The Wild Hunt Legend Explained

There's a lot to be said about our modern, 21st-century life. It's filled with a lot of great things, like online gaming, refrigerators, and smartphones, but it's also an undeniable fact that society has lost something, too. It's easy to look back at the stories our ancestors told and roll our collective eyes because clearly, there's no such thing as a half-fish, half-monk that lives in the oceans and (presumably) serves the higher powers alongside his fellow underwater clergy members. Right? At the times these tales were told, though, they were a brilliant way to explain natural phenomena. It's that imagination and story-telling that deserves some serious respect.

Imagine: Midwinter nights, somewhere around the 10th century. There's no electricity, no lights aside from candles and the fires burning in the hearth to drive back the darkness and the cold. Food stores are scarce, and people have to rely on what they put aside and hope it's enough to get them through until spring. The land outside is snow-covered and frozen, the birds have fallen silent, the wind whips through the naked trees ... and sound? Sound carries.

It's not surprising, then, that Norse Mythology says ancient people from across Europe have told tales of just what those distant sounds are, carried on the icy winds of a midwinter night. The barking dogs, the horses ... the noises no one could explain. They were the sounds of the Wild Hunt, and it's a good thing everyone was safely inside.

Different areas had different hunts ... but here are the basics

The idea of the Wild Hunt is actually equal parts vague and widespread. As Norse Mythology explains, civilizations from the ancient world to fairly modern times — and from across Europe — all told their versions of the Wild Hunt story. The heart of the story stays the same, and it's basically the tale of a group of otherworldly figures who ride across the land in the middle of the night, with one particularly terrifying figure at the head of the hunters.

Different communities called this supernatural hunt different names. Some places in Scandinavia called it the Terrifying Ride, some places in Germany shared whispered tales of the Furious Army, and according to Orkneyjar, other places used the term the Raging Host. Just who they were said to be varied by location, too: Sometimes they were the restless spirits of sinners, and sometimes they were undead armies, souls in Purgatory, or ghosts cursed to wander the land for eternity by other supernatural creatures (via Medievalists).

Most Wild Hunts were said to be accompanied by hunting dogs, and whoever the condemned souls were, they were generally said to be riding black horses. What they were looking for also changed with the telling — some were searching for forgiveness, others were looking for a mythical, magical animal, and in some places, they were simply condemned to wander forever without being able to dismount.

The most famous Wild Hunt was Odin's

While there were a lot of different, local versions of the Wild Hunt story, one of the most famously and oft-told was of the one led by Odin. According to History Today, Odin was said to lead a massive hunt across his entire domain each midwinter, and it was a terrifying ride.

Joining him on the ride were pretty much anyone and everyone ever said to join in such a hunt: Behind him trailed the souls of the dead, mythological creatures like trolls, and some of his fellow deities. That included Thor, who rode alongside him in a chariot drawn by goats. Odin, meanwhile, rode his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, and — perhaps unsurprisingly for a god of the wind — he caused storms to sweep along behind the chaotic ride that was also known as Asgardreia.

What were they looking for? According to Orkneyjar, they were looking to gather the souls of the recently dead, who would be condemned to join their annual ride. Anyone who was unfortunate enough to glimpse the riders but not be swept away was said to be condemned to an imminent death, while the passage of the riders and the storm that followed was believed to herald disaster, death, plague, or starvation. Given the harshness of ancient winters with none of our modern comforts, it's safe to say that the portent was generally accurate.

There were scores of people said to lead Wild Hunts

Odin, says Orkneyjar, was just one possible leader. Others were the divine Herne the Hunter and (in Wales) Gwynn ap Nudd, while in other areas, the figure at the head of the hunt was even said to be a historical ruler like Holy Roman Emperors Charlemagne or Frederick Barbarossa.

