The Untold Truth Of La Belle Époque

La Belle Epoque, or The Beautiful Age, is a time period that is sometimes called France's Gilded Age. Taking place from 1871 to 1914, La Belle Epoque incorporated plenty of innovations in transportation, art, science, and fashion, just to name a few disciplines. Led by a long series of fairly weak governments, France was fairly stable during this time.

Paris underwent a massive renovation before and during La Belle Epoque, leading to the city looking much more modern. However, as a result, many of Paris' poor were pushed to the outskirts of the city, which spread outwards. La Belle Epoque showcased further the class divides between upper and lower classes in France, but with socialism not guiding the poor just yet, revolutions were forestalled.

But not everything can be modern avenues and the Eiffel Tower. According to Ruth Ginio and Jennifer Sessions' "French Colonial Rule," France snapped up parts of several different African countries during these decades to use as colonies. Anti-Semitic attitudes towards Jews in France also spread, not helped by the Dreyfus Affair, which occurred when Jewish artillery captain Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of spying for Germany in the 1890s. Therefore, let's discuss the lesser-known aspects of La Belle Epoque.

Despite a series of short-lived, weak governments, France was stable

France's Third Republic was fairly stable, lasting from 1871 to 1940. The Franco-Prussian War of the past few years had destroyed Napoleon III's Second Republic, according to ThoughtCo, and it had brought in a new age. Since no one political party was able to take outright power, the Third Republic eventually succeeded as a democratic parliamentary republic, writes SparkNotes. It was certainly a change from the past several decades of terror and revolution. The Third Republic modernized France in its own way by instituting mandatory schooling, civics education, and compulsory military service; on the other hand, it also seized control of all media coming from Paris.

Still, the Third Republic truly made France into a modern, unified France. People in the rural country read Parisian newspapers, and major issues of the day, such as the Dreyfus Affair, helped to unite the people (via Brown University's Library Center for Digital Scholarship).

The visual arts began to innovate into early Modernism

Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and early Modernism were the art movements of the Belle Epoque. Before that, though, the Academie des Beaux-Arts had exacting standards about what art should look like during the end of the 1800s, according to My Modern Met. But a group of artists banded together and began a new form of art that came to be known as Impressionism. They painted landscapes instead of pulling from the past for their work.

Innovation was the name of the period, particularly as avant-garde art got its start towards the end of the 19th century. Post-Impressionists helmed the art world as the 1890s wore on, and they veered further into symbolic work and artificiality, writes Oxford Art Online. They also emphasized color as its own separate aesthetic aspect of painting.

Vincent Van Gogh, a prominent member of the Post-Impressionist movement, died in 1890 (via Britannica), right in the middle of La Belle Epoque. One of his most famous works that is indicative of the visual arts' evolution during La Belle Epoque is "Starry Night." Claude Monet's "Waterlilies" is another famous work of this period.

The lower class was pushed to living on the edges of Paris

Despite the popular view that La Belle Epoque was the perfect, beautiful age for France, the glory of the period was inaccessible to France's lower classes. During the redesign of Paris, the designer, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, recreated the urban center of Paris into houses that were affordable only for the middle and upper classes. The lower classes (approximately 350,000 people) were pushed into living on the edges of Paris, and the city spread outward rapidly (via Apollone Journal and The Guardian).

According to Apollone Journal, by 1900, less than half of the redesigned urban central housing was accessible to the working classes. As a result, the move to the outer edges of the city happened most prominently between 1872 and 1896, during which time the poor population in that area grew by around 60%. Roads and sanitation were not kept up on the edges of Paris, either, with lack of water being a major problem. In comparison, by 1900, 85% of buildings in Paris' urban center were supplied with water.

Still, some of the working class didn't move to the city's outskirts. Instead, they congregated in the back alleys and side streets of the city, which grew steadily more squalid and overcrowded. For the most part, the lower classes didn't benefit in the slightest from the public works projects that overtook Paris during this time, according to the Apollone Journal.

The number of railways quadrupled in France

The Second Industrial Revolution landed early in France, with such innovations as steel being used on railways due to its durability. As a result, the railways in France grew, and people began to move around more, even growing the country's population.

The Freycinet plan, running from 1879 to 1914, was a public works program that aimed to expand railway connections across France. 181 new lines were built over the course of the program. The lines were intended to have a large impact and were maintained by the state while smaller, more local railway lines began to fade away in the following years, as they were overshadowed by the Freycinet plan rails. The railways were also mainly built in areas that were underserved, with the overall goal being to unite France further, according to Olivier Lenoir's "The Belle Époque of the railways." Overall, Lenoir found that the populations of now-connected areas did increase, as did France's overall revenue.

