World Leaders Who Suffered The Most Tragic Deaths

These days, when a U.S. president dies, it is usually out of office well after their tenure has ended. In fact, no U.S. president has died in office since 1963. Generally, the most prominent world leaders tend to die out of office, and relatively few make the headlines for premature or tragic deaths. But not too long ago, leaders used to die a bit more often. In the days of more dangerous air travel and less advanced medicine, a leader that went on a plane or got sick risked dying suddenly. Furthermore, the social ferment and unrest of the 20th century — particularly the Cold War — provided a perfect environment for a handful of leaders to die violent deaths at the hands of their ideological opponents.

When a leader dies unexpectedly — as tragic deaths tend to be — it has greater consequences because a country is suddenly left leaderless with a window for political unrest. Thus it is unsurprising that most leaders mentioned here left behind countries that soon descended into varying stages of turmoil and even all-out genocide. Here are some world leaders whose deaths and their aftermaths were particularly tragic.

Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto, the first female Pakistani prime minister, had a checkered career (via Britannica). She became Pakistan's first civilian government prime minister in 1988 after the end of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq's military regime but fell out of favor with the Pakistani military government of President Pervez Musharraf and went into exile. Her husband, meanwhile, went to prison. But she was finally able to return to Pakistan in 2007 after Musharraf granted amnesty.

Upon return to Pakistan, it became clear that not everyone in the country's power structure wanted her back. Per the BBC, as she had just arrived from exile, a suicide bomber blew himself up, missing her but killing over 150 people. The second time, the assassins were successful. According to a second BBC report, a suicide bomber shot her twice and detonated himself near her motorcade as she was leaving an election rally in Rawalpindi, killing her and 20 others. Perhaps most tragically, the suicide bomber was only 15.

Bhutto's death triggered mourning, protests, and rioting in Pakistan, but no one took responsibility immediately. There was talk (per BBC) in Pakistan that government insiders orchestrated the murder while Musharraf's government ran cover, while Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence blamed Osama bin Laden (per First Post). Now, the al-Qaeda theory is rife with controversy because even Bhutto would not have believed it. In an interview with Al-Jazeera English in June 2007, Bhutto claimed that bin Laden was dead. But given the enemies she had in Pakistan, an assassination by government elements in cooperation with militants — al-Qaeda or otherwise — is perfectly plausible.

John F. Kennedy

President John F. Kennedy was widely viewed as representative of America's golden years of the 1950s and early '60s. According to Mary Washington University, his wealth, Harvard degree, charm, looks, war hero status, and glamorous wife all lent a fairytale air to the Kennedy White House (aka Camelot). As Harvard notes, Kennedy exuded optimism through his commitment to peace, promotion of intellectual life, and dedication to space exploration (via NASA). But the dream ended on November 22, 1963, when Kennedy was killed during a campaign stop in Dallas. CBS News referred to the event as "the day America lost its innocence" as the symbol of Camelot glamor slumped into his wife's arms on national TV.

According to the JFK Library, Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested but soon murdered by the shady, mob-linked Chicagoan named Jack Ruby. According to the subsequent Warren Commission (via National Archives), Oswald acted alone. But the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded in 1978 that Kennedy had been hit by at least two gunmen, making the event a conspiracy. Oswald's record as a CIA asset (via Hood College) fueled suspicion. In 1971, per a 1994 news report, conspiracy advocates were possibly vindicated when a man named Loy Factor claimed to have been hired as a gunman along with Oswald and at least two others. Factor claimed that conspirators paid him to help shoot Kennedy, but he said he never fired.

Kennedy's death ended the optimism of the 50s and gave way to the turbulent '60s, which saw the rise of the civil rights and counterculture movements, sexual revolution, and protests over Vietnam.

Nicholas II

Nicholas II, the last Czar of Russia, met a particularly horrific end. According to Britannica, the last czar of Russia abdicated during the 1917 Russian Revolution. But he probably did not deserve the treatment — he was hardly a tyrant (by the time's standards). According to the Alexander Palace Time Machine, the czar was devoted to his family, his people, and his job.

