The Unsolved Murder Of Sir Harry Oakes

Unsolved murders are, by nature, pretty fascinating to look at. Especially ones that happened long enough ago that hindsight now gives a birds-eye view of everything that happened. We see where the lives of those involved played out, how they were effected, and if later events tell us anything different about their involvement in the crime. And yet, despite the vantage point, they remain unsolved, seeing as how the evidence isn't exactly getting any younger. And, in time, all those connected fade away as well — no longer people of interest at all.

For Sir Harry Oakes, his unsolved murder is one for the storybooks. It's like a supersized game of Clue, where every suspect is as extravagant as the next, and each with an equally extravagant motive that ties into past lives and hidden secrets. There are links to the British nobility, the American mob scene, and Nazi sympathizers. And at the heart of it all, was a man who was truly an upstanding millionaire — and yes, those did actually exist.

Before the gold

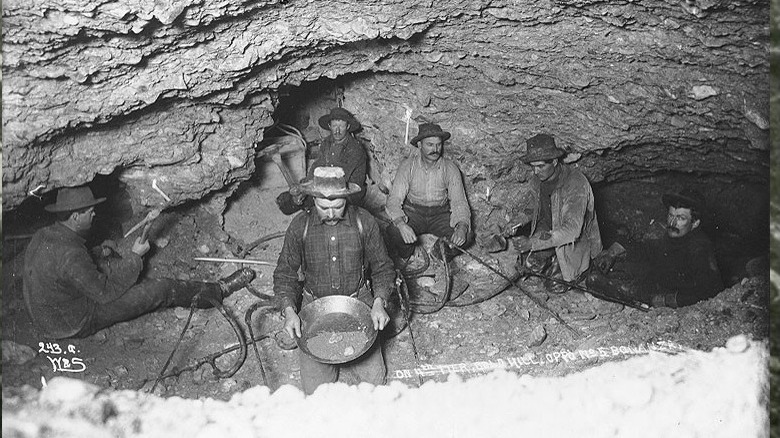

Harry Oakes had his path set out in front of him when he started school. He attended Foxcroft Academy, Bowdoin College, and Syracuse Medical School, according to Niagra Falls Info – the goal obviously being a career in the medical fields. But everything changed when he heard of the discovery of gold in Klondike, Canada. Suddenly, Oakes had a new fate — searching for, and ideally finding, gold. Nothing could talk him out of it.

After just two years in school, he dropped out and, according to Palm Beach Post, spent the next 15 years working laborious jobs across the world, searching — and failing — to find gold. His search took him to Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, and Death Valley, but he just couldn't find gold anywhere. He had no allies, no friends — he was at it alone (via Dujour). The sheer amount of perseverance it took for him to stick with it for that long with no results is astounding, but fortune didn't seem keen to find Oakes. Having gone effectively broke, he went back to Canada, where he hopped a train without money for fare, and he was dropped near Kirkland Lake.

Near Kirkland Lake, a local man told Oakes that there was gold in the area, and Oakes took his word for it. He wired his mother for the last of her money and set out, perhaps for the last time, to find his fate.

Eureka!

Friendless and penniless, Harry Oakes' good luck finally found him at the only place the train would take him — Kirkland Lake. There, fate led him to a massive gold mine that would change his life forever. Literally.

It's hard to see it as anything other than fate. After nearly 15 years of fruitless searching, Oakes had found gold in the last place he could actually go. He had no money to make it anywhere else, and no one left to call. He was truly at the end of his rope, and that's where, of all places, he found what he had been looking for. According to Artsfile, it was one of the biggest gold finds ever. Everything he had ever wanted, all right there in one place.

Canadian historian Charlotte Gray (via Artsfile) highlights Oakes character in his determination: "He was that kind of obstinate blinkered individual who can feel that fortune is just beyond them. They are so single-minded they forget everything else."

Having become obscenely rich seemingly overnight, Oakes had to figure out what to do with his mass of wealth — wealth that he had never seen before, being born to a middle-class family. And he chose well.

