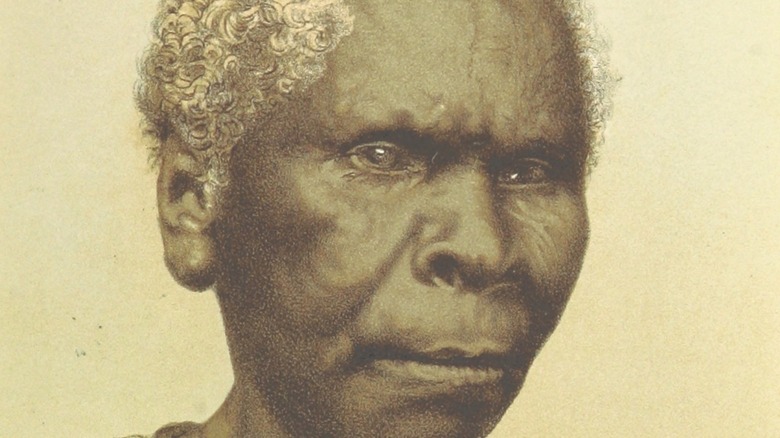

The Tragic True Story Of Truganini: The Last Tasmanian Aboriginal

The fact that Truganini is often referred to as the last Aboriginal Tasmanian is demonstrative of when the Australian government considered their colonial project to be nearing completion. White Europeans had been incorrectly proclaiming the extinction of Tasmania's Aboriginal population for years, even before the death of Truganini. And ever since her death in 1876, Truganini has been referred to as the last Aboriginal Tasmanian, or the last full-blooded Aboriginal Tasmanian but this description is also less than accurate.

While Truganini may have been the last surviving Aboriginal Tasmanian to have lived some of her life among Aboriginal culture and spoken the Tasmanian language, not only does the notion of the last Tasmanian ignore all of the Aboriginal Tasmanian people today, the idea of a "full-blooded" comes from the European and American notions of blood quantum. By labeling her as the last Aboriginal Tasmanian, all those who continued to survive with Aboriginal Tasmanian ancestry were silenced and delegitimized and many Aboriginal Tasmanians today say that "to suggest they are any less Aboriginal since Truganini's passing is insulting to their people's heritage and cultural identity," per The Examiner.

One thing that's clear though is that during her life, Truganini watched her world completely and utterly transform. This is the tragic true story of Truganini: the last Tasmanian Aboriginal.

Early life of Truganini

Truganini, also known as Trugernanner, Trukanini, and Trucanini, was born around 1812 on Lunawanna-alonnah, also known as Bruny Island, near the southern tip of Tasmania. She and her family were Palawa, or Tasmanian Aboriginal people, and although little information remains regarding Truganini's early life, Indigenous Australia writes that her father, Mangerner, was the leader of the Recherche Bay people. During her adolescence, Truganini also reportedly made some visits to Port Davey.

But as the Tasmanian Times notes, Truganini's childhood was marked by the start of British colonialism in Tasmania in 1803. By the end of Truganini's teenage years, her world had become rapidly different from the one her parents and grandparents grew up in. With the onset of white colonialism and an increase in the white population, many Aboriginal people were pushed back from the shores and forced deeper into the bush. Facing raids and abductions by white settlers, whalers, and sealers, attacks were also launched against the invaders.

According to "Black Women and International Law," edited by Jeremy I. Levitt, there was even a bounty placed on the capture of adult Aboriginal people, and sometimes even on children as well, resulting in further violence and attacks against Palawa.

The Black War

From 1824 to 1832, Palawa in Tasmania fought against British colonialists in what is known as Tasmania's Black War. According to The Conversation, the Black War was the most intense frontier conflict in the history of Australia. It's estimated that during Tasmania's Black War, over 800 Palawa were killed, compared to roughly 200 colonists. However, some consider the Black Wars to have started from the early days of British colonization. In Notes on the Tasmanian "Black War," J.C.H. Gill writes that the beginning of the Black War was in 1804, after an officer shot and killed several Palawa and injured several others without provocation.

