Strange Things Found In Medieval Manuscripts

Centuries ago, books were almost wiped out entirely with the fall of the Roman Empire at the hands of barbarians, according to Britannica. Seeking to safeguard the future of the written word, monasteries became the central hub for ink and paper. Libraries blossomed in convents and monasteries, and monks passed the time by writing and copying new books to bolster those libraries.

You'd think, perhaps, that putting the clergy in charge of being scribes and of the safekeeping of books would lead to some one-dimensional manuscripts, but you'd be wrong. Especially when it comes to the margins of those books. While the books themselves had pretty expected commodities — words, for instance — the marginalia was anything but expected. They are the kinds of doodles you'd expect from middle schoolers scribbling in their notebooks, only the quality of these medieval images is a bit higher and oftentimes oddly specific.

Although it's not just in the margins that strangeness is found — sometimes it's right in the middle of the page, the featured presentation, and sometimes it was never meant to be there at all. Here are some of the strangest things found in medieval manuscripts, in the margins or otherwise.

Knights fighting snails

Knights were something like celebrities during the middle ages. They were the rich, landed gentry, the warrior class, and the overseers of protection, all rolled into one. So needless to say they fought a great many things, from rival knights, to villains, to dragons and monsters. But apparently, they had another common foe as well — a foe that most probably wouldn't imagine a knight fighting. Throughout the margins of 13th- and 14th-century manuscripts, knights can be found engaged in combat against snails of all types and sizes. Sometimes they are jousting snails, other times wielding sword and shield, sometimes fleeing across the page.

Medievalists at the British Library highlight just how typical this marginalia is, and posit some theories as to why it's so prevalent on the page. One leading theory is that it depicts the struggle of the poor and their fight against the aristocracy. Other theories include the representation of the "saucy sexuality" of women, the resurrection of Christ, the annoyance of garden snails, or the inevitability of death (via TED-Ed).

Meanwhile, Lillian Randall proposed a political theory in her article "The Snail in Gothic Marginal Warfare." According to Randall, the snail represented the Lombards, a group widely despised at the time for various unsavory characteristics. An example: a report in the 13th century criticizes them for such grievances as "failing to wash their hands before meals and of boorishness for speaking out of turn."

Killer bunnies

Whether they were wielding axes, bows and arrows, swords, or lances, the bunnies found in medieval marginalia are ready for battle, and they look really happy to be ready for battle too — like they've been waiting all their life to chop off some heads. You'll see them engaged in all sorts of awful crimes and cruelties like decapitating bound humans and hanging dogs from trees. It's really a what's what of cruel and unusual death by rabbits.

As with just about all marginalia, there's a reason why these rabbits are up to un-rabbit-like shenanigans, and it isn't just an arbitrary choice. According to Daily Art, rabbits during the middle ages were seen as symbols of purity and helplessness, which is why medieval marginalia artists turned them into sadistic, cruel killers. This world in the margins was meant to be a sort of inverse world to what people would be used to.

Naturally, it's impossible not to think of the killer rabbit scene of "Monty Python and the Holy Grail" fame. Go figure that there was quite a bit of medieval lore buried in the depths of the comedy troupe.

Butt trumpets

Invoking similarities to the cartoonish intermissions found in "Monthy Python and the Holy Grail," the butt trumpet was not an original concept. In fact, it was so grounded in medieval manuscript marginalia that it was essentially the middle ages equivalent of a fart joke. Keep in mind that monks were the ones drawing these gems in the margins. The general public would have been illiterate, and thus unable to read the words on the page, but everyone speaks the language of images, including images of people playing brass instruments with the wrong end.

There are interpretations of what this particular illustration meant, from TED-Ed. Some think that it's a political smear, or a sign of disapproval centered on what was happening in the text across from the butt trumpeter, but the overwhelming thought is just that it was exactly as advertised — a human being playing the trumpet with their butt. It was meant to be funny and, by most accounts, it was.

It didn't just have to be the trumpet either. This level of absurdism can best be seen in mass in the famous "Garden of Earthly Delights" painting by Hieronymous Bosch, which happens to use the flute in this way (via The Guardian).

Book curses

Making books in the middle ages was a lot different than now. Nowadays, millions of books are printed any given year, but back then, it was a job to build a book. A single book could take years for one monk to write, according to Atlas Obscura, with the fanciful letters, the detailed illuminations, and the cartoonish marginalia. Atlas Obscura quotes one medieval scribe who spoke poorly of the process: "It extinguishes the light from the eyes, it bends the back, it crushes the viscera and the ribs, it brings forth pain to the kidneys, and weariness to the whole body."

