The Bizarre True Story Of The Comics Code Authority

In the 1950s, moral panic was rampant in the United States. At the same time as Joseph McCarthy was holding hearings and individuals with tenuous ties to communism were being blacklisted, a strange paranoia about comic books was sweeping the nation. People came to believe that comics turned children into criminals.

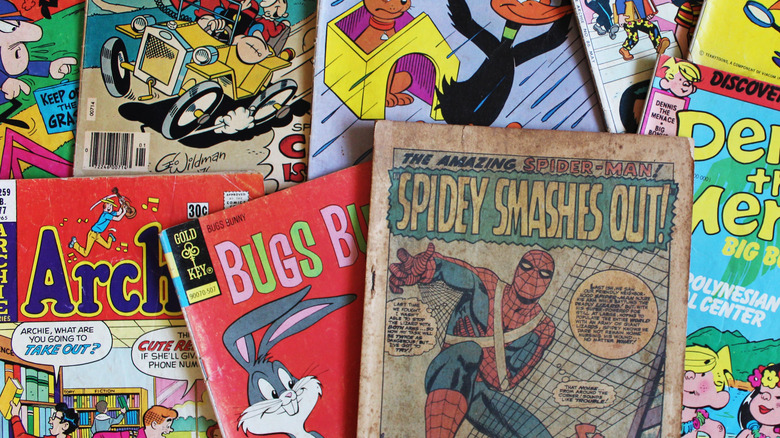

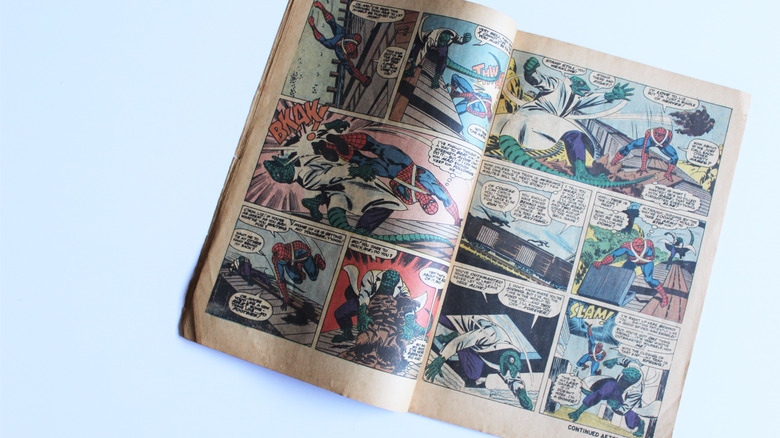

At one time in the United States, comic books were one of the most popular types of entertainment. As stated by Vox, they were enjoyed by children and adults from every background. While many think of comics as synonymous with superhero stories, there were actually many different genres of stories available. Some of the most popular were crime and horror comics, and it was these stories in particular that were targeted. As noted by Time, people came to believe that children who read violent comics became violent in real life.

An intense form of self-censorship known as the Comics Code Authority sprung up to combat the idea that comics were a corrupting influence. In order to have a comic distributed, it had to have a Comics Code seal of approval printed on the cover. In order to get that approval, comics had to follow an incredibly strict set of rules that made telling some types of stories impossible.

