The Copacabana Club Fight That Changed Baseball History

The New York Yankees have often tried to maintain a squeaky clean image for their players and the franchise as a whole. As it currently stands, the organization continues to enforce an edict that came down from late owner George Steinbrenner during the 1973 season that forbids long hair grown below the collar, and facial hair in any form other than a mustache (although facial hair grown in accordance with religious beliefs are permitted), per Mel.

Don Mattingly once found himself on the bench for a game from a dispute over the length of his hair. This was later lampooned in an episode of "The Simpsons" titled "Homer At The Bat" in which Mattingly guest-starred alongside other Major Leaguers, though coincidentally the episode — including the famous scenes about Mattingly's sideburns — was written before his real-life follicle drama (via ESPN).

Rules like the Steinbrenner facial hair policy may seem excessive. Still, it could've been another attempt to rebuild the team's image after it took a massive hit in the late 1950s when several players were involved in a fight at one of the most well-known nightclubs in American history: the Copacabana (via The New York Times).

The early years of the Copacabana

The Copacabana opened in early 1941, according to the New York Post, and its original location was at 10 E. 60th Street in Manhattan. Of course, it doesn't take a history buff to know that 1941 is a pretty significant year in United States history, meaning that the club's heyday was still a few more years down the line. World War II wrapped up in 1945 and in the years that followed, Americans were looking to blow off some steam. Thanks to a 1947 film, the Copacabana became the spot in town where everyone went to do just that, as well as to see and to be seen.

Per IMDb, the film — appropriately titled "Copacabana" — starred comedy legend Groucho Marx and musical star Carmen Miranda. It popularized the club and by 1947, the Copacabana was being headlined by top-tier performers like the comedy team Lewis & Martin, comprised of Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin. In 1957, another Rat Pack member was on stage during one of the most infamous moments in the club's history.

One night in May

By the late 1950s, the Copacabana was known around the globe as one of the most popular celebrity hangouts, and on any night — even a Wednesday night, like May 15, 1957 — a visitor could be treated to a cavalcade of some of the biggest stars, not just from show business, but also from the sports world.

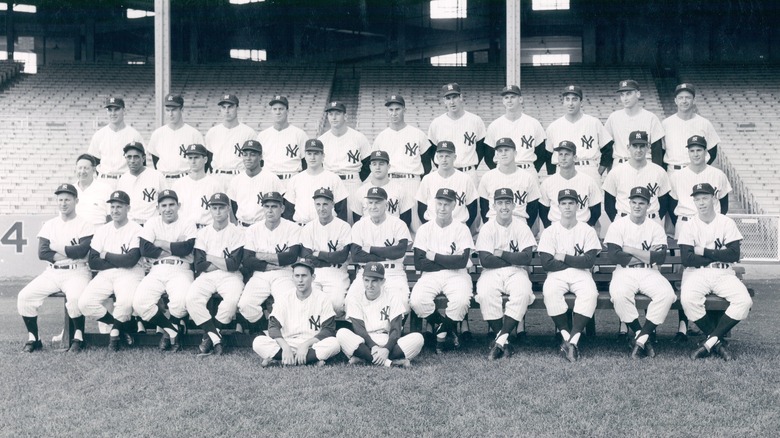

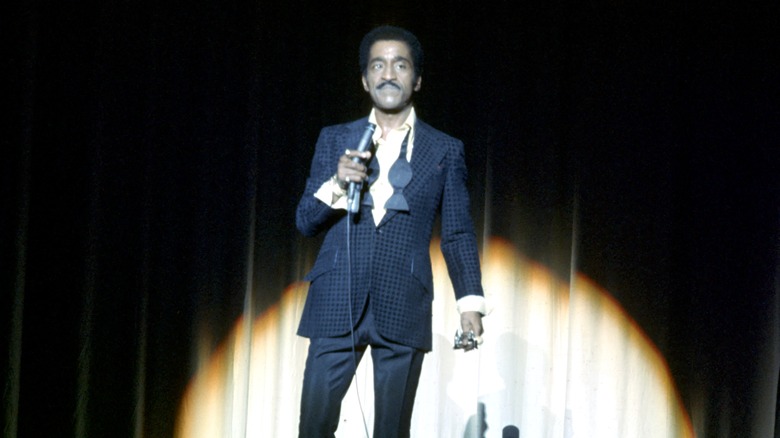

According to The New York Times, a group of about six New York Yankees including Yogi Berra, Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, and Hank Bauer, sauntered into the famous club to celebrate their teammate Billy Martin's birthday. That night, one of the club's usual doormen, 24-year-old Joey Silvestri, was at the club, only he wasn't on the job. He had snuck into the club against the manager's wishes to see Sammy Davis Jr. wrap up his run of shows at the venue. Silvestri was well known by club regulars, but he tried to blend in with the crowd and took a seat at a table with singer Harry Belafonte and (eventual Oscar-winning) actor Sidney Poitier. (This place was loaded with stars on a nightly basis).

