The Untold Truth Of Satanism

If there is an overarching belief somewhere, then it's all but assured that someone is going to go against the grain. Sometimes, it's pretty innocuous, like debating the superiority of chunky or smooth peanut butter, or whether or not pineapple belongs on pizza. But things get serious when you turn the focus of discussion towards religion. And when it comes to a religion like Christianity, which has dominated history and many cultures for thousands of years now, that sort of tension goes from simple to fraught very quickly. Just ask the Satanists.

Really, the scary image of black cape-clad Satanists doing evil isn't just the work of Christianity. The concept of a quasi-divine figurehead of evil, situated in opposition to a just godhead, predates Jesus by more than 500 years, according to the World History Encyclopedia. But who would worship such an evil figure, and why? As it turns out, the history of Satanism is about as convoluted and complicated as the history of Satan himself. It spans many centuries and is subject to about as many interpretations as there are individual Satanists nowadays. What's more, chances are exceedingly good that, no matter your preconceptions, you're going to be surprised by the history of devotion to the archfiend. This is the untold truth of Satanism.

Satan wasn't Christianity's enemy No. 1 for a long time

If you were to travel back in time, meet up with some early Christians, and ask them who they considered to be their worst spiritual enemy, you'd be pretty surprised. Depending on the time and place, they might point to execution-happy Roman authorities or even fellow Christians with different doctrinal notions, like those pesky Arianists. But bring up Satan, and chances are good that you'd be met with quizzical looks and blank stares.

That's because Satan didn't become the Big Bad of Christianity until centuries after the religion's founding. That's not to say there wasn't some form of "big time" Devil around in religious thought before then. According to the BBC, other religions like Zoroastrianism already had a pretty similar concept, with evil represented by an entity known as Ahriman.

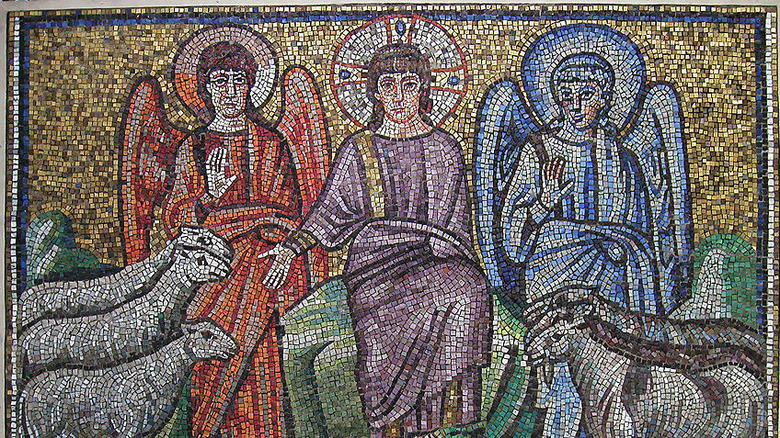

It took centuries for Satan to emerge as a similar leader of darkness within the Christian faith, reports National Geographic. The Bible only rarely mentions such a figure, with Satan even acting as a kind of prosecuting attorney on the side of God in the Old Testament. The animalistic Satan, diametrically opposed to all that is good and clearly influenced by images of pagan gods, actually arose in the middle ages. By this period, he became less of a heavenly functionary with unpleasant duties and more a malignant, actively evil being working to bring down Christians everywhere.

Tales of devil worshippers frightened medieval Christians

Given that Satan as the great adversary wasn't around for much of early Christianity, the idea of Satanists who honor him wasn't prevalent, either. But were medieval Satanists real? It's hard to say. Some contemporary sources claimed that orders like the Knights Templar and religious oddballs like the Cathars were in league with Satan, as Loyola University's Student Historical Journal notes. It could well be that the Church fathers, alarmed by the rise of powerful orders that threatened to undermine their authority, fabricated such claims. It could also be linked to lingering pagan practices, though such ideas remain speculative. It is interesting to note that, as The Conversation reports, some of the earliest tales of a Satanic conspiracy of witches were met with skepticism by a wide range of people.

There are hints that a small group of people may have participated in organized Satanism, even in a time when doing so would have meant almost instant torture and death upon discovery. These would have been the so-called "Luciferians," who were apparently active in 13th-century Germany. According to the Student Historical Journal, the Luciferians believed that Satan had been cast out of heaven on trumped up charges. Worshipping him and his host, they argued, would get them into paradise after Lucifer got around to overthrowing the Christian God. They received, as you may well guess, a very cold reception from Christian authorities at the time.

Satan became a magnetic antihero in the 17th century

Though there may have been groups of Satan fans scattered hither and yon throughout medieval Europe, it's safe to say that their beliefs were not exactly popular in the overwhelmingly Christian landscape. Yet, as the centuries wore on, that notion of Satan as a grotesque evildoer, represented by gut-churning images of medieval artists who weren't afraid to delve into some body horror, got some pushback.

