LGBTQ+ Figures They Didn't Teach You About In School

In 2021, Education Week asked teachers what they thought about teaching LGBTQ+ topics in school, and the results were ... well, they were shocking and not shocking at the same time. Only slightly more than half of the educators polled thought LGBTQ+ topics should be taught in schools, and that includes things like landmark court cases, history, and even incidents of oppression, such as the banning of books that feature LGBTQ+ couples.

More than 1,300 teachers and other types of educators were polled, and they were much more likely to respond in favor of teaching other polarizing and sometimes controversial topics, like sex education and racism. It was suggested that part of the problem is a lack of training and available resources for teachers — along with fear of pushback from parents and the community. But here's the thing: Whatever the reason for the hesitation, it means there are a lot of remarkable people being left out of school curriculums — some of whom made world-changing contributions to history, science, civil rights, and healthcare, while happening to be a part of the LGBTQ+ community.

Should their contributions to shaping the world — both in their day and in our present time — be forgotten? Absolutely not. So let's talk about some LGBTQ+ figures who schools might not teach, but that history remembers.

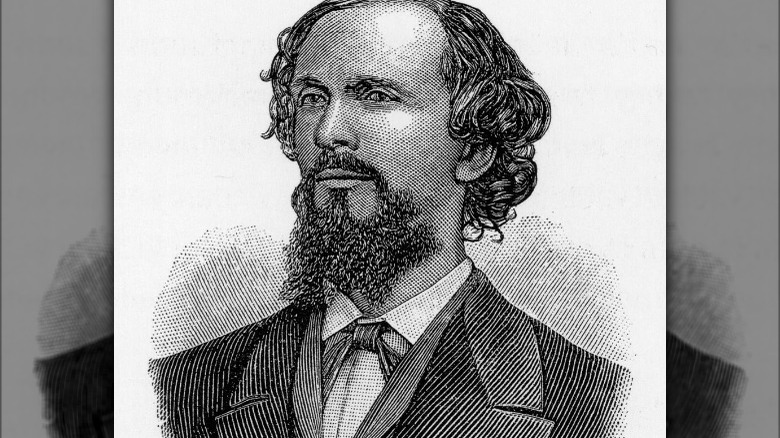

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs

The term "homosexuality" is relatively new: According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, it was coined by the 19th-century psychologist Karoly Maria Benkert. The idea of same-sex attraction goes back much further — at least to ancient Greece and Rome. But the first person to come out of the closet in a very public, vocal way might have been Karl Heinrich Ulrichs.

Rumors of his same-sex relationships had already cost him his career as a lawyer. Still, in 1867 — two years before the word "homosexual" was coined — Ulrichs took on a new legal matter with his campaign to repeal German-speaking Europe's sodomy laws.

According to The New York Times, he was both widely reviled and credited for kick-starting what would become the world's first gay rights movement. His views were, at the time, shocking: Ulrichs campaigned for the equal treatment of people whether they were straight or gay. It was so controversial that at one of the first speeches he gave, he ultimately left the podium to calls to crucify him.

Being attracted to someone of the same sex, he argued, was simply another part of being human. He acknowledged not only gay rights in his work, but also what he called "uranodionism," or bisexuality. In 1879 — just after publishing what would be his last pamphlet — he left Germany and walked across the Alps to a new home in Italy. By the time Ulrichs died in 1895 at the age of 69, he had spent years campaigning for acceptance.

Catharina Margaretha Linck

In 1721, married couple Catharina Margaretha Linck and Catharina Margaretha Mühlhahn were put on trial in Saxony. Their crime? Being lesbians. But it was much more complicated than that.

Social historian Rictor Norton, Ph.D., writes that when they married, Mühlhahn had no idea that Linck — who was going by the name Anastasius Rosenstengel — was actually a woman. Official records claim Linck had spent much of her life dressing as a man, a practice she supposedly started "in order to lead a life of chastity."

Translated transcripts of court documents tell a pretty amazing story (via Historical Perspective on Homosexuality). Linck initially left home and set off with a group called the Inspirants, a religious sect similar to the Quakers in their demonstrative worship. She proclaimed herself a prophet with a direct connection to the divine, but she ended up leaving the group after her prophetic gifts failed in a spectacular way: She promised a rich man he could walk on water, and he found out the hard way that he, in fact, could not.

Linck then joined up with armies in Prussia and Poland as a (male) soldier before eventually abandoning that life for a job with a stocking maker. That's where she met and married Mühlhahn, but it reportedly wasn't long before the relationship turned abusive.

