Here's What The First Major League Baseball Season In 1901 Was Like

1901 was a landmark year in American history. In January, at Spindletop Hill, the first "Texas gusher" of oil was discovered. Then in September, Leon Czolgosz murdered President William McKinley, and throughout the year, the Philippine-American War raged in the Pacific (per the U.S. State Department). Yet, for many Americans, the most important matters of the day were related to Major League Baseball and its 1901 season. The modern era of baseball is largely considered to have begun in 1901, when the American League (AL) officially played its first season (per Britannica), and it was one of the finest in baseball history.

The AL had two Triple Crown winners that year, a feat that has never been repeated since, and has managed to stick around for over 120 years, with their 122nd season starting in April of 2022. Major League Baseball was limited to just 16 teams in 1901, with eight each from the National and American Leagues, but the competition was intense and the rivalries fierce. Let's take a trip back to when baseball was still America's pastime, when echoes of wood bats reverberated through the streets of major cities, and when baseball heroes were still considered common men. Here's what the first Major League Baseball season in 1901 was like.

Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide to the 1901 season

By 1901, Albert Goodwill Spalding, also known as A.G. or "Big Al," had established his reputation as the biggest name in baseball (via the University of Virginia). A former member of the Boston Red Stockings and Chicago White Stockings, and the first pitcher to win 200 games, in 1877 Spalding stopped playing and started establishing himself as baseball's greatest businessman. During this period, he also started to annually publish "Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide," which covered everything baseball-related for the past year. By 1901, his guides were must-haves for any young man looking to try his hand swinging a bat or throwing a ball.

His 1901 guide was over 200 pages long, and packed with baseball info. It started with the history of the game from 1871, had full sections on pitching, batting, and fielding, as well as a synopsis of the pennant race from the previous season. The guide even had a chapter on baseball from outside the United States, with sections on Australia, England, France, and the Philippines. College baseball was talked about, and Spalding included a "Notice to Base Ball Players" informing them of the creation of a "Base Ball Bureau" to help young players play professionally.

Big Al filled the rest of the guide with advertisements for products made by his company, A.G. Spalding & Bros. The ads were for items sold at his stores in New York, Chicago, and Denver, and included baseballs, catcher's mitts, and baseball bats.

The American League played its first season

One of the reasons many fans consider 1901 to be the birth of the modern era of baseball is due to it being the inaugural season for the American League. According to Jules Tygiel in "Past Time: Baseball as History," in the late 19th century, there were several professional baseball leagues, including the American Association (AA), Western League (WL), and the Players League (PL). Both the AA and the PL collapsed in 1891, leaving the National League (NL) as the only consistently profitable professional baseball league.

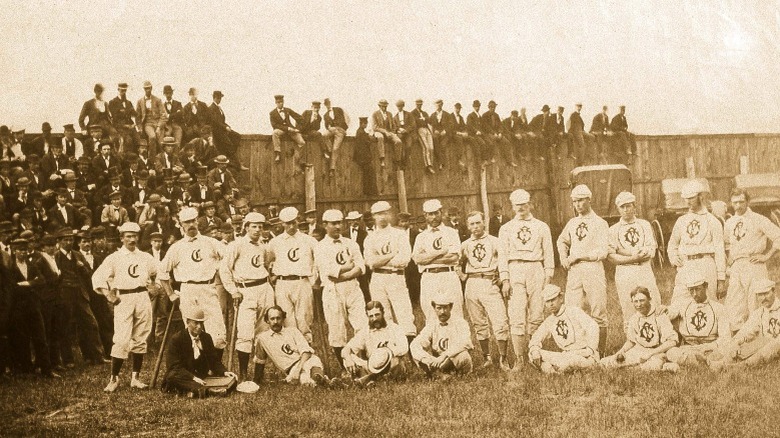

However, in 1900, WL President Ban Johnson announced he was reorganizing the WL under a new name, the American League (AL). The AL started with eight franchises; the Baltimore Orioles, Boston Americans, Chicago White Stockings, Cleveland Blues, Detroit Tigers, Milwaukee Brewers, Philadelphia Athletics and Washington Senators (per History). According to Tygiel, the new league was an immediate success, and overall attendance for major league baseball nearly doubled in 1901. The NL was forced to abandon their commitment of setting salaries at the artificially low rate of $2,400 per season, as the leagues engaged in a bidding war that massively increased team compensation.