The hallmark of the Black War was the human chain formed in 1830, known as the Black Line. According to the "Historical Dictionary of Australian Aborigines" by Mitchell Rolls and Murray Johnson, over the course of six weeks, beginning on October 7, 1830, over 2,200 white settlers created a human chain and walked across the Tasmanian country in an attempt to push all the Palawa into the Tasman and Forestier Peninsulas. However, this strategy was ultimately a failure.

The Black War was slowly brought to an end when George Augustus Robinson, a Christian missionary, was able to negotiate several surrenders, along with the agreement that Tasmanian Aborigines would leave their land and move to Wybalenna on Flinders Island, where "the Crown would provide food, clothing, and shelter."

Death of her family

By the time Truganini was 20 years old, she'd lost most of her family as a result of encounters with white settlers. Indigenous Australia writes that Truganini's mother was murdered by sailors, her uncle was killed by soldiers, and her sister was abducted by whalers/sealers and subsequently died. According to "Van Diemen's Land" by Murray David Johnson and Ian McFarlane, Truganini may have had two sisters who were abducted and the sealer/whaler is identified as John Baker. Even her future husband, Paraweena, was murdered by white men seeking timber.

But despite these hardships, as historian and writer Cassandra Pybus notes, Truganini "learnt at a very early age how to negotiate this shockingly apocalyptic world that she is growing up in," per The Sydney Morning Herald. In 1829, she married Woorraddy, who was also from Bruny Island, the same year that she met George Augustus Robinson while he was an administrator of an aboriginal settlement on Bruny Island.

Meeting Robinson

George Augustus Robinson began his resettlement program in 1830, known as the Friendly Mission, and with the help of Truganini and Woorraddy, soon the three began traveling the country. "They acted as guides and as instructors in their languages and customs, which were recorded by Robinson in his journal, the best ethnographic record now available of traditional Tasmanian Aboriginal society."

Truganini and Woorraddy traveled with Robinson and with 14 other Palawa, including Pyterruner, Planobeena, Tunnerminnerwait, and Maulboyhenner, across Tasmania for six years. During their travels, they encountered numerous tribes and tried to convince them all to peacefully resettle on Flinders Island. The Friendly Mission began on January 27, 1830, and by 1834, almost all Palawa had been resettled at Wybalenna on Flinders Island. The Tasmanian Times writes that by this point, the number of Aboriginal Tasmanians numbered in the low hundreds. Without Truganini, Woorraddy, and the other Aboriginals, the Friendly Mission would've been a failure. But with their knowledge of the land, the people, and their diplomacy, Robinson was able to convince many to agree to resettlement.

Truganini's motivation

Although some historians have written that the Palawa who participated in the mission were fooled and manipulated by George Augustus Robinson, others see their actions as one of agency, "of a careful balancing of alternatives available to the survivors in the face of the destructive onslaught of the British colonial enterprise." Truganini herself is among the many who have repeatedly been denied this agency by historians. And according to The Koori History Website, Truganini is quoted as having once said "I knew it was no use my people trying to kill all the white people now, there were so many of them always coming in big boats." With this statement, Truganini demonstrates her awareness that the white colonizers had to be dealt with in another manner.

But as "Black Women and International Law" notes, "We may never know the precise reason why Truganini went along with Robinson in his efforts to gather up and resettle the Tasmanians."

Moving to Flinders Island

Truganini and Woorraddy arrived with other Palawa at the Wybalenna settlement at Flinders Island in November 1835. However, by this point, Truganini was already pretty disillusioned with George Augustus Robinson and his mission, according to the Tasmanian Government. The disillusionment was already well-warranted, but the understanding of where exactly Truganini was sending her people changed everything.

According to "Black Women and International Law," "Wybalenna, the settlement, [was] a place of death." Because of the unsanitary conditions that Palawa were forced to live and work in, rampant disease, and the shock of dislocation, almost all of the Palawa who ended up in the resettlement camp ended up dying there. Indigenous Australia also writes that after being resettled on Flinders Island, Palawa were "Christianized and Europeanized" and forced to become farmers. With this, Truganini realized that Palawa were never going to be given the chance to live their traditional lives on Flinders Island.

