The Untold Truth Of George Washington

There is no one bigger in the newly-minted annals of American mythology than the father of all Founding Fathers, George Washington. As both the first president of the United States of America and the man who spearheaded the charge to free the colonies from oppressive British rule, he was exactly what America needed, right when they needed it. While many historical figures don't stand the test of time, Washington still holds a special place in American history.

As with any figure that begins to straddle the line between myth and reality, there are always going to be some facts that fall by the wayside and legends that spring up unchallenged. This can lead to something of a muddling of who the person actually is, and while Washington is fairly well understood, there are facts about him that help to fill in who he was as a human being, and as a leader. Here is the untold truth of George Washington.

George Washington had very little formal education

In the modern-day, success and education often go hand-in-hand. Many companies require diplomas before they even consider an otherwise worthy candidate for a job. And the greater the power being sought, the more education is expected. You will not likely find a politician without an accompanying degree; often they hold a rather lofty one, from a rather lofty institution of learning.

It wasn't always that way. Washington himself had a bit of a complicated relationship with formal education. For starters, he didn't have much of one at all, according to his estate. When his father passed away, the Washingtons had very little funding, and could no longer afford to send 11-year-old George to school. Everything else that Washington learned was informally or self-taught. When he was a teenager, he wrote out his own copy of the "110 Rules of Civility," which guided his actions in the presence of "pleasant company," according to the Washington Papers. Such rules included the very wise "Think before you speak."

Furthermore, Washington was taught math and the science of surveying by his friends, the Fairfax family. This all contributed to the hodgepodge education that the future first president built for himself.

He was raised by a single mother

Mary Ball Washington, the mother of George Washington, is a polarizing figure. When George was only 11, his father died, leaving Mary to raise five children all on her own. According to History, she has been described in both positive and negative terms, yet throughout is defined as what she really was — strong and resilient, the mother who raised five exceptional children. She also defied the gender norms of her time, refusing either to remarry or give up the family's property.

That said, she was certainly a stern mother, who required the help of her sons to run the farm. This was all something Mary herself had learned growing up with her own mother, who herself was left single after her husband's death.

While historians have often been hard on her toughness as a mother, this was the standard of the time, according to Martha Saxon's book "The Widow Washington." She writes (via History), "The fond mother, the mother who is psychologically and emotionally utterly available and has nothing but unconditional love for her children came about in the late 19th century," over 150 years after Mary was raising George.

George Washington fell in love with a married woman

When George Washington was still an awkward 16-year-old, he accompanied his half-brother Lawrence around the high-class circles of Virginia. One particular place George often accompanied him to was Belvoir, the Fairfax estate on the Potomac, and that's where George met the 18-year-old Sally Fairfax.

According to the estate at Mount Vernon, Fairfax had a massive part to play in the molding of young Washington. She taught him how to dance, how to charm others, a greater understanding of history and philosophy, and much more. Years later, during the French and Indian War and while engaged to Martha, Washington confessed his love to Fairfax. His words (via his estate): "the world has no business to know the object of my love, declared in this manner to — you, when I want to conceal it." Yet, through it all, Fairfax remained close friends with both Washington and his wife, Martha.

Hard times fell on the Loyalist Fairfax estate and Sally retired to England. Washington wrote to her one last time, in 1798, begging her to come back: "eradicate from my mind the recollection of those happy moments, the happiest in my life, which I have enjoyed in your company." She died alone 13 years later, her feelings towards Washington never known, and likely lost to time.

He sparked a global war

So much of George Washington's lasting legacy is built around his military prowess during the American Revolution, but he wasn't always a sparkling general. That took some learning, and it took some failing, and no failure was as big as when he practically single-handedly sparked a world war, according to History.

During the French and Indian War, the British and French vied over who would control the fertile lands of the central United States, ignoring, as they too often did, that the Native population was already there. The 22-year-old Washington, never having seen combat before, joined with Tanacharison, leader of the Mingo tribe. Tanacharison was a veteran warrior with decades of experience on the battlefield, but that didn't stop Washington from instigating what would become the Seven Years' War. Tanacharison, eager to win his own battles against rival tribes in the area, didn't exactly stop Washington from attacking a French fort and killing French officer Joseph Coulon de Jumonville.

