Robert Fulton: The Man Who Changed America Forever With A Steamboat

Although the brilliant American engineer Robert Fulton didn't invent the concept of a steamboat, he perfected it, making the commercial use of safe, steam-driven ships finally possible.

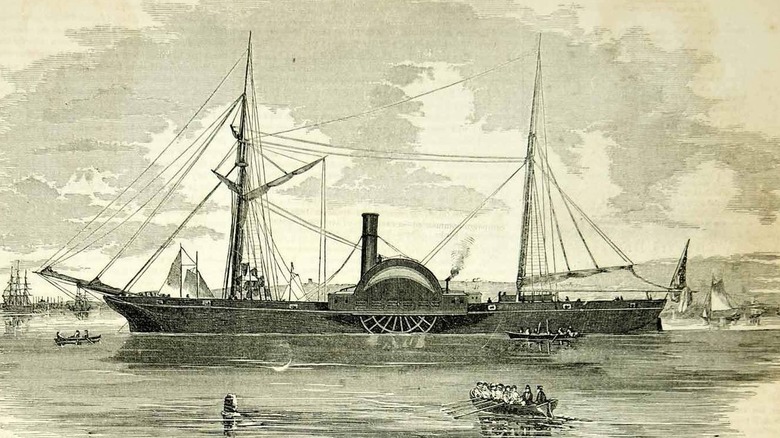

It was he who created the ideal design for the vessel using his own innovations on the steam engine; he used a flat-bottomed, square-sterned boat with paddle wheels on each side to propel it, as explained by PBS in its documentary "Who Made America." His creation revolutionized the transportation of both goods and people, since his vessel could travel against currents and winds; it therefore heralded the last glory days of the age of sail.

Fulton's formidable engineering genius was also responsible for the invention of, or innovations to, the dredging machine, the submarine, and its conning tower and bathometer, catamarans, and torpedoes, as related in the article Creative Combustion: Image, Imagination and the Work of Robert Fulton. A polymath from a very early age, Robert Fulton was known to have suggested improvements for many machines that he saw as a young man growing up. This endless desire to improve and perfect the workings of machines enabled him to become the renowned inventor who changed not only marine transportation but the nature of maritime warfare as well.

Robert Fulton was a born engineering genius

The man who would go down in history as a genius with his maritime inventions was born in the countryside near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1765. Drawn to the study of mechanics initially, Robert Fulton conducted his own experiments with mercury and bullets, becoming known as "Quicksilver Bob" as a teenager, as related in "Old Steamboat Days on the Hudson," by David Lear Buckman. Not noted for his academic prowess, he would wander into the shops of Lancaster and make suggestions for improvements to weapons after watching gunsmiths working, Buckman states. Incredibly, Fulton even worked on a prototype of a rocket, presaging his later invention of torpedoes.

However, his painstaking sketches of these various machines and inventions — which were necessary later when applying for patents and material support — as well as his apprenticeship as a miniaturist when he created small portraits, spurred him to embark on an artistic career in Philadelphia at the age of 17, according to Southern Lancaster History.

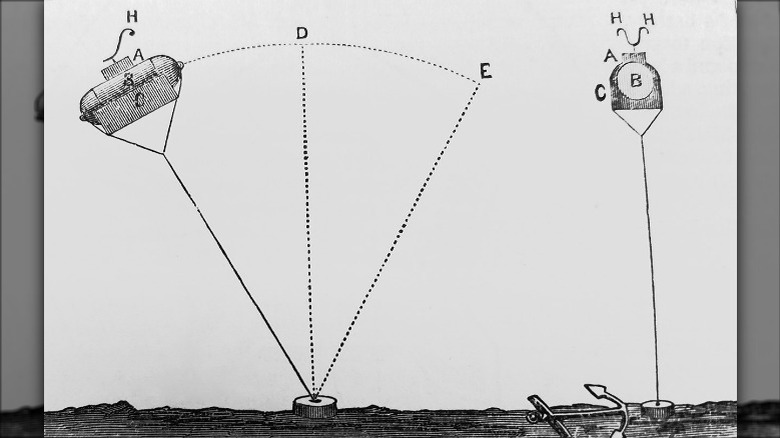

In his scientific study for the bathometer, his invention to gauge the depth of submarines, and his conning tower, the polymath's extraordinary self-portrait (pictured) shows himself peering through the tower's lens, as noted by Elizabeth Bacon Eager in her paper Creative Combustion.