Given the sheer time and labor commitment, it's understandable that the scribes would be protective of their work, writing curses in the front and back of books. Two examples, both from Marc Drogin's book "Anathema! Medieval Scribes and the History of Book Curses" (via Atlas Obscura), give a feel for what book thieves could be facing. One curse, short, sweet, and rhyming, went like this: "May the sword of anathema slay, If anyone steals this book away." Another curse: "If anyone take away this book, let him die the death; let him be fried in a pan; let the falling sickness and fever size him; let him be broken on the wheel, and hanged. Amen."

Conveniently for the scribes, this was at a time when people believed in such curses, meaning that as long as they could read, they would have been deterred.

Really weird elephants

Most everything in medieval marginalia is pretty easy to identify. Even if it's someone playing the trumpet with their butt or a rabbit about to decapitate a naked man. But if you were to see the bulky grey creatures with a massive trunk for a nose and a castle on its back, you may take a little longer to confirm that it was, in fact, an elephant.

They look kind of like an elephant, close enough for positive identification, but they don't look all the way there. Like something is a bit off. The thing about elephants is that most people in the middle ages had never actually seen one, according to The Collector, so when they came to draw them, they got the general idea across and neglected details that known well today — like the fact that elephants have knees.

According to Getty, the elephant was more of a fantastical beast than a natural one. Since most medieval residents were just as likely to see a unicorn or dragon as an elephant, the artist had to take a little creative license, and that's why there are so many variables in the renderings of elephants in the margins.

Fantastic beasts

Seeing as how the margins were where the scribe could doodle whatever was on their mind, it makes sense that there were some less recognizable creatures waddling and flying along the creases, ones that won't be found in any natural history books. Fans of the Wizarding World, however, may well be able to identify a lot of said creatures, even if they look a little different than they appeared on the big screen.

Margins boasted the likes of basilisks, centaurs, unicorns, dragons, phoenixes, merpeople, and more, per the British Library — all creatures that most today accept do not exist except for where they can be found in storybooks.

At the time, though, people wouldn't have been able to say definitively whether they existed or not. Similar to how the elephant was just a rumor to most, so too were the dragon and the unicorn. In fact, many may well have believed more in the unicorn — given the presence of narwhal horns posing as unicorn horns (via The Met) — than in elephants, which had less representation in Europe.

Animal musicians

Music has a big presence in the marginalia of medieval manuscripts, much like traditional scenes of violence such as jousting and sword battles. This left room for scribes to bring out a little bit of their creativity in both regards. You'll find cats jousting on snails with human heads, and you'll find lions playing the violins.

In fact, there are quite a few animals playing musical instruments, as seen at Classic FM — rabbits play organs, monkeys play bagpipes, donkeys play the lute; it's all there, a regular animal symphony. These types of illustrations were most often found in specific books called Psalters, which were written depictions of psalms. Given the musical nature and rhythm of psalms, the accompaniment of animals playing a tune isn't that surprising, since both Christians and pagans had so much animal representation in their culture.

According to HAL Open Science, it also ties deeper into the practice of "adynata," from Greek, and "impossibilia," from Latin; both of which refer to the old tradition of depicting that which is impossible. It's a practice that carried on into medieval tradition, particularly when satirizing politics or the church.

Human-monster hybrids

They call the middle ages the "dark ages" for a reason, and most of it is steeped in the fact that science and medicine were just plain backward at the time. Not to mention the general lack of knowledge about what was real and what wasn't. That includes the possible existence of fantastic beasts, as well as what humans were capable of producing when coupling with beasts.

Consider the legend of the pig-faced woman that tracked across Europe for about three centuries, starting in the 1630s, according to Owlcation. It lasted well into the 19th century, too; people actually believed there was a woman wandering about with the head of a pig and the body of a human.

Scale that back another few centuries, and the belief and subsequent fear in hybrids was even more widespread. According to BBC, the very idea of mixing a human with a beast, a la the manticore, was a terrifying concept to the medieval mind. Never mind the belief that animals don't have souls and humans do. Nonetheless, The British Library houses tons of examples of marginalia depicting the unholy combination of human and beast, for those that are curious.