Despite his abdication and desire to leave Russia, the Bolsheviks decided to execute the imperial family. According to Bolshevik executioner Yakov Yurovsky himself (via the Alexander Palace), the Bolsheviks marched the czar, his four daughters, his son Alexei, his servants, and Empress Alexandra into the basement and lined them up. Yurovsky quickly read off the death sentence and shot the czar without warning; additional gunmen finished off the rest. The girls and the empress were shot in the head because their valuables sewn into their clothes protected them from bullets and bayonets. The assassins then burned the bodies and dumped them in shallow graves.

According to Baltimore's Transfiguration of our Lord Russian Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Makary of Moscow claimed to have seen Nicholas speaking with Jesus Christ. In the vision, Christ ordered the czar to drink a sweet cup, while the bitter chalice was reserved for Russia. Instead, the czar took the bitter cup and Russia's sins upon himself, becoming a martyr for his people and church. Once the USSR fell, the czar's remains returned to St. Petersburg in 1998, where he was given a state funeral and properly laid to rest.

Haile Selassie

According to The New York Times, Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie was an accomplished man. He steered Ethiopia through Italian occupation, World War II, modernization, and the abolition of slavery. Yet, he was overthrown in a 1974 coup by the Soviet-backed communist Derg regime. In 1975, The New York Times reported that the emperor — heir to the 3,000-year-old Ethiopian dynasty that traced its ancestry back to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba — died in his sleep while in Derg custody.

As it turned out, the world media was fed a lie by the communist regime. In 1994, Ethiopia charged a handful of former Derg officials in absentia for 2,000 murders and disappearances. The Washington Post reported that the charges rested on damning documents revealed after the regime's fall in 1991. As it turned out, Derg leader Mengistu Haile Mariam had ordered the 83-year-old emperor strangled in his sleep — or according to some other accounts, smothered with a pillow. Either way, Selassie was in no condition to offer any resistance.

Today, as the LSE notes, Selassie is seen as an African icon and an inspiration to people of African descent around the world. According to Jamaica's Ethiopian Orthodox Church (EOC), he even sent Ethiopian Orthodox missionaries to Jamaica at the request of the Rastafarians. Selassie touched at least one famous Rastafarian reggae singer named Bob Marley. According to CNW, Marey was baptized into the EOC with the name Berhane Selassie in honor of the man he had once considered the messiah.

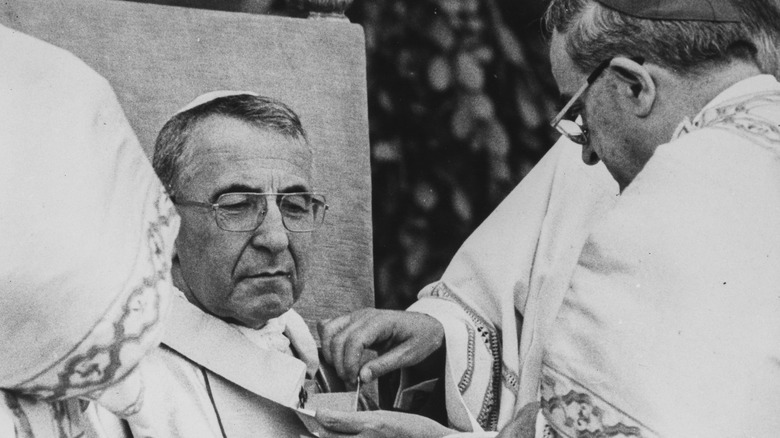

Pope John Paul I

Pope John Paul I was elected in 1978 on the heels of the controversial Pope Paul VI and the Second Vatican Council, which made a number of changes to the Catholic Church to better confront the modern world. But after a 33-day papacy, tragedy struck. According to Stefania Falasca's "The September Pope," two nuns found the pope sitting up in his bedroom dead. So what happened?