Around this time Indigenous Australia also writes that Truganini was renamed Lallah Rookh by Robinson.

Leaving Flinders Island

According to Monument Australia, by 1837, only a handful of those resettled on Flinders Island remained alive. And after a few years, those who were still alive were taken to Oyster Bay. And "Black Women and International Law" writes that in 1847, "the last no longer threatening survivors were allowed to return to the mainland island."

Truganini didn't stay on Flinders Island for long. In March 1836, she and Woorraddy reportedly traveled to the northwest of Tasmania to look for her one remaining family member. When they returned in July 1837 and witnessed the escalating death and decay of the resettlement camp, Truganini reportedly said to her husband that "all the Aborigines would be dead before the houses being constructed for them were completed," according to Indigenous Australia.

Realizing the extent of George Augustus Robinson's broken promises, Truganini subsequently banded together with several other Palawa and together they started to push back against Robinson and the colonial policies. However, the exact story of how and when she became an outlaw is still up for debate.

Becoming an outlaw

There are varied accounts as to when and where Truganini turned against George Augustus Robinson. The Australian Women's Register writes that Truganini accompanied Robinson to Port Phillip, Australia in 1839 and there she learned of additional resettlement communities for mainland Aboriginal people. In light of her experience on Flinders Island, this was reportedly her motivation for turning against Robinson and joining with other Aboriginal people in their resistance.

Other accounts place her leaving Robinson earlier and heading towards the Western Port in Australia with other Palawa. According to Rejected Princesses, at least one historian believes that Truganini was looking for the whalers who'd abducted her sister, but it's unclear whether or not this is true or whether or not Truganini was successful in her search.

During this period, the group, which included Truganini and Woorraddy, reportedly killed several sailors. Subsequently, they were captured and tried for the murders in the colony of Victoria.

The murder trial

Under the law, Aboriginal people weren't allowed to give evidence or testify. And as a result, Warwick Sprawson writes in "The Overland Track" that George Augustus Robinson reportedly happened to show up to the trial to offer his testimony. He reportedly knowingly perjured himself and claimed that Truganini and the other women weren't responsible for their actions because they were being used as pawns by the men.

Out of the group, Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenneer were found guilty and publicly executed on January 20, 1842, To Melbourne records. Although different sources state different names for the two people sentenced to death, including variations like Bob and Jack, there's no argument that at least two Aboriginal people who were in the group with Truganini were executed on January 20. This was also the first instance of capital punishment in Port Phillip.

Meanwhile, Truganini and the other women were sent back to Flinders Island. It's unclear if Woorraddy was part of the group of men or if he was sent back with the women. Indigenous Australia writes that Woorraddy was sent back with the women, but died en route, but Rejected Princesses states that Robinson's memoirs name Woorraddy as one of the men who was hanged in Australia.

Return to Oyster Cove

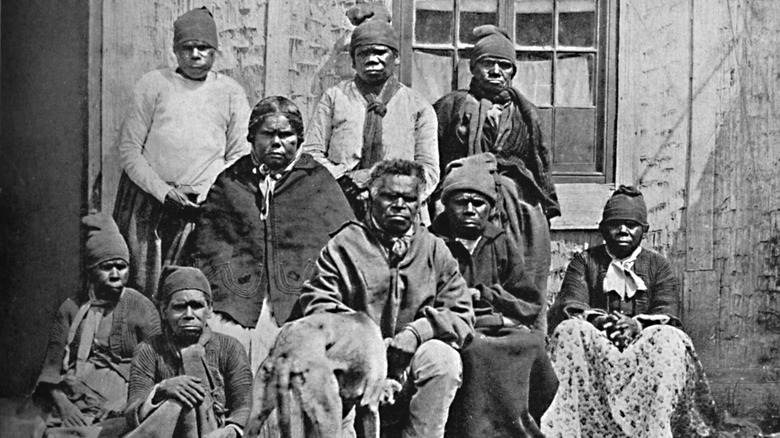

After being captured and exiled back to Tasmania, Truganini joined some of the other Palawa people who were left at Oyster Cove in 1847. The Examiner writes that by this point, there were 45 other Palawa at Oyster Cove. There, they reportedly resumed as much of a traditional lifestyle as they could, which included diving for shellfish and hunting in the bush.