The AL was so successful, that the following season they outdrew the NL by nearly half-a-million fans. In 1903, the NL and AL entered into an agreement, which still stands today, whereby the NL recognized the AL as a professional league, and created a three-man commission to rule the sport.

Foul balls became strikes for the first time

One new development for baseball in the 1901 season was that, for the first time, foul balls were counted as strikes. According to Baseball-Reference, the National League (NL) created the foul ball rule at the beginning of the season, because some particularly skilled hitters, like Roy Thomas, had developed the ability to foul off pitches they could not hit for line drives. Thomas would repeatedly foul off pitch after pitch until a walk was forced. This was especially tedious at the time since umpires were typically limited to only a few balls per game, so they would find themselves haggling with spectators for the return of foul balls hit into the stands. One NL manager even started screaming at Thomas mid-game over his use of the tactic (via SABR).

Previously, foul balls were considered meaningless, unless they were caught by a fielder and resulted in an out. Hitters could continuously foul off good pitches but not find themselves behind in the count to the pitcher. The new rule was supposed to penalize players who routinely fouled off pitches, by giving them a strike, and putting them behind in the count. A player still could not strike out on a foul ball though, as it only counted as a strike when there are less than two strikes in the count (via ESPN). In 1903, the American League adopted the foul ball rule, which is still in place today.

Charlie Grant almost broke the color barrier

During the 1901 season, at the height of the incredibly racist Jim Crow era, Charlie Grant nearly broke the color barrier 46 years before Jackie Robinson. According to SABR, the scheme was headed by major league manager John McGraw, famous for leading the New York Giants. In 1901, McGraw took a trip to Hot Springs, Arkansas, to relax and rejuvenate before the new season started, but also to look for ballplayers to fill out his new club, the Baltimore Orioles. During the trip, McGraw met 25-year-old Charlie Grant, a Black second baseman then playing for the Columbia Giants.

Grant had established a reputation for himself as a good fielder and solid leadoff hitter. During his tryout with McGaw in March, he was so impressive that McGraw decided to sign him to a contract. McGraw identified Grant as a Cherokee, not a Black man, to try and sneak him into the league as a player. However, by the end of the month, newspapers had discovered the secret, and the Washington Post outed him in an April 2 article, identifying him by the name "Tokohama."

McGraw ultimately decided against playing Grant in any professional games, as the negative public pressure from fans and rival clubs over a Black player caused him to back down. Grant rejoined the Columbia Giants within a few months and played for them until 1908, and he finally retired from playing completely in 1916.

Minor League Baseball formed after the 1901 season

Today, Minor League Baseball (MiLB) is synonymous with the major leagues, but it might be surprising to learn that there was not always a minor league system for young ballplayers. In the early years of professional baseball, there was a cornucopia of leagues all fighting for supremacy. They were all considered professional, but the level of competition was not necessarily the same. According to MiLB, the first official minor league organization formed on September 5, 1901, and called itself The National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (NAPBL).

The NAPBL was originally made up of 96 different clubs representing 14 different minor leagues. The first president of the NAPBL was Patrick T. Powers, who was also the president of the Eastern League at the time. When the American League and the National League merged in 1903 under the National Agreement, the NAPBL was officially enshrined as a part of professional baseball as the "minor leagues."

Today, nearly every Major League Baseball player spends at least a year in the minor leagues before getting called up to the major leagues, a testament to both the longevity and utility of MiLB. In 1999, the NAPBL officially changed its name to Minor League Baseball, and as of 2008, it drew over 43 million fans annually.

