How Hollywood Looked The Year You Were Born

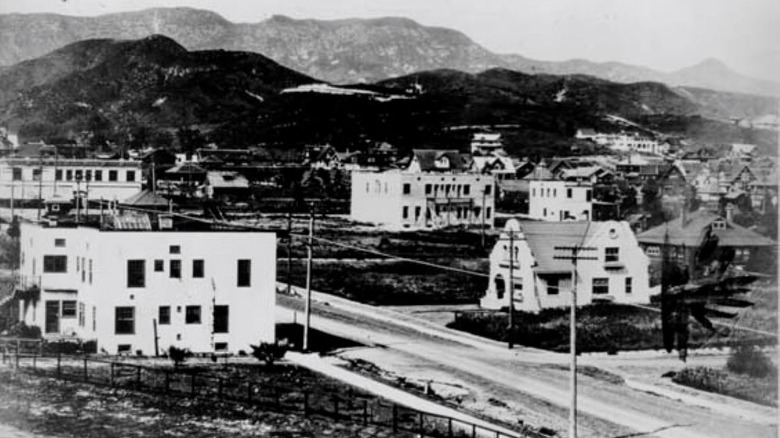

Hollywood is not much older than the oldest person in America, who, at the time of this writing, is 104-year-old Bessie Hendricks of Iowa. Bessie, according to the Gerontology Research Group, was born in 1907, just three years after Hollywood was incorporated as an upscale Los Angeles neighborhood (per History). By then, the future movie mecca was already finishing up production on a short film titled "The Count of Monte Cristo." Premiering in 1908 and running about 14 minutes long, it was Hollywood's first film. Notably, parts of the movie were also filmed in Laguna Beach and Venice.

The "Saga of the Sign," a book published by the Hollywood Sign Trust, explains that the Selig company originally began filming "The Count of Monte Cristo" in Chicago. Bad weather, however, drove the production crew to sunnier skies in California. A second film, 1910's "In Old California," was the first movie to be shot entirely in Hollywood, according to Academic. What happened to Hollywood as Bessie Hendricks and others came along during the town's fledgling years? Read on to see what Hollywood was up to the year you were born.

1887 to 1910: An early history of Hollywood

Way back in 1853, according to History, the future site of Hollywood was marked by nothing more than an adobe building. During the 1880s, says Curbed magazine, Harvey and Daeida Wilcox moved to Los Angeles and purchased 120 acres of nearby land. In 1887, Harvey filed a town plan for Hollywood. Unfortunately, he died in 1891, but by 1900 there were 500 people calling Hollywood home, according to Smithsonian magazine. Two years later, real estate developer H.J. Whitley opened the Hollywood Hotel. Daeida, however, just wanted a quiet but trendy Christian, non-alcoholic neighborhood. And for a while, she got it.

So how did the film industry take root in Hollywood? Word eventually got out about the filming success of "The Count of Monte Cristo." Back in Chicago, early movie producer William Selig (who has his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame), decided to move his studio to Edendale, a Los Angeles suburb just a few miles from Hollywood. Then, in 1910, the Los Angeles Almanac confirms that the California Motion Picture Manufacturing Company set up shop in Long Beach. The decision not to settle in Hollywood was understandable. The city had grown to 5,000 people, and a water shortage in Hollywood necessitated becoming a part of Los Angeles.

1911 to 1915: Hollywood goes on the Big Screen

Hollywood eventually won its spot in the film industry. Producers back east were inspired by "The Count of Monte Cristo," and were having issues with the father of film himself, Thomas Edison. The Los Angeles Almanac confirms that from his New Jersey studio, Edison created the Motion Picture Patents Company for his film equipment and sued those trying to use it for commercial gain. Producers skedaddled to far-off California, where the Nestor Film Company became the first film studio to actually make Hollywood its home in 1911 (per the Oakland Tribune). Soon there were no fewer than 15 studios in and around Hollywood.

