Dr. John Fryer: The Psychiatrist Who Risked His Career For Gay Rights

The following article includes descriptions of homophobia.

During the 1972 American Psychiatric Association (APA) convention, a speaker was introduced as "Dr. Anonymous." The figure onstage was a massive man wearing an oversized tuxedo and a rubber mask. He gave a speech about what it was like to be a gay man and a psychiatrist, his voice distorted by the microphone to hide his identity. The man under the mask was Dr. John Fryer. This speech has been called one of the most influential moments in LGBT+ history, its impact rivaling that of historic events like Stonewall. Despite this, Fryer remains largely unknown.

Fryer was a psychiatrist. Like more than 100 other members of the APA, Fryer was also a gay man. As stated by the Daily Beast, in the 1960s and early 1970s when Fryer began practicing, a psychiatrist who admitted they were gay would lose their license. Even suspicion was enough to fire someone. This was because homosexuality was considered a mental illness.

First introduced to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952, homosexuality as a diagnosable condition had far-reaching effects. As described by NBC, it legalized many forms of discrimination, such as being denied mortgages and being fired from jobs. It also created the risk of being involuntarily institutionalized and attempts to "cure" a person's sexuality using brutal, cruel, and humiliating "treatments." Dr. Fryer's unusual speech to the APA was a historical turning point, and the first step towards changing how psychiatry viewed sexuality.

The man behind the mask

John Fryer kept the fact that he was Dr. Anonymous a secret from almost everyone, even his close family members and friends, for decades. As quoted by The New York Times, he himself admitted that he had, in just 10 minutes, changed the future of his profession and then vanished from the public eye. The man behind the mask was every bit as fascinating as his onstage persona, and he was far more complex.

A friend and colleague Dr. David Scasta described Fryer as having "bulldog jowls and an impish smile that seems to suggest he just heard the most titillating secret about you; a man who could be witty and charming or petulant and biting: a man with a with a quick, intuitive sense of what others are feeling and at other items, self absorbed and entitled ... as much maligned for his display of sexual orientation as he is praised for his multiple talents."

In his career, Fryer was known as a hard worker and a compassionate doctor, and in his private life he could be the life of the party. While Fryer worked with gay rights activists and did an enormous amount to change the future of the LGBT+ individuals, he often felt like he was not fully accepted in the community.

Fryer faced discrimination from childhood

John Fryer was raised on a farm in Kentucky. As noted by the Daily Beast, his family was a close one. They were known for providing loans to their neighbors in need and for opposing the racial inequality that was rampant in rural Kentucky at the time.

From a young age, it was obvious that Fryer was intelligent. In school, he was even called a prodigy. While academics were always easy for him, interacting with his classmates wasn't. His second grade classmate Betty Lollis told The New York Times that Fryer was the kind of kid who was often made fun of by the other boys.

Fryer started second grade at age 5. At the age of 15, Fryer graduated from high school. As stated in "John E. Fryer, MD, and the Dr. H. Anonymous Episode" at 19 he was on his way to Vanderbilt University Medical School, where he would become one of the youngest students to study psychiatry. In college, he wrote to his parents that he was going on casual dates with women, but his friends have stated that in reality he was seeing men. As adults, many people went to school with Fryer apologized for bullying him. Fryer's relationship with the people he grew up with was a complex one, though. Ms. Lollis stated, "These people that were painful for him were also all he had ... Those are his dearest friends."

Fryer struggled with the idea of homosexuality as a disease

The belief that being gay was a disease that needed to be cured was pervasive and effected everyone. Almost everyone believed that it was true – even people like John Fryer who were secretly gay themselves.

The first version of the DSM, which listed and classified mental disorders, had strict definitions about what was healthy and natural and what was not. As explained at Jstor Daily, any kind of sexual behavior that was not intended to cause a pregnancy was considered deviant and unnatural. In 1968, the DSM II included homosexuality as a diagnosable condition. As described in Psychology Today, this legitimized attempts by therapists to "cure" people of being gay, many of which were painful and humiliating. While Fryer was never subjected to any of these brutal treatments, in medical school, Fryer had to sit through lectures stating that homosexuality was a pathology. In an interview on This American Life, Fryer explained that this insidious belief was very difficult to get over.

Fryer lost his job because of his sexuality

John Fryer was known as a prodigy and sometimes described as a genius. He kept his sexuality a secret, because he feared if he was open about it, he would never be able to advance his career. He is quoted in The New York Times as saying, "It was a way, if you came out as gay, to not have any power. And I wanted to be powerful. So being a straight, closeted physician enabled me to have power."