Money to a good cause

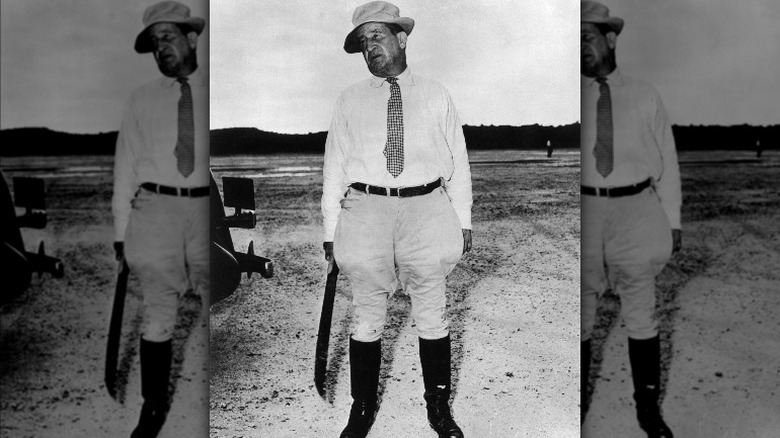

Harry Oakes could very well have used his wealth to amass more wealth and join the likes of the Carnegie and Rockefeller families as cultural powerhouses, but he chose not to. Instead, after securing a comfy and luxurious home for his family in Niagara Falls, he diverted some of his fortunes towards the Niagara Parks Commission, according to Niagara Falls Info, to help protect the park's diminishing shoreline.

However, Canadian taxes proved rather burdensome. According to Niagara Falls info, the Canadian government was claiming as much as 25% of all the gold mined in Oakes' motherlode so, after 10 years, he and his family moved to the Bahamas and settled in Nassau, where he found more worthwhile endeavors to invest his money — all the while paying less taxes.

Portland Monthly details his incredible and charitable expenditures as he spread his wealth around, and not just in the Bahamas. He bought and improved a hotel, he added more facilities to the local hospital, beefed up public transportation, employed the native population, and spearheaded the poverty gap that plagued the island. His wealth also reached London, where he donated the equivalent of $500,000 to a hospital, as per Fox23.

This quickly gained the attention of British royalty, and Oakes was awarded a baronetcy, making him Sir Harry Oakes.

Murder!

As the Palm Beach Post details, on July 6, 1943, Harry Oakes was due to meet his family on vacation in the United States. However he ended up staying home for another day show he could give a tour of his 1,000-acre sheep farm to a newspaper editor and his friend, Sir Harold Christie.

The results of this decision proved catastrophic. On the night of July 7, after concluding an evening of reveling in his Nassau home, Oakes went to bed but never woke up. He was murdered that stormy night, and the crime scene the following morning was anything but ordinary.

Christie, who had been staying in a guest room, was the first to discover Oakes body. According to Crime and Investigation, Oakes' murder was bizarre enough to bring up parallels to ritualism or attempted concealment. His skull had been fractured in four places, and his was face covered in blood. His body has also been unsuccessfully set on fire. Left behind were a bloody handprint smeared on a Chinese screen, muddy footprints dotting the floor up the stairs to the room, and feathers from his pillow on his body.

The Suspects

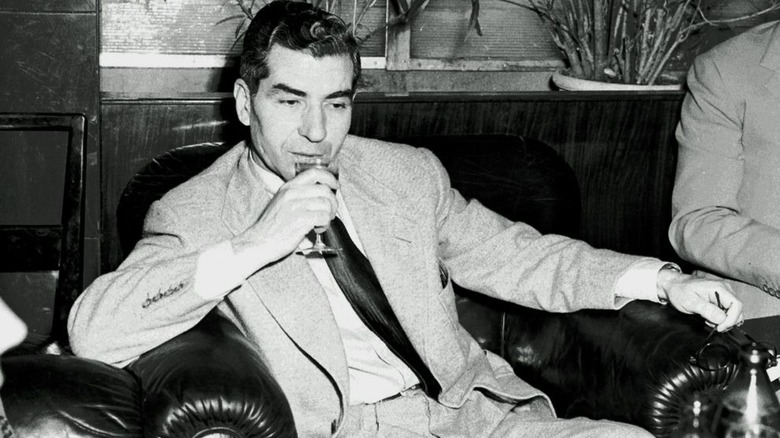

The list of suspects, according to Crime and Investigation, was as diverse as it was glamorous. Given the wealth on Nassau, Harry Oakes had been partying with the who's who of various walks of life. Of course, first on the suspect list was Harold Christie, the last man to see Oakes alive. Christie also had a link to the famous mobster Lucky Luciano and Frank Marshall — the latter of whom was a suspect himself. Marshall had been pressured by his mob bosses to get building on Nassau, and supposedly Oakes stood in the way of his production.

Then there was Axel Wenner-Gren, a Swiss-born businessman and proud owner of the largest yacht in the world. Crime and Investigation reports that Wenner-Gren made his money by selling light bulbs and household electrical equipment. But then there's the kicker — he was good friends with Nazi bigwig Hermann Goering and was suspected of being a German spy.

