Parts Of The Bible That Don't Make Sense

The Bible is a foundation of Christianity, and contains texts that are sacred to not just Christians, but also to followers of Judaism and Islam, per Britannica. It is a monumental text, encompassing the very beginning of absolutely everything, a history of humanity's birth and development, how we should conduct our lives, and a telling of what is yet to come. For countless multitudes of people, both past and present, its words were guided by the inerrant hand of God which, for many, can and should be taken literally.

Divided into two halves, the Old Testament and the New Testament, the Bible is believed by scholars to have been first written, in part, from around the 10th century B.C.E., with the most recent chapters scribed in the first two or three centuries A.D. Over the succeeding two millennia, it has been translated and studied extensively.

Nonetheless, for some, the Bible contains passages that are confusing. And for those that try to reconcile it with other historical or evidentiary sources, it can sometimes appear entirely at odds with archeological records — or even itself. Here are some parts of the Bible that don't make sense.

The earliest account of Jesus' resurrection ends with a cliffhanger

The New Testament begins with the gospel of Matthew, and subsequent gospels all share at least some of the stories of Jesus, so it might be reasonable to assume that Matthew is the earliest gospel. Not according to scholars, as James Tabor describes, who overwhelmingly attribute first dibs to Mark — and this particular disciple of Jesus leaves us all hanging.

Central to the Easter story is the resurrection of Jesus. In the gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John, after Jesus' tomb is visited by women to tend to his corpse, we are told they find instead shining angels or men in "dazzling apparel," and, filled with joy and fear, immediately run to tell the disciples of Jesus. Jesus himself wastes no time in making an appearance either, turning up to both reassure the women and let them know his upcoming travel plans to Galilee.

Mark's story, however, ends with an "Inception"-like cut to black, after the women arrive at the large tombstone they'd been worried about moving to get to Jesus' body. Instead, they find the heavy tombstone rolled aside and a young man inside, who calmly tells them that Jesus has risen and is on his way to Galilee, to not be afraid, and to let the disciples know. They don't tell the disciples and they definitely don't rejoice. They flee, terrified out of their minds, and tell no one. And there the gospel ends.

When did Jesus die?

The death of Jesus is a harrowing story. Betrayed by his own disciple and sentenced to an agonizing death by crucifixion, it is held by Christians as the ultimate sacrifice — but when did it actually happen? Considering we know who betrayed him, who sentenced him, and that it occurred during Passover, it may seem surprising to some that biblical accounts disagree on what day Jesus died.

Jesus' death takes place in Jerusalem, which, as Bart Ehrman describes in "Jesus Interrupted: Revealing The Hidden Contradictions In The Bible," celebrated Passover on one specific day, with no allowances for different Jewish denominations. In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus is crucified at nine in the morning and dies at noon the same day, on the day of Passover. The previous day he had shared a Passover meal on the Day of Preparation with his disciples, before his arrest by the Roman authorities. The Gospel of John winds the clock back about one full day, however, with Jesus sentenced to crucifixion by Pontius Pilate at noon, on the Day of Preparation – which Mark tells us Jesus had lived through. As Bart Ehrman summarizes in "Jesus Interrupted," "And so the contradiction stands: in Mark, Jesus eats the Passover meal (Thursday night) and is crucified the following morning. In John, Jesus does not eat the Passover meal but is crucified on the day before the Passover meal was to be eaten."

Who was Jesus' grandfather?

Jesus may be the son of God, but he also had a human 'father figure' in Joseph, Mary's husband. Trouble is, the Bible is not clear who Joseph's grandfather is. The Gospels of Matthew and Luke offer two genealogies of Jesus, and both start with Joseph, but they then immediately differ in the next generation. In Matthew, we are told Jacob is Joseph's father, but in Luke, it is said to be Heli who fathered Joseph.

So why does this matter? As stated by Bart Ehrman in "Jesus Interrupted," "The Messiah is to be the 'son of David,' a descendant of Israel's greatest king." Indeed, the Gospels of Matthew and Luke go to the trouble to not just identify Jesus' "royal blood", but also to document the name of Joseph's ancestors all the way to King David and beyond, with Matthew ending at Abraham, and Luke taking it all the way back to Adam.

One explanation, as detailed in Apologetics Press, is that the genealogy in Matthew relates to Joseph, while Luke's genealogy of Jesus is from his mother Mary's line. But this is still contested, as Bart Ehrman says, "It is an attractive solution, but it has a fatal flaw. Luke explicitly indicates that the family line is that of Joseph, not Mary (Luke 1:23; also Matthew 1:16)."

