The Truth Of The Demon Summoning Book The Lesser Key Of Solomon

Cultures worldwide have long-held beliefs about supernatural beings with magical powers, which are now often known as angels and demons in a dichotomy of good and evil. The word "demon," however, has more neutral origins. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, it derives from the Greek word "daimon," meaning a deity or lesser god. The evil association was a later addition by Christianity. The University of Sydney Library notes that in the Christian tradition, the only supernatural beings lesser than God are the angels, with demon coming to refer to fallen angels. Even now, Catholics still consider demons a serious matter.

Demonology, the study of demons, has a long tradition among those who wish to summon them and those seeking protection from them, and "The Lesser Key of Solomon" gives information on both practices. The best-known version, such as the one sold by Akademi Bokhandeln, is only about summoning demons. The full text, however, as hosted by Esoteric Archives, contains five books covering a much wider range of occult knowledge — the Ars Goetia, Ars Theurgia-Goetia, Ars Paulina, Ars Almadel, and Ars Notoria.

"The Lesser Key of Solomon" is also known by the name Lemegeton, Clavicula Solomonis Regis, which translates as "the little key of Solomon the King." Collated by a variety of authors, editors, and researchers, it dates back to the 17th century and contains a collection of arcane sigils and knowledge. The information in the full text is actually more about angels than demons.

Magic spellbooks

"The Lesser Key of Solomon" is what's known as a grimoire or, more commonly, a spellbook. These are arcane texts containing various incantations, secrets, and pieces of ancient wisdom. As the Oxford University Press blog explains, the creation of grimoires is a very old tradition that has since become interwoven with the Abrahamic religions of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. There are numerous grimoires in the world, each with its own distinct history and lore. Notable examples are the "Book of Shadows," which began Wicca, and "The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses" — a founding text in Rastafari.

Most grimoires are known as books of black magic, filled with mysticism about spellcasting and conjuring spirits. As the University of Sydney Library explains, while they're associated with witches, grimoires were more often found in the hands of wizards, sorcerers, and officials of the early church. They also have numerous surrounding superstitions, including the idea that all magical powers are nullified if any money changes hands. Other traditions involve the ideas that a manuscript must be handwritten in red ink and bound in black. Disturbingly, one even calls for a grimoire to be bound in human skin. Grisly details notwithstanding, grimoires were quite popular between the 17th and 20th centuries, which is most of the time the "The Lesser Key of Solomon" has existed.

King Solomon

The Solomon referred to in the title is King Solomon, the ruler of the Kingdom of Israel referred to in the Christian Old Testament and the Hebrew Bible. 1 Kings 3 is all about Solomon, with his fabulous riches and divine wisdom. As About Islam explains, Solomon is also an important figure in Muslim tradition, considered a prophet alongside Mohammed, Jesus, and Moses.

Solomon's importance in the occult, however, comes from legend. A Gnostic text, "The Apocalypse of Adam," is probably the oldest reference to Solomon being able to command an army of demons to do his bidding. The Jewish Encyclopedia elaborates that this was described in more detail by a pseudepigraph, "The Testament of Solomon." It describes how the king was given a magical seal ring by God himself, which allowed him to control a demon who was disrupting the construction of a temple.

While there's scant archeological evidence for Solomon or his ancient kingdom, an entire magical tradition sprang up in his name. Some surviving grimoires are said to have been written by Solomon himself. Ancient Origins mentions two — in particular, the "Magical Treatise of Solomon" and the "Key of Solomon." The latter — not the same as "The Lesser Key of Solomon" — is one of the world's most famous spellbooks, but scholars believe it to date back to the Italian Renaissance, around the 14th or 15th century (via Kalamazoo Public Library).

Book 1: The Ars Goetia

The first and most famous book of "The Lesser Key of Solomon" is the Ars Goetia, often known simply as the Goetia. Delerium's Realm explains how the name derives from the Greek word for witchcraft. The version of "The Lesser Key of Solomon" most people will encounter — sold by bookstores like Barnes & Noble — was produced in 1904 by Aleister Crowley and Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers and contains only this book. It concerns demons, referred to as "principal spirits," and gives elaborate details on them. This version gained notoriety for including demonic sigils (researched by Crowley) that were missing from some other versions.

