Messed Up Things That Actually Happened During Witch Hunts

The belief that witches walked the Earth doing the Devil's work dates back centuries. According to ThoughtCo, witches get a mention as far back as the Hebrew Scriptures (including Exodus and Deuteronomy) and in the Talmud. There was a lull in witch hate around the 10th century, but by 1258 Pope Alexander IV had launched his full-scale crusade against witchcraft. It was no laughing matter, either. No one can really decide how many men and women were executed, but we have records of around 12,000 of them, and historians generally think the number was somewhere between 40,000 and 100,000 people. That's a lot of witchcraft, and a lot of really messed up stuff.

Johannes Kepler had to save his mother

You know you've done something right when NASA starts naming things after you. You've heard about the work of Johannes Kepler, the guy who developed the correct theories of things like planetary motion and magnification. He created calculus (he's probably sorry), figured out how reflections work, and how telescopes work. It's insane to think what else he might have come up with if he hadn't taken some time off to defend his mother against witchcraft charges.

Cambridge professor Ulinka Rublack (via The Guardian) has assembled a complete timeline of exactly what happened to the 68-year-old widow Katharina Kepler, first accused of witchcraft in 1615. Neighbors claimed she was responsible for one woman's chronic illness and for paralyzing one 12-year-old girl's finger. When they claimed she could turn into a cat and accused her of killing animals, it kicked off a trial that lasted six years.

In 1620, Kepler dropped his studies, packed up his family, moved from Austria to Germany, and took over his mother's defense. Rublack says it was his scientific approach to the case that allowed him to pick enough holes in the accusations that he successfully kept his mother from being burned at the stake. There's still a sad ending, though. Considering she spent 14 months chained to the floor of her jail cell, it's not entirely surprising that she died six months after the end of her trial. Still, score one for science?

The Pappenheimer family

While there was a definite belief in witches, there's at least one case where accusations were used as a political tool. According to historian Michael Kunze (via Executed Today), the Pappenheimers, a family of beggars who survived by taking odd jobs, found themselves at the center of a witch hunt in Bavaria, and Duke Maximilian I used them as an example of what happens to those who step out of line.

The entire family — parents Paulus and Anna, along with 22-year-old Gumpprecht, 20-year-old Michel, and 10-year-old Hansel — were accused of various crimes in 1600. Kunze also says (via The New York Times) that Hansel started talking, though, and his confessions became witchcraft. The Pappenheimer parents eventually confessed to all kinds of things, including flying as well as biting a Communion Host and making it bleed. Torture will do that to a person. Investigators even claimed to find potions made from the powdered remains of fingers taken from unborn babies because a good story always plays well in court. They were found guilty, of course, and their execution was nothing short of spectacularly gruesome.

Little Hansel was forced to watch as his mother's breasts were torn off (then put into his brothers' mouths), before they were escorted to the burning site. There, his father was broken on the wheel and impaled on a stake before everyone (except Hansel) was tied to a stake and burned alive. Hansel was executed a few months later.

The Swiss witch and the would-be storm

It didn't take much for a woman to be accused of witchery. One of the common accusations was rooted in the belief that witches could control the weather, which was at the heart of evidence leveled against a woman called Ruschellerin in the 1480s.

She lived in Switzerland (via Washington and Lee University), and despite the reputation of neutral innocence the Swiss would like you to believe, they headed up their own series of witch hunts in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries. With entire chapters in witch-hunting books devoted to bewitched weather, it's not surprising they were blamed for things like the so-called Little Ice Age. Ruschellerin was accused of witchcraft amid claims she had made a horse sweat blood, that she rode wolves, and that she had tried to cause a hailstorm. It's important to note there was no actual hailstorm — the villagers had apparently rung some church bells and thwarted her evil plans — but her neighbors were more than happy to testify she was a witch. She never confessed, though, and was banished from her Swiss town of Reiden. After that, she disappeared from history.

Child gets 6 people executed, lives happily ever after

We all want to believe that karma works in the end, and people always get what's coming to them. Sometimes, karma gets busy and misses a few people.

Scotland Magazine tells the story of Christian Shaw, an 11-year-old girl who caught the family's maid committing the heinous crime of drinking milk without permission. The little girl tattled, and the maid supposedly used the Devil's name in a curse. It wasn't long before the girl was having fits, floating around the room, and coughing up everything from eggshells to hot coals. Supposedly. The girl was encouraged to name her tormentors, and she pointed the finger at 21 men, women, and children. By the end of the trial, three men and four women — including the milk-drinking maid — were found guilty. One of the men committed suicide in his cell, while the others were executed.