The Ten Commandments are not so set in stone

As the Bible tells us, 10 commandments were boomed to Moses and the Israelites, and seared into stone by God's own hand. With instructions such as "You shall not murder," "You shall not steal," and none of that adultery shenanigans either, these well-known commandments can even be found in public areas in the U.S., emblazoned in thick stone, as reported by MSNBC.

And yet, the Bible doesn't stop with just 10 commandments, and ventures into some unfamiliar territory with some of the additional laws Moses was given. For starters, as WSFA12 reports, the Bible contains more than one version of the Commandments, with two full sets and another two that partially cover them, or are ritually related. Then, in Exodus 20, as detailed by Oxford Biblical Studies Online, there are arguably 13 statements in the passage from which we derive the Ten Commandments.

This might seem like splitting hairs, but then consider these commandments that Moses is given on the second try, in two brand-spanking-new replacement stone tablets: " "Be careful not to make a treaty with those who live in the land," "Do not offer the blood of a sacrifice to Me along with anything containing yeast," and "Do not cook a young goat in its mother's milk." As Oxford Biblical Studies Online says, "... biblical scholars are not even sure whether the term 'Ten Commandments' refers to what is written in Exodus 20, Exodus 34, or Deuteronomy 5."

There are two creation stories in Genesis, with different orders

The creation of all existence is described in the Bible in neat order but in two significantly different sequences of events. It appears, as Utah State University Professor David Bokovy argues, "it is likely that separate authors with distinct theological views and agendas wrote these myths."

To elaborate, in the first account of creation, Genesis 1, we kick off the universe with the "heavens and the earth," followed by light and darkness — the first day. On day two we get the sky, day three sees plants arrive, the moon and sun pop into existence on day four, and on the fifth day, fish and birds appear. God creates man and woman, along with land-dwelling animals, on the sixth day, and takes the seventh day off to relax.

Then, in Genesis 2, the script is flipped somewhat. We start with a barren Earth, with no plants or water. After watering the earth, from its dust is created the first man, Adam. God then causes plants and trees to grow in his Garden of Eden, places Adam there, and encourages him to "work it and take care of it". Seeing Adam could do with some help, he presents him with all manner of newly created animals to cheer him up, which Adam names. Eventually, using one of Adam's ribs, God creates the first woman — Eve — to finally cure his loneliness.

Abraham was born in a city ruled by people who didn't arrive until a thousand years later

Abraham holds a central role in the Old Testament of the Bible as the first patriarch of the Hebrews, and is venerated by three of the largest monotheistic religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, per Britannica. According to the book of Genesis, Abraham begins his dynasty-building journey from "Ur of the Chaldeans", and, while the Bible gives no actual dates, in the biblical timeline this happens at approximately 2,000 B.C (via Britannica).

Many know Ur as an ancient city of Sumer and Babylonia, which very much did exist from as early as 4,000 B.C.E., but the specific reference to the Chaldeans throws a spanner in the works — the Chaldeans are not even mentioned in historical records until over a thousand years later, per Britannica. It is in the annals of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, who reigned from 883 B.C.E. to 859 B.C.E., that the Chaldeans are first referred to, with their subsequent rule of Ur commencing in 721 B.C.E. — well after the time of Abraham. So, even if the city of "Ur of the Chaldeans" was not the same Ur we associate with the Sumerians and Babylonians, there is still a vast gulf of time separating Abraham from his biblical birthplace.

Noah's flood happened two different ways

The animals came in two by two ... or seven by seven, depending on which part of the Bible's recounting of Noah's flood you read. In the Old Testament, the core premise of Noah's flood is that, after God deems humanity to be too wicked to continue — except for a man called Noah — a great flood is sent to drown the earth. Noah and his family, along with a multitude of animals, ride out the flood in a giant wooden boat (the Ark), and survive to repopulate the planet.

So far so good, overall, but the Bible differs in the specific accounts of this population bottleneck event, interwoven together. For example, in one chapter of Genesis, Noah is instructed to bring aboard the Ark "Two of every kind of bird, of every kind of animal and of every kind of creature that moves along the ground." This might be the version most are familiar with, but in another chapter of Genesis, the requirements shift to seven pairs of "clean" animals, and one pair of "unclean" animals. The length of the flood seems to be unclear also, being described in Genesis as lasting either 40 days or 150 days.

Biblical students have suggested these apparent contradictions in the text are simply different parts of the same narrative, but, as Jeffrey Geoghegan from The Bishop School in La Jolla, California, argues, most scholars ascribe them to two different traditions, that were later brought together.

