The History Of Oklahoma's All-Black Towns

Discrimination has been an inescapable fixture of life for many African Americans. Yet, since the time of slavery, Black communities facing prejudice have found creative and enterprising ways to maintain their dignity in the face of white violence. Even as the oppression and trauma of the Jim Crow laws were taking hold after the American Civil War, areas like Oklahoma, which, as the London Review of Books points out, had not been part of the Confederacy and was fighting to be given statehood, were doing things differently.

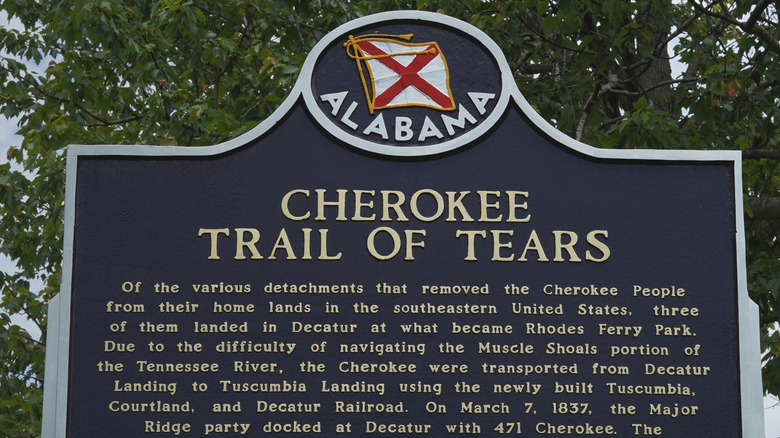

This included its status as "Indian Country," a result of Native Americans having been forced to migrate there to make space for white settlers wanting to grow cotton (known as the Trail of Tears). Many brought slaves with them, and when the slaves were emancipated and Native American communities moved out of the state, these newly freed peoples carved out a niche for themselves through the creation of all-Black frontier towns.

Life could be tough, and white violence could never be kept completely at bay; but many such towns experienced decades of prosperity and community cohesion that were enjoyed and valued by the descendants of freed slaves. While economic and political disenfranchisement, combined with the devastating global effects of the Great Depression, meant most of these towns eventually declined, memories of the more prominent ones are still fresh in Oklahoma. Below are details of their origins and identities, and the efforts by activists to keep the ones that remain alive.

How did they begin?

More than 50 Black communities sprang up in Oklahoma between the American Civil War and the Great Depression. They had their origins in slaves brought there by Native Americans, who had in turn been ejected from their land in Florida and Alabama, during the displacements between 1830 and 1850, which became known infamously as the Trail of Tears (via McAlester News-Capital).

Many Native Americans had sided with the Confederacy, and saw Black people as property or assets in the same way that many white slave owners did. Yet when slaves in the Cherokee Nation and Creek Nation were declared to be free in 1866, per signing of the U.S. Treaty with the Cherokee Nation and Creek Nation (via BlackPast [1], [2]), the Native American nations who owned them were required by the U.S. government to give them up. Many Native Americans moved out of Oklahoma, and the state became a magnet for Black people no longer crippled by bondage and seeking better economic opportunities.

Innately rural, agriculture was at the heart of a lot of these communities, providing a livelihood that in turn spawned the founding of churches, schools, universities, sports teams, and forms of local government.

Tullahassee

The town of Tullahassee is considered to be the oldest of Oklahoma's all-Black communities that blossomed in the late 19th century, as explained by The Washington Post.

A school was founded there by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in 1850, but the combination of Black people being granted freedom and citizenship in 1866, and the Nation moving its peoples out in 1881 after a devastating fire, meant that the Black community thrived and prospered — even after segregation arrived in 1907.

At its height, Tullahassee could boast shops, offices, a gas station, and a post office, as well as a hotel, a movie theater, and a railway depot, per the Oklahoma Historical Society. In 1916, the first private university for Black citizens, Flipper Davis College, was opened in the rebuilt former Creek school. There was also a school for African Americans, Carter G. Woodson (via the Post), and a community gymnasium. At one point, Tullahassee had 209 citizens. It now has less than half that number.

Greenwood

Tulsa was transformed from a quiet village into a bustling center of prosperity when oil was discovered nearby in the years prior to 1921. As highlighted by British literary magazine the London Review of Books, Tulsa's predominantly Black area of Greenwood housed around 10,000 residents, who, due to their exclusion by white society, founded their own businesses and networks of community support.

Per LBR, the Greenwood District was given the moniker, the "Black Wall Street," by activist Booker T. Washington. Even though many of the town's residents worked as maids and cooks in white houses, Greenwood was also home to Black lawyers, bankers, and more Black doctors than in the whole of current-day Tulsa.

Furthermore, Greenwood contained flourishing local businesses, including grocery stores, cinemas, newspapers, clothes shops, churches, and restaurants. These businesses prospered until a massacre by white terrorists in 1921, prompted by the arrest of a Black teenager, Dick Rowland, who had been accused of assaulting a white woman.

