Suzanne Lenglen: The Life And Death Of The French Tennis Icon

Even if you have no interest in tennis at all and wouldn't know a double fault if it hit you in the face, you definitely know the names of some of the biggest women's tennis stars. The women of tennis front major ad campaigns, date famous movie stars or musicians, and make the news outside the sports section for any number of reasons. If you've never heard of Serena Williams, then congratulations on waking up from your 25-year coma.

But one of the biggest names in women's tennis ever has sort of disappeared from the public consciousness over the past century. In the 1920s, the Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen was not just the biggest tennis star in the world, she was one of the biggest stars in the world, period. She completely changed the game on every level from women's style of play to the styles they wore while playing. Oh, and she won a truly unbelievable number of tennis matches while doing it.

Today, in honor of her achievements, a court at Roland Garros is named after her, and when a woman wins the singles title at the French Open there, she holds aloft the Suzanne-Lenglen Cup. Here is everything you should know about this amazing athlete.

Suzanne Lenglen's father pushed her tennis career

Born in Paris in 1899, as a child, Suzanne Lenglen suffered from asthma. When she was 12, according to the official Olympics website, her father Charles gave her a gift of a tennis racquet hoping the exercise would help her breathing issues. Instead, he discovered his daughter had a natural talent, and he decided to push it to its limit.

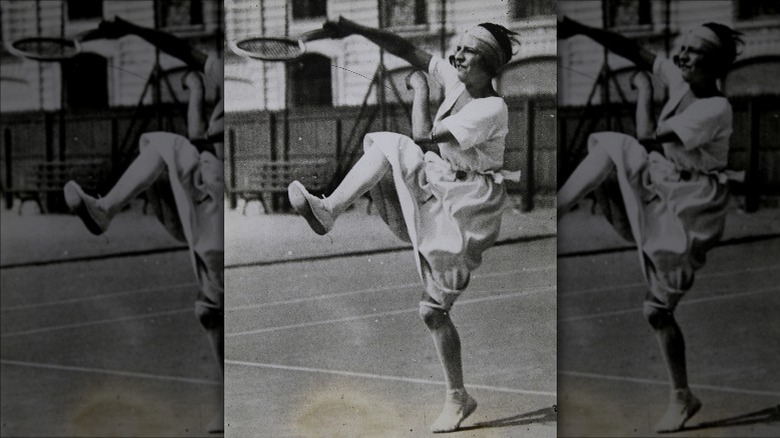

In the early 1900s, the real limit to women's tennis was that it still had to be ladylike. But Sports Illustrated explains that Charles Lenglen was not concerned with his daughter being appropriate, he just wanted her to win. So he taught her to play tennis more like a man, using more speed, harder serves, and other techniques seen only in the men's game until that point.

Like many sports parents, Charles probably went a bit too far. He would scream at Suzanne, calling her "stupid" if she messed up in practice. His presence completely dominated his young daughter's life. Suzanne's biographer, Larry Engelmann, wrote in "The Goddess and the American" (via Sports Illustrated) that Charles was no less than her "father, teacher, trainer, advisor, coach, agent, manager, protector, mentor and, at times, even her tormentor."

She burst onto the scene at the 1919 Wimbledon tournament

Within two years of taking up the game, Suzanne Lenglen was winning some of the biggest tournaments at only 14 years old, per Sports Illustrated. At age 15, she made it to the final of the 1914 French Championships, according to the International Tennis Hall of Fame, although she lost. However, her budding career was rudely interrupted when the world decided to go to war against itself.

