for him to become a member of the fledgling faith; Saul was still greatly distrusted by them since he had been one of their most prominent persecutors. As Luke writes in Acts 9:26-28, "they were all afraid of him, not believing that he really was a disciple." Barnabas then related the powerful story of Saul's thunderbolt-like conversion to his fellow believers, convincing them of its authenticity.

As an article in the Journal of Biblical Perspectives in Leadership notes, as a Pharisee, Saul was accustomed to the practice of humbly learning from others; their mentoring relationship marked a crucial juncture for Christianity as Saul learned how best to explain Jesus' teachings to other Jews and to the wider world. This was undoubtedly one of the pivotal moments in the history of Christianity since Paul went on to write much of the New Testament and was one of its most tireless missionaries, traveling throughout the Mediterranean world and founding churches wherever he went.

Scholar Wayne Meeks states (via PBS) that next to Jesus himself, Paul is "clearly the most intriguing figure of first-century Christianity and better known than Jesus because we have all of those letters that he wrote as primary sources." Paul thought of himself "primarily as a prophet to the non-Jews, to bring to them the message of the crucified Messiah," Meeks adds. So it is the self-effacing Barnabas to whom much of the New Testament is owed.

Pagans thought Barnabas was the Greek god Zeus

After he had built up the church at Antioch and realized it was time to evangelize the Gentiles, Barnabas traveled to Tarsus, getting Saul out of retirement for this purpose, as Pope Emeritus Benedict relates. A Jew who had been born in a Gentile land, according to Acts 13:3, Barnabas had been chosen to lead the first Christian mission to non-Jewish areas, including Cyprus, Pamphilia, Pisidia, and Lycaonia; he and Saul departed after a laying on of hands to bless them in their new venture.

Presaging what was to happen as time went on, the duo was always referred to as "Barnabas and Saul" until Saul took the Hellenized name of Paul; thereafter they were nearly always called "Paul and Barnabas," signaling the primacy of Paul as an apostle of the burgeoning faith, as noted by religious historian Carl von Harnack.

Naturally, they experienced many adventures on these early travels; in one of the most evocative images of the entire Bible, Acts 14:12 states the pagan Lystrans, who lived in what is now Turkey, were so convinced that Barnabas was the Greek god Zeus that they insisted on making animal sacrifices to him; likewise, because of his great eloquence, they believed Paul was actually the Greek messenger god Hermes. Incredibly, that attempt at evangelization ends with Paul being stoned; however, the duo escapes and gains followers for Christ in the city of Derbe the very next day.

Barnabas was involved in an early Judaic law controversy

How closely to follow Jewish laws was an enormous dilemma for the early Christians; Peter's famous dream about all of the "unclean" animals of the world appearing before him was undoubtedly sparked by this pressing matter. In addition, the issue of whether or not Christian males must be circumcised, like Jews, was a crucial one, as more and more Gentiles converted to the new faith. In the beginning, most believed that Christian males did indeed need to be circumcised, as noted by Alister McGrath in his work "Christianity: An Introduction."

However, there was a great deal of controversy about this matter, and as Luke relates in the Book of Acts, "it was decided that Paul, Barnabas and some of the others should go up to Jerusalem" to try to arrive at a decision on the question. Although the issue was settled at the Apostolic Council at Jerusalem in the year 48 AD, at which Peter appeared to take precedence over the other apostles, Barnabas was still bedeviled by this lingering controversy for the rest of his missionary career. Gresham Machen states in his work "Christianity and Liberalism" that new Christians referred to as the "Judaizers" believed that circumcision was absolutely needed, and they kept up their arguments despite the Jerusalem decree.

However, it was that decision more than any other that grew the church beyond its first Jewish adherents to become "the Church of the Gentiles," based on faith alone.

Barnabas was involved in the first major disagreement amongst Apostles

Paul asked Barnabas to go with him on a second mission in the year 45 AD; Barnabas wanted his cousin Mark the Evangelist along as well, but Paul did not, since Mark had abandoned their earlier mission. This caused a serious rift amongst the Apostles -- the first one to be recorded in the long Christian history of misunderstandings and schisms.

This admission, by Luke, of a less-than-ideal relationship between the members of the new sect, shows that he valued honesty and attempted to portray the apostles as the flawed people they were in real life. As he says in Acts 15:36-41: "They had such a sharp disagreement that they parted company," with Barnabas and Mark traveling back to Cyprus while Paul was off to evangelize Syria and Cilicia, strengthening the churches already in existence there.

All in all, however, many scholars believe that admitting that the Apostles quarreled amongst themselves strengthened, rather than weakened, Christianity in the long run. As Pope Emeritus Benedict states, "I find this very comforting, because we see that the saints have not 'fallen from heaven.' They are people like us, with complicated problems." It also indicated that Barnabas himself may have made possible the Gospel of Mark, who may not have taken part in any future evangelization efforts if not for Barnabas standing up for him.