Despite all of this, Fryer lost multiple jobs because of the bias against gay people in psychiatry. At a private dinner, Fryer confided to a family friend that he was gay. It didn't take long for the conversation to get back to the chair of the department at the University of Pennsylvania, where Fryer was doing a residency. Fryer was told that if he didn't resign, he would be fired.

It was extremely difficult for Fryer to find work after that, and he ended up having to take work that was far below his level of education and experience to finish his residency.

Fryer was part of a community of secretly gay psychiatrists

At the time, the American Psychiatric Association, better known as the "APA," was very socially conservative. While the '60s brought with it a surge of social change, the APA was slow to change. Alix Spiegel of This American Life asked multiple psychiatrists who were members in the year 1970 approximately how much of the APA believed that homosexuality was a mental illness. The answer was over 90%.

That didn't mean that there were no gay people in the APA. As stated by NBC, during annual APA conferences, a group of gay psychiatrists would meet in secret. They began to refer to themselves as the "Gay P.A." These men were challenging the norm in psychiatry by identifying as gay, even socially and only to each other. Despite this, Fryer stated in an interview that he and the other members of the Gay P.A. never even thought of coming out of hiding or challenging their field's perception of sexuality. Fryer stated, "[This was] because of our own internalized homophobia. Most of us probably agreed that it was OK to be a disease."

Fryer didn't believe protesting would make a difference

There were those who challenged the APA's classification of homosexuality as a pathology. The location of the APA's annual conference changed, and in the year 1970 it was held in San Francisco. The gay population there was an active and vocal one, and as described in an interview with gay activist Gary Allender, an APA panel which was set to talk about transgender individuals and homosexuality became a natural magnet for protestors.

Psychiatrists who were at the panel described a group of angry people dressed in extravagant costumes surging into the meeting. The activists shouted and insulted the panelists. Allender explained that they weren't there to be polite or civil – they were there to "delegitimize [the APA's] authority."

This incident upset many psychiatrists at the APA conference, who believed that they were helping gay people by trying to find a "cure." Like his colleagues, Fryer didn't appreciate the protest. Rather than being inspired, he found it embarrassing. Allender has stated that some psychiatrists who were secretly gay had provided him and the other protestors with press passes so that they could get into the convention, but according to Fryer, none of the members of the Gay P.A. were there. At the time, Fryer believed that trying to change the minds of his fellow psychiatrists was impossible. He didn't know that behind the scenes, many younger psychiatrists were working to change many outdated attitudes within the APA – including the profession's view on sexuality.

At first, Fryer refused to speak

While John Fryer didn't know about the more socially liberal undercurrent growing within psychiatry, some gay activists did, and they saw an opportunity to make real change. To do that, however, they needed the help of a psychiatrist who was hiding his sexuality – someone like Fryer.

As stated by NBC, the APA was willing to listen to the gay community for at least one panel during their conference, hoping to put a stop to the protests. At the 1972 APA conference in Dallas, Texas, they had scheduled a panel called, "Psychiatry: Friend or Foe to Homosexuals? A Dialogue." Activists, including gay rights pioneer Kay Tobin Lahusen and her partner Barbara Gittings (sometimes called the mother of gay and lesbian liberation) believed that this could be their chance to change minds at the APA. What they were really looking for was a gay psychiatrist to talk about their experience.

The couple reached out to many secretly gay psychiatrists, including Fryer. In an interview, Fryer stated, "My first reaction was, no way. But she planted in my mind the possibility that I could do something and that I could do something that would be helpful, without ruining my career." The activists moved on and asked every member of the Gay P.A. they could if they would be willing to speak. Every single one said no, because just like Fryer, they knew the risks.

Fryer made his speech in disguise

Finding out that every gay psychiatrist that Kay Tobin Lahusen and Barbara Gittings had been able to find had said no bothered John Fryer, because it was starting to seem like the speech, that the activists believed could make a difference, might never happen. Gittings offered Fryer more and more compromises until she finally made the suggestion that Fryer would accept – he could speak in disguise.

"[Gittings] planted in my mind the possibility that I could do something," Fryer is quoted as saying in The New York Times. "And that I could do something that would be helpful without ruining my career."

Gittings had promised him that he would have a microphone that would disguise his voice, but that wouldn't be enough to ensure that none of his colleagues would recognize him. This was a particular challenge because Fryer was a distinctive man. His friend and colleague Dr. David Scasta wrote that he was 6'4" and around 300 lbs. Fortunately one of Fryer's partners was in drama and helped him to put together a disguise. As noted in This American Life, Fryer and his partner rented what he described as "a large and very flamboyant tuxedo" in hopes of hiding his large frame. To hide his face, they purchased and heavily altered a rubber mask of current president Richard Nixon.

He became Dr. Anonymous

"I am a homosexual. I am a psychiatrist."