Mühlhahn's mother confronted Linck, discovered she was female, and was probably the one who turned them over to authorities. Mühlhahn was sentenced to three years in prison and exile, while Linck was beheaded.

Robina Asti

Some people are just incredible, and Robina Asti was one of those people — starting with the fact that in 2020 and at the age of 98, she officially became the world's oldest active flight instructor. Asti had been in the air for a long time, and according to The New York Times, she served in the Navy during World War II. She was stationed at Wake Island, got her pilot's license when she was still in her 20s, and in the 1970s — having lived as a man her whole life — began to transition.

She amicably divorced her wife about that time, and in 1980, Asti met the artist Norwood Patton. They married in 2004, and when he died in 2012, Asti had been living a rather uneventful life as a woman for around 40 years. Her birth certificate still listed her as male, though, and when she went to claim her husband's Social Security benefits, she was denied.

Now in her 90s, Asti took the government to court. As a result of her suit, the laws regarding transgender widows and widowers were changed. It actually wasn't the first time she had stood up for transgender rights: Shortly after she transitioned, Asti successfully took on the Federal Aviation Administration for their invasive rules about performing an "internal physical exam" as a part of getting a flight license.

Just a few years before she died in 2021, Asti founded an organization called the Cloud Dancers Foundation, which provides invaluable support to the aging transgender community.

Alan Hart

Born in 1890, Alberta Lucille Hart's young life was shaped by the death of her father, a tragedy that struck when she was just 2 years old. She and her mother moved from rural Kansas to Oregon, and Hart eventually headed off to the University of Oregon Medical School, where she would ultimately graduate at the top of her class. According to Scientific American, that's also where she confided in a professor named J. Allen Gilbert.

She told Gilbert that she was attracted to women and identified as a man. After considering suicide and undergoing therapy and hypnosis in an attempt to become "a conventional woman," Hart opted to have a hysterectomy and overhaul her appearance.

Now identifying as Alan L. Hart, the talented young doctor was first hired by the San Francisco Hospital, but resigned when the press started running headlines such as "Girl Poses as Male Doctor in Hospital." Persecution followed, and Hart would live and work in seven states over the next nine years. Along the way, though, he saved countless lives with the innovative use of chest x-rays to diagnose tuberculosis patients who hadn't developed symptoms yet. Thanks to Hart's work, highly contagious people could be isolated to stop the spread of the disease. Methods pioneered by Hart are still being used in the 21st century.

Hart died of heart disease in 1962, at the age of 71. When his wife died six years later, most of their estate was left to the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon to honor Hart and his contributions to medicine.

William Haines

William Haines was a huge star in the 1920s, and worked at MGM until 1931. He had some massive hits, and at the time, he was heralded as the studio's poster child of the era's ideal man. He was also in a committed relationship with a man named Jimmy Shields — they'd met in New York and moved to Los Angeles together. And here's the thing: According to Slate, everyone knew Haines was gay, and no one cared.

Haines seemed poised for a long movie career, but what happened instead is told in a few different ways. In one version, MGM gave him an ultimatum to break up with his partner or leave the movie industry, and he chose to leave. However, it seems the truth was a bit more complicated than that.

Haines had supposedly negotiated his way around morality clauses before, but only when he was at the height of his popularity in the 1920s. Once the 1930s hit and Haines started to age, he wasn't quite able to adapt to roles that matured along with him, and he was no longer bringing in the bucks. Haines ended up losing his MGM contract, but he hit the ground running. He became a well-known California antiques dealer, doing interior design for some of Hollywood's biggest stars and lending out pieces of his collection for movies like "Gone With the Wind."

Haines died in 1973, still with the same partner who had moved to Los Angeles with him all those years ago.

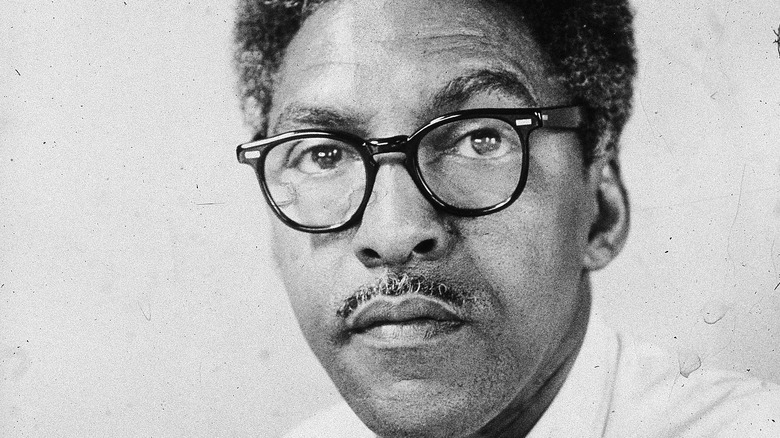

Bayard Rustin

According to History, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was organized largely in response to attacks on civil rights demonstrators in the South. The historic demonstration drew 250,000 people to Washington, D.C., and behind it all was one man: Bayard Rustin.

