How Two Vodou Priests Helped Spark The Haitian Revolution

Out of all the binding forces of human society, music and dance stand out as the most potent, primal, and empowering. There really is something about music that transcends language, even to a near-mystical extent. Even legendary writers — word people — like Leo Tolstoy thought so (per Goodreads). Indeed, modern psychology posits that language — rhythm, pitch, cadence, etc. — not only developed after musical understanding but as a result of it, as Psychology Today overviews.

The power of sound to bind people together, especially in a ritual context, should be obvious to any of us. What else is happening at a concert? Or for that matter, a church service? As a study published in Frontiers in Psychology explains, available at the National Library of Medicine, music creates a "self-other" merging, especially during "synchronized exertive movements." Dance, in other words.

So what would happen if you pack together hundreds of thousands of individuals on a small island where none of them speaks the same language? But, they share a couple of common threads: the suffering of the present and the myths of the past. This is exactly what happened during the era of rampant colonization in the Americas from the 1500s through the 1800s. Men and women from various West African tribes were enslaved, transported to a new land, and needed all the resources, rituals, and, dare we say "magic," to break free. Enter Vodou and the Haitian Revolution, ignited by a single rite on a single night in 1791.

The colonial roots of a revolution

To understand the Haitian Revolution, we've got to back to the whole, messy, absurdly convoluted web of colonial meddling in the Caribbean that characterized practically the entirety of the Americas in the late 15th through late 18th centuries. After Christopher Columbus landed in the Bahamas in 1492, it took only six years for Spain to establish a colony in the modern-day Dominican Republic in 1498. Its capital was dubbed Santo Domingo, which nowadays thanks to its history and architecture is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

For those needing a geographical refresher, the Dominican Republic and Haiti share the same island, which still bears its 15th-century name, Hispaniola. Haiti takes up the western one-third, and the Dominican Republic is located on the two-thirds to the east of the island. But until 1697, the whole thing belonged to the Spanish. The Treaty of Rijswijk, drafted between England and France, split Hispaniola into its current countries at the end of King William's War (1689 to 1697). For a bit, this quieted the incessant series of conflicts and land grabs in the region, as Britannica outlines.

The French, who now owned one-third of Hispaniola, simply did a language swap of the Spanish "Santo Domingo" into "Saint-Domingue." Over the next 100 years or so Saint-Domingue grew into the wealthiest settlement in the Americas, fueled by products like sugar, coffee, and indigo and cotton crops, as History explains. And like the rest of the nearby colonies, such goods were farmed and produced using slave labor.

A stratified, slave-based economy

By the 1780s, as Britannica says, the small landmass of Saint-Domingue retained a full two-thirds of French foreign investments. Every year over 700 ships used it as a stopover along various trade routes. All of this wealth required lots of labor, and even as enslaved people sheared forests of trees to make room for crops, and the island's topsoil began to erode, investors and landowners demanded that more and more enslaved people kept getting pumped into the colony to yield greater returns. These men and women were invariably taken from various West African tribes.

As expected, the colony's population was divided along harsh racial and economic lines. Over the 18th century, such divisions took on an extreme, regimented, and bizarrely categorical form. At the top of the heap was the "grands blancs," which yes, means "great whites." These were high-ranking merchants and landowners, even members of noble families from France. Under them were the "petits blancs" ("little whites"), which included plantation overseers and craftsmen, and then "blancs menant," laborers, peasants, etc. At the bottom, but still above the enslaved, were "affranchis," free, mixed-race individuals with both European and African ancestors. Even affranchis were permitted to hold people in bondage — and did if they could afford it.

By 1789, the entire colony of Saint-Domingue had grown from less than 60,000 colonists and affranchis to a population of 556,000 people — 500,000 of them were enslaved. That majority carried with it a key component from the old world: traditions that would form the foundation of Vodou.

The social glue of Vodou rituals

In a very real sense, Vodou was critical for the enslaved people of the future Haitian nation to band together in unity, keep their connection to their original, lost home, and also to the inner fire needed to drive a revolt against unjust authorities. Even at present, as The Guardian quotes, Haiti is "70% Catholic, 30% Protestant, and 100% Vodou." As photographer Hector Retamal discusses on Vice (via YouTube), people in Haiti conduct Vodou rituals as part and parcel of daily life, particularly its characteristic dances and trance states. Vodou is not, it should be noted, a direct copy-pasted religion lifted from West African tribes and transmigrated to the Caribbean. Tribal members brought to Saint-Domingue didn't share the same lineage or even the same language aside from their then-common tongue, Haitian Creole (derived from French). Vodou is an emergent set of practices originating in the stew of colonial slavery and a multiethnic African diaspora.