According to Crux Now, the pope died of a heart attack. But inconsistent statements from the pope's Irish secretary Bishop John Magee triggered skepticism that the pope had been murdered (via The Irish Times). Although Crux Now and the Vatican reject the murder hypothesis, NYC mobster Anthony Raimondi claimed in his book "When the Bullet Hits the Bone" that Cardinal Paul Marcinkus had personally poisoned the pope to avoid discovery of stock fraud and corruption involving the highest levels of Vatican bureaucracy and clergy (per the New York Post). As the lookout, Raimondi was a little less guilty, hoping that taking an inactive part in the pope's murder would spare him a "one-way ticket to hell."

John Paul I's death — regardless of the cause — was tragic not only for the brevity of his tenure but also because the "smiling pope," as he was known, was a truly beloved figure who had dedicated his tenure as Patriarch of Venice to the service of the poor. His death cleared the way for the election of John Paul II, who played a role in the fall of communism in Eastern Europe.

Lech Kaczynski

Joining Pope John Paul I in the column of uncertain but tragic deaths is former Polish President Lech Kaczynski. According to Poland's TVP World, the former president of Poland was involved with the anti-communist Solidarity movement as an advisor during the Gdansk shipyard strike of 1980. He soon became Lech Walesa's right-hand man and engineered the Solidarity leader's election as president in Poland's first post-communist democratic elections in 1990. Eventually, Kaczynski became president himself in 2005 as part of the conservative nationalist PiS Party. But his dedication to securing American and NATO support for Poland's security set him on a crash course with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

2010 was the 70th anniversary of the Katyn Forest Massacre, wherein the Soviet NKVD liquidated Poland's elite and blamed the Nazis for it (per the National Archives). Putin snubbed Kaczynski and invited his old political opponent Donald Tusk to a commemoration of the event. Kaczynski decided to attend a separate commemoration in the Russian city of Smolensk, but he never reached his destination. According to EuroNews, his plane went down in thick fog, and the tragedy was ruled an accident. But since it happened on Putin's watch, theories quickly emerged that Russia was involved in a state-level assassination. After three investigations, Poland concluded that Russia had tampered with the plane and covered it up by refusing to hand over the remains for investigation. So far, the case is unresolved but continues to contribute to tensions between Poland and Russia 12 years later.

Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin famously was the Israeli prime minister that signed the Oslo Accords with Palestinian PLO leader Yasser Arafat in 1993 and 1995 (per Britannica). The treaties established Palestinian self-government in the Gaza Strip and West Bank on the road to a two-state solution. As noted in the Journal of Palestine Studies, the accords were not perfect, and Palestinian militant Islamist group Hamas and other extremist organizations rejected them. Nevertheless, they were hailed as a step in the right direction, and with Rabin at the head, Israel had a leader that whom the PLO might be willing to negotiate with.

Sadly, Rabin was shot and killed at a 1995 peace rally in what was called "Israel's Kennedy Assassination" (via JFK Library). One million mourners attended his funeral in Tel Aviv (via CNN), where the Israeli leader was eulogized as a "soldier for peace." According to CNN, Yigal Amir, a Jewish law student and opponent of concessions to the Palestinians, shot Rabin on "orders from God." But numerous theories of a larger conspiracy involving complicity from Israeli government organizations have circulated in Israel since 1995.

Rabin's death was made more tragic by the lingering question: What if he had lived? Israeli journalist Nahum Barnea (via NPR) argued that it is difficult to ascertain the outcome of such a volatile situation. However, she noted that Rabin had the respect of most of the Israeli political establishment, suggesting that had he lived, Israel would at least be more united and better equipped to deal with the Palestinian crisis than it is in its divided state today.