Fulton was a gifted artist who painted a portrait of Benjamin Franklin

After Robert Fulton trained in the fine arts, he received a commission to paint a portrait of the iconic statesman and inventor Benjamin Franklin, according to PBS' "They Made America" — although tragically none of his early works survive. The great English painter Benjamin West reportedly wrote a letter of introduction for him, allowing Fulton entrance to artistic salons in London. Fulton painted many landscapes while living with West's family; however, his mind would continually turn to engineering, and he conducted a number of scientific experiments at that time.

As related in "Old Steamboat Days on the Hudson" and by Southern Lancaster History, before long, Fulton patented his design for a dredging machine for digging and maintaining harbors, and other inventions, including a marble cutter.

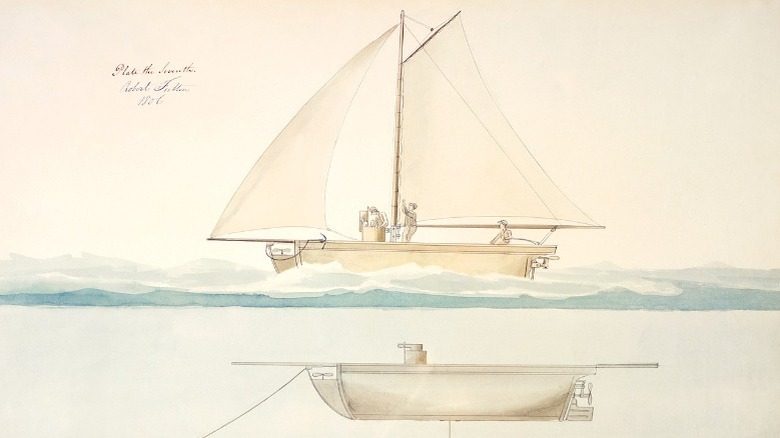

His impressive artistic gifts, as seen in this watercolor showing how his submarine — with collapsible masts — could also sail atop the seas, enabled him to create drawings and paintings that perfectly encapsulated his groundbreaking ideas for boats, torpedoes, and machines. He continued to paint throughout his life, even after returning to the United States and working on the creation of his steamboat, according to Princeton University, which holds several of his paintings.

Canal engineering led to Fulton's interest in steamboats

Despite his talent as a painter, Robert Fulton found himself drawn to more concrete endeavors by 1794. Perhaps because of his friendship with the Duke of Bridgewater, who had constructed his own canal according to Southern Lancaster History, Fulton turned his genius toward engineering "tub-boat" canals throughout Great Britain that used inclined planes, which were in development alongside traditional lock-operated waterways, even publishing a scholarly work titled "Treatise on Improvement of Canal Navigation."

Recognizing the possibilities in new methods of transportation and locomotion after seeing steam-propelled boats use individual paddles for propulsion, Fulton then directed his agile mind to the further development of a practicable steamship, contacting officials in both Britain and the U.S. to gauge their interest in his ideas, as related by ThoughtCo. Others had designed prototypes of the steamship, including John Fitch, whose vessels used oars rather than paddlewheels, and French inventor Claude de Jouffroy in 1776, with whom Fulton collaborated. Jouffroy had developed and put into practice the concept of a side paddlewheel, but neither pursued construction of further steamboats nor sought a patent for them, as noted by Universalium.

It was to be Robert Fulton who perfected the design, creating the new form of the vessel that would be ideally adapted to steam-driven propulsion.

Robert Fulton created a submarine for France

The idea of creating a workable submarine was foremost on Robert Fulton's mind after he arrived in France in 1797, as Napoleon rose as a military force, notes Southern Lancaster History. His mathematics and chemistry studies there formed a basis for developing submarines and torpedoes, which he would go on to create several years later.

Submarines were originally conceptualized back in 1546 by British mathematician William Bourne, Science Clarified notes, with an unsuccessful iteration called the "American Turtle" by inventor David Bushnell. Working for the French Directorate, Fulton successfully piloted his muscle-powered "Nautilus" for an impressive 17 minutes at a depth of 25 feet in the Seine on July 29, 1800, as PBS notes in its documentary.

