The Oldest Foods In The World Discovered By Archaeologists

In today's 21st century world, it's no secret that the foodie culture is alive and well. One look at any social media site will make it clear just how creative people are getting these days, and here's the thing: That's actually nothing new, and it may be more important to the survival of humans as a species than it seems.

Archaeologists have long been wondering just why Homo sapiens were able to fight and claw their way to the top of the food chain because let's face it — humans are soft and squishy, while other creatures we share the planet with are not. Archaeologists from the University of Oxford have an interesting theory that, in a nutshell, suggests early humans' adventurous eating habits helped encourage them to spread out into new territories (via NPR). It's unclear whether our ancient ancestors were looking for a little variety to their diet or were just able to eat whatever they found in the new places they moved to, but either way, research suggests that our taste for new eats has gone a long way to shaping the history of the species.

So, what were our ancient ancestors eating, and do traces of ancient meals still exist today? Absolutely! Can you sample some of them? Technically, yes ... if you're both very lucky and very brave.

Bog butter

Over tens of thousands of years, some of Ireland's lakes were turned into bogs, says The Living Bog. These highly acidic, nutrient-rich patches of the landscape haven't just supplied the country with fuel for a long time and been home to a diverse ecosystem, either — they're also great for preserving things.

Bog bodies are definitely a thing, sometimes discovered in such an incredible state of preservation that it kicks off a modern-day murder investigation. Also preserved in bogs? Butter, and a lot of it. According to a 1997 report in The Journal of Irish Archaeology (via JSTOR), most bog butter deposits have been found in the western counties, with Co. Mayo leading the way. Age estimates also vary: According to CNN, one 100-pound stash of bog butter discovered in Co. Offaly in 2013 was estimated to be around 5,000 years old. A few years prior to that, a 3,000-year-old, 77-pound lump of butter was found in Co. Kildare (via NBC News).

At the time it was buried, butter was incredibly valuable. Interpretations of what such large stashes of butter were used for vary, with some believing it was used to pay rent, while others think it may have been made as a ritual offering or buried in the bogs as a way of preserving it for later use. Hundreds of samples have been found — usually, they're buried in wooden containers, skins, or in baskets, and they're described as being whitish, cheesy-smelling, and technically still edible.

Ancient noodles from China

Noodles have been a staple food for a long time, and it's still argued whether it's the Arabic world, the Asian, or the Italian that deserves the credit for creating this popular food (via National Geographic). For a long time, the oldest historical mention of noodles was in a Han Dynasty text dating to between A.D. 25 and 220, but a 2005 discovery blew that right out of the water.

Archaeologists were excavating an area of China called the Lajia settlement, which had been occupied for a long time before being destroyed by earthquakes and flooding. One of the treasures they uncovered among the debris was an overturned bowl, still filled with noodles that were perfectly preserved in the space formed by the upside-down bowl and the sediment it became embedded in.

Dr. Houyuan Lu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing described the find (via The Guardian): "Thin, delicate, and yellow, they resembled the traditional La-Mian noodle (like the ones pictured) that is made by repeatedly pulling and stretching the dough by hand." The find is even more impressive when talking dates: It's estimated that it was somewhere around 4,000 years ago that someone's dinner was interrupted and caused them to overturn the bowl that wouldn't be moved for four millennia.

The noodles were, sadly, turned to dust when they were exposed to the air, but archaeologists were able to examine what was left behind and determine they were made from millet.

The oldest bottle of wine

Wine can get ridiculously expensive, and that's no joke: The Drinks Business says that in 2021, a three-year-old, 6-liter bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon sold for a whopping $1 million. Does it taste like grapes? Probably. Bottled by fairies and sealed with a unicorn horn? It better be.

That bottle was only three years old, and that's nowhere near as cool as the Speyer wine bottle. Kept at the Historical Museum of the Palatinate and also called the Romerwein aus Speyer, it's somewhere around 1,700 years old. The bottle was the only still-sealed, still-filled bottle discovered during the 1867 excavation of the tomb of a Roman nobleman, perhaps unsurprisingly near the city of Speyer. According to Atlas Obscura, the tomb was dated to A.D. 325, and since the bottle has never been opened, it's kind of a guess as to what the wine was made from. Based on the era, it's believed to be made with a mix of local grapes and herbs, then sealed with a layer of olive oil that ultimately kept the entire thing fresh.