In some narratives, the story gets even more convoluted. One reported leader of a Wild Hunt was a man named Hans von Hackelnberg, and it's unclear if he was purely a product of folklore or a historical figure. Either way, it was either 1521 or 1581 that he was mortally injured by a boar while he was out hunting. Before he died, he wished that he didn't pass on to the afterlife and was instead left to hunt the earth forever — so, he was. The footnote to this story is that some folklorists think "Hackelnberg" is a version of an old name for Odin, "Hakolberand."

Norse Mythology says that in Germanic areas, the leader of the Wild Hunt was given all sorts of names, from Perchta (the Christmas witch with a penchant for disemboweling her victims) to Holle/Hulda (the goddess of women) and a mythical king called Herla. He, says Medievalists, returned to the land of the living after attending the wedding of a dwarven king and was unable to dismount from his horse without turning to dust — a fate suffered by many of his men.

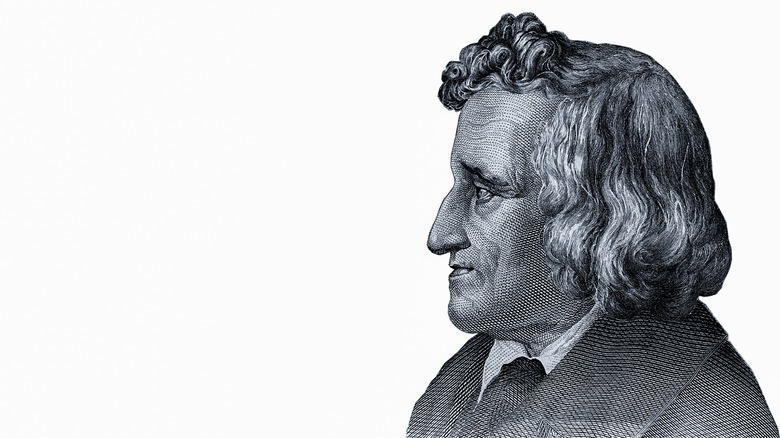

The concept was cemented by Jacob Grimm

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm might be most famous for their fairy tales, but as Pook Press says, the brothers were much more than folklorists — they were also librarians who studied linguistics, culture, politics, and the nation's legal history. They're the reason that stories like "Rumpelstiltskin" and "The Frog Prince" were plucked from the relative obscurity of Germany's oral folklore traditions, written down, and translated to be shared around the world. According to History Today, Jacob was the first to write down the Wild Hunt legends.

In 1835, he published "Deutsche Mythologie," in which he researched the connections between the Wild Hunt — or wutende heer — and both the old pagan gods and the emergence of Christianity. He wrote that when Christianity changed the way people worshiped, "[Odin] lost his sociable character ... and assumed the aspect of a dark and dreadful power, that still had a certain amount of influence left. ... he wandered and hovered in the air, a spectre and a devil."

Grimm also recorded similar tales, and interestingly, one of those had the hunt set during Switzerland's longest summer nights. That, he wrote, was led by "a subterranean infernal deity" that would destroy anyone who got in the hunt's path. Others told of clever peasants outwitting the gods of the hunt, and another told of a woman who — after claiming the hunt was better than heaven — found her daughters turned into hunting dogs, and they were all condemned to hunt for eternity.

A wild hunt was reportedly sighted in 1127

Scribes and historians started compiling "The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle" back in 890. The British Library says that the books were meant to be a complete chronicle of each year in English history. In 1127 — right before a section that recounts King Henry's conflict with the Earl of Flanders (and the earl's death) — was a passage that tells of a Wild Hunt heard and seen by countless witnesses. The scribe wrote: "Let it not be thought remarkable, the truth of what we say, because it was fully known over all the land, that immediately after he came there, then soon afterwards many men saw and heard many huntsmen hunting."

Clearly, the poor scribe knew that no one reading this at any point in the future was going to believe any of this, and if there's anything truly great about history books, it's when they start with a disclaimer that says, "Really, we swear, this sounds impossible, but it really happened." He went on to describe hunters "black and huge and loathsome," who were seen in the deer park of Peterborough. They were riding, some on huge black horses and others on black rams, and they were accompanied by their black hounds. Monks from the abbey and townsfolk alike testified that they had seen the hunters, estimating that there were between 20 and 30 tasked just with blowing the horns. They appeared every night during Lent, and believe or don't believe — there's no denying that's eerie stuff.

