The Untold Truth Of The Royal Air Force

The British Royal Air Force (RAF) uses air power to protect the United Kingdom and advance its interests, with the RAF defining this as "The ability to project power from the air and space to influence the behavior of people or the course of events." However, as important as the RAF may be to the U.K. today, it is most noted for its actions in the 20th century.

In the Second World War, the RAF was famously vital to the United Kingdom's security during the Battle of Britain, which pitted the nation's Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires against the might of the German Luftwaffe, with its Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, and Messerschmitt Bf 109s (via History Hit). Prime Minister Winston Churchill's praise for the RAF crews perfectly articulated the gravity of their service: "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few."

The Battle of Britain may have been the RAF's "finest hour," but it was not its only hour. For more than a century, the RAF has been involved in numerous conflicts, including the First World War, Second World War, Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, the Suez Crisis, the Falklands War, and the recent conflicts in Iraq, Libya and Afghanistan. Here is the untold truth of the Royal Air Force.

The Royal Air Force was preceded by the Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Air Force (RAF) was not the first British organization to use aircraft in a military context. That distinction goes to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which was established in 1912 (via the National Army Museum). The first few years of the RFC were rather innocuous, with pilots and technicians spending most of their time testing their aircrafts' capability in flight and reconnaissance — namely aerial photography and artillery spotting.

During the First World War, which raged from 1914 to 1918, it was artillery spotting that would prove to be the RFC's most important capability . According to historian Lee Kennett, writing in "The First Air War: 1914-1918," the RFC took over 500,000 photographs of enemy trenches, artillery positions, and other salient locations during the war. These were vital in directing British artillery crews, who typically engaged in "indirect fire," which meant that they could not otherwise see their target (via RAF History Society).

The RFC's planes were not so effective in an offensive capacity, though not for want of trying. Historian Keith Robbins wrote in "The First World War" that, for four months in 1915, the RFC launched 141 bombing raids, dropping some 1,000 bombs. However, a study in June 1915 found that just three of these raids had been successful. The RFC were quick learners though, and by the spring of 1918, it was succeeded by the RAF, which would use this experience to its advantage.

The RAF was the world's first independent air force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) was formed on April 1, 1918, while the First World War was still raging. It was the world's first air force that was fully independent of the Army and Navy (per Britannica), and it had little time to waste. According to History, a force of Bristol F.2B fighters took flight on the very day of the RAF's inception.

By November 1918, the RAF had achieved air superiority, boasting a force of over 22,000 aircraft, and some 300,000 officers and airmen. The Royal Air Force made such an impression on popular sentiment that in 1923, a monument to the RAF's fallen was unveiled in Central London. Further inscriptions were added in 1946, following the terrible losses of the Second World War (via RAF).

Incidentally, one of the aforementioned 300,000 officers and airmen was Henry Allingham, who would live to be not only the last living founding crew member of the RAF, but also the oldest person in Britain. He died in July 2009, aged 113 (via BBC).

