Three Saints So Far Were Born In The United States

Christianity has been a thing for about 2,000 years, give or take, and in that time, about 10,000 people have been recognized with the title of "saint," according to Britannica (and note that here we're referring only to people deemed saints by the Catholic Church, and leaving out saints of other faiths, such as the Eastern Orthodox Church). As The Conversation reports, the church applies the title to someone who exemplified a life of "heroic virtue."

Although Christianity has been a thing for two millennia, the United States of America has only been a thing for a bit over an eighth of that, at about 250 years. Similarly, the landmass that would ultimately become the U.S. has only had Christians on its soil for 400 years, give or take. The overwhelming majority of people deemed saints by the Catholic Church (per Catholic Online) have been from elsewhere — Europe, Asia, Africa, and so on. In 400 years of American history, only three people who were born in the U.S. — all of them women — have been declared saints so far.

What makes a saint?

The process of becoming a saint is remarkably straightforward and above-board, and the rules are written down and available for anyone who wants to take a look. A simple explanation, provided by BBC News, goes like this: First of all, no one can even be considered for sainthood until five years have passed since their death. However, even that rule can be waived, and has been at least twice, once for Pope John Paul II, whose waiting period was waived by his successor, Pope Benedict XVI, and earlier for Mother Teresa, whose waiting period was waived by Pope (now Saint) John Paul II.

After the customary waiting period, the bishop of the diocese where the candidate died will launch an investigation into the person's life, looking at their piety, their virtue, their works, and so on. If that person is accepted for consideration for sainthood, they're deemed a "Servant of God." Following that, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints will look even more deeply, and pray about it, and if the candidate passes muster, the case is sent to the pope, who may deem them "venerable." Then, Vatican experts will look for evidence of miracles, and if any is found, the candidate will be publicly declared "beatified" and given the title "Blessed." From there, it will go to the sitting pope, who, if he deems the person a saint, they are "canonized," also in a public ceremony. The steps and proofs can be bypassed in the case of someone who is ascertained to have suffered martyrdom — to have been killed because of their religious faith.

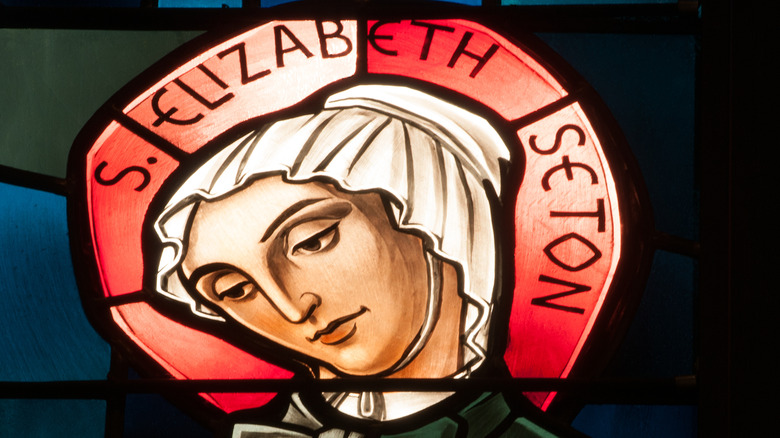

Elizabeth Ann Seton is credited with posthumous miracles

The first canonized individual born in the United States was Elizabeth Ann (Bayley) Seton, born in New York in 1774 to wealthy, not-Catholic parents (they were, like most wealthy American settlers, Episcopal, according to Time). She married a non-Catholic in 1794, and her wedding was called the "social event of the season" by society writers of the time.

However, after her husband died and she was left destitute, she converted to Catholicism. She later was instrumental in the establishment of a Catholic school as well as a religious order for Catholic women. However, it was activities attributed to her after her 1821 death that earned her the title of saint. Specifically, according to a companion Time report, her intercession resulted in a nun being cured of pancreatic cancer, a young girl being cured of leukemia, and a construction worker being cured of "a complicated viral affliction of the brain." Time notes that normally four miracles are required for sainthood, but the pope at that time, St. Paul VI, waived that requirement when he canonized her (per Catholic Online) in 1975.

Katharine Drexel gave the church all the money

Like her predecessor in being canonized, Katharine Drexel was born into wealth, according to Catholic Online, on November 26, 1858. Unlike St. Elizabeth Seton, Drexel was born Catholic. The family was blessed financially and spiritually, and her mother and father (a Philadelphia banking magnate) exemplified the Christian life, helping out the poor who came to them, and themselves going to women who were too afraid to seek them out in order to offer assistance.

When she was in her 20s, according to a Time report, Katharine renounced her wealth and social status and instead threw herself into religion. She used her considerable inheritance — $7.5 million — to minister to Native Americans and Blacks, two groups whose mistreatment and marginalization she witnessed firsthand. "The feast of St. Joseph brought me the grace to give the remainder of my life" to these communities, she said.

According to Britannica, St. Katharine is credited with two miracles: restoring the hearing of a deafened young boy and that of a young girl, who purportedly got her hearing back after her ear was touched by some of St. Katharine's possessions. Katharine Drexel was canonized by the reigning pope, St. John Paul II, on October 1, 2000.

Kateri Tekakwitha

In terms of individuals born in the United States, the last individual to be canonized so far by the Catholic Church was born a century before St. Elizabeth Seton, back before the United States of America existed. Kateri Tekakwitha (one of many variant spellings) was born 1656, her father a Mohawk and her mother an Algonquin who had been captured by the Mohawks and given as a wife to her father, according to Catholic Online. The only Native American to have been named a saint so far, according to Time, she became a Catholic when her father converted to Catholicism. Having survived smallpox as a young girl, after she refused marriage her tribe began to persecute her, and she fled to what is now Montreal.

Tekakwitha, who prayed steadfastly for the conversion of Native Americans, went to great lengths to live according to her devotion, including personal penances such as placing thorns on her sleeping mat, or by giving her food an unappetizing flavor (when she ate, that is; she often fasted for long periods of time). According to the Seattle Times, Pope Benedict XVI credited her with curing a boy of a deadly, flesh-eating bacterial infection in 2006. She was canonized by Pope Benedict on October 21, 2012. Her patronages include environmental stewardship, people in exile, and Native Americans.