The French were less than pleased. According to Colin Gordon Calloway, author of "The Indian World of George Washington: The First President, the First Americans, and the Birth of the Nation," the fault rests in Washington. "I frankly see a young man seeing his first command unraveling before his eyes. This was a disaster, and I think very quickly thereafter, he's kind of trying to cover it up," Calloway says (via History).

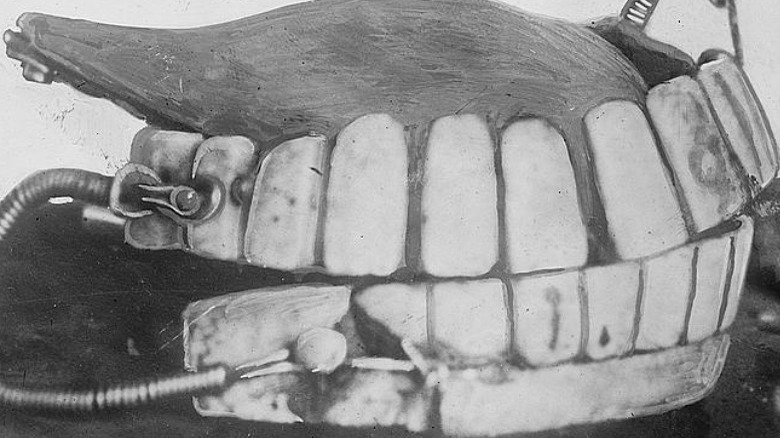

George Washington's teeth weren't made of wood

For as much truth about George Washington that gets overlooked, there are also a fair share of myths and legends. One such myth, odd as it may sound, is centered on the composition of his teeth, as well as the accompanying dental practices that led to his supposed wooden "chompers."

According to the estate at Mount Vernon, in 1755, the 23-year-old Washington made dental care a top priority in his life. He invested in various methods of dental hygiene, such as toothbrushes, tinctures, and toothpaste. Yet he couldn't stop his suffering from severe toothaches, leading to multiple extractions over several years of his early adult life. For the next decade and beyond, he would continue to write about his dental problems, while using false teeth to fill the gaps left by his real ones. Portraits showed scars from an abscessed tooth, and poor Washington was just having an awful time keeping his teeth intact. By 1789, he had only one tooth left in his mouth.

As for the question of what his fake teeth were made of, historical records reveal that there were no wooden teeth in his dentures. In fact, according to Live Science, he had multiple sets made of all sorts of materials, including ivory and metal.

He utilized the first-ever American spy organization

While George Washington will be remembered for his military prowess first and foremost, it was another move during the Revolutionary War that may well have turned the tides in the rebel army's favor — the creation of the Culper Spy Ring, America's first intelligence organization. Using the Culper spy ring, Washington was able to collect first-hand intelligence on British military maneuvers, as well as sniff out the treachery of Benedict Arnold before it could lead to any particularly nasty results for the Revolutionary cause.

It all began when the British occupied New York in 1776. General Washington desperately needed intelligence on British movements in the city, but there was no reliable source that could provide it, according to History. A solution presented itself in 1778, when Benjamin Tallmadge and a group of Long Island friends formed the Culper Spy Ring. Using only those he knew he could trust, Tallmadge gathered information that he would pass on to fellow spy Caleb Brewster, who would then take the reports to General Washington himself.

Washington relied on the information from the Culper Spy Ring to plan his next moves. Thanks to their reports, the Revolutionary army was able to thwart an ambush on the assisting French army, as well as catch and execute British chief intelligence officer John Andre.

George Washington never chopped down a cherry tree

There is a story about George Washington that has been told so often that many people just accept it to be true. Supposedly, young George Washington received a hatchet on his 6th birthday and promptly took it to his father's cherry tree. When confronted by his father, Washington admitted to his misdeed, saying, "I cannot tell a lie ... I did cut it with my hatchet." This all comes from Mason Locke Weems' arduously titled book, "The Life of Washington the Great: Enriched with a Number of Very Curious Anecdotes, Perfectly in Character, and Equally Honorable to Himself, and Exemplary to his Young Countrymen."

But none of that actually happened. While Weems published the book in 1800, the year after Washington's death, his motivation was two-part. First, he wanted to spread stories of the greatness of Washington. Second, he wanted to sell a book. According to Washington's estate, after the former president's death in 1799, there was a great deal of interest in learning about him, and Weems was ready to meet the demand. He openly admitted as such to a publisher in January 1800, explaining, "Washington you know is gone! Millions are gaping to read something about him ... My plan! I give his history, sufficiently minute ... I then go on to show that his unparalleled rise and elevation were due to his Great Virtues."

