Here's What It Really Means To Commit A War Crime

Wartime atrocities are as old as war itself, but the concept of a war crime is a new invention. The term "war crime" is rooted in an Enlightenment-era reconfiguring of old-school European Just War Theory. While for much of history wars had been moral or immoral, Enlightenment philosophers Hugo Grotius and Emer de Vattel proposed a concept dubbed "the state of war": an amoral landscape governed not by any ordinary moral code but by a set of laws all its own (via Virginia Journal of International Law).

All war was presumed to be just, governed only by the laws of war. Prior to this philosophy, wars could be just or unjust, and criminal acts were just that — criminal acts — prosecuted under ordinary criminal law or otherwise punished by retribution according to the often-unwritten set of norms known as the laws of war. Within the state of war, however, acts that were not protected by the laws of war (or violations of such unwritten laws) could justly be treated as criminal infractions of a larger kind and unique class: war crimes.

The First War Crimes Were Committed by Confederate Generals

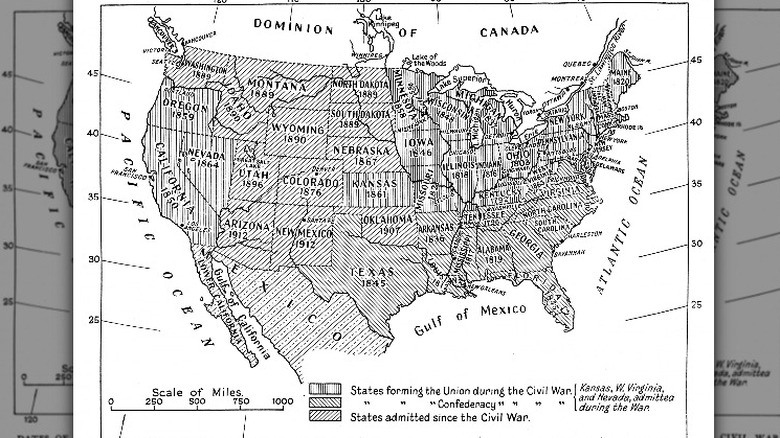

In the mid-19th century, this style of thought — that the ethics of war were governed by their own code that fell under the jurisdiction of extant legal powers when they were violated — took hold. It was a useful idea seized upon by jurists and judges in the United States, and a potential solution to dilemmas first posed by the Mexican-American War and now at a climax with the Civil War in 1861.

While attempting to prosecute Confederate officials for wartime offenses (generally reserved for foreign leaders) during the Civil War, the Union was stymied by a legal roadblock: the Confederates' Constitutional rights as Americans citizens (including the right to trial by jury in ordinary criminal courts). Abraham Lincoln, an astute lawyer, solicited the help of Franz Lieber, a prominent jurist and gymnastics enthusiast, to author a set of principles specifying new criminal codes specifically pertaining to war (via Virginia Journal of International Law). The Lieber Code, adapted in 1861 and distributed in 1863, was considered the framework for the multitude of wartime codes that would follow it (via History).

A 19th-Century Movement Invented Internal Wartime Law

The movement toward international wartime law was also budding in Europe, where the first Geneva Conventions were introduced in 1863, followed by a half-dozen additional assemblies on the subject over the years. The Kellogg-Brand Pact banned war as a tool of national policy in 1928 (via U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian), then the Nuremberg Charter of 1945 kicked off the first international wartime tribunals at Nuremberg and Helsinki after World War II (via Britannica) by codifying new terminology like "crimes against the peace."

Modern international wartime law as we know it today is founded in the Geneva Conventions of 1949 (as well as Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions added in 1977). These documents among a myriad of others comprised the legal framework for the Rome Statute, which was written in 1998, and which 123 nations ratified prior to the creation of the International Criminal Court, where war crimes are tried today.

Established in 2002, the ICC has jurisdiction over 123 member states — a number that does not include China, Russia, Ukraine, or the United States (via Human Rights Watch, NPR). Unlike its UN-operated counterpart the European Court of Human Rights (which may refer individuals to the ICC), the ICC prosecutes individuals, not nations. (According to Human Rights Watch, the United States did not join the International Criminal Court due to concerns that it might prosecute Americans for their conduct in Afghanistan.)