Comics were a cultural force

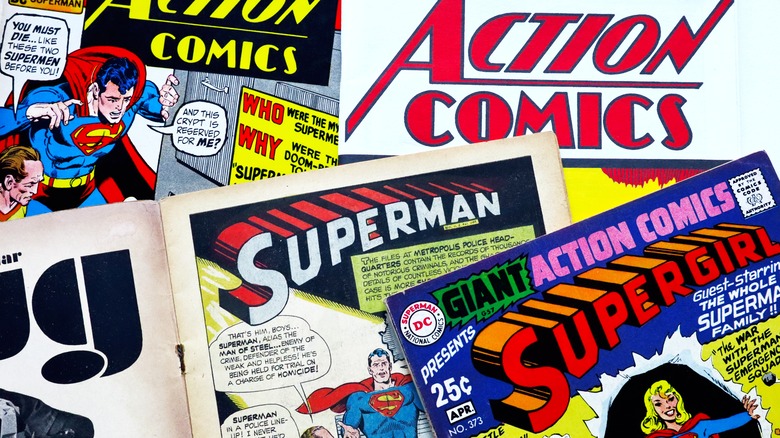

In 1938, Superman first appeared in "Action Comics" #1. This has been cited as the beginning of the Golden Age of comics. As stated by the Norman Rockwell Museum's Illustration History, at the height of its popularity in the mid-1940s, the most popular series sold approximately 1.5 million comics every month. During World War II, patriotic heroes like Captain America — who, as noted by PBS, was depicted punching Hitler in the face on the cover of the first issue — were beloved.

Some people place the close of the Golden Age at the end of the war when superhero comics were pulling in fewer readers, and some titles were even canceled. However, comics in other genres, particularly crime and horror, were increasingly popular. These were frequently darker stories that dealt with more adult themes. The late Golden Age's crime comics had fictional pulp mobsters fighting in the streets alongside actual gangsters like Lucky Luciano and Al Capone. Grinning skulls, erotically bound women, and ax-wielding murderers appeared on the covers of horror comics. Even Batman was snapping necks and leaving villains to die in burning buildings.

Comics were for everyone

At the height of their popularity, comics had no specific audience — they were pop culture, and everyone read them. They were available at newsstands and often cost only 5 or 10 cents, adding up to profits of millions for the comics industry (per Vox). As described in "The Ten-Cent Plague," those who worked on them also came from a variety of backgrounds.

The comics industry was more accessible than traditional publishing and could be created by a more diverse group of people, including Jews, Black Americans, women, and immigrants. As noted by comics creator Saladin Ahmed in BuzzFeed, while many associate the Golden Age of comics with patriotic, white, and masculine heroes saving the day in morally uncomplicated adventure stories, the comics of the time were more varied and complex. Even Superman, whose appearance marks the start of the Golden Age, was created by Jewish creators and has very often been read as an immigrant story (via The Daily Beast). There was no single type of story told by Golden Age comics, and there was a lot to choose from. In addition, there was very little editorial oversight, and creators worked against incredibly tight deadlines, leading to a wide variety of disparate styles.

A psychiatrist's controversial book condemned comics

Not everyone loved comics. In 1940, one article described comics as "sex-horror serials" that were "badly drawn, badly written and badly printed — a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems ... a violent stimulant." Comics were read by people of all ages, but the idea that they were specifically corrupting children, as the 1940 article seemed to fear, would become the core of a national panic. While some have argued that the Golden Age ended with World War II, others believe that it ended with the publication of a particular book: Fredric Wertham's "Seduction of the Innocent."

Published in 1954, Wertham's book charged comics with leading to an uptick in juvenile delinquency. As described in "Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics," Wertham was a psychiatrist who specialized in treating children. He believed reading comics, particularly violent ones that dealt with crime, to be dangerous for the well-being of children — socially, morally, and mentally. As quoted by NBC News, Wertham came to believe that "Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry."

It was based on lies and misunderstandings

Many modern critics have taken issue with Fredric Wertham's conclusion that comics were corrupting childrens' minds, but in 2012, a study of Wertham's clinical evidence by Carol L. Tilley showed that much of the clinical research that Wertham claimed to have done was either overstated or completely made up.

One major discrepancy in Wertham's book was the number of clinical subjects he was basing the work on. As noted by The New York Times, Wertham generally attributed any struggles the children he spoke to had to their reading of comic books, but often there were many other more relevant factors — such as abuse and substance abuse — in their households. Wertham claimed to have worked with thousands of children at a Harlem mental health clinic while gathering the data that he would use to write "Seduction of the Innocent," but in reality, there were likely only a few hundred being treated there. It's also believed that Wertham manipulated statements made by one child to make it seem as though many children had told him the same thing.