Although Rowland escaped being lynched, the attackers who descended on Greenwood on May 31, killed between 100 and 300 other people and destroyed at least 1,500 buildings in the span of two days, according to the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum, in what will become known as the Tulsa Race Massacre. Only the arrival of police from the Oklahoma state capitol brought a stop to the violence.

Boley

Boley was founded in 1903 and became a magnet for Black settlers in Oklahoma after the town's mayor established a railway depot and declared it capable of self-governance. Many of the town's occupants lived with memories of slavery, but as it was declared to be a town "by Blacks, for Blacks," according to Jessilyn Head (via NonDoc Media), who runs the nonprofit Coltrane Group on Oklahoma, Boley residents lived lives that were far more free from prejudice and oppression than many Black people in racially mixed areas did.

The Oklahoma Historical Society says Booker T. Washington called Boley "the most enterprising and in many ways the most interesting Negro town in the United States." The residents who lived there established groundbreaking institutions, like the first Black-owned bank in America to be granted a national charter, meaning it could operate in the same way as white banks. (An attempted burglary was even made on the building in 1932 by a local gang). Other industries were set up, such as a steam power plant and electronics and telecommunications companies.

Interestingly, according to the State Historic Preservation Office, the town's name came from J.B. Boley, a white man who believed in the right of former slaves to practice self-governance. By 1911, Boley had 4,000 residents, many of whom had been attracted by adverts in Black newspapers, and had two colleges as well as hotels, restaurants, and grocery stores. As of 2021, the population in Boley is just over 1,000.

Taft

Founded in Muskogee County, Taft was described as the "fastest growing" Black community in Oklahoma, according to the State Historic Preservation Office. By 1902, Taft had acquired vital amenities, such as a functioning post office, as well as a university and two newspapers, the Tribune and the Enterprise, and a cotton gin for separating cotton fibers from seeds — a major asset when so many towns were reliant on agriculture.

In terms of education, Taft had some unique facets, including a pioneering orphanage for visually impaired and hard-of-hearing Black children (the Industrial Institute for Deaf, Blind and Orphans of the Colored Race) and a reform school solely for African American girls, known as the State Training School for Negro Girls.

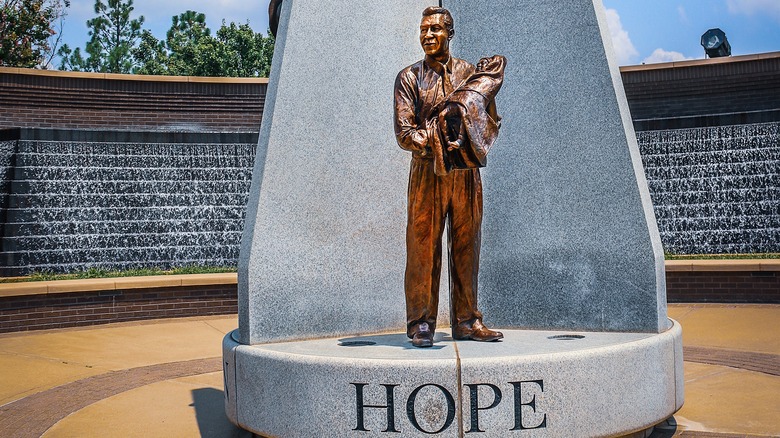

In 1973, the town elected Lelia Foley-Davis, the first Black and female mayor in the United States. As reported by News 9, Foley-Davis was a trailblazer and would go on to meet with three U.S. presidents, the first being President Gerald Ford, who invited her to the White House — a meeting that would lead to the expansion of the rented housing sector in Taft. She also met with Presidents Jimmy Carter and Barack Obama.

As of 2010, Taft's population stands at only 250.

Langston

Set up in 1890, the town of Langston drew in 251 Black settlers within its first year. As described by NonDoc, one of the town's founders, E.P. McCabe, once told the Langston City Herald that Langston was a town where Black people could "rest from mob law" and "be secure from every ill of the Southern policies."

McCabe's efforts at encouraging migration into the area were largely successful, so much so that by 1891, the town had drawn in 600 new residents. By 1893, BlackPast noted that Langston was home to 25 small businesses, including barbershops, ice cream parlors, and saloon bars.

Langston went on to build an all-Black college in 1897 that later became Langston University, the only all-Black public university in Oklahoma. According to the State Historic Preservation Office, a Roman Catholic missionary presence was also established alongside churches from other denominations, a fire service, and a local militia. Despite their best efforts, the townsfolk couldn't attract a railway line, however.

Regardless of shrinking populations in most former all-Black settlements, in 2010, at least 1,724 residents still called Langston home. As of 2019, the town's university had an undergraduate population of 3,400, roughly the same as the population of the town, which has helped it survive and remain the largest of Oklahoma's all-Black towns.