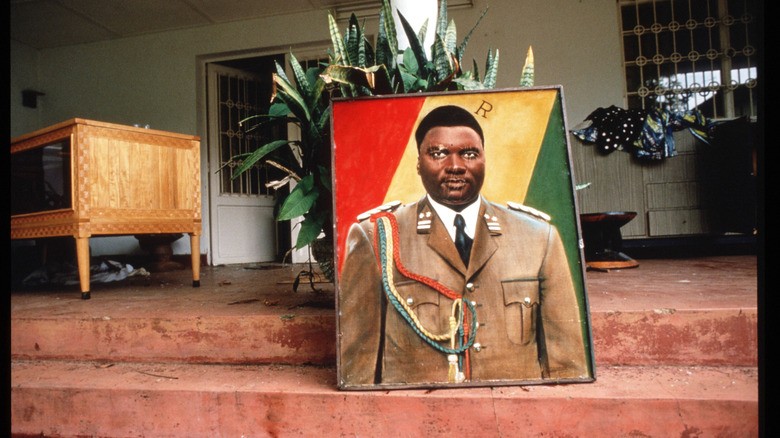

Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira

Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira were the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi respectively. According to the University of Leiden, both men were members of the Hutu ethnic group and were known as moderates in their respective countries. Habyarimana, in particular, had courted Rwanda's Tutsi minority to work out a potential power-sharing agreement. But in 1994, political opponents — it is unclear who — shot down the plane carrying both presidents.

The assassination is tragic because it ignited the Rwandan Genocide against ethnic Tutsis by Hutus. Now, according to the BBC, Tutsis had dominated the Rwandan elite — including the country's former monarchy — before 1959 at the Hutu majority's expense. So when the Tutsi-dominated rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) was blamed for shooting down President Habyarimana's plane, tensions exploded. By the time the horror was over, nearly 1 million people were dead, numerous women had been forced into sex slavery, and 2 million became refugees (via United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees).

It is still unknown who triggered the genocide. Per the BBC, a French investigation concluded that RPF leader and later president of Rwanda Paul Kagame had ordered the hit. Kagame denied all wrongdoing and claimed France's Hutu allies in Rwanda were responsible. Either way, all investigations have been marred with accusations of political bias. Since the RPF's leaders ultimately took power in the civil war, it is unlikely it will ever take responsibility if its forces were responsible for downing the plane.

Boris Trajkovski

Boris Trajkovski became president of the small Republic of North Macedonia (formerly FYROM) in 1999. According to Christianity Today, the Methodist pastor-turned-politician began an anti-corruption campaign that saw numerous government officials removed from their posts. After an Albanian insurgency broke out in 2001, Trajkovski fought the rebels — many of whom had come from neighboring Kosovo — and courted NATO assistance to ensure that the Albanian rebels did not find sympathy with Macedonia's Albanians or with the Kosovar refugees that had sought shelter during their own conflict with Yugoslavia. Macedonia, already an ethnically-diverse state, did not need a civil war. According to RFERL, the parties agreed to a NATO-brokered Ohrid Accord, which provided Macedonia's Albanians autonomy where they were the majority.

So far, Macedonia, having avoided a civil war, seemed to be on the right path, and Trajkovski was prominently involved in the process every step of the way (per Balkan Insight). But his tenure was cut short when his plane crashed over the Bosnian city of Mostar. Despite claims that the plane had been shot down, investigations revealed that the aircraft was not in the condition to fly, and the flight crew was not prepared to deal with the foggy weather. In other words, the flight should have never taken off. However, Trajkovski's legacy — the Ohrid Accord — has held. Despite occasional tensions between Albanians and Macedonians, the absence of a new insurgency suggests that his work was not in vain.