Christians co-opted the Hunt in the 12th century

Early Christians were good at co-opting pagan stories and making them serve a Christian narrative, and according to Medievalists, that's exactly what happened with the Wild Hunt in the 12th century. The Christian version was first recorded by the writer Orderic Vitalis. He claimed the story had been told by a priest named Walchelin, who had the bad luck to get up close and personal with the hunt.

Walchelin, the story says, was walking on the outskirts of his parish on January 1, 1091. He heard a group of riders approaching and, thinking they were military men, ducked off the road to hide. He didn't get that far, though, and was stopped by a massive figure carrying a mace. The figure told him to stand and watch, so he did — thousands of people went by, all carrying their worldly possessions, many sobbing and crying. It wasn't long before he recognized some of them as members of his parish who had recently died.

Walchelin decided to try to grab one of the horses to follow the procession and, in doing so, got into a bit of a scuffle with one of the knights. Another came to his rescue and revealed himself to be the priest's dead brother. He explained that he had no choice but to follow, condemned to walk with the procession until he was deemed penitent and was allowed to pass on from this purgatory.

The Christian wild hunt was based in the idea of the walking dead

When Christianity swept across Europe, it swept the Wild Hunt up in new lore. The riders were no longer gods or mythical creatures — they were souls trapped in a concept that Medievalists says was only recently being fully developed: purgatory. The idea was that people who weren't quite bad enough for hell but not exactly good enough for a "Do Not Pass Go, Do Not Collect $200" ride straight into heaven needed to spend some time in purgatory being punished and atoning for their sins. In the Middle Ages, it was believed that these souls could appear to those they knew in life and ask for prayers that would help speed up their journey.

Still, what about the Wild Hunt? The eye-witness account of the priest Walchelin suggested that those riding in the hunt were those being punished for sins. His descriptions of some of the riders are graphic: Women rode on saddles outfitted with burning nails, and men were tied to tree trunks that others labored to carry. Demons sat on the backs of some, digging burning spurs into them and urging them to go faster. One knight who seized a mill that had been the property of a man he'd lent money to was forced to carry a burning piece of the building in his mouth, while others carried weapons that burned them. The only comfort was that it would end ... eventually.

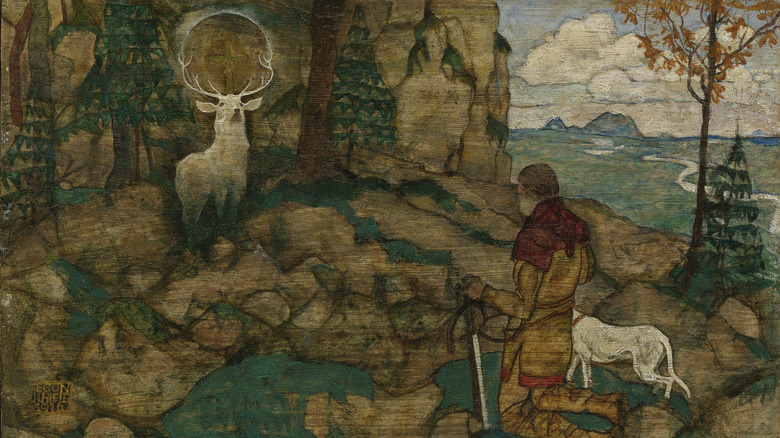

One saint was said to lead a hunt

The Christian clergy had a very important lesson to teach those they were converting, and that was getting them to accept the idea that the only way anyone was going to have a peaceful afterlife was to embrace God. One of the ways they illustrated just how important it was to live an entire life according to Christian doctrine was to put a saint at the head of the Wild Hunt. According to a local folklore blog, Bonjour From Brittany, some stories from this particular area of Europe put a nobleman named Hubert front and center in the Hunt. Hubert, the story goes, was born in 656 and later lost both his wife in childbirth. In despair, he retreated to the woods, where he did nothing but hunt — even on Good Friday. It was on one of those sacred days that he came across a white stag with a crucifix over his head. (That, says The Washington Post, is the imagery of Jägermeister.)