French West Africa, while growing, was constantly rearranged

During La Belle Epoque, France spread its colonial influence into Africa, conquering many territories. Renamed French West Africa, the area was in flux, with people and places being reorganized constantly. According to World Atlas, the larger scramble for Africa among European countries was taking place during this time, and France didn't want to be left out; it would ultimately colonize large parts of West and Equatorial Africa (via "French Colonial Rule").

Stephen Wooten writes in "The French in West Africa" that France mainly dealt in the Senegal River area during this time, expanding into the eastern interior during La Belle Epoque under the newly-created post of Governor of Senegal. From the start, the French government appointed military commanders to oversee its African interests. Partly due to resistance from a few African empires such as the Almamy Samori of Wasulu, French West Africa was politically, socially, and economically disorganized during this time.

Through the end of the 1800s, France continued to expand its presence in West Africa, though it did not begin to focus on productivity until the next century. The French eventually expanded further north into Morocco, Algiers, and Tunisia (via Britannica). That said, the French focused on direct control over the African people instead of assimilation.

Anti-Semitism spread in France

Jewish artillery captain Alfred Dreyfus, writes History, was falsely accused of spying for the Germans in 1894. After a period of imprisonment, Dreyfus was eventually exonerated of his crimes, but the event was major enough to be officially named the Dreyfus Affair. It deeply divided France over Dreyfus himself, politics, national identity, and religion, which also spread anti-Semitism deeper throughout the country. Catholics had kept anti-Semitism alive for centuries by relating charges against the Jewish people, but they took a new turn during La Belle Epoque.

Anti-capitalist sentiment was also now the name of the game in regards to anti-Semitism. Even before the Dreyfus Affair, writers were using their power to spread accusations against Jews. According to Dreyfus French Culture, Édouard Drumont, a French journalist, founded an anti-Semitic paper in 1886 in which he denounced 140 Parliament members, attributing the corruption to Jewish financiers. He sold nearly 150,000 copies, and his work mainly consisted of different versions of anti-Semitism. He continued his diatribe by complaining about features that were thought to be explicitly Jewish, such as an immunity to plagues and soft hands. This was all compounded with a view of social mobility as dangerous for an established society such as France, and so people worried about Jews being able to rise through the social ranks.

There was wary uncertainty surrounding Germany's leadership

Many French people treated Germany's policies with confused wariness in the decades before World War I. But this was complicated by domestic politics, so Jean Jaures, who led the Socialist wing in the Chamber of Deputies, aimed for cooperation with the French bourgeois left. He saw a possible war in the future, writes Britannica. As more time passed, the clearer it became that he was right; some wariness was more than warranted.

The intellectuals in France were especially uncertain of Germany's leadership. In 1911, Germany sent a gunboat to Morocco, one of France's territories. Then-leader of the Chamber of Deputies, Joseph Caillaux, attempted to pacify Germany by offering them a piece of the Congo region. Most Frenchmen were outraged, and Caillaux was ousted in January of the next year. Raymond Poincare succeeded him and began beefing up the army in preparation for a war Germany was thought to want. Though those with nationalist sentiment were pleased, the socialist contingent still hoped for an appeasement with Germany (via Britannica). The left, who opposed nationalism and favored some kind of compromise and collaboration, won the next election. However, there was little chance for compromise, and when war did break out in August, a spate of nationalism rose in France — aimed against Germany.

Vehicles made the shift from carriage to car

During La Belle Epoque, carriages gradually made way for early cars on the streets of Paris. According to Classic Cars Journal, La Belle Epoque saw the final iterations of horse-drawn carriages, many of which were beautifully designed. French automobile designer Ettore Bugatti worked in both the carriage and early car industries. Bugati designed the 1913 Peugeot BP 1 Bebe, which was designed for Germany but built for the French market; it was the first of the Peugeot company to sell over 3,000 units.

France and Germany were the first nations to enter the automobile business, writes History, though America and Japan eventually took the lead. (That said, the first real automobile was the 1901 Mercedes, made for Daimler, a German company. Daimler rose as a company throughout the decade, and by 1909 employed 1,700 people, producing just under 1,000 cars a year.)

ThoughtCo writes that the chemical, iron, and electricity industries also grew over the course of La Belle Epoque, in part due to their work for the innovation happening with automobiles and aviation.

Paris was redesigned

Paris was redesigned by Georges-Eugène Haussmann in the 1800s. He effectively created the modern Paris (though he also displaced thousands of Paris's poor, writes The Guardian). Thousands of buildings were built — such as the famous Paris Opera, immortalized in the "Phantom of the Opera" — and thousands were torn down.

It started back in the 1850s when Emperor Napoleon III reflected on Paris' dingy squalor, wondering why it could not be redesigned to be more like London, which had long avenues and a sewer system that filtered out the diseases that were overtaking Paris at the time — namely, cholera and typhoid. Haussmann interviewed with France's interior minister, Victor de Persigny and got the job after proudly showcasing his accomplishments. Napoleon III then showed Haussmann a map of Paris with three straight lines running through the middle of the city. Napoleon III wanted wide avenues, and Haussmann obliged, even if he had to tear apart the heart of the city in the process.