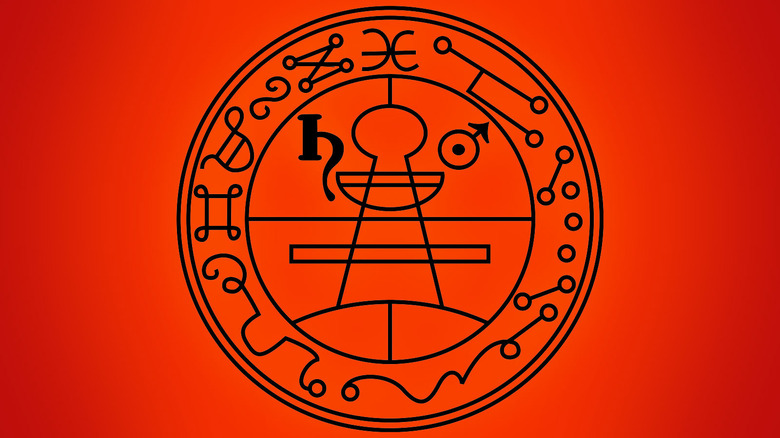

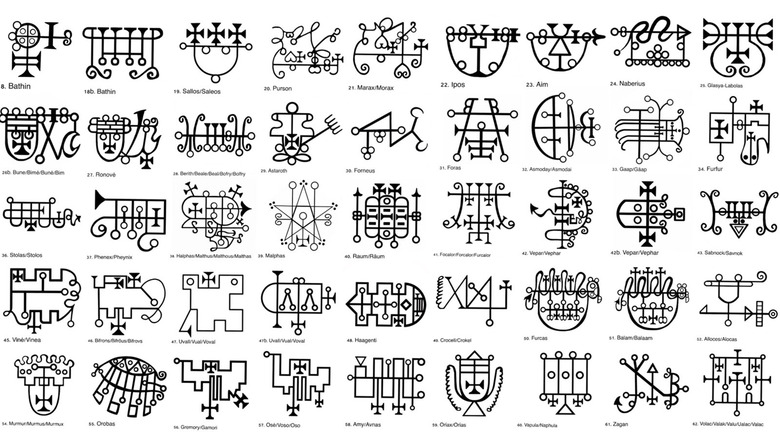

The Ars Goetia gives full descriptions of how to invoke demons, including both ceremonies and spoken incantations. Lengthy orations are given, not only to conjure and command a demon but also to curse a demon who rebels or disobeys. Additionally, a lot of description is given of the demons themselves, each of whom is presented together with their magical seal. The descriptions don't only mention what kind of powers and abilities they have but also their physical appearances and even the way they speak.

The 72 demons

A total of 72 demons are listed in the Ars Goetia, each with their own particular expertise. Naberius, for instance, is said to be able to restore lost honors and make his summoner cunning in arts and sciences, particularly in rhetoric. Buer teaches philosophy and the virtues of herbs and plants. Haagenti can transmute any metal into gold.

The demons also have a hierarchy, with each holding a rank from king down to knight. Any would-be summoner is instructed on which metal to use when creating a seal to invoke the demon of their choosing. A king requires a gold seal, while a lower-ranked demon like a duke or earl requires a copper seal, and a knight can be invoked with a seal made of lead. Confusingly, some require a seal of mercury, with no explanation of how to make a seal from a liquid.

Esoteric Archives notes that the list of demons originates in earlier works like the "Discoverie of Witchcraft" and the "Pseudomonarchia Daemonum." Previous books, however, contained fewer listed demons, with "Pseudomonarchia Daemonium" only mentioning 69. The list was seemingly expanded to 72 to act as an inversion of a list of the 72 angels mentioned in another occult text, the "Semiphoras and Schemhamphorash," which is also attributed to Solomon.

King Bael

Bael is the first of the demons mentioned in the Goetia, hailed as a ruler over 66 legions of infernal spirits. He's described as having a hoarse voice, with the ability to appear in many forms, appearing variously as a cat, a toad, and a man — and sometimes all three. Bael is said to have the power to turn you invisible but will only obey if you wear a talisman inscribed with his sigil.