There was no World Series yet

It might sound surprising, especially to baseball fans, but the 1901 Major League Baseball season did not end with a best-of-seven World Series. The first modern World Series was played two seasons later, in October of 1903, when the Boston Pilgrims defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates. According to the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the MLB's first World Series took place just 10 months after professional football's first championship event, which at the time was also called the World Series.

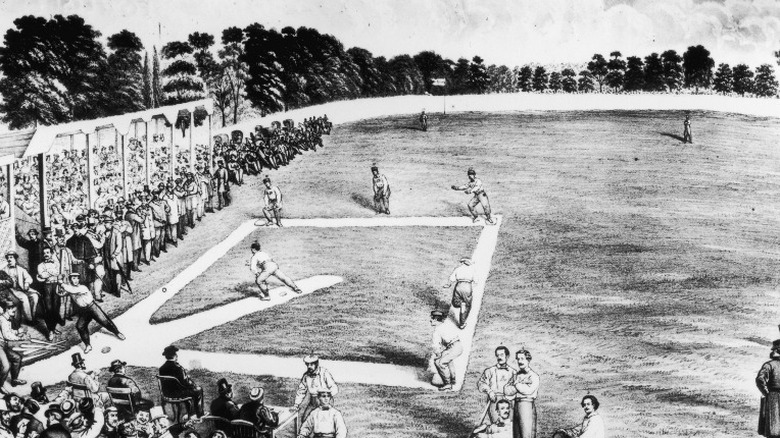

Prior to 1901, there had been other championships for professional baseball, but, due to the shifting nature and constant collapse of professional leagues, there was never a consistent annual trophy. Each league awarded a championship each season to its best team, but there was a lack of long-term agreement between rival leagues to determine the ultimate interleague champion. The first relatively successful attempt was in 1882, between the Chicago White Stockings of the National League (NL) and the American Association's (AA) team from Cincinnati, and each year until the AA's collapse in 1890 they played a similar series (via "The First World Series and the Baseball Fanatics of 1903").

From 1894 to 1897, the first- and second-place teams in the NL faced off in the "Temple Cup," named after former Pittsburgh Pirates owner William Chase Temple, who donated the trophy. In 1900, the top two NL teams again battled, this time for the "Chronicle-Telegraph Cup," which was the last "premodern" World Series before 1903.