Rustin was born in Pennsylvania in 1912, in an area where Quaker beliefs in nonviolence were a part of everyday life. He was raised by his grandparents, including an incredibly progressive grandmother who encouraged him to be happy and true to himself — and supported his sexuality. Biographer Michael G. Long wrote, "[S]he wasn't concerned so much about him dating men, she was more concerned about the men that he chose."

After protesting World War II as a conscientious objector, Rustin found himself persecuted — and arrested — for both the color of his skin and his sexuality.

He met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1956, and Rustin would later be credited with helping to cement King's belief in nonviolence. King recognized Rustin as a brilliant strategist, and he was soon a part of King's inner circle ... for the moment. Rustin was ousted after a congressman named Adam Clayton Powell blackmailed King, threatening to spread rumors of an affair between the two men if King didn't call off his plans to protest the 1960 Democratic National Convention.

King went ahead with the protest, but Rustin was forced to resign from King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The SCLC soon found that his contributions were sorely missed, and by 1963, Rustin was again working with King. After the landmark March on Washington, King and Rustin continued to work together, and Rustin kept up his activism after King's assassination. Rustin died in 1987, and in 2013, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

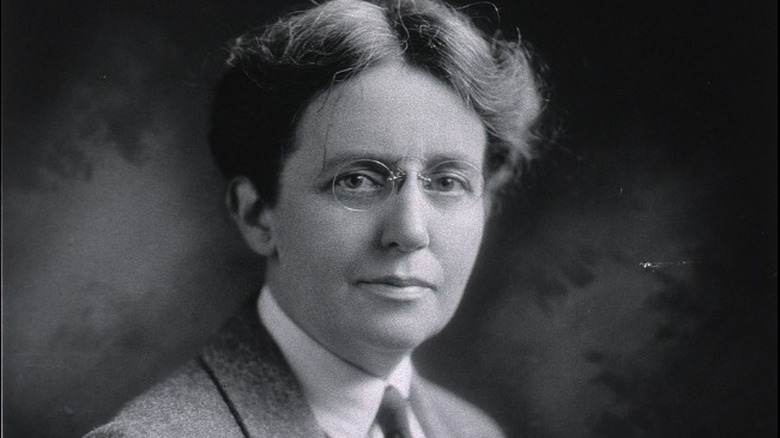

Sara Josephine Baker

Originally a self-taught chemist and botanist, Sara Josephine Baker was the first woman to earn a doctorate from New York University Medical School. She practiced medicine alongside working for the New York Department of Health as an inspector. It was in that capacity that she famously observed that the mortality rate of children born in Hell's Kitchen was three times higher than that of soldiers on the front lines of World War I.

As Curve notes, in addition to being the physician who twice tracked down the infamous Typhoid Mary, Baker was also instrumental in the development of a program to license midwives, and in the creation of a safe infant formula. According to the BBC, she headed up the newly created Bureau of Child Hygiene, developed programs for new parents, and — perhaps most importantly — she went into the tenement neighborhoods herself, something other officials refused to do. (She once described the health department as "reek[ing] of negligence and stale tobacco and slacking.")

It's estimated that her work saved around 90,000 babies in New York City alone, dropping the city's infant mortality rate by 40% in just a few years. She made life better for them, too, scientifically proving the importance of love in raising a child. Oh, and she kicked open the doors of New York universities for other women.

After Baker retired, she moved to New Jersey with her partner, Ida Wylie, and lived there until her death in 1945.

Annie Montague Alexander

Ithaca, New York's Museum of the Earth outlines some of Annie Montague Alexander's many achievements. Born into a wealthy family that founded a sugar cane company in what was then the Kingdom of Hawaii, Alexander was a lifelong naturalist. She became fascinated with paleontology, and financed a series of paleontological expeditions across the U.S. in conjunction with the University of California at Berkeley. She didn't just fund and organize the outings; she went on them — and did the back-breaking labor that resulted in some major discoveries. Alexander is credited with digging up some of the largest ichthyosaur bones ever recovered and even discovering a new species: the marine reptile called Thalattosaurus alexandrae in her honor.