Ironically, one of the greatest sources of this new cultural narrative came from a faithful Christian, John Milton. To be fair, Milton was a pretty liberal Christian, at least for 17th-century England, per Britannica. Yet it's remarkable that he would write his epic poem, "Paradise Lost," and feature the great evildoer as a kind of Romantic anti-hero. Whether or not Milton meant to create one of the first great emo figureheads isn't entirely clear, but that's certainly how readers interpreted the dark, brooding, and deeply individualist Satan of the poem.

Was this Satanism? No, at least not formally. But it's clear that Milton's work had immense cultural impact, to the point where people have unabashedly admired some of this particular Satan's characteristics, even drawing comparisons to the national character of the United States (via The Atlantic).

Some 18th-century spell books speak of pacts with Satan

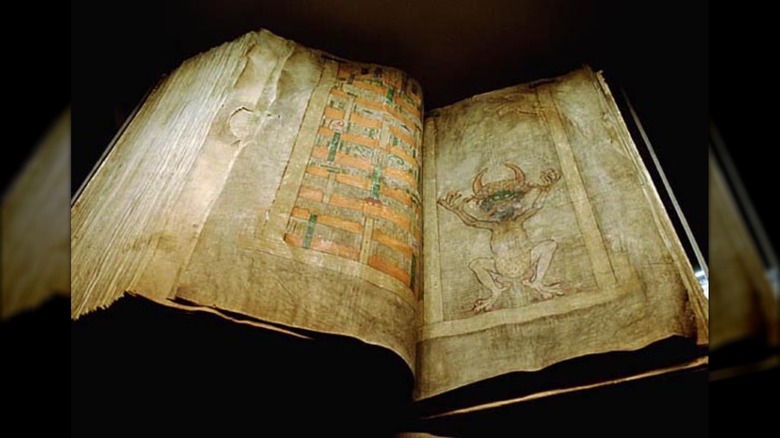

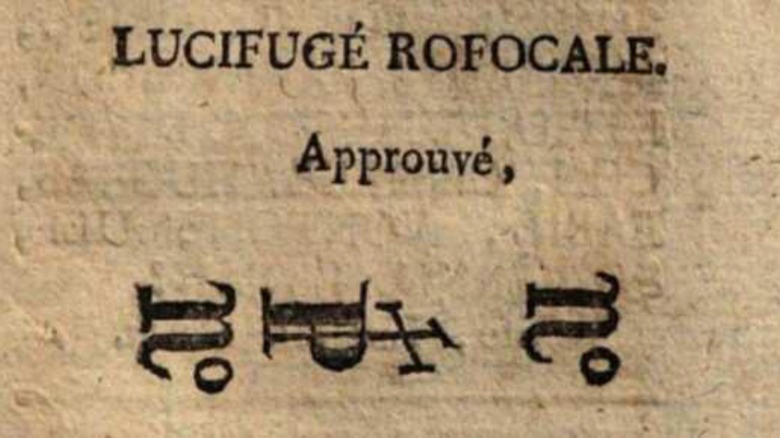

By the 18th century, the worship of Satan was in a complicated place. Did people gravitate towards him out of cultural interest? Or was there some genuine belief there? It's still difficult to tell just how many people really believed that worshipping Satan was a good idea, much less what percentage did so in organized groups. But a couple of spell books do contain tantalizing clues that people were still engaging in some form of early Satanism.

That's because the two books in question, the "Grand Grimoire" and the "Grimorium Verum," contain instructions for summoning Satan himself. According to Encyclopedia.com, the Grand Grimoire is supposedly derived from the writings of King Solomon himself, though good luck confirming that particular factoid. It does seem to have appeared by the 18th century, whereupon it offered up guidelines for summoning and dealing with demons. Likewise, the Grimorium Verum, also supposedly containing the wisdom of Solomon but appearing in the 16th century, claimed to give readers a road map to summoning Satan — assuming they could parse the dense and messy text (via Encyclopedia.com).

There is evidence of Satanic black masses being held in 18th-century Europe

Paris in the 17th century could be a treacherous place, at least if you were unlucky enough to know Louis XIV. Sure, the Sun King was incredibly rich and powerful, but his court was full of treachery. Your situation there was tenuous and could turn foul overnight if the king grew bored with you, or found you were no longer useful. Is it any wonder that some turned to devil worship?

At least, those are the allegations that arose during the explosive Affair of the Poisons. Part of the jockeying for position amongst paramours of the king left one woman, Madame de Montespan, desperate for Louis' attention. She turned to La Voisin, a notorious poisoner, to eliminate her rivals. What's more, she may have been one of a number of aristocrats who turned to Satanism for temporal gain.