And all on the word of a temperamental young girl? Surely, she got what was coming, right? After marrying once — briefly — Shaw teamed up with the wife of the man who had judged her witch trial. They pooled their money and set up the Bargarran Thread Company, using technology the BBC says they stole from Holland and smuggled back into England, ultimately forming the backbone industry of the town of Paisley. She married again, made a boatload of money, and dodged karma completely.

Treves executes the witch-judge

Popular belief says witches were everywhere in Europe, and they could be anyone. The Devil is a sneaky bastard, after all, and during the 1580s, the German city of Trier — now Treves — was packed full of witches. Apparently.

Over the course of six years, 368 witches were executed. That's so many that according to Executed Today, some surrounding towns barely had any women left after they were done with all the torturing and burning. Not everyone was convinced there were that many witches hanging around, but do you know what that kind of thinking gets you? Executed.

Dietrich Flade was a judge tasked with sentencing some of the accused witches, and he was, unfortunately for him, not sure all these people should be executed. Some witches were given light sentences, others were set free, and it didn't take long for him to attract the wrong kind of attention. He was tortured and executed, but according to Cornell University professor George Burr, there may have been another motive. Flade was getting in the way of the political — and witch-hunting — aspirations of the archbishop, who followed up Flade's death with more mass executions. Better safe than sorry, right?

Scottish man insists he's a witch, gets executed

Every witchcraft case has a certain amount of weird, but The Scotsman's tale of Major Thomas Weir and his sister, Grizel, is extra weird. Weir was a fine, upstanding citizen of 17th-century Edinburgh, a devoutly religious, retired soldier who held prayer sessions in his home ... until the day he stood up in the middle of a service and accused himself of being a witch. Others in the community did their best to convince him that surely he must be mistaken, and even the doctors who examined him said he was suffering from some kind of mental disturbance. No one wanted to prosecute him, but he insisted they do and insisted his sister was a witch, too.

She agreed. They were definitely witches. Together, they confessed to an incestuous relationship, said she was marked by the Devil, claimed they'd learned witchcraft from their mother, and said they'd frequently take carriage rides with the Devil.

The people of Edinburgh suddenly felt they had no choice but to put them on trial, and they were found guilty based mostly on their own willing testimony. Thomas was burned at the stake, and Grizel was hanged. Stories of their supposed witchcraft continued to grow. Neighbors said Thomas' staff was sometimes seen running errands in town, and that strange laughter and lights had been seen at their house. The stories surfaced after the executions, though. What the heck?

Christian Caddell and the witch-prickers

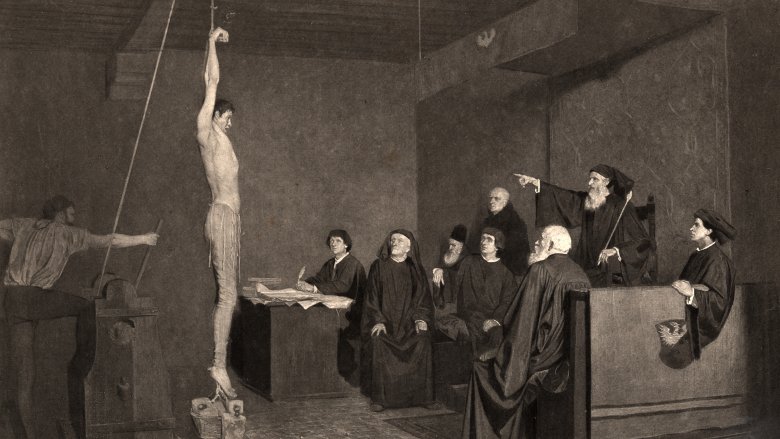

One of the sure signs someone was a witch was the Devil's mark. According to researcher S.W. McDonald (via the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine), different countries had different ideas about what the Devil's mark was, but it was generally agreed to be some kind of abnormality insensitive to pain that wouldn't bleed when pricked with a sharp object. Enter, the witch pricker.

They were tasked with examining accused witches and, well, pricking them with sharp objects to try to find the Devil's mark. Even their contemporaries found them repulsive, and McDonald says there were many who gravitated toward the "profession" because it was a good time. There are instances of witch prickers being imprisoned for unlawful torture and defamation of character, and while most were men, there was at least one woman who decided it was a totally righteous gig she needed to get in on.

According to the BBC, Christian Caddell dressed as a man to strip and shave women before stabbing away with specially made pins. She went by the name John Dickson and made a ridiculously good living. It wasn't until she called out a court messenger for witchcraft that people did a double take, and she ended up arrested, imprisoned, and boasting she just had a knack for reading people. If you think that sounds like witchcraft, you're not the only one — she was accused herself, handed a transportation sentence, and sent to Barbados. No one heard from her again.