Everyone was surprised by Jesus' resurrection, even though he told them repeatedly

Even though the specifics vary in the various gospels of the Bible, there is an odd commonality in the reaction to Jesus' resurrection by his disciples — surprise, and doubt. Granted, it comes to them as a very pleasant and joyful surprise, but no one seems particularly blasé about it. However, on several occasions prior to his death, Jesus made it explicitly clear to his disciples that, not only was he going to be killed, he was definitely going to come back to life.

For example, in the gospel of Mark alone, which most scholars agree is the earliest of the gospels (per Britannica), Jesus clearly tells his disciples once, twice, and then a third time that he will be killed, and then rise from the dead, even specifying how soon after his death he would return to life. So it might seem like Jesus gave fair warning that he was going to reappear after his execution, and that perhaps the disciples would applaud him for his punctual return. But the reaction of the disciples, as related in the Bible, is one of shock and disbelief, with one certain doubtful disciple, called Thomas, needing to stick his fingers in Jesus' wounds to be convinced. This is after Jesus performed numerous miracles in front of the disciples, such as walking on water, controlling the weather, and raising the actual dead.

The census that brought Joseph and Mary to Bethlehem didn't happen

As the story of the nativity goes, during the reign of Augustus, a census was called across the Roman empire, that required all subjects to return to their familial lands to be counted. Joseph, the husband of the future mother of Jesus, was said to be descended from the house of King David, and was thus required to travel with his pregnant wife from Nazareth to his hometown of Bethlehem. Along the way, they were guided by a star, and eventually found their way to a stable, where Jesus was born.

But when we attempt to reconcile this heartwarming tale with historical records, there is a snag — as Bart Ehrman describes in "Jesus Interrupted," our records from the reign of Augustus Cesar are fairly good and there is no documented, empire-spanning census during this period. In addition, Erhman points out that this would have required everyone in the Roman Empire to return to their "ancestral home" if — like Joseph — they had thousand-year-old family roots there, which might seem too impractical to make sense. A census did take place in the region where Jesus was born, Judea, by the Roman governor of Syria Quirinius, after 6 A.D. But, as described in "The Census And Quirinius," this was 10 years after the "bad guy" of the nativity story, King Herod, died in 4 B.C.E. (per Britannica).

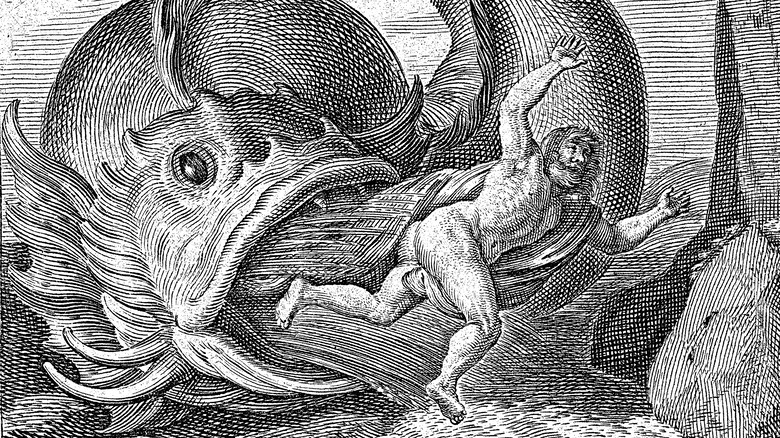

How did Jonah survive being swallowed by a whale?

One of the more enduring tales of the Old Testament is that of poor Jonah and his "whale taxi". Given a book in the Bible all to himself, Jonah's story begins when he is spoken to by God, who instructs him to travel to the "wicked" city of Nineveh to preach, but instead, he hops on a boat as soon as he can to escape his calling. A storm blows up and the frightened sailors throw him overboard, on his advice, since it had become apparent to all on board that the storm had been whipped up by an aggrieved God. Jonah then gets swallowed by a "huge fish," most commonly depicted as a whale (even though whales are not technically fish), which carries him in its belly for three full days, until he is vomited out onto dry land to continue his adventures.

Could a human be swallowed by a whale and survive such an ordeal? As the Smithsonian Magazine describes, this is pretty much impossible. Most large whales are filter feeders, preying on small animals such as krill, and reject anything that does not form part of their normal diet. Even sperm whales, which are big enough to gobble up a person, and do prey on large animals like the giant squid, are lacking a crucial amenity in their belly for any potential live passenger — breathable air.