When the goings-on were uncovered, a priest named Étienne Guibourg was revealed as the organizer of Satanic black masses meant to curry favor with Satan, according to "Magic as a Political Crime in Medieval and Early Modern England." The rituals reportedly involved black velvet, chanting, alchemical symbols, and child sacrifice. However, as "Satanism: A Social History," notes, Guibourg's confessions were taken under torture and can't be considered clear evidence of organized Satanists operating in 18th-century Paris or elsewhere. They were further muddled by the political intrigue and secrecy that surrounded any matters connected to the king.

Victorians often saw Satan as a symbolic figure

While there were certainly plenty of Victorians who were Bible-believing Christians, the advance of the 19th century saw more and more people take on a skeptical mindset. Even Satan himself, the biggest evildoer of all to many peoples' minds, went from being a big name worthy of fear or worship to a political symbol. He also garnered plenty of cultural currency as, yet again, a fascinating anti-hero in literary culture of the era, according to "Romantic Satanism."

However, there are hints of Satan as a religious figure here. Occultist Aleister Crowley routinely used Satan as a symbol in his work, though he clearly didn't buy into the idea of a traditional Satan hanging out in an underworld and working against the kingdom of Heaven (via History). Crowley, along with artist and writer William Blake, instead framed Satan as a rebellious anti-hero. But, where earlier artists like John Milton might have (weakly) protested that Satan was evil, Crowley and his like held up Satan as a figure worthy of emulation and respect.

While Crowley was busy being a contrarian, others were also taking Satan up as a spiritual figure. Madame Helena Blavatsky, founder of the mystical Theosophy, also took up Satan as a rebellious, admirable figure, per the journal Temenos. Though Blavatsky may not have been as immediately shocking as Crowley, she also used Satanism as a kind of shock tactic that surely compelled contrarian people and drew them to Blavatsky's circles.

Many claim there's a difference between rational and theistic Satanism

Broadly speaking, Satanic groups can be broken into those that use Satan as a symbol without genuinely believing in such a figure, and those that accept the divinity of the devil. So-called "rational Satanism," as it's defined by "Satanism: A Social History," may be ready to bring Satan as the symbol to their activities, but he's just that — a symbol divorced from any sort of individual reality. Satan may be an image, a useful fiction, but for rational or secular Satanists, there isn't really a literal devil anywhere in the proceedings.

Theistic Satanism, by contrast, is predicated on the existence of an actual Satan. According to Learn Religions, this figure isn't necessarily the archfiend as depicted in the Christian Bible. You may also encounter modern-day Luciferians or Setians (members of the Temple of Set), who believe in a very similar figure, but may not consider themselves to be Satanists in the strict sense of the word. Common themes amongst theistic Satanists include a focus on individual freedom, creativity, temporal success, and financial and material gain.

One of the first confirmed Satanic groups arose in Ohio

Contrary to what medieval church fathers would have wanted you to think, there isn't much evidence of religious Satanism until the 20th century. Certainly, previous centuries full of religious persecution and hysterical accusations didn't exactly set the stage for a Satanism that was practiced out in the open. According to some accounts, it finally happened in Ohio.

One of the first confirmed theistic Satanic groups, the Our Lady of Endor coven, reportedly came about in the state in 1948. At least, that's according to founder Herbert Sloane, though "Satanism: A Social History" questions that exact date. At least, a short article in a 1968 issue of the Toledo Blade does mention a "Lady of Indore Coven" operating in Ohio at the time. Regardless of the exact date, Sloane's coven was one of the earliest Satanic groups that unabashedly called itself as such, while also professing genuine belief in a Satan.

Technically, as Sloane wrote in a 1968 memo, his group believed in a spirit force that was historically known as "Satan" or an equivalent name. The exact details of the group's beliefs got pretty complicated, but it's enough for many to classify the coven's members as genuinely believing in a Satan.

The Church of Satan got attention for theatrical tactics

When it comes to modern Satanism, it's all but impossible to escape Anton Szandor LaVey. Before he founded one of the most notorious Satanist groups in living memory, LaVey was actually born Howard Stanton Levey, as per Britannica. His early life is fairly murky, though some accounts hold that he put in some time as a carnival worker and organist before coming to attention as a counterculture figure in 1960s San Francisco. Even his avowed enemies had to admit that LaVey was a pretty good musician, lending some truth to his potentially overblown backstory (via "Satanism: A Social History"). By 1966, though, he had clearly come to attention after he named himself the high priest of the Church of Satan, previously a gathering of occult students who adhered to principles of self-actualization and rationalism, as History reports. In 1969, he further cemented his church's spooky anti-authoritarian position with the publication of "The Satanic Bible."