Other occult texts also mention Bael, including the "Pseudomonarchia Daemonum," written by a doctor named Johann Weyer as a rebuttal against the infamous witch hunter's handbook, the "Malleus Maleficarum." Weyer specifies that Bael appears with all three heads at once. Elsewhere, Jacques Collin de Plancy's "Dictionnaire Infernal" speculates on whether he's the same as Baal, a Canaanite deity. As the Online Etymology Dictionary notes, the name Baal is the same as the first part of the name Beelzebub and has been used generally to refer to false gods.

Other demons in "The Lesser Key of Solomon" are similarly complex, both in appearance and history. The Great King Asmoday, for example, is seemingly the demon Asmodeus who was captured by King Solomon. He, too, is described as having three heads (a bull, a man, and a ram), as well as having a snake's tail, the feet of a goose, and the ability to breathe fire. Despite his fearsome appearance, Asmoday is said to teach arithmetic, astronomy, and handicrafts.

Book 2: The Ars Theurgia-Goetia

The second book, Ars Theurgia-Goetia, is a text about theurgy, the art of asking benevolent spirits and deities for help. The San Diego State University Library mentions that theurgy was once commonly practiced for lofty goals, like wealth and power, as well as for simpler ambitions like winning a court case or escaping arrest. A strong wind was considered a sign of a supernatural presence — something still used as a trope in horror movies and TV shows today.

The Ars Theurgia-Goetia is presented quite similarly to the Ars Goetia, describing 31 spirits, known as "cheife spirits," which can be invoked to help discover secrets and hidden things. These spirits also follow a hierarchy, with each spirit being a king or prince, commanding several servant dukes. Morally, the spirits in the Theurgia-Goetia are more varied, being a mixture of good and evil. The text makes a point of noting which are evil and not to be trusted and which are kind and good-natured.

Book 3: the Ars Paulina

Translating as "The Art of Paul", the Ars Paulina deals with invoking angels and is attributed to the Biblical Apostle, St Paul. It has a distinctly different tone from the more famous Ars Goetia. Where the Goetia talks about commanding and instructing demons, the angels in the Paulina are asked and requested for aid. The angels also seemingly have many more followers, each commanding hundreds of dukes and some with over a thousand servants. Their appearances aren't mentioned, but Biblical angels are said to look no less outlandish than demons. Ezekial 1 in the Old Testament describes angels as being like brilliant blue wheels full of eyes, with four wings and four faces — a man, a lion, an ox, and an eagle.

One thing that the Ars Paulina notes is that there are 24 angels listed, one for each hour of the day and night, with the first hour coming at sunrise. According to the book "The Gods of the Egyptians," Ancient Egypt followed a similar tradition. In the Ancient Egyptian religion, there were also gods and goddesses for each hour. The Egyptians, however, only had 12 hourly deities, whose roles were repeated, both by day and by night.

Book 4: the Ars Almadel

The Ars Almadel details the creation of a square wax tablet called an almadel, which is used to invoke angels. The origins of this text are lost to time, dating back to at least the 13th century. It was once translated from Arabic, but the original text may have been Persian or Sanskrit. The English version, apparently, is somewhat simplified compared to older copies of this text.

The almadel itself is inscribed with protective sigils, set with four candles, and can effectively be used as a portable altar for summoning and consecrations. A synopsis from Abe Books includes the caution that a wizard may find themselves face to face with any number of angels or demons from other planes. Once summoned, spirits are said to appear suspended in the air above the almadel.

The creation of an almadel involves quite a complex and involved ritual, requiring a seal made from gold or silver. Several things need to be taken into account for any hopeful summoner performing the ritual to create an almadel, including carefully inscribing the wax, facing in the correct cardinal direction, using appropriate colored wax, and constructing the almadel at the right time of day. The candles are significant, too — they need to be made from the same wax and be the same color as the almadel itself.

Book 5: the Ars Notoria

The fifth book of "The Lesser Key of Solomon" is the Ars Notoria, which UCLA's Clark Library explains means "the notary art of Solomon." It contains a series of spoken prayers, which is said to have granted King Solomon his deep understanding of science and his legendary wisdom. The orations in this book aim to invoke angels and focus on mental abilities like memory and eloquence. Among them are magic words in Greek, Latin, and Hebrew.