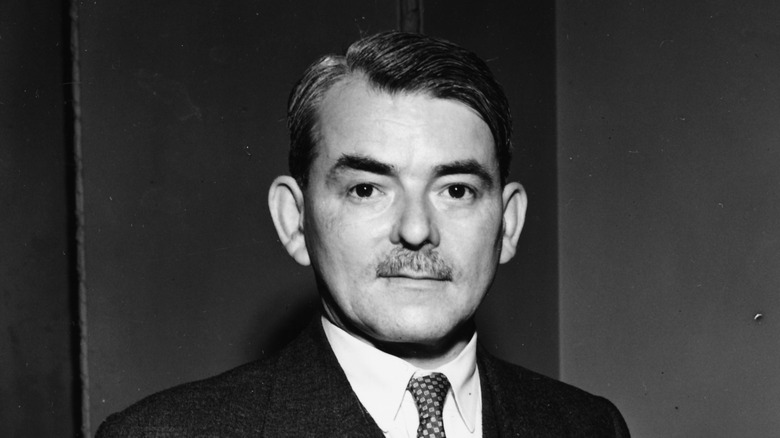

RAF officer Frank Whittle invented the first jet engine

During the interwar period between WWI and WWII, Frank Whittle invented the jet engine (via BBC). Born in the Midlands of England, Whittle had excelled in both an RAF apprenticeship and a Cambridge University engineering course, before he focused on the jet engine. Biographer Duncan Campbell-Smith said, "Whittle's jet engine design was a paradigm shift ... To understand a jet engine required a different understanding of aerodynamics and thermodynamics." However, despite Whittle's remarkable innovation, authorities were skeptical. The U.K. government rejected his ideas in 1929, although he did secure private funding, allowing Whittle to establish a manufacturing company called Power Jets.

In 1940, the British government finally supported jet engine development. However, they didn't contract Whittle's company, choosing instead a rival program by Rover, the British car manufacturer. This meant that Whittle had to contend not only with the government, which he described as like "wading through treacle," but also had to answer to Rover executives, who constantly meddled with his design.

The stress of the job and the war, which destroyed his home city of Coventry, seriously affected Whittle's mental health. "I remember him turning from a very jolly chap into somebody who became rather unwell," said his son Ian. Yet Whittle did not lose his motivation, and despite the "constant lack of interest, constant discouragement, and constant apathy," the genius engineer managed to create the W1 jet engine — which was so advanced that modern jet engines share much of the technology.

The RAF implemented Robert Watson-Watt's radar technology

The jet engine may not have played a central role in Britain's air power during the Second World War, but radar technology certainly did. Derived from an acronym, "radar" stands for radio detection and ranging, and the technology was pioneered by Sir Robert Watson-Watt, a Scottish scientist based at the National Physical Laboratory in Teddington, England (via Britannica).

It was in Teddington that Watson-Watt discovered the ability to use radio waves for detecting aircraft, a phenomenon he explained to the British government in February 1935. Soon afterwards, he was demonstrating his discovery, and by July 1935, Watson-Watt's technology was detecting aircraft some 90 miles away, and with great consistency too. The British government installed radar systems across the United Kingdom, chiefly along the South-East coast. There were 18 systems at the war's outset in 1939, and by 1945 there were 53. According to the Imperial War Museum, these installations were a part of the Dowding System, which coordinated the British homeland's defensive and offensive capabilities.

Watson-Watt's technology was one of the most important components of the Dowding System, which saved countless lives and conserved vast amounts of military equipment. Without radar, the likelihood of a planned land invasion of Britain from the German-occupied European continent, codenamed Operation Sealion, would have been much greater (via RAF Museum).

The Luftwaffe never got close to defeating the RAF

The Battle of Britain was a fierce test of the RAF's capabilities. However, the Luftwaffe did not come close to destroying Britain's fleet, despite the greater strength of the German force in the summer of 1940 (via History).

History Hit mentions the popular belief that Britain barely survived the Battle of Britain, yet in reality the RAF proved to be a formidable enemy, decisively stalling the Third Reich's plans for European domination. Despite Germany's swift victory in the Battle of France, the odds were always stacked against the Luftwaffe: To secure air superiority, German air crews needed to inflict a high casualty rate on the enemy, with as little reprieve as possible. However, the Luftwaffe only achieved higher kills than losses on five occasions — which was not enough to diminish the RAF's strength.

Furthermore, the RAF's Spitfires and Hurricanes were manned not only by British pilots, but also by experienced veterans from Poland, France, Czechoslovakia, and other nations. According to Historic U.K., the Polish pilots operated in two dedicated RAF squadrons: 302 'Poznan' Squadron, and 303 'Kosciuszko' Squadron. The Polish fighters proved to be very effective, especially those of the 303 Squadron, who downed 126 German planes — higher than any other squadron of the battle. By October 1940, the RAF had increased its capacity by 40%, while the Luftwaffe's strength had depleted by some 30%.