Categories of War Crime: Rooted in the Principles of Jus in Bello

But what makes a war crime different from an act of war? 20th-century wartime law drew its inspiration from an older philosophy when defining the war crime: in particular, the Jus in Bello principles of European Just War Theory. The Jus in Bello ("law in war") principles outline ethical principles for wartime conduct, emphasizing proportionality (i.e. no unnecessary destruction) and discrimination (i.e. no attacks on civilians) as governing principles for combatants (via Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, The Ethics Center). They also state that the destructiveness of war should be confined, the area of fighting should be limited, certain weapons should be off limits, and suffering should be minimized.

When deciding what constitutes a war crime, the Nuremberg Charter drew from this base (via Britannica). In 1945, it identified three categories of war crime: crimes against peace (or wars of aggression), war crimes (violations of the laws or customs of war), and crimes against humanity (via International Crimes Database). The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the Additional Protocols of 1977 laid out additional definitions of war crimes at length, which later formed the basis of the Rome Statute of 1998 (via Britannica).

War Crimes (Article 6): Genocide & Ethnic Cleansing

Under the Rome Statute (the governing document of the ICC), war crimes include: genocide, crimes of aggression (crimes against the peace), war crimes (grave violations of the Geneva Conventions), and crimes against humanity. These are the categories of war crimes prosecuted today at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands (via International Criminal Court).

Genocide, under Article 6 of the Rome Statute, includes any of the following acts committed with the broader intention to destroy a "national, ethnical, racial, or religious group": "killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group."

Nazi Germany and its Holocaust against the Jewish people would meet these criteria (via National World War II Museum), as would the Rwandan Genocide of the 1980s (via History).

Article 7 & Article 8: Traditional War Crimes & Crimes Against Humanity

In 2022, Axios reported that the World Health Organization verified more than 190 attacks on Ukrainian hospitals by Russian forces since late February 2022 — these attacks would fall under Article 8 of the Rome Statute, pertaining to traditional war crimes, which outlines a list of war crimes which may be prosecuted by the International Criminal Court. The destruction of Mariupol by Russian forces in early 2022 would also constitute "excessive and unnecessary destruction of property" as prohibited in this statute (via CNN).

Attacks on hospitals by American forces in Afghanistan (via The Intercept) would also qualify as war crimes under Article 8, as would the United States' treatment of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay under the prohibited act of "willfully depriving a prisoner of war of their rights or a fair trial" (via Human Rights Watch). Other war crimes that fall under Article 8 include "willfully causing great suffering," the use of expanding bullets and poison gas, the use of child soldiers, and biological experiments.

Article 7 of the Rome Statute includes a long list of crimes against humanity ranging from torture, sexual slavery, apartheid, murder, rape, and enforced sterilization to policies of "enforced disappearance of persons." Prior to the existence of the International Criminal Court, many former Nazi officials were convicted of crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials — the first international tribunal of its kind — for their actions during World War II. 12 were sentenced to death (via Britannica).

Banned Under Article 8: Crimes of Aggression (Crimes Against the Peace)

Crimes of aggression, barred under Article 8 of the Rome Statute, constitute specific acts of war that violate another nation's sovereignty without cause. Some have argued that the Russian Invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the American Invasion of Iraq of 2002 are both examples of wars of aggression (via Times Union). Additionally, the Kellogg-Brand Pact prohibits the use of war as a tool of national policy.

Jessica Laird and John Fabian Witt, authors of "Inventing the War Crime" (via Virginia Journal of International Law) explain the origins of the legal category "crimes of aggression" by discussing the horrors of World War II. "War crimes such as the execution of prisoners or the targeting of civilians were only a modest part of the horrors of the Nazi war effort," they explain. "...The heart of Allied efforts to do justice after World War II centered not on ordinary war crimes but on the claim that the Axis Powers had engaged in an unlawful form of aggressive war. To prosecute mere ordinary war crimes and to leave unaddressed the vast destruction of the Axis' aggressive use of force seemed to miss the moral heart of the matter entirely."