The Ars Notoria dates back to at least the 13th century. There are several different versions still in existence, many of them written in Latin, but the best versions also include mystical drawings known as notae. Researcher Joseph H. Peterson at Esoteric Archives explains that the notae are the centerpiece of the Ars Notoria, and the text is incomplete without them. Some elements in this book, like "Assaylemath, Assay, Lemeth, Azzabue," are very much what many people may expect magic words to sound like. On the other hand, other parts sound very similar to Catholic prayers, though this is likely influenced by the personal beliefs of past translations and edits.

The language of angels

Aleister Crowley's version of the Ars Goetia, as Barnes & Noble mentions, includes some writings in a mystical script known as Enochian. Omniglot gives an example of how Enochian writing looks, explaining that it's used in the practice of Enochian magic. It may appear to be a form of ancient writing, but Enochian didn't exist until the 16th century. The story goes that John Dee, a magician and court astrologer, claimed to have been directly taught the language by angels.

A synopsis from Project Muse elaborates that John Dee was a natural philosopher employed by Queen Elizabeth I of England, and he wrote extensively about conversations he'd had with angels. He went on to devise a system of Enochian magic, named for the biblical figure Enoch. It's described by Ancient Origins as celestial speech, allowing people to commune with angels. Dee's angelic language even has its own grammar and syntax.

Enochian magic went on to be an inspiration to Aleister Crowley, who even wrote a book, "The Practice of Enochian Magick." With its intended purpose being to speak with supernatural beings, it's certainly logical that Enochian magic would tie in with a text like "The Lesser Key of Solomon." It does, however, seem like Crowley made a strange choice to use a language intended to speak to angels but only translate the one book devoted exclusively to demons.

The Seal of Solomon

King Solomon, according to legend, had the power to control demons. The Jewish Encyclopedia explains that this was due to him wearing a magic seal ring inscribed with the name of God. The story, embellished by Arabic writers, states that the ring was given to Solomon by God himself, made from brass and iron and used to compel good and evil spirits, respectively. One legend goes that the demon Asmodeus stole the ring from Solomon, throwing it into the sea to cut off his power. But eventually, Asmodeus was thwarted when Solomon found his ring in the belly of a fish. According to Ancient Origins, Solomon used his ring to interrogate the demons he held under his control, learning their names and abilities as well as how to protect against them. With his ring, Solomon was even able to compel demons to work for him, commanding Asmodeus to help construct a temple. Understandable, then, that Asmodeus would want to throw the ring into the ocean.

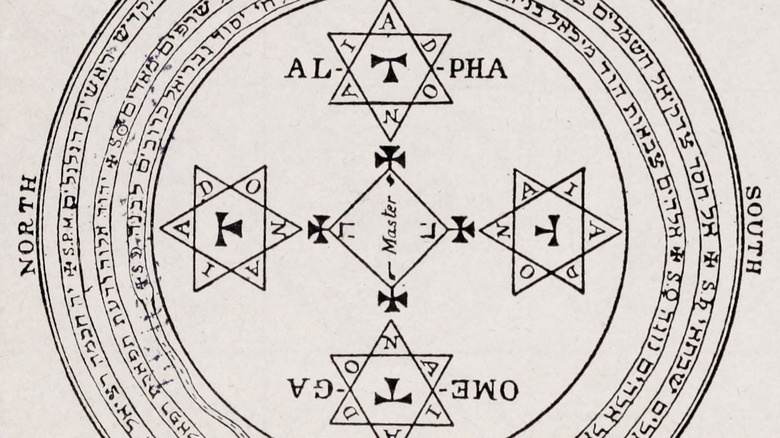

The Seal of Solomon, inscribed on Solomon's magic ring, was a six-pointed star. Britannica explains that this symbol was the predecessor to the familiar Star of David, the symbol of modern Judaism. The symbol had long been used as a protective charm to ward off evil spirits. In the 17th century, the Jewish community in Prague began to use the Star of David as their official symbol, and by the 19th century, it had become adopted almost universally as a symbol of Judaism.