At first, bombing was Britain's primary weapon during WW2

For the first few years of the Second World War, Britain's bombers were the main weapon used against Nazi Germany, after the British Army was forced to evacuate the European continent via Dunkirk in May 1940. This was solidified after the Dieppe raid on 19 August, 1942, which saw a seaborne Allied force thrown back from the French town, during a disastrous attack on German positions (via BBC).

The Allied armies would not be ready to cross the English Channel until June 1944. So, in the meantime, Royal Air Force (RAF) bombers continued to fly over German towns and cities, wreaking havoc. According to "Why The Allies Won," these attacks drained German resources on the vital Eastern Front — the theater for some of the Second World War's largest and most decisive battles (via Britannica). For example, the bombing campaigns of the RAF and its allies caused German forces to redistribute two-thirds of its fighter aircraft, and approximately 75% of its 88 mm guns, the latter of which were essential to combat the Soviet Union's vast fleet of T-34 tanks.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill always recognized the importance of Bomber Command. In September 1940, as the Battle of Britain neared its end, Churchill wrote, "The Navy can lose us the war but only the Air Force can win it ... The Fighters are our salvation ... but the Bombers alone provide the means of victory."

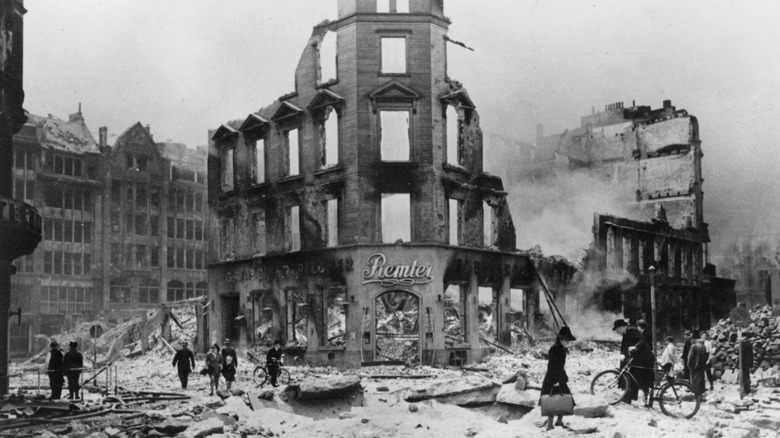

The bombing of Hamburg killed more people than the entire London Blitz

Codenamed Operation Gomorrah, the bombing of Hamburg in July 1943 killed some 40,000 people, around the same as the entire London Blitz — which lasted months longer. The attack began with a raid on the night of July 24, and was followed by several day and night raids by British and American forces (via ThoughtCo).

The most devastating raid occurred on the evening of July 27, when over 700 Royal Air Force planes attacked an already crippled city. Historian Malte Thießen noted in The Local that, "It was a very hot week, the city was dried out." This would prove to be deadly, as the oxygen was absorbed by the RAF's incendiary bombs and fomented a ferocious firestorm, which surged through the city with such force that it uprooted trees and swept civilians off their feet, throwing them into hellish oblivion.

"My dear sir, this is a military and not a civilian war," Winston Churchill had remarked to a fellow politician who was seeking revenge for the London Blitz. However, attitudes had shifted by 1943, and so had policy, which adjusted to inflict maximum damage on the German people. According to National Geographic, British and American forces researched German construction methods to determine how best to destroy the city. They succeeded, inflicting the worst aerial bombardment the world had yet seen — though this precedent was soon surpassed by other terrible engagements of the Second World War.

Bomber Command's destruction of German cities became distasteful — even for Churchill

In February 1945, the Royal Air Force's Bomber Command attacked the German city of Dresden, ravaging the beautiful Medieval settlement and killing up to 25,000 people. Such a brutal attack so late in the war was meant with concern by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who wrote, "It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror should be reviewed."