In 1913, another new studio in Hollywood was owned and operated by Cecil B. DeMille. The future movie mogul partnered with Sam Goldwyn and others to film "The Squaw Man," a moderately successful film about a British officer who tries ranching in the West. Much of the film, says Britannica, was shot near Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street. But the biggest hit to come out of Hollywood was DeMille's "Birth of a Nation" in 1915, which Internet Movie Database says was filmed in 16 different locations throughout Southern California.

How the town's founder Daeida Wilcox felt about all this is moot; Find A Grave confirms she succumbed to cancer in 1914.

1916 to 1926: The Silent Era in Hollywood

By 1915, says Britannica, Hollywood was chock full of studios like Columbia Pictures, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount Pictures, Twentieth Century Fox, Warner Brothers, and a plethora of others. Film historian Tim Dirks elaborates further, telling how Universal Studios bought out the Nestor Film Company. Universal was not only the first major studio of its time but also produced a number of adaptations straight from classic literature. Then came "the vamp," a character created by Fox Film Corporation whose star, Theda Bara (pictured), appeared in 1916's "A Fool There Was" and became the first real sex symbol on the big screen.

It must be pointed out that films during the late teens and early '20s were silent — playing instead to music and/or displaying "shots of printed text" as viewers watched, verifies the National Museum of American History. Without dialogue, actors like Bara employed a more "physical process" to convey the mood of their characters, confirms the Video Caption Corporation. This was especially important during WWI, when Encyclopedia says filmmakers conveyed the need for "practical patriotism." That aside, however, Theda Bara and others like her indirectly created a modern woman. She was known as the "flapper" who, History explains, encouraged women to exhibit "economic, political, and sexual freedom," as well as the right to vote.

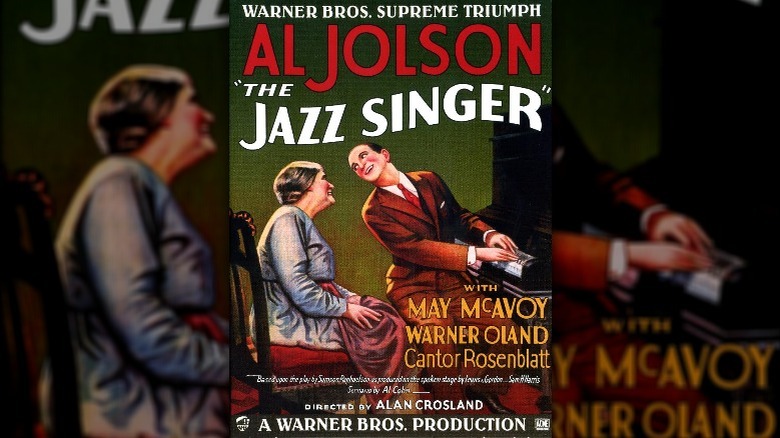

1927: The Talkie takes Hollywood

American film producers were no dummies. Most kept an eye on trends in the film industry, especially after Dr. Lee DeForest developed the Audion 3-Electrode Amplifier Tube, one of the earliest sound systems, in 1923 (per Encyclopedia). The newfangled gadget began making its way into theaters across America as movie producers worried: how expensive was this thing, anyway? Finally, Warner Brothers, just a small operation at the time, took the bait and purchased the Vitaphone, which Britannica describes as a "sound-on-disc system." The Vitaphone was first used in a 1926 production of "Don Juan" but only featured music.

Then came "The Jazz Singer" in 1927, which used the Vitaphone for musical performance scenes, but also for dialogue. It was well-received. Oxford's Donna Kornhaber writes that this leap in the movie industry effectively put an end to the silent film era. Still, there were plenty of bugs to work out. Central Casting, a well-known casting agency for nearly a century, confirms that wiring for sound was expensive and lengthy. Also that actors and extras and cameramen had to get creative in order to limit their movements and noises around sensitive microphones (check out 1952's "Singing in the Rain," which is great fun and explains this perfectly).

