Being Lovesick Was Considered An Actual Disease In The Middle Ages

"The love that is also called 'Eros' is a disease touching the brain." This isn't a metaphor from a work of poetry or fiction. Instead, it's a line in a medical textbook that was popular in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries, according to the Wellcome Collection. The book in question is the "Viaticum" by Constantine the African, which has an entire section on treating lovesickness (via "Lovesickness in the Middle Ages: The 'Viaticum' and Its Commentaries" by Mary Frances Wack). Constantine the African was a monk and doctor who lived during the 11th century, according to The Conversation. His "Viaticum" was actually a Latin translation of a popular Arabic medical treatise by the Abu Ja'far Ahmad ibn Ibrahim ibn abi Khalid al-Jazzar, a renowned Tunisian doctor, according to Wellcome Trust. The original work was titled "Kitab Zad al-musafir wa-qut al-hadir," or "Provision for the Traveler and the Nourishment of the Settled."

Constantine completed the text for the medical school in Salerno, Italy, but it soon spread throughout Europe. It was especially popular in France. It reflects the Medieval belief that injuries to the soul could affect the body, according to The Conversation, which is why a medical textbook would offer instructions for treating romantic pining. "The medical profession classified this as a physical malady, determined treatments and gave anecdotal evidence of cures," Stanford University researcher Mary Wack told United Press International (UPI).

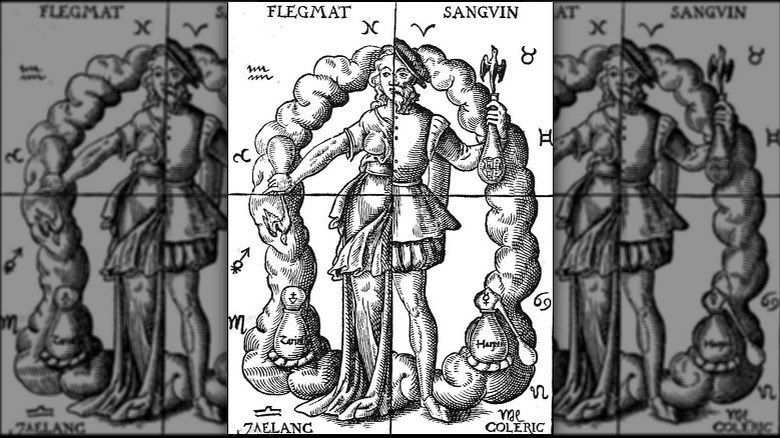

The four humours

In the Middle Ages, physicians believed that health was governed by balancing the four humours. This theory originated in ancient Greece with Aristotle and Hippocrates, but it influenced medical thought for two millenia, according to the Schoolhistory website. The humours were four liquids in the body called blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. The system functioned something like an early Myers–Briggs, with each humour linked to a different personality type. People with more blood were thought to be happy, or sanguine, as Michael C. Ashton wrote in "Individual Differences and Personality" (posted at Science Direct). People with more phlegm were said to be phlegmatic, or calm; people with more yellow bile were thought to be angry, or choleric; and people with more black bile were thought to be melancholic.

It was this last melancholic category that was seen as most susceptible to love-sickness, according to The Conversation. For example, Constantine the African wrote that "sometimes the cause of this love is an intense natural need to expel a great excess of humours." To get rid of the extra bile, doctors prescribed laxatives or bloodletting, according to the Wellcome Trust.

Class and gender

In addition to humoural temperament, the understanding of lovesickness as a disease in the Medieval period was highly influenced by class and gender. At first, only aristocratic men were seen as capable of contracting the disease. It was associated with intelligence and usually afflicted noblemen, according to the Wellcome Trust. Later in the Medieval period, noblewomen began to come down with it as well.

However, the treatments prescribed to men and women were sometimes different. Both could be ordered by doctors to distract themselves with things like sports, food, or music; take baths; and find relief in marriage, according to the Wellcome Trust and UPI. However, men could also be advised to sleep with a number of beautiful women, something that was not on the table for women of the time. Lovesickness as an ailment did not trickle down to the lower classes until the Renaissance, according to UPI. At this point, it spread from the city to the country and from the upper to the middle classes.

Symptoms and cures

So what exactly did Medieval lovesickness look like? Mary Wack told UPI that symptoms could include a dry mouth that tasted like bitter, unripe prunes. Perhaps that's why there were special diet recommendations for curing the affliction. Some suggested foods were ripe fruit, lettuce, lamb, fish, and eggs, according to The Conversation. There were also herbal remedies. Hellebore was one that had survived from ancient Greece. Wack also shared a recipe with UPI, in case you'd like to give it a go the next time you're dealing with an unrequited crush: "'Mix four herbs: dandelion, wild lettuce, honeysuckel (sic) roots and basil. Boil. Add dodder (a parasite). Boil again as long as you would boil an egg," it said.

Some cures could get rather extreme. In one case, a doctor arranged for a patient to be charged with murder. The idea was to distract him from mooning around by forcing him to go on the run. Constantine the African suggested something more wholesome, however: "The cure is judged most perfect if good companions are gathered who are outstanding in beauty, wisdom, or morals," he advised (via "Lovesickness in the Middle Ages: The 'Viaticum' and Its Commentaries). This chill session should ideally take place in a garden or clean, bright rooms, and the patient should avoid getting drunk and, ideally, fall asleep. So for everyone who ever treated their own lovesickness by venting to friends at a sleepover, medieval medicine has you covered.