Barnabas was appointed Archbishop of Salamis in 45 AD

Barnabas was named Archbishop of his birthplace, the Cypriot city of Salamis while he was in Jerusalem; he was installed in 45 AD, when he, Paul, and Mark the Evangelist arrived again on the island. He was singled out as an especially hard-working apostle who served the church only after his daily work was done, refusing to live off the communal monies; as Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 9:6, "Are Barnabas and I the only ones who must work for a living?"

He may also have preached in Rome itself, perhaps even while Christ was alive, although there is no relation of this in sources other than the "Recognitions of Clement," the work of a man who may have been Pope Clement I, who reigned from 88 to 99 AD. Clement states that he personally listened to Barnabas preaching in the city and began following him then. Barnabas convinced people of the veracity of his arguments by producing many "witnesses to the sayings and marvels which he related" from the life of Christ, according to Clement, who added that Barnabas also preached in Alexandria, per the Jewish Encyclopedia.

A Greek text known as "The Seventy Apostles of Christ," included in the 9th-century lectionary that is part of the Codex Barocchianus No. 206, now located in the Bodleian Library, names him as one of the 70 Apostles referred to in the Gospel of Luke, which recounts Jesus' sending of the men to evangelize the world.

Stories of Barnabas' martyrdom circulated in 3rd century

Traditions related to Barnabas' missionary work and the story of his martyrdom by dragging and/or stoning in Salamis began to circulate in the third century AD, prompting early Christians to try to find his remains and claim them for the Cyprus church. Noted Orthodox scholar John Sanidopoulos states that in the year 57, "the Jewish community of Salamis objected to his preaching in the synagogue and had him dragged out, tortured and stoned to death." Indeed, almost all of Christ's Twelve Apostles and many disciples were martyred for their beliefs; of the Twelve, only John lived to old age and died a natural death, at Ephesus.

The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that it is likely that Barnabas was no longer alive as of 61-63 AD, when Paul was imprisoned at Rome, since Mark was attached to him as a disciple, not his cousin Barnabas.

"The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church" relates the legend surrounding the death of the apostle who was noted for encouraging others. It states that the earliest mention of his death is in a sermon by St. Peter Chrysologus, a bishop of Ravenna, Italy who died approximately 450 AD, and who indicated that Barnabas had in fact been martyred at Salamis, the city of his birth, in 61 AD.

Archbishop Anthemios claimed Barnabas appeared to him in a dream

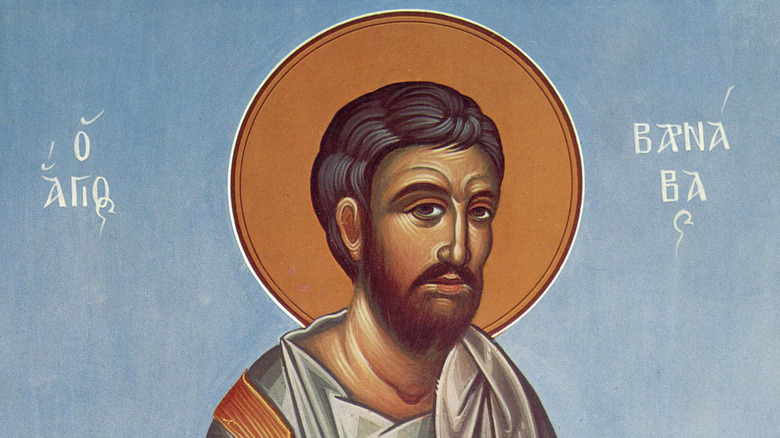

In the year 478, Anthemios, the Archbishop of Cyprus, claimed that Barnabas had appeared to him in a dream, revealing the location of his burial place under a carob tree. Orthodox scholar John Sanidopoulos relates the legend of his grave being unearthed the next day; a copy of the Gospel of Matthew, laid there by his cousin, Mark the Evangelist, was found on his chest. This is why Barnabas is often portrayed with the Gospel of Matthew in iconography.

The remains of the heroic apostle who hailed from Salamis were used to distance the Cyprus church from Antioch, the first organized Christian church, and to legitimize its autonomy, according to Carl von Harnack.

The story of the discovery of the remains – perhaps apocryphal – was related in the work "Laudatio Barnabae," written in 550. The archbishop gave a copy of the Gospel to Emperor Zeno in Constantinople in 488, who granted the Cyprus Church autocephaly. A beautiful stone church was constructed on the very spot where the body was found; a stopover for many Christian pilgrims on the way to Jerusalem, it still exists today as part of the monastery of St. Barnabas in Famagusta, operated as a museum in occupied northern Cyprus, according to Agnieszka Makowiecka and Robert Pasieczny, editors of Eyewitness Travel Cyprus.

The Gospel of Barnabas was declared noncanonical

The so-called "Gospel of Barnabas," which only exists in Italian and Spanish, appears to date back only to Medieval times, according to almost all scholars across the globe. It was never cited by any writer throughout the 2,000-year history of Christianity before one 18th-century mention by John Toland, Biblical scholar Jan Joosten states; indeed, it contains a number of inaccuracies and anachronisms, as noted by J.N.J. Kritzinger in "A Critical Study of the Gospel of Barnabas."