1928 to 1932: The era of Hollywood scandals

The glitzy and glamourous lifestyles of Hollywood were bound to catch up with someone, sometime. Vanity Fair quotes actor David Niven as saying that con artists, crooks, and "a hotbed of false values" dominated the scene. By the late 1920s, avid fans of Hollywood rags had already read about a few highly-publicized scandals that involved actors and actresses of the silver screen. There was, for instance, flapper actress Olive Thomas, whom author James Stewart writes overdosed in 1920. And in 1921, America was shocked when actor Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle (pictured) was accused of the rape, and subsequent death of, actress Virginia Rapp. Smithsonian magazine confirms Arbuckle was acquitted, but his career was ruined.

Then there was William Haines, whom the Harvard Crimson reveals was gay. Haines refused to hide that fact, making for lots of Hollywood whispers before he eventually left the movie industry. But one actress's lonely death went beyond the sneering and jeering from Hollywood tabloids. She was actress Peg Entwhistle, a depressed and distraught actress whom "The Saga of the Sign" verifies died by suicide at the Hollywood sign in 1932. Instead of reflecting on what the entertainment business did to her, many thoughtlessly referred to her as "The Hollywood Sign Girl."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

1933 to 1939: The night the lights went out in Hollywood

Today, the famous Hollywood sign remains symbolic of the town where the rich and famous gather. But did you know that it was originally intended as a real estate advertisement? History confirms the 45-foot-tall sign that was erected in 1923 originally read "Hollywoodland" as a way to advertise lots for sale. At night, 4,000 lightbulbs flashed the words "Holly," "Wood" and "Land" separately, and then as one word. By 1933, however, the sign and the rest of America were in the throes of the Great Depression. "Sagas of the Sign" explains that the Hollywoodland sign property was sold to the M.H. Sherman Company, which soon found that maintenance and lighting were expensive. For the first time in its history, the lights ceased to illuminate the sky at night.

Thankfully, Hollywood itself remained fairly unscathed by the Depression. Going to the movies proved a viable escape from the issues at hand. Most theaters acquiesced by charging a modest dime or a quarter for admission, or sometimes even accepted glass milk bottles in kind, says the Kennedy Center. Here, appreciative Americans could forget their misery for a bit. Feelgood films produced during this time, according to the Internet Movie Database, included "Modern Times" and "City Lights" (both starring Charlie Chaplin), "Gone With the Wind," "It Happened One Night," and "The Wizard of Oz."

1940 to 1950: Hollywood's war era

By 1940, according to Encyclopedia, the Golden Age of Hollywood had peaked. Big studios like Fox, MGM, Paramount, United Artists, Universal, Warner Brothers, and others had pushed out smaller producers. Concordia Memory Project's Maria Tommerdahl writes that during WWII, film became the best media to boost morale among Americans. Still, there were some scary times. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, historian Randy Young told CBS News, the FBI suddenly appeared in Hollywood and busted a group of Hitler supporters who had built a secret, $4 million military haven clear back in 1933.

Hitler's secret "bunker" scared people plenty. So when a Japanese sub appeared on the West Coast in 1942, says History, outright paranoia led Los Angeles residents to believe they were under fire on a February night. Some claimed a Japanese airplane had crashed in Hollywood. Only later were the sounds of shots being fired attributed to "friendly fire," says "Saga of the Sign." Hollywood got back to business, and in 1947, the Hollywoodland sign was donated to the City of Los Angeles, which removed the word "land" and repaired what was left. But darker days were coming. That same year, author Tony Williams writes in "American Cinema of the 1940s," President Harry Truman declared war against communism, which would soon trouble Hollywood.