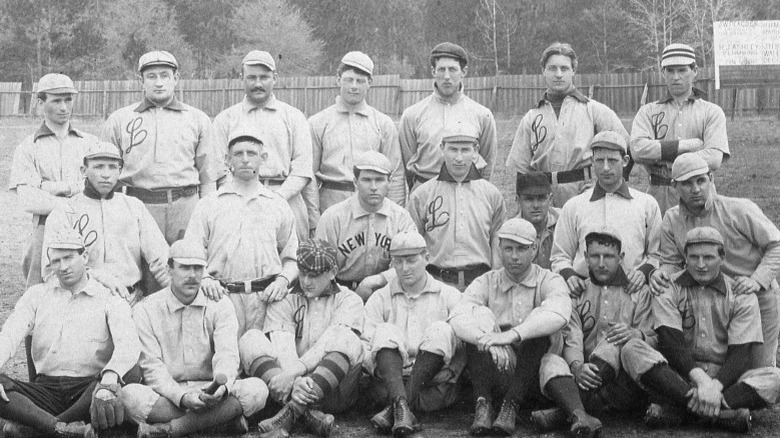

The Pittsburgh Pirates won the National League Pennant

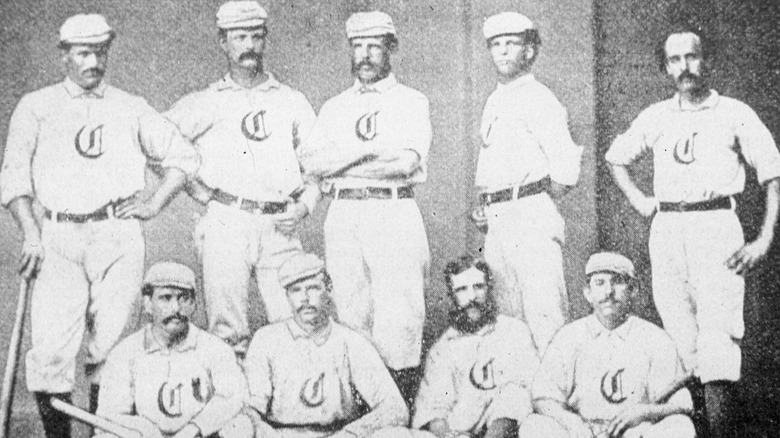

The champions of the National League (NL) for the 1901 season were the Pittsburgh Pirates (pictured above in 1900). They were by far the best team in the NL, and were a full 7.5 games in front of the second-place Philadelphia Phillies (via Baseball-Reference). According to "Spaulding's Official Base Ball Guide" for 1901, "the Pittsburgh team of 1901 was the best governed club — by its president, manager and captain — of any the club had placed in the field in its history."

The Phillies were also one of the best clubs in the league, but dysfunction in April, May, and early June spelled disaster for the club's ultimate record. The Brooklyn Superbas had won the NL Pennant the season prior, but the loss of several key players was too much for them to overcome. The Boston Beaneaters were also hurt by the loss of several good players, including their star third baseman, Jimmy Collins, who defected to play for the rival Boston Americans in the upstart American League.

The Chicago White Stockings won the American League Pennant

The American League (AL) champions for its inaugural 1901 season were the Chicago White Stockings. They finished with a record of 83 wins against 53 losses for a winning percentage of .610 (via Baseball-Reference). Standout second baseman Sam Mertes anchored the White Stockings, leading the league in multiple categories as one of the best hitting infielders in the league. Mertes could be a bit of a hothead though, causing altercations during the 1901 season that caused his ejection from one game, and involved the local police in another, as described by SABR.

The Boston Americans finished second place in the AL, with a 79-57 win-loss record (via Baseball-Reference). In some notable feats, during a May game, White Stockings' players Herm McFarland and Dummy Hoy set an AL record when they belted two grand slams against the Detroit Tigers, who coincidentally also set the AL record for most errors in a game with 12 errors. In June, Milwaukee Brewers pitcher Billy Reid gave up 10 consecutive hits after recording two outs in the ninth inning — another AL record (via Baseball-Almanac).

Cy Young won the pitching Triple Crown in the AL

Cy Young, long considered one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history, had one of his most brilliant seasons in 1901. After spending the first 11 seasons of his career with the Cleveland Spiders and St. Louis Cardinals, in the National League (NL), Young moved to the newly formed American League (AL) in 1901, and signed with the Boston Americans. According to SABR, Young led the league in wins, earned-run average, and strikeouts, a feat now known as the pitching Triple Crown. Young would go on to win the world series in 1903 with the Boston Americans, and in 1937 he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Young was so good, the MLB's current award for the best pitcher is named after him, and 1901 was one of his best seasons (via History).

The top pitcher for the NL in 1901 was Frank George "Noodles" Hahn, who had the best season of his career in 1901, despite pitching for the last place Cincinnati Reds (via SABR). Noodles pitched exceptionally well for the Reds, being the winning pitcher on record for 42% of their victories, an incredible feat that stood as an NL record for 75 years. One of his best performances included a game in May, against the Boston Beaneaters, when Hahn struck out over half the team.

