This Museum Of Criminals Includes The Head Of Its Builder

The Italian city of Turin is not as popular with tourists as other destinations such as Rome, Venice, Milan, or Florence, but it is home to some museums that are worth a visit (via Travel Mag). For instance, those who love cars will enjoy visiting Museo Nazionale dell' Automobile (The National Automobile Museum), which houses hundreds of vehicles from various car brands. On the other hand, Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum) is ideal for history buffs who enjoy viewing and learning about ancient artifacts.

For tourists who appreciate all things macabre, Turin offers Museo di Antropologia Criminale (Museum of Criminal Anthropology) which boasts Cesare Lombroso's vast collection of human skulls, death masks, brains, and artwork created by criminals. Lombroso was a well-known criminologist and physician, and documents about his research are found within the museum as well. The museum features Lombroso's massive collection of specimens throughout the years, and initially, there was controversy regarding public access to the items included in the museum because of their morbid nature.

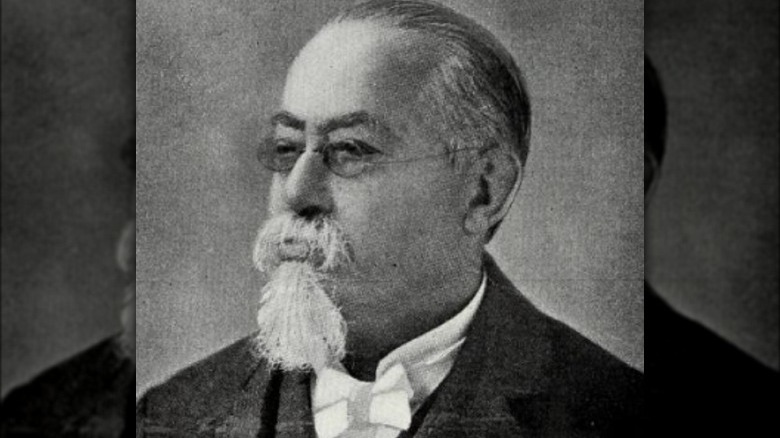

The man behind the museum

Cesare Lombroso, known as the founder of criminal anthropology, was born in Italy on November 16, 1835. He pursued studies in the medical field and worked as an army surgeon and a professor of psychiatry before being appointed as the director of a mental institution in 1871 (per Britannica). In the years following, Lombroso also taught forensic medicine and hygiene, as well as criminal anthropology.

During his time as a professor, Lombroso studied the skulls of numerous criminals, and it was during that time that he developed his theory regarding the correlation between the shape of skulls and criminal behavior, as reported by Dark Tourists. In essence, Lombroso concluded that criminals were born and not made, and he formed his theory by collecting countless remains of criminals and comparing their physical features. It was also during that time that Lombroso started collecting the skulls and specimens of his subjects that would eventually be displayed in the Museum of Criminal Anthropology.

Cesare Lombroso's theory

Cesare Lombroso published his findings in 1876 in a book titled "The Criminal Man," wherein he proposed that certain people have biological traits that make them prone to being criminals. According to his studies, these people have atavistic — meaning ancient or primitive — features, as noted by Simply Psychology. Lombroso examined the skull of Giuseppe Villela, a well-known criminal in Italy, and found that the back of his skull had an irregular shape that looked much like the skulls of primates. After seeing the same in other skulls that he studied, he posited that criminals were less evolved than non-criminals and were prone to turning to a life of crime.

In addition to the skulls, Lombroso also examined the weight, height, and sizes of various body parts. Based on his findings, 40% of his subjects had atavistic features. Today, however, Lombroso's theory has become obsolete, as his techniques and data gathering have been deemed weak, per the National Library of Medicine. Still, he is considered important in the criminal anthropology world, as he was one of the pioneers who scientifically studied criminality.

The Italian School of Criminology

By the end of the 19th century, Cesare Lombroso — along with fellow criminologists Enrico Ferri and Raffaele Garofalo — established the Italian School of Criminology wherein he developed his research on criminology based on various concepts, as noted by Harvard. Lombroso was a reputable criminologist during his time, and many people consulted with him regarding his thoughts on criminals and their physiology.

Lombroso came up with some characteristics that he believed were common for criminals. He noted unusual ear size, large chins, long arms, and a sloping forehead as some of those (via The Vintage News). In addition, he also stated criminals do not feel remorse for their actions and are more impulsive. One of his beliefs that have since been proven false was that race was a factor in criminality, and he stated that white people were the only ones who "have reached the ultimate symmetry of bodily form." All these observations led him to the conclusion that criminals are born and not cultivated.

The items in his collection

Cesare Lombroso had amassed quite a large collection of biological specimens from his years of work, which he kept in his own home. In 1877, his collection was transferred to a laboratory, and it was eventually opened to the public in a museum in 1892, per Atlas Obscura. As previously mentioned, the items mostly consist of skulls and brains of his test subjects, but part of the collection also includes other items related to criminals, such as pieces of evidence in crimes, drawings created by perpetrators, weapons used by criminals, and other interesting artifacts from the 19th century.

Lombroso's daughter stated that her father was always studying and collecting items no matter where he was. As reported by Cultural Heritage Online, Lombroso acquired the first few items in his collection during his time as a surgeon in the army. He preserved and kept the brains and skulls of dead soldiers, and as the years passed, his collection grew to include specimens from prisons and asylums.

Cesare Lombroso's severed head

The Museum of Criminal Anthropology relocated and closed several times throughout the years, but it found its permanent location in Turin where it remains open to the public to this day. Lombroso died in 1909 at the age of 73. In his will, as noted by The Florentine, he stated that he wanted his body donated to science. His severed head is preserved inside a jar and displayed as part of the collection for everyone to see in the museum.

In 2009, on the 100th death anniversary of Lombroso, the museum was renovated and the items were displayed in various collections. The purpose is to provide visitors with a chronological look at how the criminologist came up with his theories (via Museo di Antropologia Criminale). In addition, the museum also provides information about the errors in Lombroso's theories and how his studies have since become obsolete.