Now, the most important question: Can you drink it? Surprisingly, yes. The museum staff says that it's so well-preserved that someone could drink it and live to tell the tale, but given that most of their employees don't even handle it for fear of breaking it, it's safe to say that no one's going to be cracking the seal on that bottle anytime soon.

Ancient bone soup

Information on this one is kind of scarce, and that's a shame: It's not every day that archaeologists discover a 2,400-year-old bowl of soup.

According to the BBC, the discovery came when the Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology was excavating a tomb ahead of the construction of an addition to an airport. The site — reportedly not far from where the discovery of the famous terracotta warriors was made — was dated to between 475 and 221 B.C., and while it was unclear just who was buried in the tomb, archaeologists guessed it was someone who had been a part of the military or land-owning classes.

The soup was discovered in a bronze vessel, and although it had turned green from oxidation, archaeologists said it was likely to be a meal of bone and broth. More tests were reportedly going to be done, but further information hasn't been forthcoming. Interestingly, there's still a bit of a footnote to this: John Speth is an archaeologist with the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and told NPR that he's been fascinated with the question of just how long soups and stews have been made. Given that Neanderthals would have needed to be able to boil meat, he suggests that soup-making goes all the way back to them.

Pompeii's street food

Here's a bit of a unique one in that archaeologists know exactly how to date it — to A.D. 79 and the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. That, of course, is when Pompeii was infamously preserved in complete and heartbreaking glory. Excavations have been ongoing, and it wasn't until 2020 that The Guardian reported archaeologists finished excavating something really cool: a Roman-era snack bar.

The street food stall was at the intersection of two streets, and as work progressed, excavations revealed detailed frescos advertising just what had been on the menu. That included things like duck and chickens, and yes, when they excavated the stand, remnants of the last meals cooked for that fateful day were also uncovered. Archaeologists discovered snails, ducks, goats, fish, pigs, and fava beans, left behind and preserved with the rest of the city. Pots of hot food were set into the holes in the counter, and those beans? They weren't served on their own — it's believed they were added to wine.

Based on the state of the stand, representatives from the Archaeologist Park of Pompeii believe that the stand's owners abandoned their post as the eruption started. Massimo Osanna explained: "[I]t is possible that someone, perhaps the oldest man, stayed behind and perished during the first phase of the eruption." The find is a huge one: Officially called a thermopolium, it's one of 80 that were scattered around Pompeii and the first to be fully excavated (via NPR).

Flour

Flour, agriculture, bread ... they're all considered the building blocks of a relatively modern diet, and for a long time, it was believed that our ancient Stone Age ancestors were more the hunting, carnivorous type. A shocking yet deceptively simple discovery changed all that, and it was detailed by a joint study published in 2010 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Archaeologists examined a series of sites, including locations in Italy, the Czech Republic, and Russia. They found not just grinding stones but also flour residue that meant Stone Age humans were actually grinding and using flour about 20,000 years before the rise of widespread agriculture (via Nature). The source of the 30,000-year-old flour was identified as coming from cattails, ferns, and a plant called Brachypodium, a kind of grass. The implications were pretty staggering and showed that Stone Age people were actually gathering wild vegetation to grind into flour and cook. Even cooler? Researchers estimate that they were making food that was similar in nutritional value to today's cereal flakes.

Since then, more evidence of early flour-making has been found. In 2015, NPR reported on a discovery made by a team from the University of Florence. They had been working in a cave in southern Italy called the Grotta Paglicci and discovered a grinding stone and similar flour residue they estimated at 32,000 years old. At the time of the finding, they said it was the oldest processed food ever discovered.