These glaring problems include confusing the location of Nazareth, where Jesus was born, with Capernaum, where He and the disciples preached. Then there's the use of wooden barrels to store wine — which is a European custom — rather than wineskins, as was customary in the Middle East; this was even related in the canonical Gospels in the parable of the wineskins in Matthew 9:17. And the text uses the word "baron" to describe the landowner Lazarus, who it claims owned the cities of Magdala and Bethany. In reality, that Medieval European term was never used in Judea at all, Kritzinger notes.

The discredited document echoes the arguments of Islamic scholars, including the assertion that Christ was not crucified, which Muslims believe. Biblical scholar Jan Joosten notes in a paper in the Journal of Theological Studies that it was most likely written in the 14th century. Moreover, another glaring anachronism is that Old Testament quotations reflect the Latin Vulgate bible, which St. Jerome only began writing in the year 328.

A patriarch claimed Barnabas wrote the Book of Acts

Photius, the Patriarch of Constantinople in the 9th century, who was a noted religious scholar, claimed that some believed Barnabas himself may have written the Book of Acts in which so many of his missionary journeys to the Gentiles were recounted, not Luke the Evangelist, as related by Carl von Harnack in the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge.

However, almost all Biblical scholars believe, as Alfred Plummer noted in 1898, that Luke the Evangelist is actually the author of the Biblical book that recounts the events after the crucifixion. This almost offhand assertion of Photius' has been roundly disparaged by a host of scholars, including James Stevenson Riggs, who notes that it almost certainly is Luke, "the beloved physician," from Philippi, in Macedonia, who authored Acts, as he stated in "Who Wrote the Book of the Acts?" This is because Luke, the companion of Paul on many of his missions, gave such exhaustive detail about Paul's personality, which would not have been possible from any other early Christian.

The Epistle of Barnabas was declared noncanonical

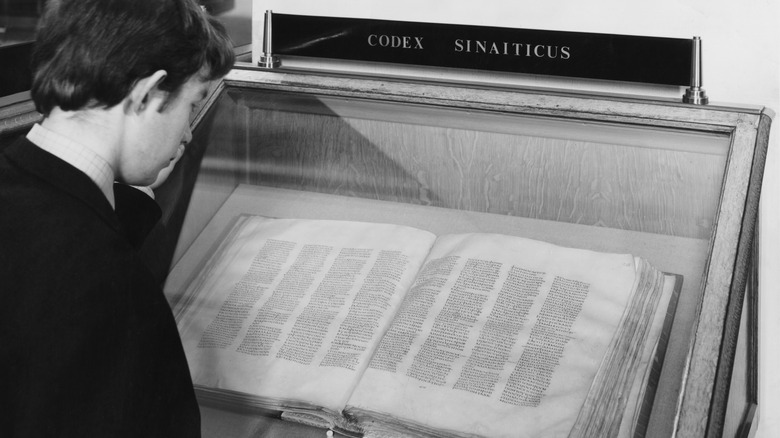

Barnabas may have been the author of the so-called Epistle of Barnabas, written in Greek; it had been at one time included in the Codex Sinaiticus, appended to the New Testament, as noted by scholar Kirsopp Lake in his translation of "The Apostolic Fathers." A 4th-century manuscript of the Codex was discovered in 1859 by Constantin von Tischendorf and published by him several years later.

Both Clement and Origen of Alexandria, both early Church Fathers, approved of the Epistle, with Origen including it as canonical in his work "Contra Celsum," written in the year 248 as a refutation of allegations made by Celsus, a pagan who had attacked Christian beliefs. Clement of Alexandria also included it in his work "The Stromata" and "The Recognitions of Clement."

However, the eminent bishop Eusebius, who lived in the 4th century, disagreed with these writers, and it soon vanished from the appendix to the New Testament, as related by Carl von Harnack. James Rochford notes on Evidence Unseen that most modern scholars agree; there are several indications that it was written by someone in Alexandria in the years 130-131, and several passages appear to be quite antisemitic, meaning that it was written by and for Gentile Christians. The author, who says he was a regular congregant in the assembly to whom the letter is written, states that only Christians have a covenant with God; the Jews never did. Scholars say this is the strongest statement made against the Judaizers.

The Catholic religious order The Barnabites honors his memory

According to The New Advent Encyclopedia, Barnabas, who was undoubtedly instrumental in helping open up Christianity in his many missions to the Gentiles, in his participation in the Jerusalem Council, and in encouraging other disciples to join and remain with the followers of Jesus, "was the most esteemed man of the first Christian generation."

A religious order called The Clerics Regular of St. Paul, known as The Barnabites, was formed in 1530 at the church of St. Barnabas in Milan, Italy, where some believe Barnabas served as bishop. Still in existence, the Barnabite order has a particular devotion to the Epistles of St. Paul, because of the close ties between Paul and Barnabas. It is they who keep the memory of St. Barnabas alive despite the fact that Paul rose to such prominence as a missionary of early Christianity that he in many ways eclipsed the man who was instrumental in his joining of the Christian movement.

The final, glowing epitaph for Barnabas, who is best known for putting others first — as Jesus told everyone to do — was from the Apostle Luke, who wrote in Acts 11:24 that Barnabas was "a good man, full of the holy spirit and of faith."