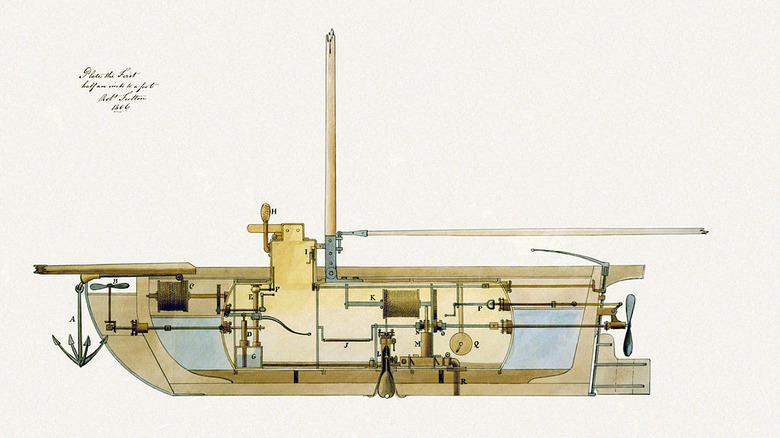

Despite this triumph, the French Navy viewed submarines as a stealthy and therefore dishonorable means of warfare, according to the USS Nautilus, declining any further part in producing what they called Fulton's "plunging boat." The conning tower, use of compressed air tanks, rudders, and compass-based navigation aboard the Nautilus — essential features of every submarine ever constructed after that time — have gone down in history as remarkable innovations on their own.

Fulton created the world's first torpedoes

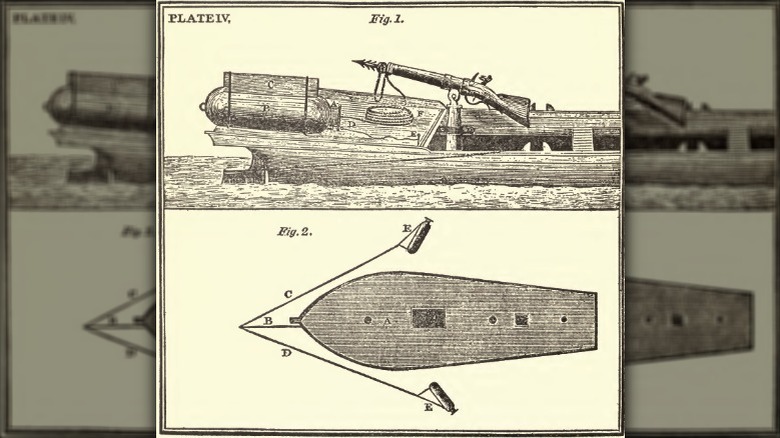

In 1802, Robert Fulton turned his mind toward constructing torpedoes, to be employed in warfare against Napoleon, who was at the height of his power. They were to be the world's first type of sea mine that was launched toward a target rather than the primitive mines that would be simply left floating for other ships to come upon during wartime, as the historians of the USS Nautilus explain.

In one of the most spectacular trials for the torpedoes for the British Navy, Fulton destroyed the 200-ton brig Dorothea on October 18, 1805, before an audience of Navy officials. Fulton's torpedoes were connected to cables; when the target traveled past he released the torpedo at the exact moment it would come into contact with its hull. Another innovation was that Fulton's torpedoes were weighted down so that they would remain underwater; this made them even more stealthy than traditional, floating sea mines, according to the USS Nautilus.

The destruction of the Dorothea cemented his reputation as an inventor and innovator. Incredibly, Fulton believed at the time that such weapons would bring an end to maritime warfare as it was known. He stated, "Should some vessels of war be destroyed by means so novel, so hidden, and so incalculable, the confidence of the seamen will vanish and the fleet [be] rendered useless from the movement of the first terror," as noted in the book "Robert Fulton and the Submarine" by William Barclay Parsons.

Robert Fulton's torpedo demonstration

Robert Fulton returned to the U.S. in the year 1806 to sink a U.S. Navy ship – a brig at anchor – as part of a demonstration of the use of torpedoes for the American Navy. Congress was so impressed with this new technology that it granted Fulton the then-princely sum of $5,000 to explore its use, according to a report on Fulton by MIT.