The museum, however, skirts around her personal life, citing a "likely" relationship with her longtime traveling companion, Louise Kellogg.

The Gay Bears Collection of the University of California, Berkeley's archives are more straightforward, lauding the school's benefactor for her contributions to the scientific community. The university notes that Alexander's philanthropy wasn't widely publicized during her lifetime, mostly at her own request and possibly because she didn't want to draw attention to her long-term relationship with a woman.

Alexander and Kellogg met in 1908, and for the next 42 years, they embarked on travels and expeditions that would make Indiana Jones jealous. They would ultimately donate more than 22,000 specimens to the university, and in between all that, they ran their own farm on an island in the Sacramento River Delta. Alexander passed away in 1950, and their farm is now a wildlife refuge.

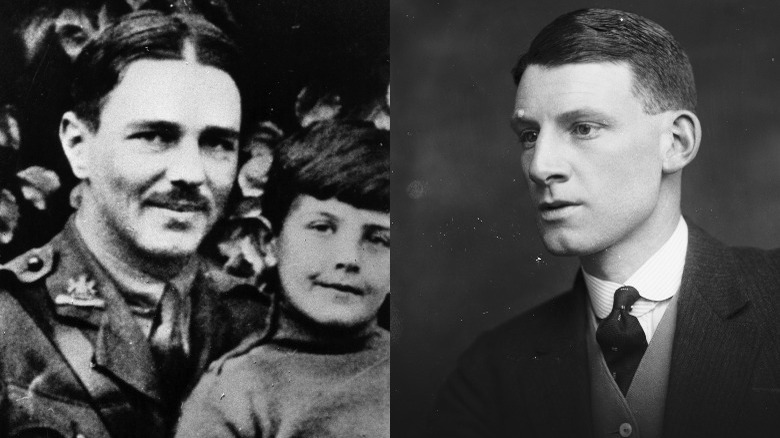

Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon

Wilfred Owen's (left) story isn't a happy one: While he's credited with writing some of Britain's most moving World War I poetry, he wrote most of it in a little over a year. Sent to the front lines in the last days of 1916, he was killed in action in November of 1918. He died just days before Armistice, and according to the Poetry Foundation, he died not knowing that his words would be heralded as painting some of the most vivid pictures of what it was truly like on the front. He also died fighting for a country where being gay was illegal.

According to Forbes, even schools that have their students read Owen's work tend to leave out the fact that he was gay, as was another war poet that Owen met while hospitalized for four months in Edinburgh. That poet was Siegfried Sassoon (right), who The British Library credits with encouraging Owen as a poet and introducing him to other literary figures.

Sassoon survived the war: According to the BBC, he wrote several semi-autobiographical novels after the war and married in 1933, but continued to see other men. He died in 1967, but his story was nearly much different. In the Forbes interview, Kevin Childs, director of the podcast "Love and War," described the end of Sassoon's wartime service: "When a young man he was in love with was killed on patrol one night, he became reckless with his own life until he was wounded during the Somme and returned to Britain."

Marsha P. Johnson

It wasn't until she was 17 years old that Marsha P. Johnson was able to embrace her true self. That, says Tatler, is when she left New Jersey and settled in New York City's Greenwich Village. It was 1966, and she added her middle initial as a reference to what she'd say to anyone who questioned her gender: "Pay it no mind."

Johnson has been variously described as transgender, gay, and — most recently — as gender non-conforming, and while those terms have been debated, there's no denying the fact that she was an activist who made it her life's work to help the city's LGBTQ+ community.

Front and center during the Village's 1969 Stonewall uprisings, Johnson became a familiar figure at Pride rallies, and in 1972, she and Sylvia Rivera founded STAR House. The shelter was created to be a safe space for the city's young gay and trans people, many of whom had been ostracized by their families and had nowhere else to go.

Johnson didn't just give those young people a place to live — she oversaw the development of a sense of community, kinship, and acceptance. She knew how important it was for LGBTQ+ youth to have a safe space: According to Women & the American Story, she had been sexually assaulted as a child.

The body of the community leader locals called "Saint Marsha" was pulled from the Hudson River on July 6, 1992. It wasn't until 2012 that the investigation into her death — originally ruled a suicide — was reopened, and it is still unsolved.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

The Ladies of Llangollen

It's unclear just why there hasn't been a Netflix adaptation of the story of the Ladies of Llangollen. But what is clear is that any adaptation needs to start with the moment Dublin-born Sarah Ponsonby eloped with Lady Eleanor Butler — reportedly by jumping out of her bedroom window and taking her pistol and her dog with her (via the Dictionary of Irish Biography).