Weems saw an opportunity, and he took it. Although, funny enough, the cherry tree story didn't even appear until the fifth printing of the book, in 1806.

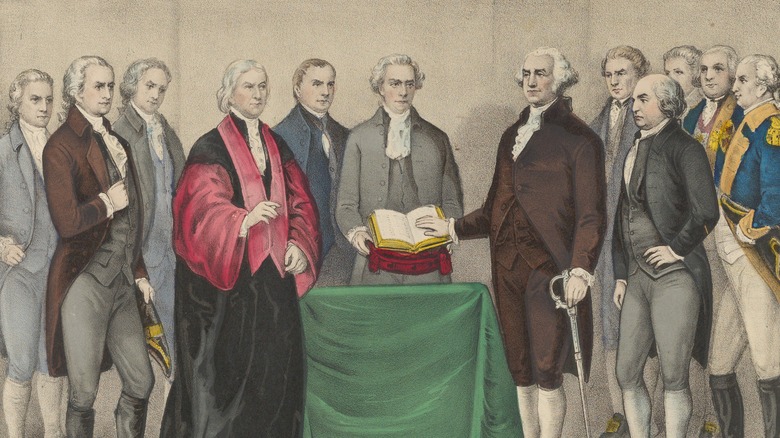

He was a reluctant leader

One might expect that there was a good deal of rejoicing when George Washington won the first presidential election of the newly-minted United States of America, but that assumption would be wrong. In fact, George Washington had a much different thought on the matter. He told his future Secretary of War, Henry Knox (via Smithsonian), "movements to the chair of government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution."

So, essentially, Washington felt akin to a criminal condemned to death after he had unanimously won the election as president, and his lamenting continued in his own diary on the way to take office: "About 10 o'clock, I bade adieu to Mount Vernon, to private life, and to domestic felicity and, with a mind oppressed with more anxious and painful sensations than I have words to express, set out for New York ... with the best dispositions to render service to my country in obedience to its call, but with less hope of answering its expectations."

Here was the man who had built the foundation of the nation, was elected to continue to shape it, and yet wanted nothing to do with it. He wanted a private, happy life, but his pesky colleagues refused to let him have it. He was too good a leader, after all. Thankfully, he was willing enough to hear the country's call.

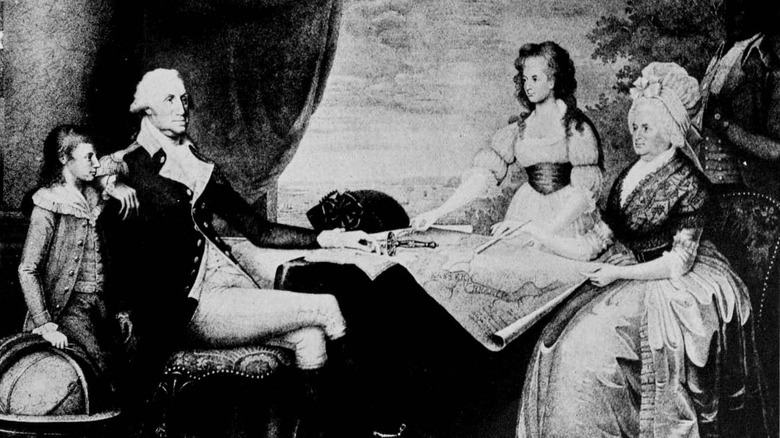

George Washington never had kids

Given the overwhelming mythology attached to George Washington, it might seem inevitable that he would have bred a large family full of inspiring young spawns, ready to bring forth the next generation of American "excellence." Yet Washington had no kids of his own, though he never really had to. He was the "father" of an entire nation, after all, not to mention becoming stepfather to his wife Martha's children. According to Mount Vernon, Martha brought two children from her previous marriage, and George became a father to them, as well as a grandfather to the four grandchildren that they produced. John Parke Custis, the oldest of Martha's two children, reportedly caused Washington much grief as a teenager, according to Washington's estate.