Mummy cheese

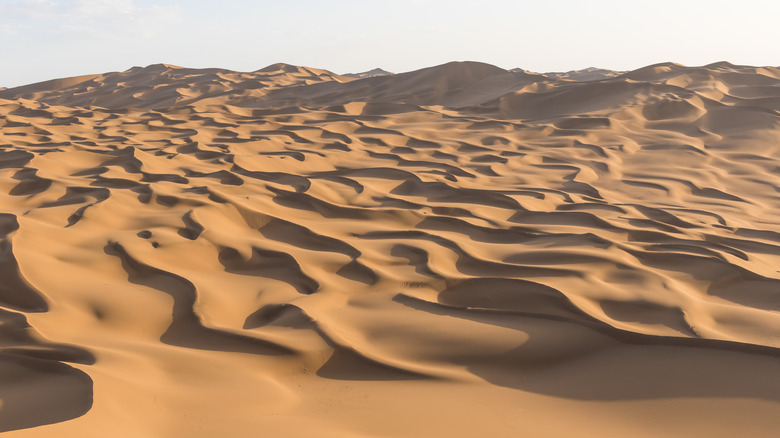

The idea of a mummy might conjure up images of ancient Egypt, but for the discovery of the world's oldest cheese, archaeologists had to head to China and the Taklamakan Desert. That, says USA Today, is where archaeologists in the 1930s first recorded the existence of the burial places of a Bronze Age civilization. Burials were dated to between 1450 and 1650 B.C., when the dead were carefully placed in boat-like coffins that were wrapped with cowhide before being dried and preserved by the hot, dry climate over the following centuries. When they were found, many were still wearing their felt, wool, and leather clothing, and many had strange substances on their chests.

The 3,600-year-old substance was analyzed by experts at Germany's Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics, who confirmed that it was ancient cheese. They were even able to determine the method used for making the cheese and said that it was similar to today's kefir in that it came from yeast and bacteria instead of animal-based rennet. Archaeologists say that it's not clear just what the reasoning behind the cheese was, with some guessing being that it was included as food to be eaten in the afterlife or as a type of tribute. It's just one more mystery the mummies hold: NBC News says there isn't much that's known about them and adds that they're from a non-Asian culture that appeared in China during the Bronze Age, then vanished.

Ancient Roman garum

It's rare that a fridge doesn't have a few bottles of condiments in it, and that absolutely isn't a new thing: Ancient Romans had their own wildly popular condiment called garum, and it's made by fermenting fish guts in salt (via Vox). Weird? A little bit, but given that it was popular all across the Roman Empire, maybe don't knock it until you try it. And thanks to a discovery made in the waters off the Italian coast, there's some of the original stuff still kicking around.

In 2015, lead archaeologist Dr. Simon Luca Trigona spoke with The Local about what they'd spent the previous two years doing, diving about 5 miles off the coast near Alassio. Resting on the seafloor is a shipwreck dated to the first or second century — in other words, the ship sank about 2,000 years ago. Unusually, the team believes they know exactly what the ship was doing when it sank — probably under the weight of the cargo — and Trigona says it was likely sailing along a well-traveled trade route from Italy to Spain and Portugal. According to ABC News, it's estimated that there were around 200 amphorae of garum on board.

That's not the only ancient Roman shipwreck that's been found still laden with ancient foods. According to The Guardian, Italian authorities announced in 2021 that they had discovered another wreck off Palermo. Dated to the second century B.C., the wreck still contained around 50 amphorae believed to contain wine.

Iron Age olives and seasonings

It's one of those things that always just kind of seemed to make sense — the idea that the Mediterranean diet spread into northern Europe and Britain with the Romans. Logical, right? Only, not quite.

In 2011, an archaeological dig done by the University of Reading demonstrated how even the smallest of finds could rewrite history. They were working on an excavation in the ancient Roman town of Silchester when they found a single olive pit, along with coriander, dill, and celery seeds. The finds were dated to the Late Iron Age — between the years A.D. 40 and 50 — and it had staggering implications.

The fruits and seasonings were all grown in the Mediterranean at that time, and no one had any idea were being imported into Britain along trade routes that would have taken weeks to get from origin to destination. Head archaeologist and professor Michael Fulford explained: "[T]his unique discovery shows just how sophisticated Britain's trade in food and global links were, even before the Romans colonized in the first century A.D."

Ancient Egypt's mummified foods

When it comes to treasure troves of ancient foods, there's perhaps no better place to look than ancient Egyptian tombs, starting with the discovery of Tutankhamun's remains and the grave goods that were left with him.

King Tut died around 1324 B.C. and was largely forgotten until the 1922 discovery and excavation of his tomb and the reveal of the staggering array of precious goods that he was buried with (via History). Among those goods, says McGill's Office for Science and Society, was a jar of honey that was just as fresh as the day it was sealed in the tomb ... nearly 3,300 years prior. How did they know how fresh it was? They tasted it.