The stag warned him that he was on the path straight to hell, and while Hubert did change his ways and was later made the patron saint of hunters, Brittany folklore says that he still needed to pay for the sinful life he'd led. And pay, he did: He was condemned to lead a Wild Hunt that was aptly called Saint Hubert's Hunt, and he would keep riding until Judgment Day.

King Arthur was perhaps the most unlikely of Wild Hunt leaders

There are scores of stories about King Arthur, and he's always a righteous sort of guy. He's not, in other words, the figurehead that might be expected to be seen at the head of a Wild Hunt, something that's usually reserved for pagan gods, demonic creatures, and sinners. Still, Cornwall Guide says that's exactly what he reportedly does. Stories of King Arthur's Wild Hunt are told in Cornwall — where there's even a King Arthur's Lane that's said to be a favorite haunt of the riders — and in Wales and Brittany. But why?

Bonjour From Brittany says that Arthur was placed at the head of the eternal hunt for reasons that had nothing to do with being a king or a knight. There are a few different stories about Arthur the hunter, and they all tell of crimes against the church. In one, he left a Sunday service to answer the baying of his hunting dogs, while another says it was an Easter mass that he left for the hunt. Yet another says that he was in mid-hunt when he and his pack came across a priest, and he didn't stop. All of those were, apparently, enough to condemn him to hunt until Judgment Day.

Anyone outside risked being swept away

There's no denying that the stories of the Wild Hunt are terrifying, no matter who leads it and who rides alongside them. That wasn't the only part of the story, though, and tales also told of what would happen to anyone unfortunate enough to witness the Hunt in person. Medievalists claims that some stories — particularly in Ireland — said that the Hunt would attack anyone and anything in their path, up to and including entire armies. Bonjour From Brittany reports that many stories from this area of Europe say that the only creatures safe from the Wild Hunt were wild animals — any domestic animals, livestock, or people who found themselves in the riders' path would die.

Tales translated by the University of Pittsburgh's D.L. Ashliman have still more variations. A story from Cornwall suggests that the power of prayer could protect a person faced with otherworldly hunters, while a German tale recounted the story of a poor woman who came across the Hunt while walking home. She was saved by the intervention of an underground spirit called the Mine-Monk and given enough silver to live comfortably for the rest of her life.

Not all German tales work out so well: There's another of a mill worker who heard the Hunt approach and went out to see them for himself. He called out to the riders, who responded by throwing a woman's severed leg at him.

Wild Hunts typically had connections to mythical dogs

For all the variations in the stories of the Wild Hunts, they all have one thing in common: dogs. Dogs always accompany the Hunt, but just what they are varies by the telling. The BBC says that the all-black dogs of the Wild Hunt have been connected to other tales of hellhounds in Britain, particularly later stories like the 16th-century hound of Suffolk, known as Black Shuck.

Orkneyjar suggests that the motif of the black dogs accompanying the Wild Hunt goes all the way back to ancient Greece when it was said the goddess Hecate would wander the night with her dogs. Similarly, French stories told of a Wild Hunt led by a woman named Mesnee d'Hellequin — a version of the Norse goddess Hel — and she demanded the sacrifice of black dogs and lambs. In Wales, the Wild Hunt led by Gwynn ap Nudd — the Lord of the Dead — was said to include pure white dogs with red ears. Interestingly, those hounds show up in the folklore of other parts of Britain, where they're called Gabriel Hounds and were said to herald disaster.

There's one more weird story here, too. In some areas — particularly in northern Europe — it was said that when a Wild Hunt passed by a town or village, a small, spectral black dog might be left behind. It was up to the villagers to care for the dog for the coming year ... lest the Hunters return.