That first attempt at running away together didn't exactly work, but the second one did. According to The Irish Independent, the women are thought to be Ireland's first known lesbian couple. They weren't described as such in the 18th century, though. The Wellcome Collection says they were defined as having a "romantic friendship," a term that might have been a little less scandalous than outright saying they were a couple. The National Archives agree, noting that Ponsonby and Butler were always less-than-forthcoming about the true nature of their relationship.

Still, they settled on a Welsh estate they named Plas Newydd, and — along with their Irish maid and devoted friend, Mary Carryl — lived there for the next five decades. They were well-respected, learned, and welcomed countless guests, including Sir Walter Scott, Charles Darwin, and the Duke of Wellington, to their home.

Carryl was the first to pass away, in 1809. Butler died in 1829 and Ponsonby in 1831, and all three were buried beneath a three-sided monument in their adopted homeland.

Willem Arondeus

Willem Arondeus' story starts out in a way that's all too familiar within the LGBTQ+ community. After his parents condemned him for being gay, he left his childhood home in Amsterdam at 17 years old, and never contacted his family again.

By the late 1930s, Arondeus had met and settled down with the son of a greengrocer outside of Apeldoorn, but anyone familiar with European history knows where this is about to go. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Nazi Germany marched into the Netherlands in 1940, and Arondeus promptly joined up with the resistance.

The Philadelphia Gay News says that Arondeus — who had been an artist in his pre-war life — was part of a unit responsible for forging as many as 70,000 fake identification cards for Dutch Jews. When Nazi authorities started double-checking them against official documents kept in an Amsterdam government building, Arondeus and fellow resistance member Frieda Belinfante, who was also openly gay, came up with the plan to destroy the registry building — and 800,000 identity cards stored inside it.

And they absolutely did it, before being turned in by a still-anonymous source.

Over the next three months, Arondeus and 12 accomplices were arrested and executed via a firing squad. Before his death, he asked his attorney to share his final thoughts: "Let it be known: Homosexuals are not cowards."

Lorena Hickok

Lorena Hickok's early life was challenging, to say the least. The Wisconsin-born daughter of a dressmaker and a buttermaker, Hickok fled an abusive home when she was 14. She went from house to house in an attempt to make a living as a maid, flunked out of college, and finally got a job in the society section of the Milwaukee Sentinel. It was there that she found her calling, moving up through the newspaper ranks and being recognized for her skill as an interviewer.

In 1932, she was assigned to cover Eleanor Roosevelt during the presidential election. According to the National Park Service (NPS), the two not only hit it off, but fell in love.

The NPS says that although not everyone agrees about the extent of their relationship, researchers documenting letters that Hickok left to the FDR Library upon her death revealed that they weren't just close — they were in a romantic relationship for at least some of their decades-long friendship.

It was Roosevelt who suggested Hickok become essentially an investigative reporter for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, and in turn, Hickok provided the first lady with invaluable guidance in becoming more media-savvy. They had shared causes — like the struggles of West Virginia coal miners — and they also vacationed together. Hickok was invited to move into the White House in 1940, became Roosevelt's biographer with 1962's "Reluctant First Lady," and passed away in 1968.

Christine Jorgensen

The Bronx-born George William Jorgensen Jr. came into the world in 1926. According to The National WWII Museum, Jorgensen was fortunate to have a grandmother who was incredibly supportive when told that "George" didn't feel like a boy, but instead, identified as a girl.

Jorgensen came of age during World War II, and like many of the era, wanted to contribute to the war effort. After being drafted into the Army during the war and honorably discharged in 1946, Jorgensen's life was forever changed in 1950, after a consultation with the Danish Dr. Christian Hamburger.

Over the course of the next two years, Jorgensen underwent hormone treatments and finally completed sex reassignment surgery. When it was finished, the grateful Jorgensen took the first name of Christine in honor of the doctor who had finally listened and helped her become the person she always knew she was.

Jorgensen's life was filled with extremes: While some lauded the patriotic World War II veteran who embodied not just the advancement of medicine but of American values, she also encountered hatred and discrimination. She went on to become a lecturer in gender identity and a role model for the trans community. Although she died of bladder and lung cancer in 1989, her outlook on life still resonates today.

She wrote: "The answer to the problem must not lie in sleeping pills and suicides that look like accidents, or in jail sentences, but rather in life and the freedom to live it."