Fulton believed wholeheartedly that these fearsome new weapons would mean no less than "The liberty of the seas" and "the happiness of the earth," since they would pose such an incredible threat to enemies, as he wrote in the frontispiece of his book "Torpedo War and Submarine Explosions."

President Thomas Jefferson – another polymath whose own genius knew practically no bounds – likewise immediately recognized the tremendous import of these new weapons, stating they would change the nature of maritime combat forever. "I confess I have more hopes of the mode of destruction by submarine than any other," Jefferson wrote in a letter to Fulton in 1810, as reported by Lancaster Online, adding "Your torpedoes will be to cities what vaccination has been to mankind. It extinguishes their greatest danger." Of course, this has sadly proven untrue; neither man appeared to believe that any other nation would copy and employ the technology, making warfare exponentially more deadly, not less so.

Robert Fulton begins a revolutionary design for a steamboat

Hailed as a hero for his invention of torpedoes and a workable submarine, Robert Fulton was asked by President Jefferson in 1806 to work on creating American canals after his earlier engineering work in England. It was only three years after the American president had bought the vast lands of the Louisiana Purchase, and their rivers were ripe for commerce and trade. However, obsessed with perfecting the steamship, Fulton declined Jefferson's offer and set to work designing a vessel that could be powered by steam, yet be seaworthy and used for mass transport, as MIT states.

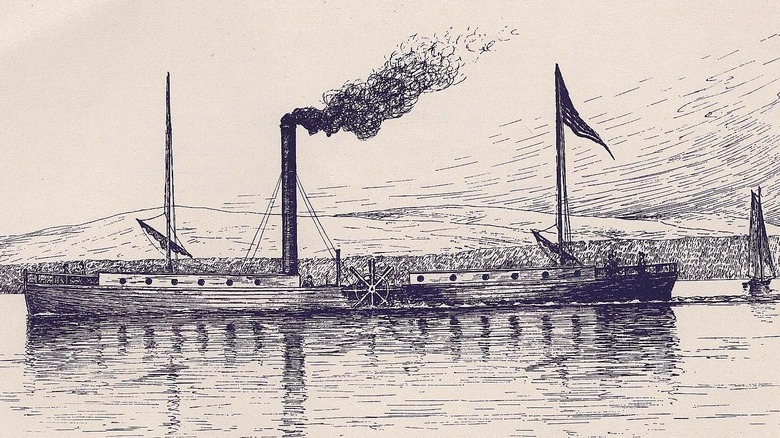

He used Watt's original steam engine – which had been constructed in 1765, the year Fulton was born — with added innovations of his own to create the perfect engine for the ship, and designed the vessel that would house this engine, taking into account the unique means of its propulsion. At 150 feet long and a mere 12 feet wide, the boat was a much slimmer version of the stout steamboats which would soon ply the Mississippi, loaded with cotton bales.

As PBS points out in its documentary on Fulton, he realized it must not have the heavy, deep keels of sailboats, which use them as a steadying force as they heel over in the wind; he decided, correctly, that a flat keel would be the ideal shape for this type of vessel, and that revolving paddlewheels would be the ideal means of propelling them from a squared-off stern.

