What Was The Belle Epoque And How Did It Change France?

The late 19th century was a time of extreme societal change in Europe and the U.S. that set the stage for the 20th century. The secularism of the Enlightenment had usurped religious tradition, the factories of the Industrial Revolution had replaced agrarian fields, and the aristocracies of the past fell to democratic representation. And yet, at the same time as society seemed to be making "progress," wealth and class disparity grew, and a general sense of alienation, dehumanization, and unhappiness took root.

England managed to endure the 19th century without a revolution. Public pressure led to greater enfranchisement and humane working conditions even as its monarch, Queen Victoria, watched from the sidelines (via the National Archives). Across the Atlantic, the United States suffered a Civil War and entered its "Gilded Age" (from 1870 to 1900), even as it tackled struggles related to Reconstruction and the era of Jim Crow (via History). And France? From 1871, it passed into its own Gilded Age, the "Belle Époque" — translated as the "Beautiful Age" — which lasted until the beginning of World War I in 1914 (via Thought Co). Unlike other nations, though, 19th-century France had survived four wars on home soil in 80 years. It had not one revolution, but three: in 1789, 1830, and 1848 (via Live Science). The subsequent Franco-Prussian war from 1870 to 1871 left Parisian streets bloodied yet again (via Britannica). It was this battered, tired, and utterly disillusioned Paris that gave birth to the Belle Époque's unique counterculture: cabaret, avant-garde art and literature, an occult obsession, and more.

Excess and despair loomed in post-war Paris

Coming out of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Belle Époque France set about rapidly modernizing, making railroads and telephone lines, and adopting mass-market consumerism. On paper, things looked on the up-and-up. Wages increased for many workers by 50 percent or more, the quality of alcohol and food generally rose, public sanitation greatly improved, and life expectancy increased (via Thought Co).

And yet, France was a fractured society. It never bought into the whole, naïve "progress is good and the future is bright" rhetoric that settled into places like the U.S. — it had simply suffered too much. The "have-nots" in the Belle Époque got plenty of factory jobs and cheap, disposable goods, but the "haves" got much more. France's revolutions finally gave people the republic they'd always wanted, but there was no free, beautiful, participatory society. The bourgeoise regarded the lower classes as moral "degenerates" who would only lead France into societal decay (via Miami Dade College), and those classes despised bourgeoise artifice and superficiality. People in Paris, in particular — a swiftly urbanized setting full of squalor, as the historian Tyler Stovall's "Rise of the Paris Red Belt" depicts – saw nothing but glitz, rot, and hypocrisy (via University of California Press).

And so, the non-bourgeoise expressed their feelings, desires, and despair in the only way possible: art. As the BBC outlined in a 2016 overview, the Belle Époque's counterculture grew in nightclubs and cafes and captured the zeitgeist.

Death, decay, and Symbolism characterized the Belle Époque

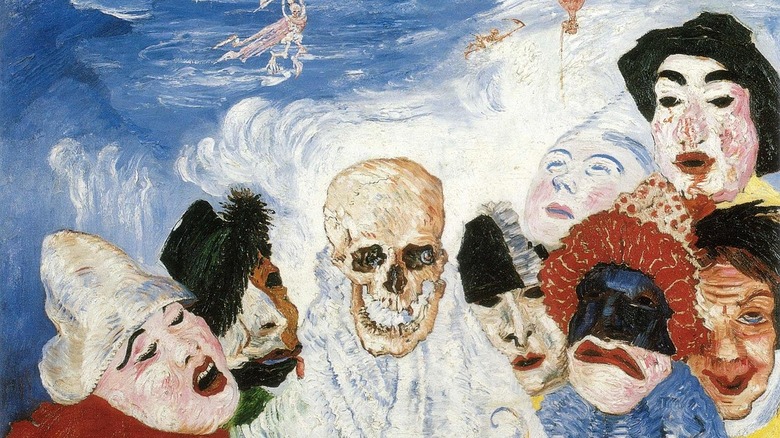

In the mid-19th century, the artistic movement known as Naturalism had been the norm on the European continent. According to a 2021 piece published by My Modern Met, artists pushed for realistic representations of life and emphasized the beauty of the natural world. But at the end of the century, this all sounded absurd and childish — and in order to eschew Naturalism, folks instead sought to rattle the mind free through bizarre and surreal canvases. This paved the way for Symbolism, a kind of "avant-garde" movement which abstracted images further to dig into the heart of reality.

For the uninitiated, Symbolism centered on the presentation of ideas and feelings articulated in symbolic, non-literal ways (via The Art Story). Symbolism also incorporated elements of mysticism, the occult, and preoccupations with death, pain, suffering, evil, sorrow, and all that lovely stuff that few want to think about. It makes sense that this type of art represented the "true face," so to speak, of the wealthy's emptiness and excess, and Parisian society writ large.

Symbolism passed from France to neighboring Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, and even all the way out to Russia. But it was French poet Charles Baudelaire who set the stage and standard for the whole movement with his 1857 poetry collection "Les Fleurs du mal," or "The Flowers of Death" (via Masterclass).