The duke of Windsor himself was a suspect, having recently abdicated from the throne and been appointed governor of the Bahamas. He, too, had some seriously strong ties to the Nazis, and Oakes could well have learned about them.

And last but not least was Oakes son-in-law, Alfred de Marigny. De Marigny was a rich young man, who had already been married twice before marrying Oakes' daughter Nancy (via Time). It was also suspected that his fingerprint was found at the scene of the crime.

The Evidence

As Crime and Investigation details, the scene of the crime was just plain wild. There was blood everywhere, feathers blowing about, and gasoline had been used in an attempt to burn Harry Oakes' body. A bloody handprint was on the Chinese screen, and muddy footprints were tracked along the house leading up to Oakes' room. Surely there were enough pieces for the police to figure things out.

Rather than employ the local police, however, the duke of Windsor hired two Miami detectives to work the scene. Capt. James Barker and Capt. Edward Melchen were supposed to be fingerprint experts, but they proved inept in nearly every regard. They forgot to pack a latent-fingerprint camera, allowed visitors into the home to see where the body had been discovered, and made no attempt to discourage them from handling objects within the house and in the actual scene of the crime.

And before the bloody handprint could be investigated in preparation for the trial, it was scrubbed away, leaving the two detectives and local police with very little to make an arrest on. Yet, they still had their primary suspect, and they had evidence against him, even if it wasn't the most compelling.

The case against Axel Wenner-Gren

Axel Wenner-Gren, like most of the rich and famous on Nassau, was quite the character. He'd made a fortune selling lightbulbs and electrical equipment and had a reputation as a wily businessman with a resume for being someone who just knew what the next hot product was. Add to that a statement from his own foundation, which states that he "had the foresight to recognize the potential of both the domestic vacuum cleaner and door-to-door marketing techniques."

But those are just the things that are remembered of his front-facing business endeavors — the things that his proponents remembered him for. As was the case with so many of the "dignitaries" on Nassau, there was an underbelly to Wenner-Gren that gave rise to suspicions — suspicions that landed him on the suspects list.

Given that Harry Oakes was, by all accounts, an upstanding gentleman whose biggest flaw was fleeing Canadian taxes, he was also not one to cow to unsavory business partners. Wenner-Gren had a close personal friend in notorious Nazi Hermann Goering, and there were whispers, according to Crime and Investigation, that Wenner-Gren was a German spy himself. The motive behind him being the killer needed to be no deeper than that — perhaps Oakes found out about Wenner-Gren's Nazi ties and his status as a spy, and that's what did him in.

The case against Alfred de Marigny

Alfred de Marigny was the son-in-law of Harry Oakes, married to his daughter, Nancy Oakes, reports Crime and Investigation. While she was his third wife, Nancy herself was steadfast in her belief that her husband had nothing to do with the murder of her father and even hired private investigators to back her claims up. De Marigny also had numerous alibis from dinner party guests who vouched for his attendance at a party at the time the murder was being committed (via the New York Times).

However, de Marigny was also not well-liked among the Bahamian crowd. According to the Independent, he was considered a poser, who liked to sponge off the wealthy. Certainly not helping his case, the Palm Beach Post reports that Oakes had changed his will a couple of years prior, perhaps cutting out de Marigny from any part of it.

To further pile on de Marigny, who retained that he, himself, was a victim, the physical evidence was pretty overwhelming. He had singed hair on his arms, and his fingerprint was supposedly found at the scene, though that evidence had since been destroyed. Then there was the matter of him having a light on all night, perhaps burning evidence, or perhaps just doing a little light reading.

Still, his dinner guests were quick to set the record straight, saying that he had singed his arm hairs on a candle.

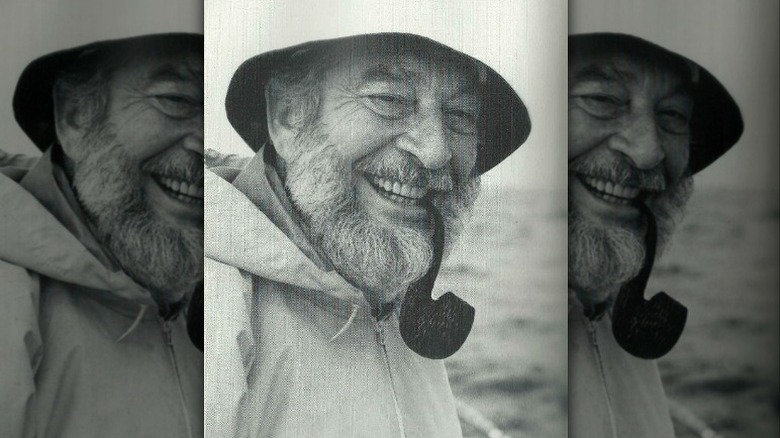

The case against Harold Christie

The last person to see anyone alive is always going to be suspected in a murder, and that's where Harold Christie found himself. He'd been the only other person in the Oakes mansion when the man himself was killed, and he was the first to discover the crime scene. Thus, he would have had time to get his ducks in a row before calling the police to report the find.