Wertham was also frequently misinformed about the content of the comic books he criticized. For instance, he believed that Blue Beetle was a man who transformed into an insect rather than a superhero who happens to be named after one. Famously, he believed that Batman and his sidekick Robin were in a romantic relationship.

There were comic book burnings

Fredric Wertham advocated for making it illegal to sell any comic book to people under 15 years old and a ratings system so that it would be obvious if there was violence, sexual content, or gore in the comic (via Slate). While his plans for the comic industry were extremely strict, he never recommended that comics be destroyed altogether — but others did.

The anti-comics movement was a massive national moral panic, with comic books becoming a scapegoat for all types of social issues. While Wertham's incitement of comic books made the anti-comics sentiment more mainstream and is credited with ending the Golden Age of comics, there had already been comic book burnings before "Seduction of the Innocent" was even released. As shown by Tor, between 1945 and 1955, there were 16 mass burnings in which thousands of issues of comics were collected and set on fire.

There were Senate hearings

Fredric Wertham may have been driven to blame comics by personal motivations, but there genuinely was a significant rise in juvenile delinquency in the 1950s. As noted by the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, Congress investigated the possibility that young people reading horror and crime comics could be the cause. It is believed that Senator Carey Estes Kefauver, who oversaw the hearings, was actually interested in going after the mob rather than the possible corrupting influence of comics. At the time, organized crime had connections to all magazine and comic book distributors. As detailed by Vox, the U.S. government never took any action against the comics industry after the hearings, but the damage was already done — these hearings were publicly televised and changed the public's perception of comic books.

Soon after, 15 comic book publishers shut down. EC Comics, a publisher of many of the most popular horror and crime comics, canceled all of their publications except the famous humor magazine Mad. It was evident that the comics industry was in danger of shutting down completely unless the publishers took serious action.

The code was an attempt to save the comic industry

While the comics code is often credited with destroying comics, it was implemented by the publishers to try to save them. There was a fear that if they didn't seem to be making major changes and self-censoring, the government would shut them down. As explained by Time, the publishers came up with a strict set of rules that every comic would have to adhere to — the "Comics Code."

Several representatives from comic book publishers (including EC) along with representatives from two major distributors got together to come up with a set of standards for what could be printed in a comic. As detailed in "The Ten-Cent Plague," they based the moral standards on those enforced on Hollywood by the Hays Code. Before a comic was published, it was supposed to be sent to them for approval. They would either approve it or suggest changes that would allow the story to conform to their code. It wasn't technically a mandatory legal process, but printers, distributors, and retailers feared releasing comics without the Comics Code seal of approval on the cover would lead to protests of their business. It was almost impossible to get around the Comics Code if a publisher wanted their comics to be sold.

Some words and themes were banned

In order to get the Comics Code seal of approval on the cover of a comic, the publishers had to ensure it followed the rules. Some were subjective, but there were some words and themes that would always get a comic rejected. Many of these specifically targeted the horror comics, which the anti-comics movements had particularly objected to. As stated by Time, no comic with a title containing the words "horror" or "terror" could be approved by the Comics Code. Specific bans on many common horror themes made it difficult for any horror comic to get through, even if it didn't have horror in the name. The stories couldn't feature most monsters — including werewolves, vampires, zombies, or ghouls — and cannibalism and torture were also banned.

Other parts targeted the equally controversial crime comics. As stated by History, comics could not depict any crime taking place unless the criminals were using magic or science fiction technology. There could be no reference to drug use, and swearing was completely banned. Even slang was generally not allowed, though a small amount could be allowed if it was vital to the plot of the story.

There were moral rules

Some of the rules of the Comics Code were not as simple as banning a particular word. As detailed in "The Ten-Cent Plague," many of the rules attempted to ensure that the stories that comics told were moral. These could be subjective, and it was hard to know exactly what would get approved. As explained by History, there was no way to appeal something that was rejected.