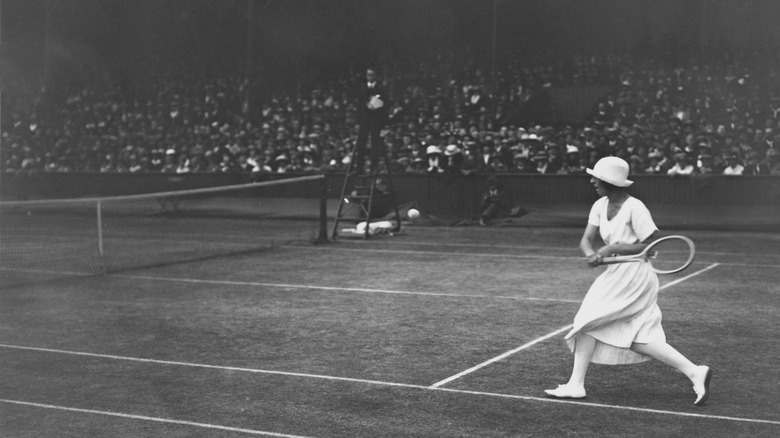

After WWI ended, tennis tournaments resumed. The now 20-year-old Lenglen entered the 1919 Wimbledon tournament and immediately showed the world she was not the child they had last seen play. She appeared on court in an outfit the press described as "indecent": her shirt had short sleeves and her skirt came all the way up to her claves, The Atlantic reports. And her play was more aggressive than ever, just as shocking a scene.

But it worked, and Lenglen made the final against Dorothy Lambert Chambers. Chambers had already won the women's singles title at Wimbledon seven times and was the reigning champion from the last time it was played in 1914, per the International Tennis Hall of Fame. But she was twice Lenglen's age with a more traditional playing style and constrictive garments. Despite managing a comeback in one set that "historians say ranks among the all-time best on Centre Court," Chambers was roundly defeated by Lenglen in three sets.

Suzanne Lenglen's winning streak was astonishing

In "The Sun Also Rises," Ernest Hemmingway describes the competitive nature of one of his characters thusly: "He probably loved to win as much as Lenglen..." (via Sports Illustrated). While someone reading the book today might not understand the reference, at the time it would have been obvious and evocative, as Suzanne Lenglen did little but win.

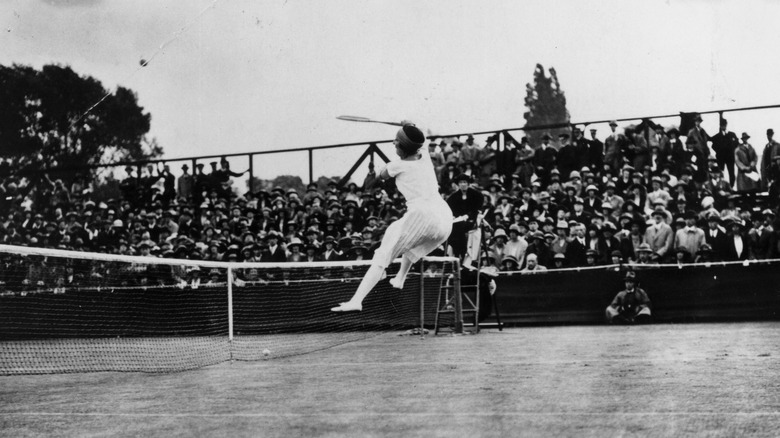

The laundry list of her achievements is too long to fit here, but it's necessary to give some idea of just how dominant a sports star this woman was. After her first women's singles championship at Wimbledon in 1919, she went on to win it again five more times in the next six years. In that same time period, 1919-1926, Lenglen only lost one match total, per the International Tennis Hall of Fame. She held the World No. 1 spot for six straight years, 1921-1926. She dominated the French Championships when they were only open to French players, and once the rest of the world was allowed to enter in 1925, she somehow managed to do even better, winning all three of the women's singles, doubles, and mixed doubles trophies at the championships, not just that year but the next year as well.

Between singles, doubles, and mixed doubles, Lenglen won 250 championships, and that was without ever playing in Australia and only playing in the U.S. once. Seven of her 83 singles titles she won without losing a single game. In all her appearances at Wimbledon, she only lost two matches out of 92 total.