However, according to the New York Times, Christie, like Harry Oakes, ended up being knighted for his services to the Bahamas. He was also later elected to the Bahamas House of Assembly and founded Bahama Airways — all things that Oakes himself likely would have done, or at the very least endorsed, had he lived long enough to do so.

But there's a deeper motive that links Christie to the murder. According to Crime and Investigation, Christie had developed a loose connection with Lucky Luciano through Frank Marshall, the latter of whom had intended to get around local restrictions and build casinos on the island so long as they could get the other Nassau bigwigs to help — one of which was Oakes, who seemingly had no interested in underhanded ventures such as this.

Christie also had numerous loans with Oakes, loans that Oakes could collect on at any moment and effectively ruin Christie's finances (via the Palm Beach Post). As such, Christie may well have wanted to see Oakes out of the picture for multiple reasons.

The case against Frank Marshall

While Harold Christie had a link to Frank Marshall, Marshall himself was suspected as well. He had American business partners, all of whom were suspected of being in the mafia, according to Crime and Investigation. In fact, one such partner was notorious mobster Lucky Luciano himself.

It was Luciano's idea to build casinos on the island to bring in a new stream of revenue to the American mafia, but he knew he needed the help of the power-holders on the island — namely Harry Oakes, Christie, and the duke of Windsor. The latter two were already on board, which left Oakes to either get on board or get out of the way.

Marshall would have been feeling the pressure to get the job done, and with Oakes not on board, the simplest solution may have presented itself as murder. Not to mention the fact that the manner of the murder and how grisly and gruesome it was reflects the type of killing the mafia was known for.

And then there's the matter of Marshall himself being in Nassau at the time to scout out potential locations for Lucky Luciano's casinos, making him a clear suspect with clear motive, as well as having access to Oakes with Christie staying in the house the night of the murder.

The case against The Duke of Windsor

The duke of Windsor, formerly King Edward VIII, was exiled by the British government after his abdication in 1936. Britannica highlights the duke's time in Germany, where he was praised by the Nazi party and interviewed by Adolf Hitler himself. This relationship led to Hitler's plans to reinstate the duke as king if the Nazis had their way, which prompted Winston Churchill to be rid of the duke, giving him the governorship of the Bahamas just to get him out of the country. It's very possible that Harry Oakes could have found out about the duke's Nazi ties, and perhaps even intended to do something about it.

The case against the duke is deeper than that. He was close personal friends with the Miami detectives (via The Guardian) who completely bungled the investigation, and it had been the duke himself who called on their assistance rather than relying on local police, according to Crime and Investigation. What had seemed like an act of good will may well have been part of the plot to cover the scene.

According to British-Bahamian journalist John Marquis in his 2006 book "Blood and Fire" (via the Palm Beach Post), the duke "was involved in an enormous conspiracy and cover-up," along with whatever role he may have played in the murder itself.

The trial

Thirty-six hours after the body was found, the police made their arrest — Alfred de Marigny, the son-in-law of Harry Oakes, husband of his daughter, Nancy Oakes (via Crime and Investigation) — based on the supposed fingerprint found at the scene of the crime, as well as the physical evidence stacked against him.

However, during the lengthy trial, no one could verify that the fingerprint actually came from the scene of the crime. The bloody handprint had been washed away, and with no murder weapon and a cloud of doubt over what had been used to kill Oakes in the first place, the case crumbled relatively quickly, and Marigny was acquitted of the crime. There was a catch to him being acquitted, though. According to the Palm Beach Post, he was also immediately thrown out of the Bahamas. With nowhere left to go, he went to Cuba before turning up years later in Hollywood, no longer married to Nancy.

The murder remains unsolved to this day. While many have investigated and theories abound, the prevailing thought is that the duke of Windsor had to be involved, given his motivation and the sheer multitude of ways he helped flub the investigation. John Marquis, author of the book "Blood and Fire," added that it was "highly likely the two Miami cops participated in the cover-up, under direction from the duke" (via the Palm Beach Post).