One of the areas that the Comics Code took aim at was sexuality. Along with nudity, drawing women in a way that the Comics Code Authority deemed sexualized was forbidden (via Time). Per History, romance stories were allowed, but they were required to "emphasize the value of home and the sanctity of marriage." The stories could include divorce, but they could never be depicted as positive. Sexual perversion was also not allowed, but what exactly fell into that category depended on what administrator for the Comics Code Authority happened to be working that day.

Authorities, like police, judges, or politicians had to be depicted as intelligent and effective, and while crime could still make up an element of the plot of a comic book, criminals couldn't be sympathetic.

Stories were forced to change

Since it was extremely difficult to get a comic book that didn't have the Comics Code seal printed, distributed, and sold, publishers and creators were forced to change stories that didn't meet the standards of the code.

As described by History, prior to the Comics Code, there were storylines in comic books that challenged social conventions about sexuality and gender. For instance, "Space Adventures #3," released in 1953, depicted a scientist who had gender-confirming surgery. The code's rules about how romance and sex could be depicted made it impossible for creators to include LGBTQ+ characters. The code also prohibited any depiction of prejudice based on race or religion, but as noted by Vox, this generally led to rejecting stories that depicted characters that weren't white altogether.

Even storylines that were not particularly transgressive or challenging to the status quo often had to be changed. Since Fredric Wertham claimed that Batman was gay, the publisher (DC Comics) was eager to depict Batman in a relationship with a woman. In the past, Batman and Catwoman had romantic tension. But by the rules of the Comics Code, Batman could not have a romantic relationship with a criminal, so they were forced to remove Catwoman and create Batwoman, who was considered a more morally acceptable woman for Batman to be interested in. (In modern comics, Batwoman is depicted as a lesbian — though in 2013, the writers of "Batwoman" stated that they were also facing censorship.)

Some creators worked around the code

While many stories were forced to change to meet the strict rules of the Comics Code, some creators were able to slip subversive content into their work. Over time, the power that the Comics Code eroded, and eventually, it was possible for publishers to release comics that bent the rules.

As described by Vox, creators like Jack Kirby were able to include social commentary in their stories in a way that would still allow their publishers to get the seal of approval from the Comics Code. In 1971, the Nixon administration contacted Stan Lee at Marvel, requesting that they have an issue of a popular comic with an anti-drug message — but the Comics Code Authority rejected the idea, interpreting their guidelines as forbidding all references to drug use. Lee ran the storyline in "The Amazing Spider-Man" anyway and simply had the Comics Code seal removed for those issues, with the understanding that he would return to following their guidelines after those issues were concluded. As noted at CBR, after it was released, the public reaction was confused — it seemed bizarre to people that the code would forbid a comic with an anti-drug message. More anti-drug comics followed, and the code changed as a result of the public and media backlash.

The industry changed forever

The public's panic over comic books died down gradually. Comics were not as popular as they were in the Golden Age, and they were no longer available for purchase everywhere. In the '70s, exclusive comic book shops became more common. Having a seal of approval from the Comics Code became less important as publishers relied on their old distributors less. Over time, the code was relaxed, and there was no public outrage over it. As noted by Time, in 1971, monsters such as vampires and werewolves were allowed back in comics. Drugs were also allowed to be included as long as they were necessary and made sense in the plot. As stated by Vox, soon after, comics creators were able to make interesting villains with complex backstories, even if they seemed sympathetic to audiences.

In 2001, Marvel stopped bothering to get the Comic Code's approval on their comics altogether. In 2011, DC and Archie Comics did the same. Without any publishers displaying their seal of approval on the covers of comics, the code was essentially over. Most publishers replaced the code's guidelines with a rating system similar to TV and film that allows customers to make informed decisions about the content they're going to read without preventing those stories from being told.