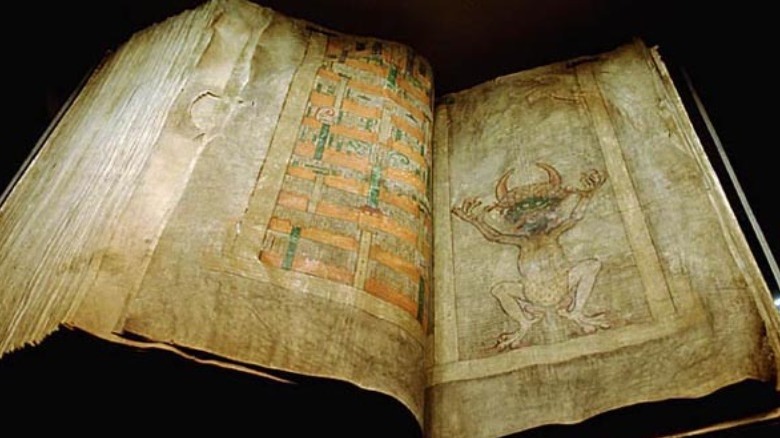

The Devil himself

While most of the curious things found here are in the margins, this one is the book itself — a massive, three-foot-tall book totaling 620 pages. Amazingly, according to Atlas Obscura, it was all compiled by a single, anonymous monk in Bohemia. It's known as both the Devil's Bible and the Codex Giga, the latter of which literally means 'giant book'. It would have taken this singular monk 20 to 30 years to finish this mammoth undertaking, but the result speaks for itself. One page, in particular, stands out against all the rest — a full-page depiction of the devil, illuminated in beautiful full color.

As to why that's so curious, the answer is simple — no one really knows why it's there. The book itself contains the Old and New Testaments, as well as texts addressing the calendar, medicinal matters, exorcisms, grammar, and more, but the devil himself stands alone, unaccompanied by any text or explanation.

There are legends surrounding the manuscript, of course, one of which gives the scribe a name — Herman the Recluse. According to the legend, presented by All That Is Interesting, Herman was walled up and sentenced to death, given the impossible task of writing a book detailing all human knowledge. Knowing this to be impossible, Herman called on the help of the devil to complete it.

Cat prints

Considering just how long it took to write an entire manuscript, as well as how labor-intensive it was, it's more than understandable that the scribes would have been incredibly protective of their work, ensuring that nothing went wrong. No smudges or spills or stains, lest they spoil years of previous work.

Which is why it's so funny to see a medieval manuscript with inky cat prints tracking across the middle of the page, via Smithsonian Magazine. Emir Filipovic was the one to discover the feline contribution, and his assessment of the situation is spot-on: "The photo of the cat paw prints represents one such situation which forces the historian to take his eyes from the text for a moment, to pause and to recreate in his mind the incident when a cat, presumably owned by the scribe, pounced first on the ink container and then on the book, branding it for the ensuing centuries."

It's a situation that would be so understandable to the modern reader. Cats getting in the way of writing, clambering across laptop keyboards, spilling water over handwritten pages. Only for this poor medieval scribe, there was no delete key, meaning that his cat companion's footfalls are just as immortal as the letters he wrote.

Lots of genitalia

There's just no way around including the exploration of medieval marginalia. Sure, there are cute animals and fun little scenes of dueling knights, and the comical butt trumpets, but there is also just so much genitalia, and in all manner of depictions. Sometimes they'll be attached to the body, sometimes they'll be attached in the wrong place, sometimes they'll be carried in baskets, there really is no limit to what these scribes were willing to do with the human nethers. One example, from the 14th-century manuscript "Roman de la Rose" (via an article from the University of Glasgow), shows a nun leading a monk with a rope tied around his penis. Then there's the nun with a basket of penises, picking more out of a tree full of them.

This may seem rather shocking in a highly religious society, with books that would only have circulated among the highest society, especially when written by monks. According to Paul Saenger (from the same University of Glasgow article), this may stem from a rise in private reading in the 15th century. This explicit material was seen in the privacy of one's own reading, rather than out in the open for all to see.

However, that doesn't quite account for the nun plucking penises out of a tree and all of the various dismembered members that dot the margins of older books. These, like butt trumpets and the like, might be chalked up to commentary on the text itself or a depiction of the written events.

Whatever's in the Voynich Manuscript

The most curious book of all time also counts itself among the most curious things found in a medieval manuscript because it is, in and of itself, a very curious medieval manuscript from cover to cover. Written in Europe sometime during the 15th or 16th centuries is as specific as anyone can get in understanding the Voynich Manuscript. It was found in 1912, and over the past century, attempts have been made to understand the book, but no strides have been made, according to Yale.

The contents of the book are written entirely in an unidentifiable script that cannot be deciphered due to its lack of connectivity to any known language. The illustrations are just as impossible, with 113 unidentified plant species, countless nude women with bulging bellies, indecipherable medicinal recipes, and arrays of cosmological and astrological signs and symbols that scholars can only guess at.

Whatever this book was intended to do and whoever wrote it remains one of the biggest mysteries to this day.