Clearview

Clearview was founded in 1903, starting out with little more than a school and two churches, according to NonDoc. By the following year, though, it had grown to accommodate a hotel, a print shop, a rodeo that continues into the present day, and a baseball team, whose games were so well-renowned that white spectators would come to see them. Although white visitors would often refuse to venture into the town, many were so keen to watch the high standard of skill on display on the sports pitch that they would spectate from the railroad tracks.

Despite the popularity of its sporting events, Clearview's population never rose much above 618, eventually dropping to 420 in the 1930s. As recounted by the State Historic Preservation Office, by 2010, the town had only 48 residents.

However, along with the rodeo, Clearview still preserves the Oklahoma African American Educators Hall of Fame, an institution celebrating educators who are often "unknown or recognized for their contributions in the educational field especially during the times of segregation."

What happened?

When Oklahoma became a state in 1907, racial segregation was introduced via the Jim Crow laws, a system of oppressive rules designed to enforce segregation and trap African Americans into lives of poverty and deprivation (via the University of Tulsa). The legislation also prompted racial violence from whites, particularly against Black people who lived close to areas dominated by whites, such as Tulsa. The Jim Crow laws left many African Americans feeling disillusioned and terrified of widespread acts of white terrorism; this encouraged many of them to move out of areas altogether, per Smithsonian Magazine.

Furthermore, as the University of Tulsa explains, the Great Depression forced residents in farming towns to seek work elsewhere, leaving them without a tax base and resulting in depleted resources, which further encouraged Black flight to Canada, in places like Amber Valley, Maidstone, and Alberta, as well as to Mexico. Others joined the burgeoning "Back to Africa" movement that grew in popularity in the 1920s and 1930s.

Meanwhile, for the Black businesses that stayed, white banks would refuse to lend them money, according to the Oklahoma Historical Society. Also, railroads often failed due to lack of maintenance, leaving many agricultural Black towns isolated. White leaseholders, such as those in Okfuskee County, tried at various points to block outward immigration, while also refusing to sell or rent land to Black farmers unless it was at least a mile from any white residents, or hire Black laborers. All of this led to the depletion of these once-thriving Black settlements.

Which ones remain?

Only 13 historic all-Black towns remain: Boley, Clearview, Langston, Redview, Taft, Brooksville, Grayson, Lima, Red Bird, Rentiesville, Summit, Tatums, Tullahassee, and Vernon. Boley and Langston still host Black rodeos, with Boley holding its rodeo every year on Memorial Day weekend, despite the town having declared bankruptcy in 1939, as reported by McAlester News-Capital.

According to NonDoc, the remaining towns face decreasing populations and have seen their schools closed and children shipped to other towns due to state laws forbidding the existence of small schools, often preventing the growth of future generations in the process.

However, the towns are still trying to make it. Tullahassee, for example. As covered by The Washington Post, while the town's population is only around 100 people, attempts have been made for decades to sell land to people who have become aware of the town's history and want to move there. These efforts include building properties to attract people with young families. Despite hostility from nearby white communities, the former town manager, Keisha Currin, started the company Black Towns Municipal Management to encourage investments into Oklahoma's all-Black towns.

Will there be new ones?

Despite their economic decimation, Oklahoma's all-Black towns have fought to survive and put down new roots. A new town called IXL was founded in 2001, notes the Oklahoma Historical Society. It was based on the community of IXL, which grew in the 1920s after a grant of $1,100 donated by the Julius Rosenwald fund led to the creation of a school (admittedly segregated) for children in the grades up to and including the eighth grade. The Rosenwald Fund further donated $900 toward a house for teachers, with the community also making financial contributions.

Although it has no solid commercial base, the town has since built a fire department and a fire station, and in 2001 (according to the State Historic Preservation Office), government buildings were constructed, housing a town council and an office for the mayor. The old schoolhouse was eventually pulled down in 2012 so the site could be converted into a community center, and a public park and two churches also became part of the fabric of IXL.

In 2010, IXL's population was recorded as 51.

Reparations and preservation

The history of segregation and the Great Depression meant that many of Oklahoma's all-Black communities found it financially untenable to run themselves. The refusal of white-run banks and farmers to give credit to or hire Black workers or businesses, and the historic acts of white violence against places like Greenwood, have led to calls for these communities to be compensated. As explained by NonDoc, some towns, such as Clearview, have often had to manage without electricity or running water.

As reported in The Washington Post, this has prompted a push for reparations from both public and private sources. The MORE Commission (Mayors Organized for Reparations and Equity) in Tullahassee has been trying to secure public money to rehabilitate old buildings and bring more private developers into the towns so as to increase the supply of available housing.

Other community organizations, such as the Coltrane Group, are keeping the towns' heritage alive by offering tours, taking advantage of the rising demand for tourism centered on Black experiences. The Coltrane Group holds tours of the state's all-Black towns five times a year, taking in major areas of historic interest like significant public buildings and the houses of previous well-known residents.

Overall, places like Tullahassee are promoting themselves as havens of safety in the face of modern-day racism and police brutality. It will be a long journey back to these towns' former glory. Yet, for many of these towns, what they lack in money, they make up for in hope.