Chilling Details About Australia's Last Officially Sanctioned Massacre

For almost 150 years, violence in Australia against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was entirely sanctioned by the state (via the Australian Museum). Police officers would even eagerly join forces with civilians to enact vigilante violence, resulting in hundreds of massacres and the deaths of thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The last of these massacres, known as the Coniston massacre, occurred in the 1920s, after which point it became relatively more difficult for civilians to murder Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with impunity. This power was limited to the police force by the second half of the 20th century.

But the horror of the state-sanctioned massacres isn't easily forgotten by many. Still, it took until 2018 — 90 years since the Coniston massacre — for the Northern Territory Police commissioner to issue an apology on behalf of the officers who participated in the last state-sanctioned massacre of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

During the 90th anniversary memorial for those killed in the Coniston massacre, Central Land Council chairman Francis Jupurrurla Kelly stated that "until all Australians know about the crimes committed against our families and many others during hundreds of documented colonial massacres we can't move forward as one mob, one country" (via the National Indigenous Times). Here are some chilling details about Australia's last officially sanctioned massacre.

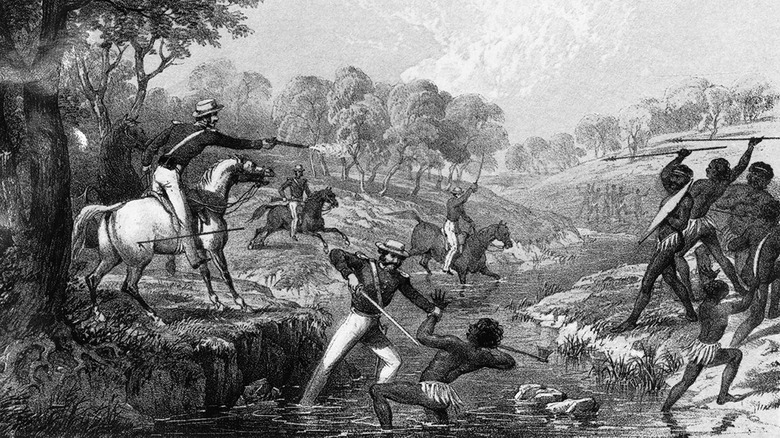

The Australian Frontier Wars

The colonial invasion and warfare aimed at taking over the continent of Australia is typically referred to as the Australian Frontier Wars. Lasting from 1788 into the 1930s, the Frontier Wars resulted in the deaths of no less than 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, according to The Guardian. In comparison, it's estimated that between 2,000 and 5,000 Europeans were killed.

Common Ground writes that there were several well-known massacres that were committed by white people during the Frontier Wars, including the Waterloo Creek massacre. But the most famous of the massacres is the Myall creek massacre, which is noteworthy for the fact that seven out of the 12 perpetrators of the massacre were charged and hanged for their participation in the massacre. "It is a significant moment in history because it was the only time white people were found guilty or held accountable for their violence towards First Nations people during the Frontier Wars." The Killing Times reports that government forces actively participated in the massacres into the late 1920s.

According to the National Indigenous Times, Central Land Council chairman Francis Jupurrurla Kelly has stated that many Australians have failed to understand the crimes that were committed against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

A four-year drought

In the years preceding the Coniston massacre, the region known as the Northern Territory of Australia experienced a severe drought that started in 1924. According to Aboriginal History, this drought was the worst drought ever recorded in Central Australia. By 1928, the severe drought led the traditional water sources of the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye nations to dry up. In addition, overgrazing contributed to the decimation of vegetation. And Australian Frontier Conflicts writes that because most of the permanent waterholes and soaks were on colonized lands, the Aboriginal peoples were forced to confront white Australians more and more for water and food.

After the massacre at Coniston was made known to the public, the Commonwealth Government "sought to establish that [the] drought was either non-existent or negligible in its impact — certainly in no way responsible for Aboriginal violence."

In response to the food shortages, the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye often speared the cattle of pastoralists. Common Ground also writes that many waterholes used by Aboriginal people were frequently destroyed by the pastoralists' cattle. And while killing cattle was an offense punishable by death, the punishment for killing an Aboriginal person was "non-existent," according to ON LINE opinion.

The murder of Fred Brooks

Dingo trapper Frederick Brooks set out for dingo scalping on August 2, 1928, accompanied by two Aboriginal assistants, Skipper and Dodger. Lexology writes that Brooks was in his 60s at the time, but little more is known about his background.