That's not the only thing that's been found in ancient tombs, and according to National Geographic, one of the most frequently found — including in the tomb belonging to Tut's great-grandparents, Yuya and Tuyu — are fascinating artifacts called "victual mummies," or "meat mummies." These meat mummies were mummified meats, including duck, birds, and pieces of larger animals like antelope, cattle, and goat. The meat was preserved by drying it and then covering it with a mixture of resins.

While Tut's great-grandparents were buried with 17 of these so-called meat mummies, Tut himself was sealed in his tomb with 48 of them. Live Science says that mummified meats are one of the most common among the items left in Egyptian tombs, with no word on whether or not anyone's tried to eat one.

Ancient bread

In 1999, the BBC reported on the discovery of what was deemed to be the oldest piece of bread ever found in Britain. It was discovered during a dig in Oxfordshire, and after being analyzed on a molecular level, it was found to be around 5,500 years old — meaning it had been baked sometime between 3,620 and 3,350 B.C. That's impressively old, but that's also when ancient bakers in the Middle East told Britain to hold their beer — they've got this.

In 2018, Haaretz reported that a group of archaeologists from universities in London, Cambridge, and Denmark had found a piece of pita in Jordan's Black Desert. The unleavened, cracker-like bread was found to be a whopping 14,400 years old, and yes, that pre-dates large-scale agriculture by quite a bit. That's not to say they weren't growing things: Grain cultivation goes back at least 23,000 years (maybe), and alongside the bread were the remains of other foods, including 95 types of edible plants.

Were they purpose-grown or collected? No one's quite sure — although they're leaning toward the idea that grains, grasses, and plants were collected from the wild — but they were able to tell an impressive amount about the bread. It was a mixture of flour, water, and ergo, and it had been kneaded and baked over an open fire.

Ancient Scottish butter

Scotland, like Ireland, has peat bogs. It's not entirely surprising to learn, then, that ancient bog butter has also been found in Scotland, where these incredibly old stashes of butter have been made for thousands of years (via ZME Science). That's not what this is about, though.

Scotland's Loch Tay was once the home of a civilization of crannog-dwellers, and what's a crannog? According to The Scottish Crannog Centre, they're essentially wooden houses built out over lakes, and they're connected to the shore by — usually — narrow bridges. They were only built to last for a few decades, and once they had served their purpose, they would collapse into the lake, and new ones would be built. In 2020, The Scotsman reported on a pretty surprising item that was discovered during excavations of the remains of around 17 Iron Age crannogs that had collapsed into the lake around 2,500 years ago. The lake had actually acted in a way similar to what archaeologists have seen with the peat bogs and created the perfect environment to preserve a wooden butter dish and some ancient butter.

The butter was a less-than-appetizing grey, but tests still confirmed the presence of dairy and the likelihood it had been made from cow's milk. The dish itself gave a fascinating glimpse into how it was made, and experts believe the last stage of butter-making was done in the dish itself, with the help of a woven cloth used to push out the last of the liquids.

Ancient Peruvian popcorn

Some snacks just seem like they're pretty modern, and popcorn is one of those. It's the stuff of movie theaters and nights in front of Netflix ... and what's more modern than that? Nothing's further from the truth, though, and according to National Geographic, the discovery of a corn cob with popped kernels didn't just prove that ancient Peruvians had great taste in snacks — it also proved they were eating popcorn as far back as 6,700 years ago.

The cobs came from excavations done along the northern coast of Peru, at locations called Huaca Prieta and Paredones. The cobs were exactly the sort of thing that get archaeologists excited as they gave a bit of insight into what ancient people were eating and also pushed back the history of corn by about 2,000 years. Archaeologist Dolores Piperno — from Washington, D.C.'s National Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian — says that researchers have even been able to figure out just how they were making popcorn. Cobs would be wrapped and then either popped in an oven, roasted over hot coals, or held over an open fire. She says that although corn was first domesticated in Mexico around 9,000 years ago and then spread to South American agriculture — which created hundreds of different varieties — the scarcity of popped cobs suggests that as it is today, popcorn was a treat instead of a main course.