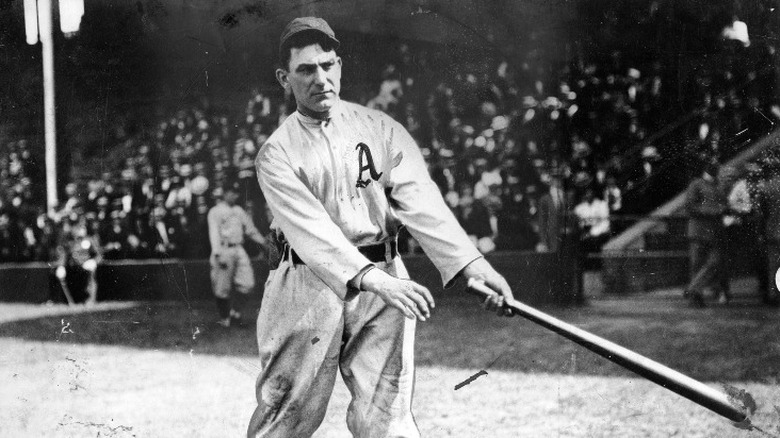

Nap Lajoie won the batting Triple Crown in the AL

Not to be outdone by fellow legend Cy Young, in 1901, Baseball Hall of Fame second baseman Nap Lajoie also won the Triple Crown in the American League (AL), as the league's top batter. Lajoie, like Young, had jumped to the AL during the 1901 season, due to a pay dispute with Philadelphia Phillies owner John Rogers (via SABR). Rogers actually sued Lajoie for signing with crosstown rivals the Philadelphia Athletics, but Lajoie was able to play out the full season as the case made its way through the court system. For the 1901 season, Lajoie won the batting Triple Crown by leading all AL batters in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in, and he also led the league in several other categories as the top batsman. His .426 batting average was still the all-time MLB record by 2022 — 122 seasons later.

Lajoie set a number of personal records during the 1901 season, and his ability to hit the ball for power was 200% better than league average (via Baseball Reference). He was also worth 8.3 wins above replacement, meaning he added eight wins to the team total, over what a replacement level player would have done. This was the highest mark for all position players, and third highest in all of MLB, behind pitchers Cy Young and Christy Matthewson (via Baseball-Reference).

Christy Matthewson won his first game, and pitched a no-hitter

When the 1901 season started, Christy Matthewson was just beginning his standout major league career. Matthewson had started playing professional ball just a few years earlier, in 1898, when he was still an 18-year-old sophomore attending Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania (via SABR.) He joined the National League (NL) in 1900, pitching for the New York Giants, and he made his debut that July, just before he turned 20. His first season was difficult, as he finished without a win and improved pitching statistics.

His next season, in 1901, went much better. Matthewson picked up the first victory of his career, ending the season with 20 of them. He pitched a no-hitter against the St. Louis Cardinals in July, the first of two in his career, and one of the most impressive feats a pitcher can accomplish. He was a top-five pitcher in several of the most important pitching categories, including strikeouts (via Baseball-Reference.) He also hit 13 batsmen during the season, a career high. For the rest of his career, Matthewson would be considered one of the best pitchers in all of MLB. He passed away in 1925, and was one of the first five players elected to the inaugural Baseball Hall of Fame class in 1936.

Players fled the NL for the upstart AL

During the 1901 season, many star players deserted the National League (NL) for Ban Johnson's newly reorganized American League (AL). According to Jules Tygiel in "Past Time: Baseball as History," at the end of the 1900 season, the Players' Protective Association approached NL owners with a new contract, that advocated equal rights for players to terminate their contracts as they saw fit. This was essentially a repudiation of the hated reserve clause, a clause that allowed NL owners to keep the best players on their teams from leaving, to seek better-paying offers elsewhere.