By the late 1700s, the enslaved peoples of Saint-Domingue had just about had enough. Even landowners and societal elites wanted independence from France, but for utterly different reasons of greater economic control, as English Heritage explains. The timing isn't coincidental, either. As History says, the flames of independence were inspired by, ironically so, France's own revolution that ended in 1790. By August 1791, plans were in motion. But it was a Vodou ritual that kicked the revolution off and inspired all those involved, led by priestess ("mambo") Cecile Fatiman and priest ("oungan") Dutty Boukman.

Invoking the spirit of Erzulie Dantor

The ritual in question took place at a secret gathering of the enslaved called Bois Caïman, which Hougan Sydney places on the night of August 14th in the woods near Boukman's house. Boukman, as oungan, would have started the ritual with a rousing speech. Fatiman, as mambo, would have sought possession by the spirit of a Vodou deity, or "Lwa," who act as intermediaries between humans and the supreme creator deity. In particular, she would have sought possession by Erzulie Dantor, a dangerous, blood-drinking entity. As an article published on Duke University's The Black Atlantic series cites, a pig was likely also sacrificed at some point.

Vodou, as The Guardian explains, revolves around states of frenzy and trance, and places a huge emphasis on music and dance. Lwa, in fact, in addition to having their own distinct personalities and multiple aspects, have their own music, dances, and world items that attract them, as Dr. Kate Kingsbury writes on Research Gate. Vodou practitioners also use drawings — "vèvè" — used to summon Lwa, while mambo, as the contact point between the earthly and the divine, wield rattles called "ason" (via Harvard University).

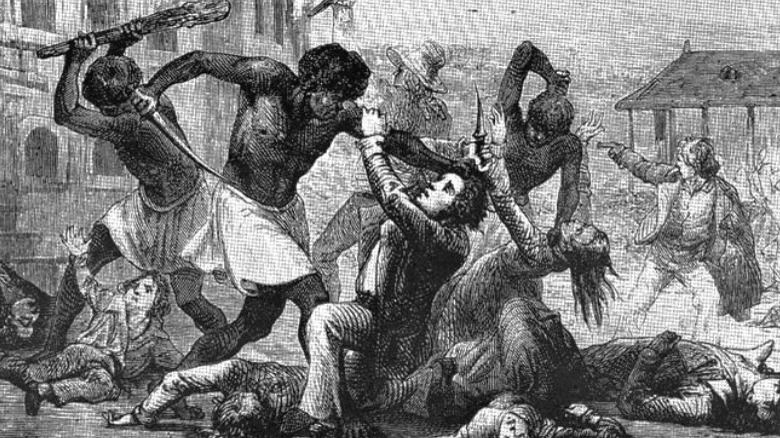

We can assume all of this happened in some form or another back in 1791. Barring any belief in the supernatural, such a meeting would have at least emboldened the enslaved people of Saint-Domingue to carry out their revolution. Within a few weeks, the revolution's over 100,000 participants destroyed hundreds of plantations, as the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation states.

The first black nation outside of Africa

When plantations started burning, the French government across the ocean took notice. A mere six or so months after the gathering at Bois Caïman helped ignite the Haitian revolution, France "abolished racial discrimination among free citizens" on April 4, 1792 (via English Heritage). This wasn't enough, though — not by far — and Haitians would continue fighting for their independence all the way to 1804.

The most prominent figure during the revolution itself was François-Dominique Toussaint L'ouverture (1743 to 1803), the "Father of Haiti." Born into slavery in Saint-Domingue, we don't know much about his early life. But as Europeana says, we do know that he was educated by his godfather Pierre Baptiste, who taught him French as well as the type of Enlightenment philosophy that had spurred the French Revolution. Toussaint adopted the last name "L'ouverture" — "the opening" — in 1793.

When the revolution broke out, as History says, L'ouverture kept a low profile. A tactical thinker, he played colonial powers against each other while his troops slowly chipped away at their forces. He was captured by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802 and died in prison in 1803, the year before Haiti officially won its independence in 1804.

Haiti became not only the first Black nation outside of Africa, but the second colonial nation in the Americas to win its independence. To this day the gathering at Bois Caïman, and Vodou in general, remain emblematic of Haitian identity and freedom.