According to BBC and The Guardian, though Haussmann either quit or was made to resign in 1870, work on his plans continued until the 1920s — after the end of La Belle Epoque. Overall, city squares, parks, and a new aqueduct, as well as other buildings and areas, were built. With the addition of the massive railway project occurring at the same time, Paris looked like a new city when everything was finally finished.

Material consumerism had its beginnings

The Second Industrial Revolution allowed more of France's lower classes to acquire material belongings, since factory jobs meant they could pay for them. As a result, consumerism as an economic concept began in earnest.

Anais Albert's "Working-Class Consumer Credit During the Belle Époque: Invention, Innovation, or Reconfiguration?" writes that agents from retail chains began peddling their wares to people at home during La Belle Epoque, working specifically on credit. If consumers didn't pay what they owed on time, they could be fined part of their salary, as decreed in a procedure authorized in 1895. The period thus saw the revolution of the consumer-creditor relationship.

Mass consumption was both feared and anticipated; it was thought to throw the social order into upheaval, but also many workers now had more money to spend, just not in cash. Though this relationship was once seen as a massive change, now it is thought to be more of a restructuring of economic policies. In short, modern credit was essentially created during La Belle Epoque.

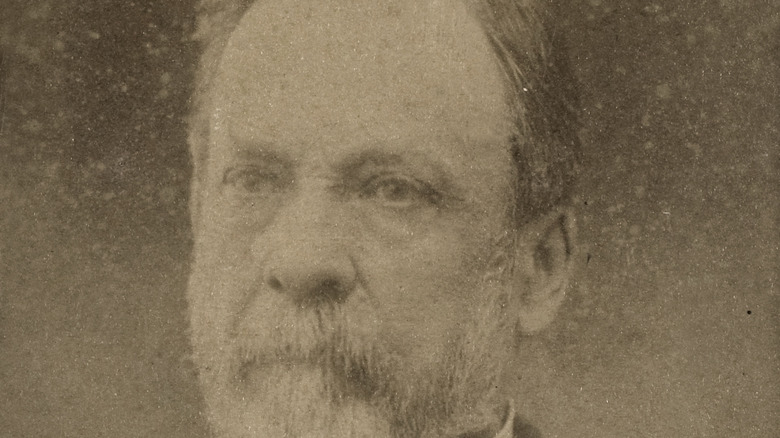

Louis Pasteur innovated heavily in the medical field

Among other innovations in the sciences, Louis Pasteur developed vaccines for anthrax, fowl cholera, and rabies, though his accomplishments are even more widespread. According to Science History, Pasteur adopted germ theory when scientists were still arguing over its own validity. While researching, he discovered the aggressors of France's then-significant silkworm blight. In the early 1870s, Pasteur concluded negotiations with the new government and was funded with a new laboratory so he could freely study disease.

Though he began his scientific work before La Belle Epoque had begun, Pasteur did discover how to induce a vaccine during the period. He first worked with fowl cholera, only discovering the process after he had left a cholera culture alone for a time and it had died; he decided to use it anyway, and he found that time had allowed the microbe to reduce, therefore not giving chickens illnesses. Pasteur used the same method for other diseases in animals — and later rabies in humans — and was successful (via Science History).

Britannica writes that Pasteur ultimately contributed to the creation of immunology. His work on rabies, first conducted on rabbits, and later on humans, was his final medical success, though, as his health began to fail and he suffered from worsening paralysis after his 70th birthday.

The French fashion scene evolved into the beginnings of modern haute couture

The fashion scene during La Belle Epoque tried to blend old and new with its designs. Fashion as an industry also rose during this time, partly due to the era's prosperity; the rich and well-to-do wanted and could afford new fashions, writes the Claus Jahnke Collection. Parisian haute couture began to be responsible for trends that were quickly copied around the world, such as the "Gibson Girl" look for the active woman. Bright colors, empire waistlines, and small silhouettes were the fashion of the day.

Quite a few names took center stage in this regard. Varsity writes that Jacques Doucet was the first to start a ladies clothing salon in 1871. He created dresses that emphasized both new styles and took inspiration from old ones. The House of Lucile similarly began creating gowns that emphasized sensuality. The English House of Worth also worked new opulent necklines into older styles. Charles Frederick Worth used feathers, pearls, and gold ornaments to emphasize indulgence and beauty. Dress silhouettes were constantly shifting.

Clothing on models also came about during this period, as fashion as an industry really began gaining its legs. Fashion shows began to be held, and clothing was constructed much more for the general consumer than for one person in particular (via Varsity). La Belle Epoque appreciated both the present and the past, and brought new concepts into the young fashion industry.