She was a gold medal-winning Olympian

Winning Wimbledon and the French Championship is fine, but are you really an elite athlete if you can't call yourself an Olympian? Thankfully, Suzanne Lenglen got this requirement out of the way early in her career, by competing in the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp, Belgium.

The official Olympics website says that Lenglen came into the Games expected to win, based on her dominant performances on the court the year before. The pressure didn't get to her at all, though, considering Lenglen didn't lose a single game until she made it to the semi-finals, when she embarrassed herself by only winning 6-0, 6-1. And by Lenglen's (and her father's) exacting standards, she had an appalling show in the final, winning the gold medal 6-3, 6-0.

Perhaps all this rapid-fire winning gave her leftover energy for the doubles events, because Lenglen and Max Decugis won gold in the mixed doubles. However, Lenglen and Élisabeth d'Ayen only managed third in doubles, after which Lenglen and her father probably threw her bronze medal into the River Scheldt and banned anyone from speaking d'Ayen's name in their presence.

Suzanne Lenglen became the most famous person in Europe

Today we would expect someone of Suzanne Lenglen's sports prowess to be world-famous, but somehow she managed to do it in a time before the internet or international air travel. France, just emerging very wounded from WWI, raised her up to a national symbol. They called her "Our Suzanne," according to the WTA Tour's official site, while the rest of the world just called her "The Goddess." Sports Illustrated explains that French reporters virtually never said anything even borderline unkind about Lenglen, and the few times they did they got backlash comparable to that meted out by the most devoted stans of celebrities on the internet today.

People went to great lengths to watch Lenglen play. In "The Match of the Century" between Lenglen and another dominant player, the American Helen Wills (the only time they would ever play each other, it turned out), fans paid scalpers the equivalent of $700 for a ticket, per the International Tennis Hall of Fame. Those who couldn't get them climbed trees to get a peek. So many people wanted to watch Lenglen play at Wimbledon that the crowds became a real problem, so the entire tournament was moved to the larger location it still occupies today, just because Lenglen was so popular. Her fame in America in 1921 was comparable only to Babe Ruth.

Lenglen lived like the star she was, too, with a chauffeur and a private train car (the equivalent of a private jet today).

She was a fashion icon

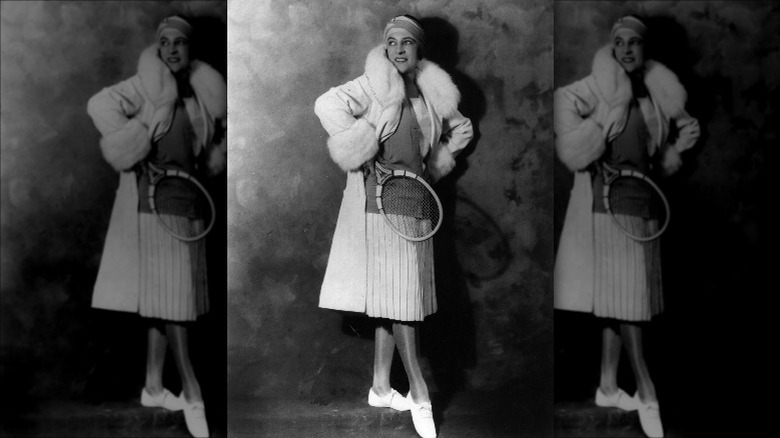

Suzanne Lenglen didn't stop pushing fashion boundaries after her shocking appearance at the 1919 Wimbledon tournament. Even fashion bible Vogue praised her style, writing in a 1926 profile, "the French champion wears a tennis costume that is extraordinarily chic in the freedom, the suitability, and the excellence of its simple lines." Just like today, designers clamored to create her on-court looks, although she usually worked with Jean Patou, one of Coco Chanel's biggest rivals.