According to "The Great War," Brooks had received permission to go trapping on the land by his friend Randal Stafford and ended up setting-up camp a water source about 14 miles away from Coniston station, also known as a soakage, at Yurrkuru. And while trapping, Brooks reportedly encountered a Warlpiri man named Kamalyarrpa Japanangka, also known as Bullfrog, with whom he made an arrangement to get his clothes washed by Marungardi, Japanangka's wife, in exchange for food and tobacco.

Five days after Brooks set out, his body was found in the morning by Skipper and Dodger on August 7, 1928, "speared and buried in a rabbit warren at a water hole [14 miles] west of the Coniston Station homestead," writes Gordon Briscoe in "Racial Folly."

Why was Brooks murdered?

Although Brooks' murder by Warlpiri people is largely accepted as fact, the reason behind his murder remains up for speculation up to a century after his death. Before setting out for dingo scalping, Brooks was reportedly told by his friend Stafford that he shouldn't venture more than 14 miles west of Coniston station because there had already been threats made towards Stafford and Alice, the Warlpiri woman he lived with, from the Warlpiri people (via Aboriginal History).

Another account states that Brooks never honored his agreement with Japanangka. According to "Racial Folly," Brooks reportedly refused to allow Marungardi to return and tried to keep her at the station. And when she finally managed to return, she returned with neither the tobacco nor the food that Brooks owed her. Common Ground notes that some secondary accounts also claim that Brooks may have sexually assulted one or two of Japanangka's wives. In 1975, Japanangka's granddaughter stated that "At Yurrkuru my grandfather killed a whitefella. He hit the whitefella because the whitefella stole his wife." Our Song Lines writes that breaking Aborginial marriage law was considered a crime punishable by death.

Other accounts, mainly from European sources, claim that Brooks was killed "so as to get possession of his flour and tobacco."

Murray's lynch mob

After news spread of Brooks' death, Mounted Constable William George Murray ordered on August 12 that any and all Aboriginal people who came into Coniston station should be arrested and questioned. In his police report, Murray would later claim that he determined the names of 20 people who were responsible for Brooks' murder and in response, he and pastoralist William John Morton gathered a lynch mob and of civilians and police officers to hunt for Japanangka. Our Song Lines notes that these 20 people were never identified by name, nor was the source who accused them named in the official police report.

According to SBS News, the lynch mob even used Aboriginal people who were trackers to help search for the perpetrators. And "none of the legislative requirements to swear members of this party in as special constables were complied with, so the nonpolice members were nothing more than vigilantes," writes Aboriginal History.

But Murray's lynch mob was hardly just looking for the culprits of the murder and at the first camp they rode up to, they opened fire indiscriminately. It's believed that Marungardi was one of those killed in the first camp. This also wasn't the first time in the Northern Territory that vigilantes had gone on a murder spree. In 1884, there was a massacre of Aboriginal people after several miners were murdered near the Daly River.

Months of slaughter

Between August 14 and October 18, 1928, Murray's lynch mob rode through Central Australia, slaughtering any and all Aboriginal people they encountered. According to NACCHO, the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye nations were the people largely affected by the massacres. Although the Board of Enquiry reported that the official death toll was 31, it's believed that at least 100 people, if not more, were murdered during the months-long killing-spree. No one was spared during the massacres, not even children. And whenever Aboriginal people tried to defend themselves, Murray would claim that he was simply attacking in self-defense.

Our Song Lines writes that the massacres occurred in dozens of places, including Rabbit Bore, Mt Theo, Tipinpa, Mission Creek, Dingo Waterhole, Boomerang Waterhole, Circle Well, and Baxter's Well. And although Murray and his men sometimes captured prisoners, "almost all of them succumbed to fatal gunshot wounds."

Two Warlpiri men named Akirkra and Padygar survived the killing spree and were taken back to Darwin and tried for Brooks' murder. Although neither men spoke English, they each allegedly made separate confessions. On October 19, Murray wrote a one-page report on the patrol without noting the exact number of Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, and Kaytetye people that were murdered by the lynch mob. Murray reportedly put little effort into his report because "I did it in a very great hurry as I had to go out about some other matters," referring to the upcoming trial of Akirkra and Padygar (per Aboriginal History).

Land dispossession

In addition to further decimating the Aboriginal population of Australia, the Coniston massacres also facilitated the dispossession of Aboriginal land by white settlers. And considering the fact that land and water resources were already being fought over, the mass killings made it possible for white Australians to simply assume control of whatever land was left in the wake of the killing spree. According to Land Rights News: Central Australia, "people got shot at all the water holes – they got shot and those springs were taken over for cattle and Yapa [Warlpiri] were pushed off their country."