But even in Oyster Cove, the death toll for Aboriginal people kept rising. By 1851, 13 of the 46 people who had arrived there were dead, according to The Companion to Tasmanian History. Eight years later, only 12 Palawa were left. And by 1869, Truganini and William Lanne were the only Palawa left in the area.

By 1874, Truganini was the only remaining survivor of the Oyster Cove group and she was again moved to Hobart town, according to Indigenous Australia, to live with the Dandridge family, who were reportedly her "guardians." However, she reportedly "removed herself spiritually from the Europeans through this phase of her life." Even when George Augustus Robinson came to visit her in Oyster Cove in 1851, Truganini didn't even acknowledge his presence, per The Koori History Website.

What happened to Truganini?

Truganini lived out the rest of her life with Mrs. Dandridge, wife of the former superintendent. Indigenous Australia writes that she died in Mrs. Dandridge's house on May 8, 1876. The Arctic Circle also writes that according to oral histories, Truganini had a child at one point named Louisa Esmai with John Shugnow, though the child ended up being raised in the Kulin Nation.

Before her death, Truganini expressed numerous concerns that white people were going to disturb her dead body, especially after seeing the mutilation of Lanne's body. According to The Last Man by Stefan Petrow, Lanne's dead body was "mutilated by scientists [Dr. William Lodewyk Crowther, Dr. George Strokell, and colleagues] competing for the right to secure the skeleton." And even after the burial, Lanne's body was grave robbed by Strokell. Lanne's skull and his remaining skeleton wouldn't be reunited again until 2011, ABC reports.

Truganini even reportedly said to Reverend H. D. Atkinson, "I know that when I die the Museum wants my body," per Indigenous Australia.

Skeleton on display

Although Truganini pleaded with colonial authorities for a respectful burial and for her ashes to be scattered in the D'Entrecasteaux Channel, her wishes were never honored and her skeleton was grave robbed less than two years after her death by the Royal Society of Tasmania.

Indigenous Australia writes that the Australian government gave permission for the Royal Society of Tasmania to exhume the body provided that it wasn't put on public display and was instead "decently deposited in a secure resting place accessible by special permission to scientific men for scientific purposes." And even these stipulations were ignored and Truganini's skeleton was subsequently put on public display in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery from 1904 to 1947, with the Tasmanian Times stating it was displayed as late as 1951.

The Arctic Circle writes that Truganini's final wishes wouldn't be honored until April 1976, 100 years after her death, when her remains were cremated and scattered in the D'Entrecasteaux Channel.

Aboriginal Tasmanian people today

Despite the dwindling Aboriginal population numbers at the turn of the 20th century, things look a bit different over a century later. According to the BBC, over 23,000 Tasmanians identified as Aboriginal during the 2016 census, "representing 4.6% of the population – higher than the national rate, where 3.3% of Australians identified as Aboriginal." ABC reports that this increase in numbers may have to do with the fact that the Tasmanian Government relaxed the criteria for claiming Aboriginality in 2016. Before the policy change, people were expected to prove their Aboriginal heritage through "a three-part test which included documentary evidence of ancestry. Now people only require self-identification and communal recognition."

Our Tasmania writes that although the complete Aboriginal Tasmanian languages have all been lost, some Tasmanian words remain in use with Palawa people in the Furneaux Islands. In addition, there are also current attempts to reconstruct a language from the available words. Many places have also recognized dual names in English and palawa kani. As of 2021, there are 28 place names with official duel names in Tasmania.

In 2021, the Tasmanian government also announced that they were going to start the process of developing a treaty with the Aboriginal Tasmanian community. There have already been 50 meetings held with Aboriginal communities across Tasmania and many of the meetings heard recurring themes including "compensation, representation in Parliament, sharing of resources and land hand-backs," according to ABC.