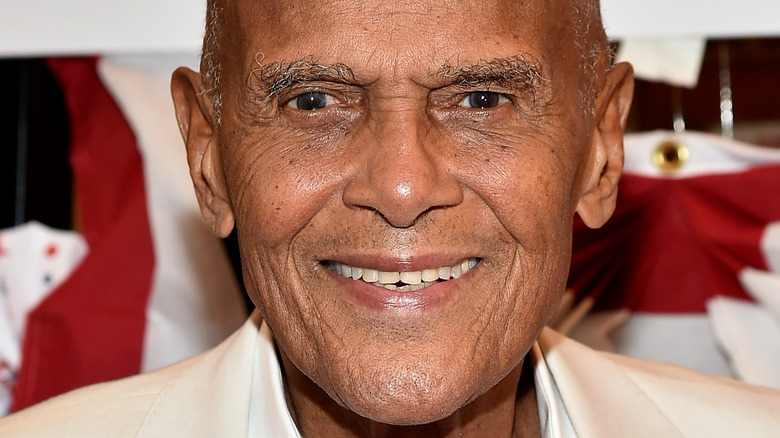

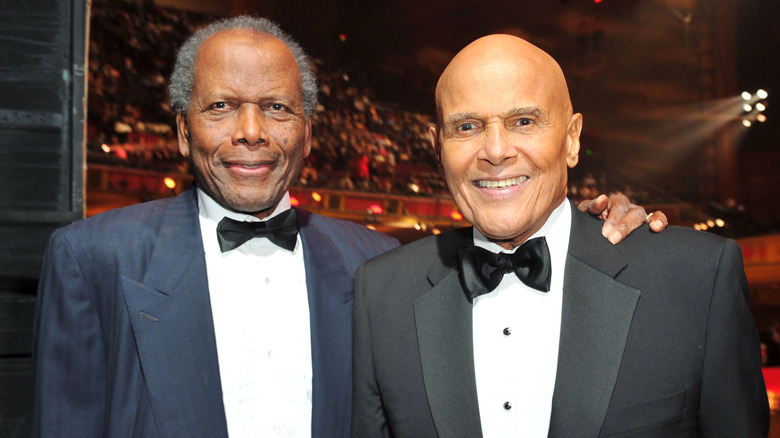

Inside Harry Belafonte's Relationship With Sidney Poitier

Legendary performers and civil rights activists Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier met as young men in New York in the late 1940s who were pursuing their dreams of acting, remaining close friends throughout the years right up until Poitier's death in January 2022 at the age of 94. In fact, according to a 2017 op-ed written by Charles M. Blow for The New York Times, Belafonte considered Poitier to be his first real friend, noting that in his younger days, he "did not get rooted long enough to develop what many people have the joy of experiencing, and that is childhood friends."

The two were 20 years old when they both started working for The American Negro Theatre while also taking classes there, Poitier as a janitor and Belafonte as a stagehand. They shared a common background, as both men were born to West Indian parents, giving them both what Blow called a "quasi-Pan-African sensibility" to their experiences as talented Black American men pursuing entertainment careers in an industry particularly known for its gate-keeping, insularity, and racism. As reported by People, Harry Belafonte made his acting debut at the American Negro Theatre but was unable to perform one night due to illness. His understudy? None other than Sidney Poitier. Per History, Poitier would go on to be the first prominent Black movie star and the first Black man to win an Oscar in 1964 for his role in "Lilies Of The Field."

Belafonte and Poitier risked their lives together

Harry Belafonte set his own barrier-breaking records; his 1956 album "Calypso" introduced the United States to the traditional Caribbean musical genre and was the first full-length album to sell over a million copies, per Biography. He was also the first Black performer to win an Emmy award, which he did in 1959 for "Revlon Revue: Tonight with Belafonte."

In August 1964, Belafonte and Poitier made a daring and heroic trip to Greenwood, Mississippi, as recounted by Andrew Cohen for the Ottawa Citizen. That historic summer, known as Freedom Summer, saw a bevy of Northern college students traveling to the Southern United States in order to register Black citizens to vote. Jim Forman contacted Belafonte to ask for help, and Belafonte quickly raised $70,000 in funds (the modern equivalent of $600,000) and decided to hand-deliver it himself. According to Ottawa Citizen, he asked Poitier to accompany him on the mission, reportedly telling his friend that it would "be harder for them to knock off two Black stars than one. Strength in numbers, man." When they landed in Mississippi, a car chase ensued, with members of the KKK attempting to goad them into speeding. The was an attempt to force the driver into a speed trap, leading to the passengers getting arrested, freed, and turned over to the KKK, which had happened in the past to civil rights activists.

The two legends were closer than brothers

As reported by the Ottawa Citizen, the driver transporting Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, and the $70,000 radioed for help and a convoy appeared, forcing the Klan back. The group arrived at a hall in Greenwood, where they were greeted by a cheering crowd. Poitier reportedly spoke to the people gathered in the hall, saying, "I have been a lonely man all my life ... because I have not found love ... but this room is overflowing with it."

Per the Los Angeles Times, the friends had a temporary falling out right after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., as they disagreed over whether King's funeral should also include a protest march. (Belafonte was of the opinion it should, while Poitier disagreed.) They made up in the early 1970s when Belafonte brought Poitier a film script, which ended up being Poitier's directorial debut, the Western "Buck and the Preacher," with both men producing it and starring in the title roles. They went on to make another movie together, 1974's "Uptown Saturday Night." When Poitier died in 2021, Belafonte said of his friend (via People), "For over 80 years, Sidney and I laughed, cried and made as much mischief as we could. He was truly my brother and partner in trying to make this world a little better. He certainly made mine a whole lot better." Belafonte's daughter Shari told People magazine, "Losing Sidney is probably the most difficult thing my father has had to fathom, more so than losing Martin L. King. They were closer than brothers."