The Church of Satan didn't just get attention for LaVey's ominous intonations or penchant for capes, though those were certainly features of the Church's recordings and publicity photos (LaVey also sometimes affected a horned hood that nowadays makes him look like a trick-or-treater). There were also the lurid rituals, free of bloodshed, but seemingly custom-made to shock one's churchgoing grandmother. These included frequent female nudity, from topless recruiting efforts (via History), to black masses where a woman offered her body as a living altar, as Britannica reports.

The Church of Satan splintered in the 1970s

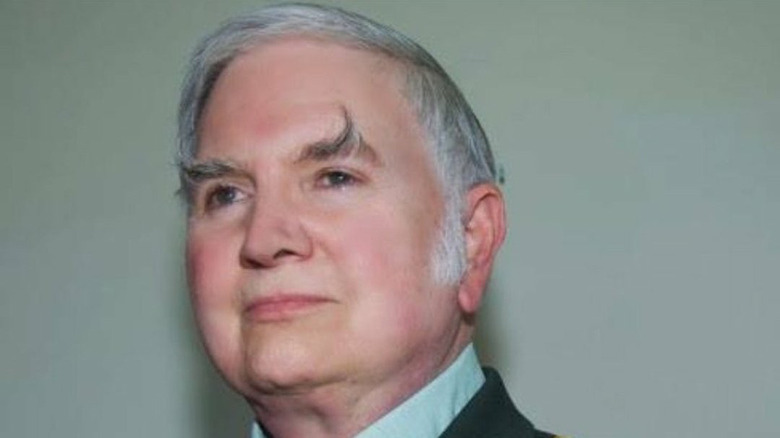

The Church of Satan, officially founded in 1966 by Anton Szandor LaVey, per History, accrued a collection of dramatic, anti-authoritarian personalities, so perhaps it shouldn't come as much of a surprise to learn that the Church of Satan soon splintered into many different Satanist groups. One of the most prominent is the Temple of Set, founded by a former Church of Satan bigwig known as Michael Aquino. A former U.S. Army officer who specialized in psychological operations (and sported truly monumental eyebrows), Aquino was an "ordained" priest in the Church of Satan. However, he grew disillusioned with LaVey's atheistic approach and created the more spiritual Temple of Set in 1975.

Dramatic as the clash of personalities was between Aquino and LaVey, they would not remain the only players in the Satanism game. As The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements notes, quite a few breakaway sects arose in the decades following the rise of the Church of Satan. These include the First Occultic Church of Man, the Church of Lucifer, Joy of Satan, the Temple of Hel, the Synagogue of Satan, and many, many more. Quite a few were helped along by the rise of the internet, with its ease of connection and communication that allowed like-minded Satanists to connect like never before.

A Satanic Panic convinced many that modern Satanism was alive and well

By the 1980s, it was clear that there were indeed Satanists out and about in the world, holding black masses, erecting statues of devilish deities, and selling copies of their Satanic literature. But, as much as people like Anton LaVey or Michael Aquino may have brought Satanism into the light and perhaps even made it a bit mundane for all the openness, there was still plenty of room for panic. As a few unfortunates would discover, hysteria over Satanism was alive and well.

The "Satanic Panic," as it came to be known, was a widespread conspiracy theory. It alleged that secretive Satanic groups were operating throughout the United States and beyond, conducting bloody rituals and abusing children in the name of their evil master. Those evil Satanists were also operating daycares, at least according to the virulent rumors. Though numerous people were affected by the panic, with some even being thrown in prison for decades-long sentences, no one uncovered any proof that Satanic ritual abuse had occurred to the extent that accusers said it had.

Though the height of the panic came in the 1980s and 1990s, it has deep roots in medieval witch hunts and modern conspiracy thought, as Vox reports. It may go by different names, such as QAnon, but the truth is that the fear of Satanists has never really left us.

The Satanic Temple isn't actually religious

While both the Church of Satan and the Satanic panic still have a presence in the modern era, chances are that neither are what comes to mind when you think of the cutting edge of Satanism. That honor (dubious or otherwise) goes to The Satanic Temple.

The Satanic Temple is firmly in the atheistic Satanism camp, as per Vox. Indeed, it could be more accurately described as a political organization. Members are often busy organizing against religious hegemony via eye-catching demonstrations, such as when The Satanic Temple unveiled a Baphomet statue. As NPR reported, members wanted to install the statue on the grounds of the Arkansas state capitol, where a monument to the Christian Ten Commandments had been placed in 2017. The Baphomet statue was never officially installed there, but, as of 2020, the Ten Commandments monument was under trial after The Satanic Temple, the ACLU, and numerous other plaintiffs brought a complaint against the religious monument on state property (via Arkansas Democrat Gazette).

Given the overlap between their belief systems, it may be surprising to learn that members of the Church of Satan and the Satanic Temple don't exactly buddy up on a regular basis. As TIME reported in 2013, some members of the Church of Satan took issue with The Satanic Temple's overtly political aims and even implied that the newer organization was piggybacking on the hard work of the Church.