A United States report in 1953 estimated that some 50% of Dresden's residential buildings were destroyed, along with 23% of the city's industrial area, which was razed to the ground. The Nazi regime was quick to propagandize the attack, claiming it had killed 200,000 people — which was an almost tenfold exaggeration — and that Dresden had no strategic or military value whatsoever. That was disputed by the Allies, who argued that the attack disrupted communication facilities that could have been used against the advancing Soviet army, according to History.

In the 1950s and '60s, the Royal Air Force ruled the skies

Following the Second World War, British engineers and scientists were world-leaders in jet aviation technology. As James Hamilton noted, the Second World War had caused Britain's aviation industry to grow at a tremendous rate, supplanting just about every other industry in the country. This continued in the immediate post-war years, with the support of the new prime minister, Clement Attlee.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) regularly displayed its aviation prowess at the Farnborough Airshow, which debuted planes such as the Avro Vulcan Bomber, one of the most iconic planes in British history, via Imperial War Museums. Here, records were set too: On March 10, 1956, RAF pilot Lionel Peter Twiss flew a Delta II at an average speed of 1,132 mph — a new world record, according to Guinness World Records.

It wasn't all pride and progress, though. During the 1952 Farnborough Airshow, a RAF De Havilland jet broke up in midair, killing the two pilots. As the crowds watched in horror, the debris careered into them, killing a further 28 people (via BBC). Despite this and other setbacks, British engineering concluded the 1960s with another aviation game-changer: the Harrier Jump Jet. Designed by Hawker Siddeley, the Harrier allowed pilots to, in the words of Lord Tebbit, "stop and hover like a kestrel," owing to its vertical takeoff system known as V/STOL.

The RAF launched some of the longest bombing raids in hostory

During the Falklands War in 1982, the Royal Air Force launched Operation Black Buck, which were the longest bomb raids in history at the time, per Imperial War Museums. The conflict began on April 2, 1982, when an Argentine force invaded the British Falkland Islands, a craggy archipelago in the South Atlantic. Argentina's military dictatorship — led by Lieutenant General Leopoldo Galtieri — was firmly rebuffed by U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who declared the islands and a 200 mile zone around them a war zone (via Britannica). A British task force, comprising two aircraft carriers and two troop ships, was dispatched from Portsmouth harbor and sailed to the Falklands via the British territory of Ascension Island.

On April 30, two Vulcan bombers were assigned to target the runway at Port Stanley — the Falklands' capital — flying from and returning to Ascension Island, located over 3,000 nautical miles from the Falkland Islands (via RAF). This epic mission required the pilots to not only cover some 6,600 nautical miles and refuel in midair, but to then bomb a military target after some eight hours of non-stop flying. The stakes couldn't have been higher, but on the morning of May 1, 1982, after a true white-knuckle ride, a British Vulcan entered the Falklands war zone and successfully hit its target. The RAF would go on to launch seven of these Black Buck raids, five of which were successful.

Today, the RAF is still one of the world's most powerful air forces

According to the World Directory of Modern Military Aircraft (WDMMA), in mid-2022 the Royal Air Force (RAF) was ranked as the 11th most powerful air force in the world. Using the WDMMA's "True Value Rating" (TvR), the RAF's ranking TvR score of 55.3 placed it below the French Air Force, which was awarded a TvR of 56.3, and above the South Korean Air Force, which was given a TvR of 53.4.

The top-five is dominated by various branches of the United States military, and soaring over all others is the United States Air Force (USAF), which was given a TvR of 242.9 — a full 100 points higher than the second-placed United States Navy, rated at 142.2.

The disparity between the Royal Air Force and the United States Air Force is marked, to put it mildly. For example, the RAF's fleet stands at 479 aircraft, whereas the USAF boasts 5,209 aircraft. However, these statistics are — for the most part — peacetime figures. Consider that by the end of the Second World War in May 1945, the RAF's fleet grew to some 9,200 aircraft (via Hilary St George Saunders): We can only guess the numbers an equivalent war in modern times would produce.