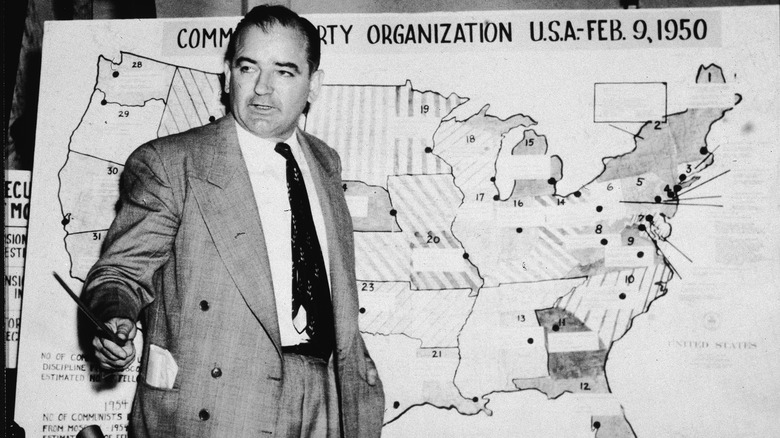

1950 to 1960: Hollywood during McCarthyism

Although WWII ended in 1945, a different sort of enemy attacked Hollywood. They called it "McCarthyism," wherein Senator Joseph McCarty began accusing certain Hollywood talent of being communists beginning in 1947, according to Biography. Nobody was safe; a number of well-known writers and actors were put on trial by the House Un-American Activities Committee. History names seven artists – actor Charlie Chaplin, actresses Lee Grant and Lena Horne, writer Dashiell Hammett, folksinger Pete Seeger, screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, and actor/director/writer Orson Welles as being outright accused of communism between 1947 and 1952 and "Blacklisted." Some were jailed.

Even comedienne Lucille Ball was accused of registering as a communist, which she did back in 1936 in an effort to "appease her socialist grandfather," according to the Washington Post. Many artists' careers were ruined, says Stanford Business, as well as those they worked with. The employment of actors could drop as much as 20% if they had previously worked with someone on the Blacklist. By 1954, the government had enough of McCarthy, who now accused anyone who displeased him of being a communist. "Have you left no sense of decency?" attorney Joseph Welch fired at McCarthy (per Britannica), after which he was formally censured by other senators. McCarthyism was over, and the senator died in 1957.

1958 to 1969: The Sixties were sad for Hollywood

By 1957, says Life magazine, there were so many new activities for Americans (bowling, golf, stereos, etc.) that movie theater profits were declining. Hence, Hollywood was embarking on "an incredible face lifting" in order to draw audiences. Life called it "New Hollywood," but the change was difficult. Box Office Pro explains that issues with pay rates and censorship, combined with the Vietnam War and younger audiences, added to the trouble. On top of that, says "Saga of the Sign," Hollywood was now downright crowded, and both residents and film producers were relocating to the San Fernando Valley.

Then, in 1964, along came the Whisky a Go-Go, a small but mighty live music club on the Sunset Strip. The Whisky a Go-Go was a trendsetter, a fresh and novel scene in Hollywood that attracted teens and 20-somethings. And it got producers thinking. Beginning in 1967, says Britannica, film studios stepped up to the plate and began turning out fresh, lively, and sometimes violent movies that appealed to younger audiences. "Bonnie and Clyde" came out in 1967, followed by "The Wild Bunch" and "Easy Rider" in 1969 and "M*A*S*H" in 1970. And all of them fit the rebellion movement being embraced by the younger generation.

1970 to 1978: A new sign and a new era for Hollywood

Hollywood is indeed one tough old gal. Although Rotten Tomatoes lists over 140 don't-miss movies during the '70s, hardly any of them were filmed in Hollywood. "Saga of the Sign" says that the only major studio there by 1970 was Paramount. Even so, restorations began anew on the Hollywood sign in 1973. One August night a canvas bearing an image of rocker Leon Russell was found draped over the "D," with the words "Save The Sign." Los Angeles got the hint and designated the sign a Historical-Cultural Landmark.

Nostalgia over saving the Hollywood sign didn't stop pranksters like art student Danny Finegood from celebrating the decriminalization of marijuana in 1976 by changing the letters on the sign to read "Hollyweed," writes Michael Darling of Southern California Public Radio. But it did inspire Playboy magazine founder Hugh Hefner to host a benefit for the sign in 1978, at which rocker Alice Cooper and others donated over $250K to replace it, says History, as tourists showed a renewed interest in Grauman's Chinese Theater (pictured), the Hollywood Walk of Fame and other attractions. Beginning in about 1978, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the new and improved Hollywood came to be referred to as "Tinseltown."

