Ernest Hemingway's Scathing Comments About F Scott Fitzgerald Shows How Real Their Feud Was

It should have been one of American literature's most enduring friendships, the glorious coming together of two of the 20th century's finest novelists and short story writers in a collaboration that illuminated each other's work and propelled the pair forward towards greater writing.

However, the relationship between Ernest Hemingway (pictured) and his American literary compatriot in 1920s Paris, F. Scott Fitzgerald, was far more complicated. Rather than a mutual creative blossoming, their friendship has been recast in recent decades as a strikingly bitter rivalry, due, mostly, to Hemingway's competitiveness and willingness to paint himself in a positive light at the expense of Fitzgerald.

The two met in a Paris bar in 1925. As the critic Jeffrey Hart notes, Fitzgerald, who was three years Hemingway's senior, was by far the more successful of the two. Not only had he been well-published — and recompensed — for around half a decade, but he'd also built a considerable readership and critical response through the publication of novels and short works in major magazines. Hemingway, by comparison, was keeping his powder dry, happily honing his craft while slowly publishing selected works in small-circulation pamphlets. All that was to change, however, as his new literary friend seemed to ascend to new heights of writing talent. Hemingway felt the need to step into the limelight himself.

Hemingway's response to 'Gatsby'

As Jeffrey Hart has argued in The Sewanee Review, the year of the two writers' meeting was also a crucial time for publishing new volumes that would take their careers to the next level. Hemingway published "In Our Time," his first collection of short stories, the reception of which was buoyed by praise from the literary heavyweight Ford Maddox Ford.

Meanwhile, F. Scott Fitzgerald (pictured) published "The Great Gatsby," which, for many readers counts among the greatest novels of the 20th century. Though it wasn't an immediate success, the novel gained significant attention in Paris literary circles, and its reputation has continued to grow; today, it is named among a handful of others as the definitive Great American Novel.

The aesthetic success of "The Great Gatsby" provoked in Hemingway such jealous feelings that his next project, a novel, was written as a direct riposte to Fitzgerald's critically-acclaimed work (via Hart). Hemingway's "The Sun Also Rises" was published in 1926, and, like "Gatsby," follows the travails of a group of young people and their rivalries and romances. Hart notes that Hemingway's novel seemingly attempts to outdo Fizgerald's masterwork by demonstrating the superiority of Hemingway's sparse modernist style. Hart goes on to say that the novel contains, in the character of Princeton graduate Robert Cohn, a proxy for Fitzgerald, who is characterized as a "romantic and a bad novelist." Hart continues by saying Hemmingway's novel was composed with great rage at Fitzgerald's success and maddened by his own lack of recognition and his minuscule readership by comparison.

A posthumous attack

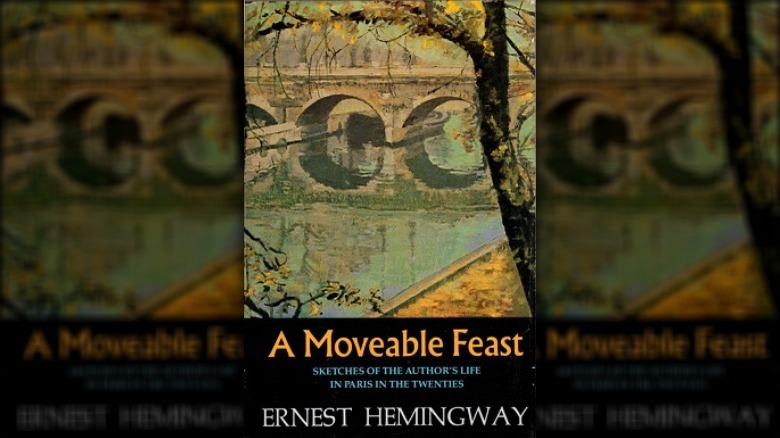

Despite F. Scott Fitzgerald's monumental career upturn in the years following the publication of "The Great Gatsby," the author lived a troubled life, with him and his wife, Zelda, struggling with alcoholism and mental illness, according to Britannica. Fitzgerald died in 1940 at the age of 44. Nevertheless, Hemingway's final word on Fitzgerald was not a friendly one; in fact, he performed what many critics consider to be a character assassination of his literary friend. In 1964, Hemingway's longtime publisher, Scribner's, posthumously published "A Moveable Feast," the author's memoir of his years in Paris which includes three caustic chapters dedicated to his relationship with the creator of "Gatsby."

"A Moveable Feast" describes the two writers' first meeting, and within a few paragraphs works to portray Fitzgerald as a lightweight drinker and a barroom bore. Elsewhere, Hemingway recalls a conversation in which he reassured Fitzgerald about the size of his manhood — of which Zelda had apparently been critical. Put simply, Hemingway conducts a sustained attack on Fitzgerald for his effeminacy and supposed weakness, contrasting him with his own self-mythologized masculine strength.

The critic and scholar Scott Donaldson, author of the book "Hemingway vs. Fitzgerald," published in 1999, describes the chapters dedicated to Fitzgerald in the memoir as "devastating." He notes that while "A Moveable Feast" is described by Hemingway himself as a "fiction" in the introduction to the work, the book shines a light on the pair's real-world friendship in that it brings to the fore Hemingway's biases and intentions in how he would like his great tragic friend to be remembered.