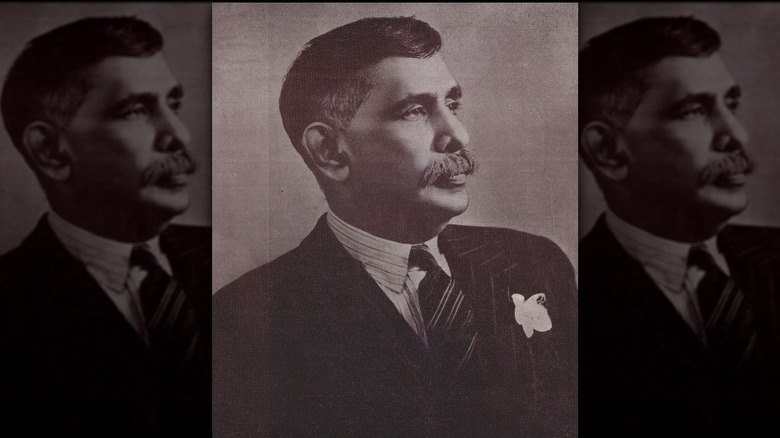

Ramon Magsaysay

Ramon Magsaysay was sworn in amidst pomp and ceremony as president of the Republic of the Philippines in 1954 (per a British 1954 newsreel). He promised to reform and extend the benefits of government to all 20 million citizens of the archipelago. Of humble origins, this larger-than-life president was considered a man of the people and an outsider to Manila's political class (via Pacific Historical Review). But he was also accused of being a CIA puppet. The truth, as usual, lay somewhere in between. While he certainly courted the United States for aid, he had to balance American interests, the interest of the Philippines' traditional elite (e.g., planters, the Catholic Church, and industrialists), and the masses.

Magsaysay won the 1953 election with the backing of this broad coalition and promised to ram through land reform and break the "Communist-led peasant uprising" known as the Huks (via Britannica). He was known for being incorruptible, and perhaps this unwillingness to get his hands dirty contributed to his political opponents stymying his reform attempts. Unfortunately for his supporters, Magsaysay's frustrated but still promising tenure was cut short in 1957 when his plane crashed. According to the Kahimyang Project, the president's plane went down on a return flight to Manila from the southern island of Cebu. The plane crashed into a tree and killed all but one passenger. A whopping 2 million people attended his funeral — a sign of a much-loved leader whose tenure had promised so much.

George VI

According to History Extra, King George VI — the father of Elizabeth II — met his end in his sleep on February 6, 1952. The announcement shocked Britain and the world. The king was only 56 and left behind a 25-year old daughter whom many people believed was incapable of managing the monarchy in the modern world.

Elizabeth was the most affected by the death, in part because it was so unexpected and unnecessary. Now, according to Vanity Fair, George should never have been king. The awkward prince always lived in the shadow of his charming and handsome brother Edward, and though he became King Edward VIII in 1936, he abdicated the throne to marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson. Thus, George ascended to the throne of Great Britain in an increasingly dangerous Europe on the verge of war. To make matters worse, Edward began socializing with Britain's soon-to-be enemies — men such as Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.

After surviving the blitz and being on the winning side in World War II, Edward returned from the Caribbean, asking for George to accept his wife as part of the royal family. The entire ordeal, coupled with the stress of the war, broke George. The king died in his sleep, and Elizabeth blamed her uncle for cutting her father's life short with his selfishness.

Stephen Senanayake

The United Kingdom's National Portrait Gallery calls Stephen Senanayake the "Father of the Nation." In fact, this Sinhalese politician was key in establishing the independent nation of Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) as the British Empire came apart after World War II and became its first prime minister. While much of Sri Lanka praised him for his role in independence, he was a controversial figure among Sri Lanka's Tamil minority. According to historian Sachi Sri Kantha, they accused the leader of stoking ethnic tensions by settling non-Tamils in Tamil lands (via Illankai Tamil Sangam). In fact, according to The Indian Express, he helped ram through a bill that left Tamils stateless.

Whatever his reputation, Senanayake met his end in a painful manner. According to the Sunday Times, the man was an avid horseman. Even at 68, he could hold his own in the saddle. After about a mile at gallop, the prime minister suddenly fell off his horse and tumbled onto his side. He was pronounced dead after 32 hours unconscious. Interestingly, it was probably not the fall itself that killed Senanayake — doctors believed that he had suffered a stroke. Per the University of Central Arkansas, his son Dudley took over. He was, however, unable to keep public confidence, and Sri Lanka endured civil war, political unrest, and ethnic conflict that definitively ended in 2011.