Belle Epoque literature in the decadent depths

As Symbolism gained ground during the Belle Époque, a similar but literary-minded movement — now known as "Decadent" literature — also emerged. Considered a written-word equivalent of Symbolist art, "the Decadents," as their members came to be known, sought to deliberately contravene and countermand the norms of the day (via the British Library). Authors such as Jean Richepin, Jean Lorraine, and Marcel Schwob had counterparts across the English Channel in England's similarly-driven Aesthetic literary movement, known by its herald Oscar Wilde.

Like Symbolist art, Decadent literature tackled deterioration, death, sex, the macabre, the occult, and the taboo head-on, especially as they related to urban decay (via Poem Analysis). Writings produced by the influence of the literary movement often re-paired common phrases to disentangle assumptions. By and large, their patron saint was none other than American horror and mystery maestro Edgar Allen Poe; the aforementioned French poet Charles Baudelaire, who launched Symbolist art in 1857, was also the guy who translated Poe into French for the first time in 1848 (via Springer).

Out of all of them, the most decadent of Decadents was probably Joris-Karl Huysmans. His 1884 novel "À rebours" (or, in English, "Against Nature") — a plotless, pleasure-pursuing vision of growing insanity — set the tone for French Belle Époque writers, per The New Yorker. Such work served to criticize the opulence, indulgence, and excess of the Belle Époque's elites, and also critique the degradations of modernity.

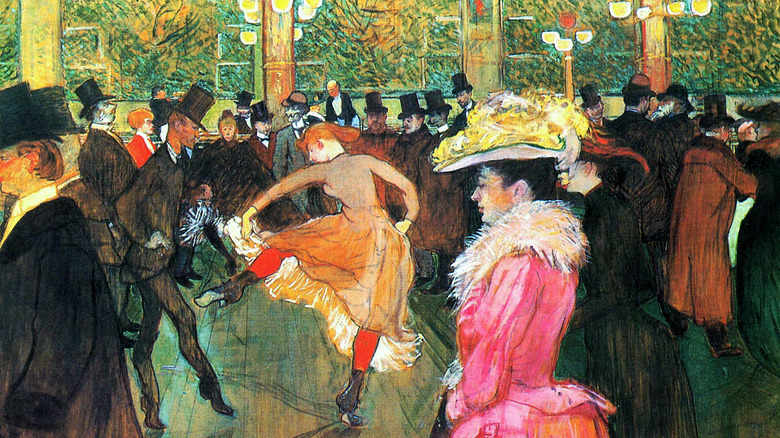

The Belle Epoque saw the rise of cabaret and the fall of salons

All of the artists and writers of the Belle Époque needed places to meet, hang out, talk, drink, watch a show, whatever. As it usually goes, they all tended to congregate at the same cafes, nightclubs, and so forth. Those spaces, in turn, helped foster the culture of the time.

The most famous of these was Le Chat Noir in the Montmartre district of Paris. Located on the north side of the Senne River, the venue became so popular that it necessitated a move to a bigger space in 1885 (via the Rimbaud and Verlaine Foundation). Along the way, it became a hotspot for cabaret, poetry recitals, and popularized "shadow theater," which featured the shadows of puppets projected onto a wall (via the Van Gogh Museum). Le Chat Noir also attracted composers like Erik Satie and Claude Debussy, whose clear, sparse musical arrangements further fueled the overall, ongoing Belle Époque counterculture. Other hotspots included an unnamed first-floor café at the corner of Rue Cujas and Boulevard Saint-Michel frequented by the Hydropathes literary circle (via French Theory).

The vivacity and boldness of such venues began to attract even the aristocracy, especially towards the end of the 19th century. This contributed to the downfall of Parisian salons — high-society social clubs — by decentralizing artistic power (via Cairn). Before then, artists were almost solely dependent on networking at salons to gain notoriety and wealthy patrons.

The Belle Epoque was dripping with the occult

And so we come to the final facet of the Belle Époque: its extreme preoccupation with the occult. Spiritism, seances, mediums, Ouija boards, Satanism, Rosicrucianism, Kabbalah, you name it — The Belle Époque had it, all, per the New Yorker. As with the Belle Epoque's other countercultural movements, this fascination reflected a deep desire to find meaning beyond, and within, the deterioration of the times. If medieval Christianity had led to the secular, scientific, so-called "Enlightenment," and that period led to nothing but spiritual emptiness, hollow glamour, and economic oppression, then there had to be something else, right? As this sense spread throughout modernized nations of the time (as The New Yorker discussed in a 2021 piece on Spiritualism), people turned to non-traditional spiritual truths.

If Baudelaire pre-figured the Belle Époque in an artistic and literary sense, then Éliphas Lévi did the same for its spiritual identity. Lévi's 1861 book "Transcendental Magic: Its Doctrine and Ritual" set the course for countercultural religious inquiry during the Belle Époque and beyond. It acted as a catch-all for magical knowledge, lore, and heritages (via Google Books). Even the book's cover, Lévi's own hand-drawn Baphomet image, amalgamates various sacred symbols, per Britannica.

As the world moved into the early 20th century, World War I broke out and officially ended the Belle Époque. The period might have faded, but its angst and resentment left behind a singularly unique counterculture that contains lessons more than applicable to the modern day.