The Clermont steams triumphantly up the Hudson River

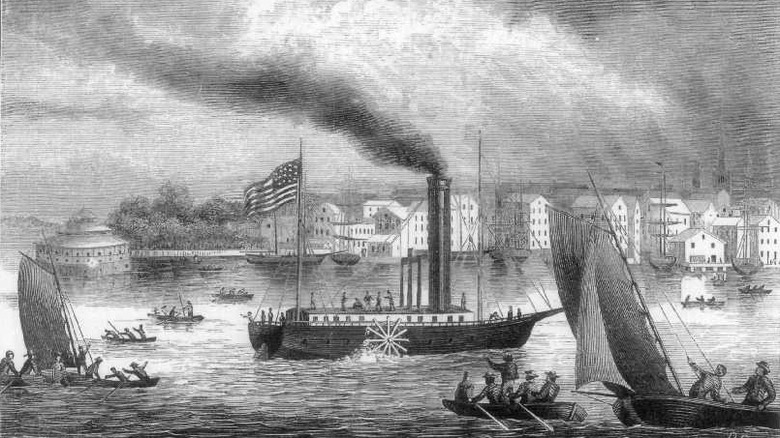

The 150-foot-long North River, referred to by his partner Robert Livingston, and the press, as the Clermont, was also called derisively "Fulton's Folly" by doubters; indeed, Robert Fulton himself acknowledged that its appearance, with its ungainly smokestacks belching black smoke into the sky, prompted "a number of sarcastic remarks," according to MIT's retelling of the story. However, with its 19 horsepower engine, using two side paddlewheels, it successfully sailed from New York City to Albany at a stately 5 miles an hour, completing a round-trip voyage in a total of 62 hours, on August 17, 1807. It was an unequaled triumph for the man whose engineering genius ranged far and wide.

The ship was clearly like nothing onlookers had ever seen; Kirkpatrick Sale, in his book "The Fire of His Genius: Robert Fulton and the American Dream," gave insight into how she appeared to them: "She was described in the night, to those who had not had a view of her, as a monster moving on the waters, defying the winds and tide, and breathing fire and smoke."

Fulton quickly received a patent for his steamship; competing companies soon created a Wild West-like atmosphere on the river, however, with numbers of steamboats plying the waters willy-nilly, playing chicken with each other. In the span of five years after the launching of the North River, Fulton was at the helm of a booming steamboat transportation business on the Hudson, as PBS relates in its documentary "They Made America."

The steamboat New Orleans explores the Mississippi River

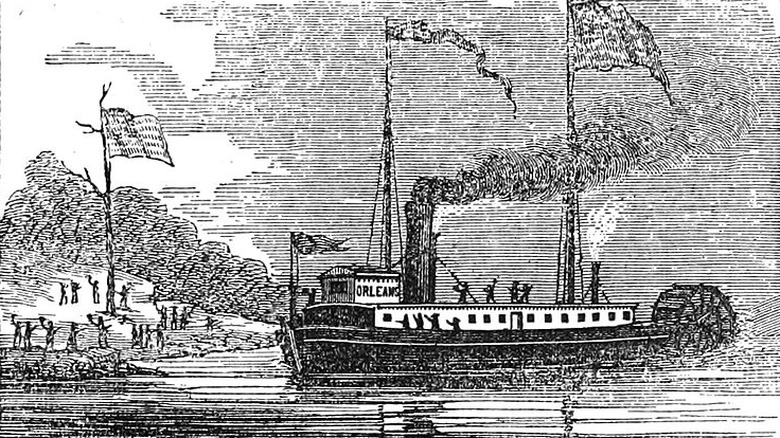

Robert Fulton then designed, constructed, and funded — along with his steamship partner Robert Livingston — the New Orleans, the iconic steamship that traveled down the Mississippi to that new American city soon after Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase. A seminal moment in American history, this enabled the mapping of hitherto uncharted territories along the Mississippi and opened up new transportation routes.

Setting off on October 20, 1811, and steaming an astonishing 1,800 miles down the Ohio and the Mississippi, the vessel proved that steamboats were capable of sailing down America's greatest navigable rivers when it arrived in triumph at New Orleans on January 10, 1812, as told by Leslie Przybylek of the John Heinz History Center. Along the way, she and her owners and builders — including Nicholas Roosevelt, the great uncle of President Theodore Roosevelt — overcame nearly insurmountable obstacles, including the Ohio River falls at Louisville, which had a drop of 26 feet.

By waiting until Spring and the rising of the waters, the New Orleans was able to continue on her journey of discovery. But her appearance and the sounds her engine made were startling to many onlookers, especially at night, with her coal-fired boilers bellowing smoke and brimstone, causing Louisville residents to rush to the docks in fear that an explosion had occurred. Captain Roosevelt invited the public to sail along the Mississippi once she landed at New Orleans, beginning the tradition of steamboat excursions there.