These were the opening words of the speech that John Fryer gave on May 2, 1972. He had been introduced as "Dr. Henry Anonymous." His costume was effective, not only at concealing his true identity, but also capturing the attention of every psychiatrist in the room. In his speech, Fryer described his experience and what he had observed of the experiences of fellow gay psychiatrists, who worked hard at jobs that would fire them without a second thought if they knew that they were gay.

In his speech, Fryer told the audience not to allow other psychiatrists to insult gay people without being challenged, or asked to reconsider their bias. He asked them not to let their own biases get in the way when they were met with patients who identified as gay. He also encouraged those among them who were gay to do what they could to change the way gay people were thought of in psychiatry, and to work on accepting themselves as they were – even though it could damage their careers, saying, "We are taking an even bigger risk ... not living fully our humanity, with all of the lessons it has to teach all the other humans around us. This is the greatest loss, our honest humanity, and that loss leads all those others around us to lose that little bit of their humanity as well."

His speech changed minds

Although he had been reluctant to do the speech, John Fryer reportedly left the stage feeling elated. As stated in The New York Times, Fryer was proud to have been able to make the speech when no one else would step up. After Fryer finished his speech, he received a standing ovation from his friends and colleagues, none of whom knew that it was him they were cheering for.

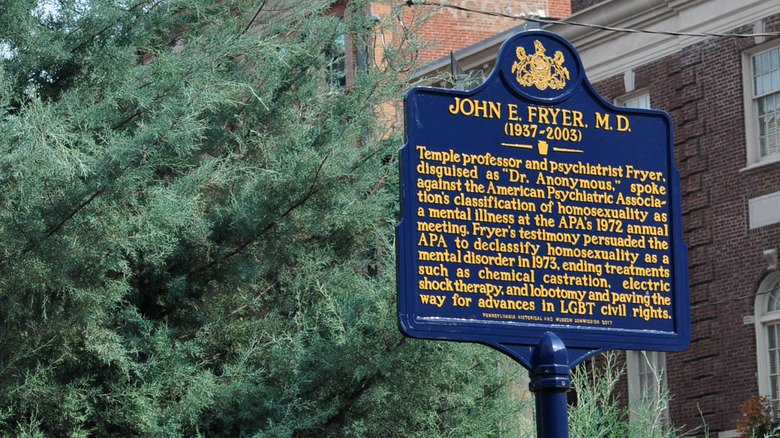

His speech, which was only 10 minutes, would have a tremendous impact on those in the audience, the field of psychiatry, and the future of gay people in America. The year after Fryer spoke at the convention, the APA reversed its position that homosexuality was a mental disorder. Not only did this mean that gay individuals could not be diagnosed and were safe from terrifying treatments and attempts to "cure" their sexuality, it began the reversals to decades of legal discrimination.

It didn't fix everything

Obviously, the world didn't change overnight for gay people in America, and John Fryer still experienced discrimination. In 1973, the same year that homosexuality was removed from the DSM, he lost another job because of his sexuality. As quoted in The New York Times, an administrator told him, "If you were gay and not flamboyant, we would keep you. If you were flamboyant and not gay, we would keep you. But since you are both gay and flamboyant, we cannot keep you."

Although he had contributed significantly to the gay rights movement, he felt he felt isolated from the gay community as a whole. As explained by the Daily Beast, Fryer was not a supporter of pursuing marriage equality. He himself had never been interested in monogamy, or what he saw as an imitation of heterosexual culture, and instead had multiple close friends and partners that he would spend time with. His friend Dr. Scasta stated, "There was always a sense of sadness [for Fryer] at not being fully accepted."

Fryer went on to specialize in hospice care, caring for those who were dying often late into the night. During the AIDS epidemic, he treated HIV+ patients in his private home. When he died in 2003, he was planning a trip to Australia to treat AIDS patients there, too.

He changed the course of history

Dr. John Fryer is still a largely unknown figure, partially because for decades almost no one knew that he had been Dr. Anonymous. In the years before his death, he began to receive recognition for what he had done – but it seemed like he wished he could still be anonymous. He is quoted in The New York Times saying that he felt like he was being "trundled out as an exhibit."

Despite Fryer's apparent annoyance at being celebrated as a hero of the LGBT+ community, he has been accepted as one of the most influential figures in gay rights in the United States. His friend and colleague Dr. Scasta, who was at one time the president of the Association of Gay and Lesbian Psychiatrists, described Fryer's speech as having "a Stonewall riots kind of importance." Malcolm Lazin, LGBT+ rights activist and founder of the Equality Forum, stated in an interview, "I think John Fryer is certainly among the top five figures in terms of their impact on the LGBT civil rights movement. Without him I really do not believe the APA would have removed homosexuality as a mental illness the following year."