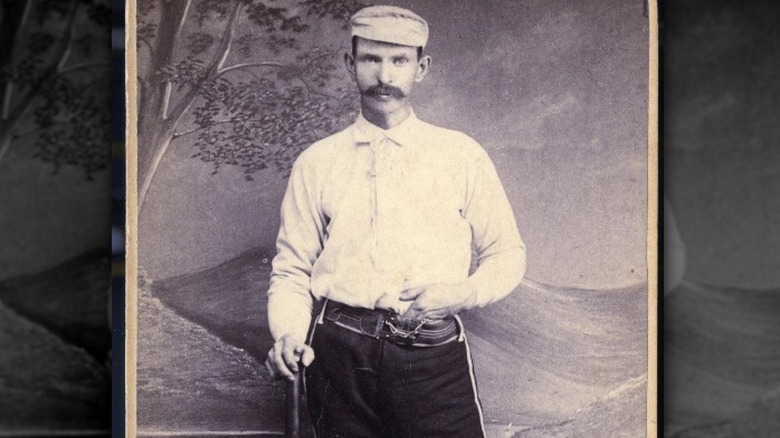

The NL owners immediately rebuffed the contract, but Johnson announced that the AL would honor it — and he offered much bigger salaries to entice players to defect. Consequently, the AL drew an incredible amount of star talent from the NL, with the exception of Pittsburgh Pirates' third baseman, Honus Wagner (pictured above), who remained loyal to the NL.

Two of the biggest stars to leave the NL were pitcher Cy Young and second baseman Nap Lajoie. According to SABR, the defection of a player of Lajoie's caliber was enough to give the AL serious legitimacy as a major league. Lajoie and Young took advantage of the weaker and less established talent that made up the majority of AL, and both of them won Triple Crown titles. Other key losses from the NL to the AL were Jimmy Collins, Joe McGinnity, and Mike Donlin (via This Great Game).

The Detroit Tigers rallied for what is still the biggest 9th inning comeback in MLB history

Ban Johnson's American League (AL) got off to an inauspicious beginning in the 1901 season, when three out of four games slated for opening day were rained out. Yet, for fans in Michigan attending the Detroit Tigers-Milwaukee Brewers game the following day on April 25, the wait was more than worth it. According to SABR, 24-year-old Roscoe Miller was the starting pitcher for Detroit, but by the time he had departed after just the third inning, the Tigers were already down 7-0, mainly due to five fielding errors. By the bottom of the ninth, the Tigers were in a 13-4 hole with little hope of climbing out.

As fans started to make way for the exits, the Tigers finally started to rally. According to SABR, third baseman Doc Casey led off the ninth with a ground-rule double, and he was brought home two batters later by a Kid Gleason single. Ducky Holmes, Frank "Pop" Dillon, and Kid Elberfeld all followed with doubles themselves, each driving in runs. The enthusiastic outfield crowd had to be forcibly pushed back, because they were pressing closer and closer to the baseball diamond, shortening the field. After rallying for more runs, Dillon hit his fourth ground-rule double of the day, scoring Casey and Gleason, to walk off the Brewers. The crowd and the players immediately started celebrating the victory, which is still the largest ninth-inning comeback in MLB history.

The Deadball Era was inaugurated

In 1901, MLB was just beginning what became known as the Deadball Era. This period lasted from 1901 until 1920, and was characterized by good pitching, low scoring, as well as an emphasis on great defense. During this era, pitchers often used whatever was at their disposal to dirty up the balls before throwing them, like spit and mud, but some of them used objects to cut and deface the ball. Pitchers did this because the defacing and dirtying of the ball allowed it to move in uncharacteristic ways, which made it impossible for batters to cleanly hit. Some of the most famous examples of this were pitches known as spitballs, mudballs, shine balls, and emery balls, and they were all devastating against even the best batters.

The Deadball Era came to a tragic end in 1920, after one player died from being hit in the head by a pitch, and umpires started to enforce rules against defacing baseballs, to make sure they were clean and more visible. This made it much easier for hitters, now that the balls had less unpredictable movement and were clearer to see, and they immediately started performing better offensively. Since the end of the Deadball Era, offensive players have started to have more and more success. Power hitting has exploded in 2021 compared to 1901, highlighted by batters like Miguel Cabrera (pictured above), though batting averages and stolen bases have diminished.