Why Juneteenth Lost Popularity During The Era Of Jim Crow

In 1862 President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, ending slavery all across the U.S. In an age before mass media and modern communication technology, word that slavery had ended failed to reach Galveston, Texas until some three years later, on June 19, 1865. It was then that Major General Gordon Granger announced that all slaves were free by presidential proclamation. With renewed interest in highlighting Black contribution to American history, June 19, now known as Juneteenth, became a federal holiday in 2021, according to Khan Academy.

Some Black communities, though, celebrated Juneteenth for more than a century prior to that. The date first became a holiday in the state of Texas in 1980, as Vox explains. That's while freedmen in Galveston, Texas were celebrating Juneteenth as far as back as 1866, or just one year after they learned of slavery's abolishment, per the Texas State Library and Archives Commission. Although important issues pertaining to race persist in America and elsewhere in the world, all this combined goes to show how far Juneteenth has come since the holiday's popularity, official or otherwise, declined somewhat during the era of Jim Crow.

Jim Crow law in America

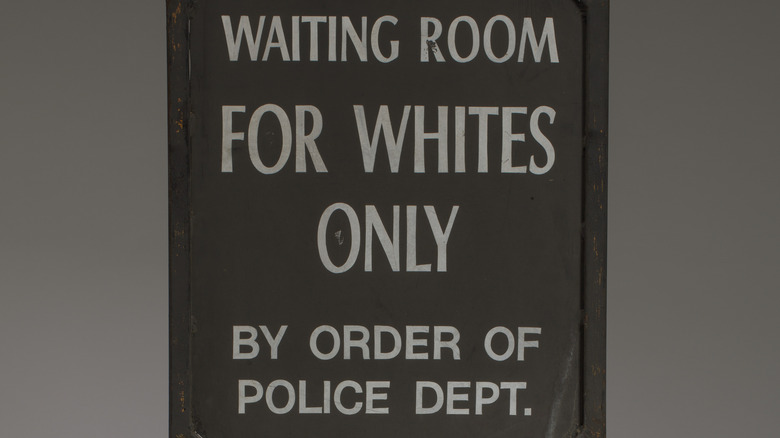

Although slavery officially ended in 1862, the so-called Reconstruction period, which encouraged Black participation in representative government, among other objectives, lasted only until 1877, as Britannica notes. It was then that Jim Crow laws took effect — "Jim Crow" being a colloquial and highly racist term for African Americans taken from minstrelsy. Through what is now known as Jim Crow law, the American South became segregated. From around the late 1870 through the first decades of the 20th century, the Jim Crow laws further disenfranchised Black Americans from society and the political process, sparking the Black civil rights movement that would last through the `50s and `60s.

This sad fact coincided with a dip in Juneteenth's popularity, and not just among white populations in the Northern states, to whom the date began to lose relevance, but also among Black populations in the American South and all over the country. Still, in 1938, roughly 200,000 individuals attended an emancipation celebration near Dallas, Texas. And, as economic pressures spurred by the Great Depression drove Black Americans from their farming lifestyle in the South to the factories of the north and elsewhere — known as the Great Migration – Juneteenth celebrations began to spread to places like Seattle, Washington, and Los Angeles, in the 2010 book "The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration," by Isabel Wilkerson.

Some saw Juneteenth as unpatriotic

Despite the fact that Juneteenth celebrations never completely went away, their popularity did ebb and flow among both white and Black populations all through the late 19th and into the mid-20th century. Among white Americans, Juneteenth, Emancipation, or Jubilee Day remembrances were seen in this period as a reminder of a dark and painful time in American history. Because of this, the popularity of Juneteenth celebrations in general declined around World War I, and this slump continued until the 1940s, as authors Shennette Garrett-Scott, Rebecca Cummings Richardson and Venita Dillard-Allen record in their article "When Peace Come: Teaching the Significance of Juneteenth."

Juneteenth's decline in popularity in the so-called Jim Crow era was not just among white populations, either. The Black community's desire was to engage in the rapid economic and industrial opportunities offered elsewhere in the country, where Juneteenth celebrations were less established, saw the tradition fade among African Americans, according to Rediscovering Black History. However, beginning in the civil rights era around 1950, Juneteenth regained some popularity. Now, with the official designation of a federal holiday, Juneteenth celebrations are increasingly common all across the U.S., according to Vox.