Unfortunately for Martha, her children did not outlive her. She had an additional two older children, neither of whom lived to call the future president their stepfather, and the two children she did bring to the new marriage both died before Washington himself, leaving Martha and George to serve as stand-in parents yet again for their four grandchildren.

Their grandchildren, however, would live fruitful lives beyond the life of their grandparents. It was their only grandson, George Washington Parke Custis who, according to Mount Vernon, helped conserve the legacy of his grandfather.

He really loved dogs

Dogs are almost universally loved, and George Washington was no exception. He didn't just love to have the occasional dog around the house, though — he kept a veritable pack at Mount Vernon, diversifying his breeds to cover nearly every available canine.

According to his estate, Washington had practically every kind of dog imaginable, from every major group. This included dalmatians, greyhounds, Newfoundlands, and more. They found like they were quite spoiled and indulged for the time, too. They "were provided with shelter and fresh water from a spring running through a kennel, which was located about 100 yards south of the original family tomb. The General personally inspected the kennel each morning and evening and took time to visit with his dogs," according to Mount Vernon.

Then there was the manner of naming them, something that Washington took special pride in. He had hounds named Sweetlips, Vulcan, Ragman, and more; a dalmatian named Madame Moose; a Newfoundland named Durmer. In one story shared by his estate, Vulcan the hound stole an entire ham that was to be served at dinner, which Washington found hilarious — his wife, however, did not.

George Washington's opinion of slavery changed

There's no hiding the fact that George Washington was an enslaver. On his deathbed, he did something that no other founding father did — in his 29-page will, he drew up a plan for all those who were considered his property, intending to free each and every one of them. He also added a clause to provide his valet a $30 annual pension and set up a permanent fund to provide clothing and food to the elderly freedmen.

Richard Allen, a free man, delivered a powerful eulogy on Washington's behalf, saying (via Mount Vernon), "He has watched over us, and viewed our degraded and afflicted state with compassion and pity — his heart was not insensible to our sufferings." He would also go on to say, "Unbiased by the popular opinion of the state in which is the memorable Mount Vernon, he dared to do his duty, and wipe off the only stain with which man could ever reproach him."

While the intent was admirable (if extremely last-minute), the follow-through hit a few kinks. Namely, only 123 of the 317 enslaved persons he listed were enslaved by Washington himself — most were technically part of his wife Martha's estate, and they were therefore inherited by the grandchildren, meaning neither George nor Martha had any authority to free them.

He grew fed up with politics

Not surprisingly, there were many who wanted George Washington to run for a third term as president of the United States — which he absolutely refused to do. The reasoning behind his decision was well-documented, and it showcases just how sick he was of the political scene in America, even at such an early stage in the nation's history. On the one hand, he just wanted the retirement that he had been so cruelly denied by being elected in the first place. But his distaste for a third term goes deeper than that. According to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, "There was his promise not to seek unfair power as a government official."

Then there was the matter of the sheer state of politics in the United States. As the Gilder Lehrman Institute points out, Washington wanted to safeguard the potential that any one man would try to subvert the power of government for themselves.

Over time, his words got more venomous on the subject of politics. Washington, writing about the Democratic Party, noted, "Let that party set up a broomstick, and call it a true son of Liberty, a Democrat, or give it any other epithet that will suit their purpose, and it will command their votes in toto!"

George Washington's death was perplexing

George Washington was perfectly healthy one day. And then, he just wasn't. The story goes, according to the National Constitution Center, that just days earlier, the former president was feeling fine when he went riding around his estate. But the weather was bad that day and he got completely soaked, and then made the decision to stay in his wet clothes through dinnertime.

This led to him waking in the night, unable to properly breathe. That's when the doctors were called. They "bled him four more times over the next 8 hours, with a total blood loss of 40%. Washington also gargled with a mixture of molasses, vinegar, and butter; he inhaled a steam of vinegar and hot water; and his throat also was swabbed with a salve and a preparation of dried beetles."

It all failed. According to doctors of the time, he died of "cynanche trachealis, also known as the croup, an inflammation of the glottis, larynx, or upper part of the trachea" (via the National Constitution Center). More theories came out over time — diphtheria or "septic sore throat, probably of streptococcic origin, associated with acute edema of the larynx." While not everyone agrees, the modern consensus is that it was acute bacterial epiglottitis. Whatever the case, it troubled Washington not — his last words, according to his estate, were rather peacefully, "Tis well!"