Lenglen not only continued wearing "short" skirts on the court, but she donned them with no petticoats underneath, according to Sports Illustrated. Nor did she bother with a corset, which, if anything, seems like it would have made play almost impossible. Her scandalous short sleeves at her first Wimbledon quickly gave way to shirts with no sleeves at all. Instead of boots she wore what we would consider a primitive version of the tennis shoe. The style even became known as "the Lenglen shoe." She wore her hair in a fashionable bob, wrapped in bright fabric.

Some of her on-court style choices didn't stand the test of time, like playing in a full face of makeup complete with bright red lipstick. Nor will you see Serena Williams walking on court in fur coats as Lenglen did. Bill Tilden, a contemporary of hers, described Lenglen's style as "a cross between a prima donna and a streetwalker."

Suzanne Lenglen enjoyed a drink – even mid-match

If Suzanne Lenglen's fame could be compared to Babe Ruth's, then so could her love of drinking. This became a problem when she traveled to America in 1921 at the beginning of Prohibition, according to Sports Illustrated. Doing nothing to downplay French stereotypes, Lenglen wanted to drink wine before she played tennis. But since boozing was made illegal in the U.S. the year before, officials at the Forest Hills tournament told her that wouldn't be possible. So Lenglen informed them that in that case, she was going back to France.

They managed to find her some wine.

But while drinking pre-match might have been controversial, drinking mid-match was something else entirely. At her first Wimbledon final appearance in 1919, Lenglen got tired. Her father, always close by, threw her a bottle of some sort of liquid, which she drank. After that, her play improved and she went on to win. Was it an illegal performance-enhancing drug? No, it was cognac. But the powers that be were not happy about the fact Lenglen kept bringing flasks on court to swig from, per the International Tennis Hall of Fame, so eventually, they told her to stop. To get around the booze ban, she would soak sugar cubes in brandy and then suck on them or dissolve them in her water bottle.

She won the shortest Wimbledon final ever

Suzanne Lenglen did not lose tennis matches. She just didn't. So when she found herself on the losing end of a singles match for what would end up being the only time in an 8-year period, she did not handle it well. According to the International Tennis Hall of Fame, in 1921, Lenglen was playing in the U.S. Nationals when she faced Molla Mallory. The unthinkable happened, with Lenglen getting destroyed in the very first set, losing 6-2. Suddenly – and quite conveniently – she started coughing, and told the umpire through tears that she was so very unwell and couldn't possibly continue playing. Lenglen defaulted the match and left. Sports Illustrated records that she was booed off the court and enraged the tournament officials.

Lenglen would have to face Mallory again quite soon, when they both ended up in the women's singles final at Wimbledon the very next year. It would not be a repeat of America. Whatever alleged cough had been plaguing Lenglen then was not a problem this time. She didn't just win: it was an absolute slaughter. Lenglen beat Mallory 6-2, 6-0, but the score doesn't tell the full picture. The entire final lasted just 26 minutes, still the shortest Wimbledon final ever.

At the net, Lenglen shook her opponent's hand, but she also couldn't help throwing in this dig: "Now, Mrs. Mallory, I have proved to you today what I could have done to you in New York last year."

Suzanne Lenglen could have dramatic mood swings

One word that is used to describe Suzanne Lenglen more than almost any other is "diva." Sports Illustrated says that she won "premier tournaments while demonstrating an attitude befitting a diva." The International Tennis Hall of Fame says she had an "eccentric personality that blurred the lines between superstar athlete and diva." However, the WTA Tour's official site assures readers that she was "not just a diva."

So how did Lenglen get this reputation that has followed her for a century? Well, other than wearing fur coats onto the tennis court, she also had a tendency to fly off the handle. She wouldn't play if she didn't think she looked amazing that day. When refused alcohol in America during Prohibition, Lenglen threatened to leave the country rather than go without wine. Any mistake on the court could make her burst into tears, even if there was no way she was going to lose.

