How A Language Error Could Have Led To The Murder Of Botanist Charles Budd Robinson

Language is complex, ever-evolving, and, most importantly, based on the speaker and the hearer understanding each other. That's not always how it works out, however. Even people who ostensibly speak the same language can get heads scratching. For example, if an American goes to a department store in London and asks about pants, they'll be taken to the underwear department; that's because in British English, "pants" means "underpants" (they say "trousers").

When it comes to different languages, all bets are off. More than one tourist has stepped into it while in a foreign land, either through trying and failing to communicate in the local language or failing to understand what a local is telling them. A century ago, a famed Canadian botanist died under circumstances that are debated to this day. And at least one author believes that a simple translation error, or maybe even fumbling over his own tongue, may have cost him his life.

Who Was Dr. Charles Budd Robinson?

Charles Budd Robinson — and yes, Budd is part of his actual name and not a nickname stemming from his field of work — was born in Canada in 1871, according to Global Plants, (via JSTOR). After completing his university education, his career in botany took him here and there over the years, from teaching posts at Canadian universities to different stints at different times with the New York Botanical Garden and a few years in Manila working with the Philippine Bureau of Sciences. He died while doing research in Indonesia in 1913.

His contributions to the field of botany are difficult to qualify. He died at a comparatively young age, so his name could possibly have been up there with other great biological scientists, such as Charles Darwin, had he lived longer. And though none of his research was or is particularly groundbreaking, he did publish several books and/or academic papers, including this one via Google Books, this one via JSTOR, and this one via Dalhousie University, his alma mater.

Colonialism and Indonesia

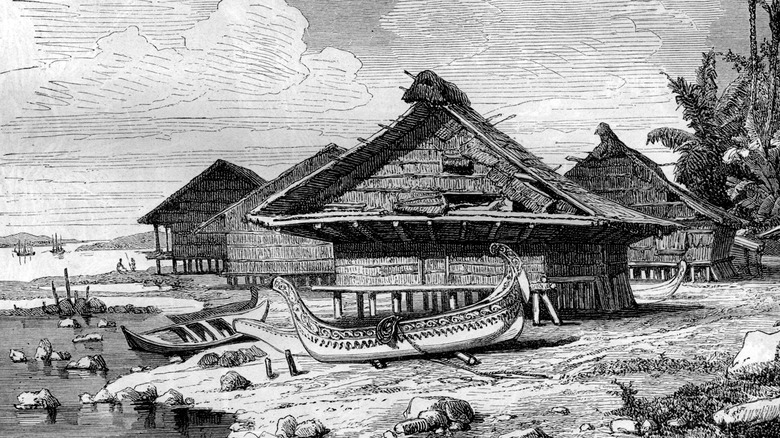

These days, colonialism is largely seen as one of many historical wrongs that need to be righted (if they haven't already been) and understood so that they aren't repeated, but for centuries, particularly in Oceania, it was just a part of life. That was true in Charles Budd Robinson's day, as when he arrived in Indonesia, it was still a Dutch colony as it had been for centuries (via Indonesia Investments), and the archipelago wouldn't fully gain independence until 1949.

As such, the Indonesians were used to Westerners such as Robinson poking about, and according to The Daily Gardener, he was known, liked, and respected around the islands and had even been given the nickname "Doctor Kembang," or "Doctor Flower" by the locals. However, that only applied to populated areas. Out in the more remote islands, things were different, and sometimes Westerners were treated with fear and suspicion. At least, Dr. Robinson was when he set foot on the island of Amboina (now known as Ambon). And that fear and suspicion might have led to his death.

Dr. Robinson's Murder

On December 5, 1913, Charles Budd Robinson set off for the island of Ambon/Amboina "with great enthusiasm," and that was the last any of his colleagues or superiors saw him alive (via Kew Royal Botanical Gardens). A few days later, on December 11, he was reported missing. The assumption, at first, was that he'd gotten lost and/or possibly died in some misfortune, considering his tendency to explore remote areas. However, piecing together clues, it was determined that he'd been murdered. Specifically, locals on the island, including the chief and a number of accomplices, killed him, weighed down his body, and threw him into the ocean.

It was easy to conclude that Robinson was the victim of superstitious and fearful locals, not used to seeing Westerners, particularly one carrying a knife, as Robinson reportedly was. Another report claimed that locals concluded he was a convict — Indonesia had, indeed, been used as a penal colony. However, another theory — and it bears noting that this is nothing more than speculation — is that a language issue and/or a slip of the tongue might have cost Dr. Robinson his life.

Two Similar Malay Words

One of Charles Budd Robinson's colleagues, a Mr. van Diesel, compiled a report of what he believed happened to the botanist, and it includes a fair bit of speculation. Van Diesel came to the conclusion that Robinson was walking toward a village, and he and a young local boy up in a coconut tree spotted each other. The lad was apparently terrified of the European and ran back to the village to warn everyone, and when Robinson arrived at the village, he was met by fearful villagers who then killed him (via Kew Royal Botanical Gardens).

Van Diesel also noted the possibility that language may have come into play. Specifically, perhaps Robinson intended to ask the lad for a "kelapa" – a coconut — but he actually said "kepala," which means "a head." In other words, the boy concluded that Robinson was asking for his head and figured a headhunter was afoot. "I myself had frequently advised him not to go out alone ... because he spoke Malay so poorly," a colleague later lamented (per Kew Royal Botanical Gardens).

Dr. Robinson's Legacy

Though Charles Budd Robinson was murdered by locals on the island of Ambon, it appears that his death there was met with sadness, according to Kew Royal Botanical Gardens. "According to the children of Ambon, who brought him specimens for his herbarium and to whom he was always so kind and friendly, he was incapable of doing any harm. His death has caused general compassion among the population of Ambon," wrote a colleague. Further still, his death was reportedly a "shock" to the rest of Indonesia as well, according to The Daily Gardener.

Fellow botanist Elmer Drew Merrill dedicated his book, "Interpretation of Rumphius's Herbarium Amboinense," to Robinson, according to Global Plants (via JSTOR). Kew Royal Botanical Gardens treats Robinson's death as emblematic of what can go wrong when cultures and languages clash due to colonialism. Similarly, The Daily Gardener points to him as an example of the dangers botanists had to go through — particularly in regard to differences in language and culture — to expand their knowledge of the field.