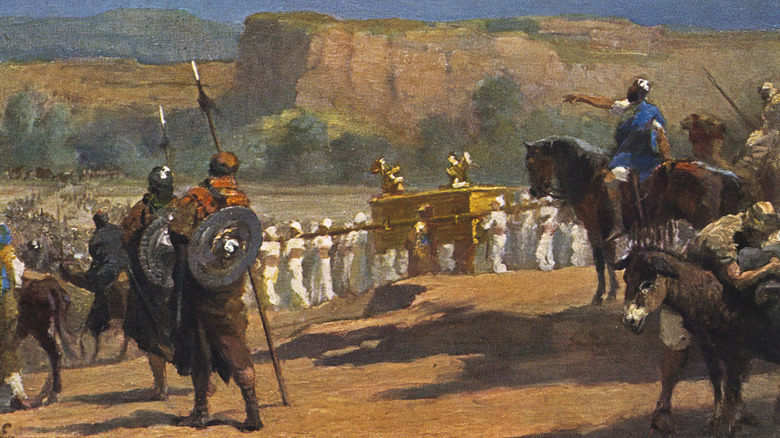

The walls of Jericho were toppled long before Joshua's army arrived

The city of Jericho, located in today's West Bank, is truly ancient, with its origins as a permanent settlement dating back almost 11,000 years, per Britannica. Its famous walls appeared almost as long ago, with evidence of thick fortifications dating back to 8,000 B.C.E., and it is these walls of Jericho that, in the Old Testament of the Bible, are said to have been destroyed when Joshua and his Israelite army arrived — with trumpets.

In the Old Testament book of Joshua, the Israelites arrive at Jericho, promised to them by God. As instructed, after parading silently around the city for six days, they marched once more on the seventh day, blasting the trumpets and shouting, causing the walls to tumble and permitting to the army to sack the besieged city. As described by Maura Sala in Bible Odyssey, estimates for when Joshua conducted this campaign are towards the end of the 13th century B.C.E., as the Bronze age was drawing to a close.

Several archeological digs over the 20th century reveal a different story. The destruction layers found at Jericho — layers of soot and burnt masonry — indicate the city had faced disaster in its past, and the walls were certainly destroyed more than once. However, not since around 1550 B.C.E. had these famous walls been rebuilt — long before Joshua and his raucous army were said to have arrived.

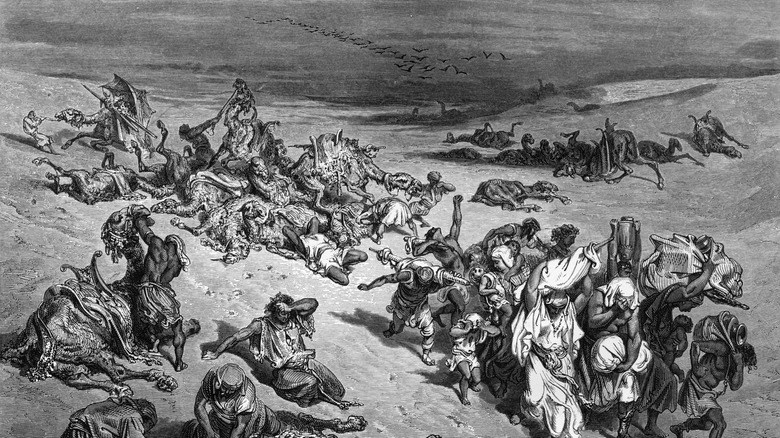

The Egyptians were silent about the 10 plagues that preceded the Exodus

In the book of Exodus, in the Bible's Old Testament, Moses leads the Israelites out of Egyptian captivity to the "promised land," but not after some serious arm-twisting of the Egyptians. The story describes how Moses needed God to bring about ten awful plagues upon the people of Egypt, before the Pharoh relented and set the Israelites free, including rivers of blood, frogs, flies, hail, and, eventually, the divine slaughter of every Egyptian first-born son.

Such is the enormity of these plagues, as well as the socio-economic impact of setting free an entire tribe, that it may be expected for the Egyptians to have documented this reluctant loss of life and free labor. Not so much, as described by National Geographic, with no evidence from written Egyptian records that the plagues, or the exodus itself for that matter, ever took place.

However, there are some tantalizing scraps of contemporary records that support a Semitic presence in Egypt around the 13th century B.C.E, as the Biblical Archeology Society reports, and the Egyptians were not in the habit of recording calamities or defeats that beset them either. So, while scholars of the subject are still divided on the issue of whether there was an exodus, the matter of why the Egyptians didn't mention the 10 plagues remains a mystery.