Courtroom proves girls are faking, women get executed anyway

Rose Cullender and Amy Denny were Bury St. Edmunds women accused of witchcraft in 1661, and Executed Today says the whole thing started over a herring. After a local merchant refused to buy one of Denny's fish, she was heard muttering as she walked away. Soon after, the merchant's daughter was suffering from fits and lameness. A curse! It didn't matter she was suffering from the lameness and fits before Denny's visit. Those kinds of minor details can be overlooked.

There was another key bit of evidence overlooked at the trial, too. Several other village teens claimed they were cursed, too, and some said they were stricken with clenched fists that would only open when one of the witches touched them. (Cullender had previously been accused of witchery, so accusations against her were piled on for the trial. Two birds with one stone, and all.) When the apparent victims were blindfolded and touched by a few different village women, their hands miraculously opened. Instead of shouting, "Liar, liar, pants on fire," villagers kept shouting, "She's a witch."

The pair were executed without confessing, and the whole trial set a precedent for the Salem witch trials. Since Bury St. Edmunds had accepted so-called spectral evidence as legit, so did Salem. More people died, which is just more proof that kids have always been terrible people.

James VI personally acts as inquisitor

If you think kings and queens would be above this whole witchcraft nonsense, you'd be mistaken. Scotland's James VI (who was also England's James I and the James of the King James Bible) saw dozens of (possibly as many as 200) witches put on trial during his reign, and we're just talking about the area around North Berwick there. According to Historic UK, it all started when he was heading to Denmark to pick up his bride. The entire trip was plagued with storms, and what else could possibly cause storms except witches?

James kicked off a witch hunt, but the details weren't recorded well. We do know he rounded up about 70 women straight away and accused them of dancing up a literal storm on St. Andrew's Kirk. Many died from the torture.

BBC History Magazine says James was so horrified by all the confessions that he decided to oversee the affair personally. He summoned Agnes Sampson to Edinburgh's Holyroodhouse, and when she denied the charges, she was tortured as he watched in "great delight." When Sampson supposedly revealed some intimate details she knew about the king, he became even more obsessed with rooting out these diabolical women. James wrote a book on witchcraft and ordered the publication of Newes from Scotland, a pamphlet designed to add to the witch hype. It worked — Scotland executed around 4,000 witches.

Witchcraft in the French court

It was called the Affair of the Poisons, and according to Clare Colvin and Anne Somerset (via The Independent), the scandal that rocked the court of Louis XIV started in 1676 and didn't end until 34 people were dead.

Historian Benedetta Faedi Duramy writes that it was the French king's fear of finding himself on the receiving end of the poison — and violence that had erupted at his court — that led to the trial of the century. There were a handful of people who found themselves tortured and the like, but since most were commoners, there's no reason to talk about them. Instead, let's talk about Catherine Deshayes, a poor woman who became less poor when her knowledge of poison-making and potions made her hugely popular with a certain sort of person. (The type that wanted someone else dead.) When her home was raided as a part of the king's investigation, they unsurprisingly found all kinds of cauldrons, potions, and ingredients like nail clippings, bone, blood, and all three bodily excretions.

La Voisin, as she was known, was arrested in 1679, and she not only admitted she was into some shady stuff, but that her clientele included the nobility. They were apparently poisoning the heck out of everyone around, so it's not surprising she was burned as a witch in 1680. To be fair, there were probably some actual crimes in all those accusations.

Matthew Hopkins becomes a professional witch-finder

Matthew Hopkins was a weird guy, and Historic UK says he started his witch-hunting career in 1644. He had just moved to Essex when he claimed he'd overheard a handful of women discussing their witchy ways, and of the 23 he accused, all died. (Nineteen died at the end of a rope, plus four in prison.) After that, he proclaimed himself Witch-Finder General, put himself at the head of a group of witch-prickers, and set off to find more witches.

He found lots of them, and anyone with a slightly suspicious personality might think his outrageous witch-finding fee had something to do with it. In just two years, he accused, convicted, and ultimately executed around 300 women, raking in hundreds of pounds. That's lottery-style money in the 17th century.

Hopkins perfected a series of tortures during his work and was known for keeping a suspected witch awake for days to push her to the point where she'd confess. The BBC says there were some serious shenanigans going on, too. Hopkins used knives with retractable blades to convince people his witches weren't feeling pain or bleeding when they were stabbed, and eventually, they say people started to catch on to the fact he was a little shady. History isn't sure how he died, although he's reportedly still haunting Mistley Pond. Cursed by a witch, perhaps? One can only hope.