A seating snafu

By the time the Yankees arrived at the Copacabana, they had already been at two other stops, so they were already at least somewhat inebriated upon taking their seats at the Copacabana. Had Silvestri been working the door that evening he would've immediately seen the potential problems when a bowling team from Washington Heights entered the club.

According to The New York Times, the club's usual protocol would be to send a group like the bowling team packing, as the club had to maintain its air of classiness; one way to do that was to turn away any potential troublemakers. The bowlers — including a deli owner in his early 40s named Edwin Jones — were allowed into the club by that evening's bouncer, Pauly Pappas. Unfortunately, Pappas failed to usher them toward the cheap seats, referred to as "Burma Road," far from the stage. Not only did the bowlers get a table close to the stage, but they were also just a few feet away from the sauced-up ballplayers.

Fists fly at the Copa

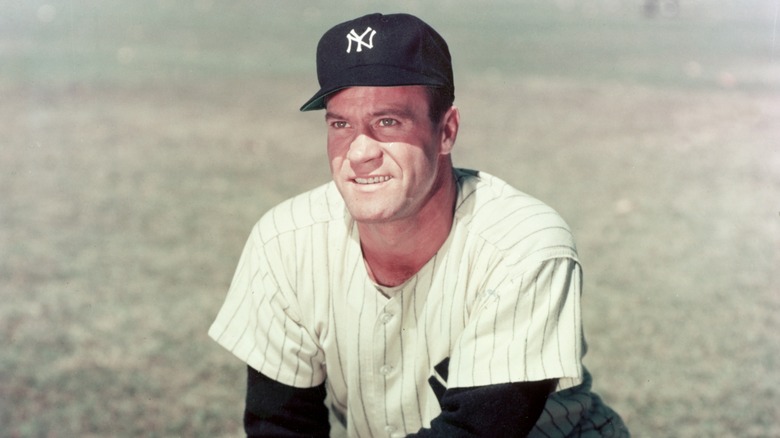

Sammy Davis Jr. took the stage to close out his stint at the club. Not long after a fight broke out in the audience between the Yankees and the nearby bowling team, with Yankees outfielder Hank Bauer (above) accused of delivering a knockout blow to Edwin Jones' jaw that dropped him to the floor. Given that the fight occurred at one of New York City's biggest nightlife hotspots, what transpired quickly became newspaper and tabloid fodder.

Not helping the situation was that before this fiasco, Billy Martin was known for his quick temper, so the idea of a fight breaking out on a night celebrating his birthday didn't shock most people. The repercussions were swift, with several Yankees involved being benched for the next game by manager Casey Stengel.

"I won't pitch Ford because the whole world knows he was out until 2 in the morning," Stengel said, per the New York Daily News. "He knew days in advance that he was supposed to pitch this game. He had no right to be out after hours. If I pitched him and he was hit hard, people would wonder what I was doing." Bauer was moved down the batting order and Berra was given a spot on the bench, but Mickey Mantle was left in the lineup. Stengel gave his reasoning for not punishing Mantle: "I'm not mad enough to take a chance on losing a ball game and possibly the pennant."

The fallout

For some of those involved in the fight, the consequences were worse than being out of the lineup for a day. The Yankees general manager saw the fight and the scandal that surrounded it as a perfect reason to get Billy Martin (above) off the team. According to The New York Times, he feared that Martin's hot-headed ways would influence the centerpiece of his roster in Mickey Mantle. Martin went off to play for other teams — including stops with the Kansas City Athletics, Detroit Tigers, Cleveland Indians, Cincinnati Reds, and Milwaukee Braves, per Baseball Reference — but famously returned to the Bronx for five stints as the Yankees manager.

Meanwhile, Edwin Jones — who had been taken by ambulance to the hospital after the fight — decided to file a lawsuit against both the Copacabana and the Yankees, asking for $250,000 in damages (via the New York Daily News). Jones was a Yankees fan, though after the incident was probably less of an ardent pinstripe supporter. He lost the lawsuit, though he likely never had a chance; as soon as the court proceedings were through, members of the grand jury were hitting up the several Yankees called to testify for autographs.

The truth comes out decades later

Years after most of the people involved in the altercation were dead, Joey Silvestri came forward to The New York Times to offer his explanation as to what really happened. His version of the events paints the Yankees in a vastly different light. Silvestri claimed that Jones and his bowling teammates were heckling Sammy Davis Jr. and using racial epithets and that the Yankees stepped in to defend the performer. However, he also alleged that it wasn't Bauer who leveled Edwin Jones; it was Silvestri himself.

He said that he saw Jones preparing to sucker punch Pauly Pappas, who had stepped in to try to cool things down, and that's when Silvestri sprang into action. He quickly slipped out of sight after the fight but was still interviewed by the police, only he told them that he didn't work on Wednesdays, a line he also told the club's management. Police didn't look too closely into the fight, as in those days the police were paid to look the other way from what went down inside the Copacabana.

The Copacabana went on to become a cultural touchstone and was the subject of Barry Manilow's song "Copacabana (At the Copa)" and appeared in numerous films. The club changed locations over the years and closed from time to time (via Eater New York) but reopened last February at a new location in Hell's Kitchen (per the New York Post).