At the 1926 Wimbledon tournament, one of Lenglen's matches was delayed, and she was furious. Why didn't it start on time? Because Queen Mary hadn't arrived yet. So Lenglen, showing who the real queen of tennis was, refused to play at all. It took a male French player going into the women's locker room – blindfolded, of course – and begging her to return to court before she relented.

She was the first female tennis player to turn pro

These days, all the big-name tennis players are professionals, meaning they get paid and aren't just playing for the love of the game. And the biggest tournaments allow those pros to participate, of course. But this wasn't always the case. Until the "Open Era" began in 1968, tennis was a sport for amateurs. There was no prize money awarded for, as an example, winning Wimbledon.

Suzanne Lenglen was an amateur tennis player until 1926 when she announced she was turning pro. Sports Illustrated explains that this was a massive deal, as it meant she could not compete in and win the big tournaments she'd been dominating for eight years. On top of that, the decision made her the first professional woman tennis player ever.

The superstar player explained her very logical reasons for turning pro: "Under these absurd and antiquated amateur rulings, only a wealthy person can compete, and the fact of the matter is that only wealthy people do compete. Is that fair? Does it advance the sport? Does it make tennis more popular — or does it tend to suppress and hinder an enormous amount of tennis talent lying dormant in the bodies of young men and women whose names are not in the social register?" It would take four more decades before the tennis world caught up with Lenglen.

Suzanne Lenglen retired at 28

Suzanne Lenglen's professional tennis career was lucrative, victorious, and short. According to Sports Illustrated, after being paid $50,000 to play a series of exhibition matches in the United States (she won all 38 of them), Lenglen announced she was retiring from tennis entirely. She was just 28, and it was only 8 years since she won her first Wimbledon tournament, but one of her biographers explained (via SI) that while she was still "athletically formidable" she was also "emotionally tattered."

Entering semi-seclusion in her villa in Nice (there are worse places to get your emotions together), it was left to her parents to let the world know what this superstar was thinking giving up her career so soon. Her mother issued a statement that sounds very similar to one you might read today, blaming press intrusion, as she explained her daughter was "fed up with newspaper talk about her and only wants to be left in peace." The official site of the WTA Tour says Lenglen didn't give up tennis completely in retirement, running her own tennis clinic, writing a book about tennis, and even working in a store selling sports equipment.

Lenglen never married, although she had many headline-making relationships. Early in her career she'd been having an affair with a fellow tennis player who was very much a married man, according to Sports Illustrated. After she retired, her father announced she was engaged to a rich American – who was also a married man. Whatever happened there, they didn't end up walking down the aisle.

She died young and mysteriously

Considering she gave up tennis at just 28, Suzanne Lenglen had a surprisingly short time to enjoy retirement. Despite making her career in sports, Lenglen's constitution seems to have been unexpectedly weak. Not only did she have childhood asthma, but Britannica says that an illness in 1924 "interrupted" her career.

In 1934, according to Sports Illustrated, a bout of acute appendicitis almost killed Lenglen. A few years later, while still in her 30s, Lenglen was diagnosed with leukemia. Then she went blind. In June 1938, she summoned her doctors when she felt particularly unwell. They decided to give her a blood transfusion. After seemingly improving for a few days, Suzanne Lenglen died in her sleep on July 4, aged 39. The official cause of death was pernicious anemia, although historians have pointed out this is ridiculous, since the cure for that was simple B12 rich liver extract injections, and this had been understood for two decades by that point. So it is unclear why exactly she died.

Sports Illustrated records that Lenglen's funeral at Notre Dame de l'Assomption in Paris (not that Notre Dame, but a darn impressive church nonetheless) was an event. Both the King of Sweden and the Premier of France sent official representatives. The flowers from admirers filled three cars. According to Find a Grave, she was buried in the City of Paris Cemetery Saint-Ouen. Her grave is a simple but beautiful dark stone vault, with her signature etched in gold at the base. Suzanne Lenglen's final resting place is next to her father's, who predeceased her in 1929.