Any attempt to retrieve water during the day became an impossibility. One survivor of the massacres recounted that "when I was a little girl I saw my people shot at—all because they lived off this country and because they were Aborigines. Some of our parents and grandparents hid us in caves. During the day we'd go without water and hide from the whitefellas. At night our parents would sneak out to the soakages to get water for us to drink," per the Australian War Memorial.

According to "Dislocating The Frontier," those who managed to survive the massacres ended up fleeing the area and were adopted into local groups, having lost their own ancestral lands in the process.

Acquitting the accused

Because Akirkra and Padygar had pleaded guilty before the Magistrate Allchurch in Alice Springs, many assumed that the trial against them was going to be a formality. As written in "Coniston" by Michael Bradley, "the police and prosecutors had not bothered with such things as forensic evidence or witnesses." The only witness brought to the stand was a young Aboriginal boy named Lala, and it's unclear if Lala was even present at the time of the murder.

One man in the jury composed of all-white men reportedly stated that he could not sit on the jury "as he knew nothing of Aboriginal customs or language, was therefore not a peer of the accused and that to include him would offend Magna Carta." He was excused from jury duty, although the judge claimed that he had no idea what the man was referring to.

Aboriginal History writes that because of inconsistencies in Lala's testimonies as well as the fact that the two confessions of guilt were determined to be inadmissible, both Akirkra and Padygar were ultimately acquitted. The trial also ended up "attracting the attention of the missionary community to the killing of at least 17 Warlpiri."

The Board of Enquiry

After being lobbied by missionaries and humanitarian societies, the Australian government appointed a Board of Enquiry to look into the Coniston massacre. According to Aboriginal History, the Board of Enquiry was compromised from the very beginning. The board was composed of a police magistrate, a police inspector, and Murray's superior Police Commissioner JC Cawood (who was better suited as a witness). The missionaries argued that one of their own should also appear on the Board of Enquiry, and after it was allowed for missionary Ernest Kramer to be part of the inquiry, it was determined that Murray should also be allowed to participate.

The Board of Enquiry was meant to determine whether or not the murders of dozens of Aboriginal people was provoked. After hearing from 30 witnesses over the course of 18 days — and Our Song Lines notes that not a single member of the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye nations was called to testify — the Board made their findings public on January 30, 1929. Land Rights News: Central Australia reports that per the official inquiry, Murray and his men only killed 31 Aboriginal people, all of whom were slain in self-defense (meaning no charges were going to be made against Murray's crew).

"The Board also stated that there was no evidence of any starvation of Aboriginal people in Central Australia" (per Aboriginal History), ignoring all of the evidence of the severe drought and starvation that was affecting the people of the Northern Territory.

Last of the killing times

Between 1794 and 1926, there were at least 270 massacres against Aboriginal people, which were intended by white Europeans to exterminate the Aboriginal people. This part of Australian history is known as "the killing times," used to describe the officially state-sanctioned massacres, and Our Song Lines writes that the Coniston massacre is considered to be the last one. According to "Remembering the Myall Ck Massacre," evidence that the killings were state-sanctioned lies in "the fact that vast numbers of genocidal murders in colonial Australia went unpunished[.]"

The Guardian reports that initially, the massacres were perpetrated by British soldiers, then police, later settlers, with police and settlers often working together. Native police under the colonial government were also involved in the mass killings.

These attacks reportedly became more and more lethal over time. Although the average number of deaths among Aboriginal people increased, "from the early 1900s casualties among the settlers ended entirely – with the exception of one death in 1928." Most often, the massacres were motivated as revenge for the killing of a white settler, but over 50 attacks were in response to the killing or theft of livestock or property.

Violence against Aboriginal people

Although the violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples stopped being state-sanctioned, this didn't mean that the violence subsided. The dispossession of land, forced migration, violence, relocation to missions and reserves, institutionalization, and child removal have all continued as part of the campaign against the Aboriginal peoples of Australia.

Between 1910 and the 1970s, hundreds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies, as well as church missions. Most children were put into institutions, while others were adopted into white families and used for domestic work (via Common Ground). These institutions mirror the boarding schools Indigenous children in North America were sent to, and they were similarly horrific places of abuse and neglect.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are also disproportionately affected by police violence in Australia. The Guardian reports that since 1991, up to 474 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples have died in police and prison custody. In the past 40 years, only two cases of Aboriginal deaths in custody led to murder charges for the police, but neither case resulted in a conviction, according to the Harvard International Review. The imprisonment rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders peoples is also 12 times higher than the imprisonment rate for non-Aboriginal people.