1979 to 1986: Movies became a top-dollar industry

Although few films were shot there by the 1980s, Hollywood remained associated with the movie industry. Tim Dirks points to producer Don Simpson, who wisely began appealing to younger generations. Movie plots were simple, flashy, and quick-moving, with memorable soundtracks. America loved them, to the extent that Rolling Stone easily qualified 100 films as the "greatest movies of the 1980s." Hollywood itself, however, was now the antithesis of the very films that made it great. Photographer John Humble shot numerous rundown, smoggy Los Angeles neighborhoods for Huck magazine. Coupled with Humble's stirring images are amateur films on YouTube showing that Hollywood Boulevard was jammed with traffic, cramped old buildings, and hundreds of outdated signs looming over the street.

Fortunately, help was on the way. In 1984, the city of West Hollywood was founded. The Sunset Strip was revitalized as a trendy, updated scene. The silent film stars and celebrities from the Golden Age were replaced by famous bands and a unique populace that included artists and musicians, as well as gender-diverse residents. Hollywood's most historic buildings were rehabilitated. Jack Smith of the Los Angeles Times was mighty impressed when he happened to visit the historic Hotel Roosevelt in 1986, which had been restored to its original grandeur at a cost of $35 million.

1986 to 2000: Hollywood was the place to be

As the late 1980s rolled towards the 1990s, the movies just kept coming. Vents magazine's Ryan Vandergriff explained that movies during that era covered such important topics as coming of age, finding oneself, bullying, gender confusion, love, and death. Writer Rebecca Nicholson called the 1990s Hollywood's "fairytale decade," wherein a new bunch of genres developed to encompass a bevy of subjects. Viewers were impressed by a new generation of young actors, coupled with young directors like Spike Jonze and Quentin Tarantino who made life seem grand and funny ... at least on the silver screen.

Plenty of movie buffs embraced the rebellious films of the '90s as a way to find strength and humor in their own lives. In her 2019 program "Nineties: Young Cinema Rebels," U.K. programmer Anna Bogutskaya showed how both movies and television influenced "the decade's rule-breakers and rebels." Hollywood reflected that too, with photographers like Randall Slavin capturing the pre-cellphone era and candid shots of young actors like Jennifer Aniston, Leonardo DeCaprio, Jennifer Garner, and Paul Rudd partying down in the local nightclubs. But there was a dark side to Hollywood nightlife, too. Hard drugs and alcohol contributed to the deaths of musician Kurt Cobain, comedian Chris Farley, and actor River Phoenix, the latter of whom died on the sidewalk outside of The Viper Room nightclub (per History).

2001 to today: The era of do-overs

With the onset of 2000, the movie industry seemed to run out of great ideas, inspiring them to look back at their successes. Thus, the remake was born, wherein producers took an old film and hopefully make it better with a new film. Metacritic cites 27 remakes between 2000 and 2011 alone, but they weren't all great. "King Kong," "Ocean's Eleven," and "True Grit" did well. "Mr. Deeds," "Prom Night," and "Rollerball" did not. Even so, Hollywood was still drawing tourists. The land around Hollywood's own old glory, the Hollywood sign, was saved from developers and protected in 2002, says History.

Far below the sign, however, vendors selling food, tickets, and tours on the streets were becoming bothersome. "Hawkers pushing their goods and forcing themselves on to you," wrote one visitor on Tripadvisor in April 2018. "Overall felt dirty." People spoke and the city listened; just a few months later, CBS News reported that new laws would prohibit street vendors from blocking sidewalks. Today, over 50 million people visit Hollywood each year says the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, whose website contains all sorts of events and entertainment to see. If you go, be sure to also check out the West Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, too, so you get the whole picture.