The world's first steam-powered warship

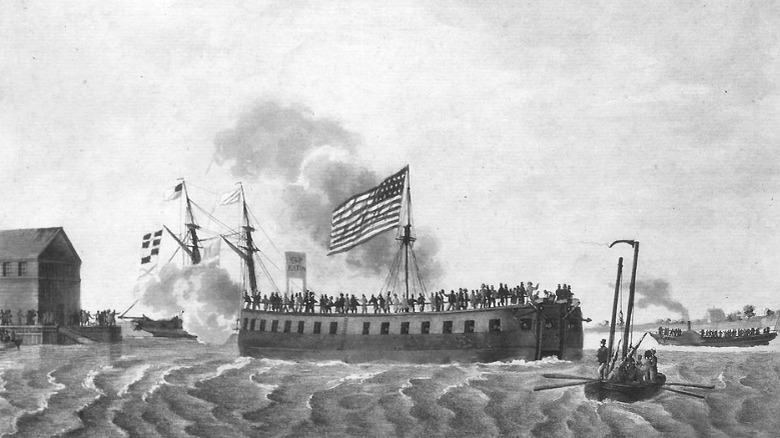

As related by the University of Houston, Robert Fulton also engineered the world's first steam-powered warship, the 150-foot-long, 60-foot-wide Demologos, Greek for "Word of the People," in a nod toward Fulton's democratic, anti-monarchist political leanings. Undoubtedly noting the vulnerability of propellers (the Achilles' heel of the Monitor and the Merrimac, which decades later would be the first ironclad ships used in maritime combat during the Civil War), Fulton created another major engineering innovation with this vessel. He successfully protected the ship's means of propulsion, its paddlewheel, by constructing a double hull on each side of it.

In effect, Fulton had created the modern world's first naval vessel in the shape of a catamaran. The Demologos — also referred to as the Fulton — proved successful in trials in the Summer of 1815, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command, but by then the War of 1812 was drawing to its close. Fulton's steam-powered warship was delivered to the U.S. Navy in June 1816 — after the untimely death of her creator — and was docked at the Brooklyn Naval Yard; tragically, its magazine exploded in 1829, killing 30 men and destroying the vessel.

The U.S. Navy named five ships after Robert Fulton

In 1814, construction began on Fulton's ship the Torpedo, aptly named for the newfangled weapons that were used against British warships in the War of 1812, but Robert Fulton died while it was being built. Due to his complete involvement in its construction, the workmen were unable to proceed after his death and the vessel was abandoned.

Fulton devoted himself to the promotion of the use of torpedoes to protect American harbors and waterways, including Baltimore Harbor and Lake Erie during the War of 1812; as Alan Rems states in his essay "Man of War," published by the U.S. Naval Institute, his offer was not taken up and they played no part in the defense of the country during those years. However, this may have spurred him on to create yet another new type of weapon, a submarine gun that would shoot ordinary artillery shells through the water. However, this too was ignored by the government despite Fulton's warm relationship with government officials — as was Fulton's own idea to nominate himself as Secretary of the Navy, despite being championed by Dolley Madison, the influential wife of President James Madison, who encouraged her husband to consider the candidacy of the brilliant inventor, as Rems notes in his story.

However, Fulton's genius was well-recognized by the U.S. Navy, which subsequently named no less than five ships after the brilliant inventor, including the USS Fulton, launched on June 12, 1901, and four others.

His inventions revolutionized shipping and naval warfare

Americans went into deep mourning when Robert Fulton died suddenly on February 24, 1815, at the age of 49, after saving a friend who had fallen through the ice of the Hudson River. Combining innovations in steam engines, ship design, and weaponry, and making all his brilliant inventions workable, as PBS notes in its series "They Made America," Fulton enabled no less than a revolution in shipping, transportation, and naval warfare.

He was well aware of the power of the many machines he invented; he acknowledged this long before he designed his warship for the United States Navy. As Elizabeth Bacon Eager notes in her essay Creative Combustion, writing to British government officials when he was trying to garner support for his torpedoes, Fulton stated, "Much experience has made me conscious of the engines I possess."

Since the brilliant inventor of so many things, both destructive and constructive, passed away so young, the world will never know what he thought about the ever-deadlier progression of warfare as time went on, or whether he regretted marketing his war machines to the highest bidder. It may have taken a toll on him that only his oldest friends realized, Eager states. As Robert Fulton's mentor, the noted British painter Benjamin West, said in his eulogy, "He was destroyed by the fire of his own genius and the never-ceasing activity of a vigorous mind."