The Untold Truth Of The Connecticut Witch Trials

The following article contains descriptions of torture that are graphic in nature.

The most famous witch trials in America are those in Salem, Massachusetts. But more than 40 years before the Salem Witch Trials, there were people being executed in Connecticut because their friends and neighbors believed they were working for the devil.

The total number of people charged with witchcraft in Connecticut is unknown, but experts estimate that it was more than 35. As stated by Time, nine women were hanged as witches, and two men were hanged alongside their wives. As explained in "Connecticut WItch Trials: The First Panic of the New World," first came the Hartford Witch Panic (1662-63), which began with a child's death and the story of a possessed woman. After 1663, there was a period in which the panic calmed, and fears of witchcraft subsided, thanks to the efforts of Governor John Winthrop, who was skeptical about witches. Decades later, however, the Fairfield Witch Panic of 1692 sparked around a teenager experiencing mysterious fits.

Stories about witches were bizarre, terrifying, and apocalyptic

Amongst the New England colony Puritans, it was a common belief that the end of days was coming, and soon. As explained in "American Apocalypse," this was both an exhilarating and terrifying idea since, along with salvation, they expected a period of horrors and a "day of doom." The Puritans believed that their communities would have a special role to play in the coming battle. "The Wonders of the Invisible World" reflected the belief that the devil was using all kinds of diabolical strategies to tempt them away from God and would only become more dangerous as the Second Coming approached.

It was believed that witches were among Satan's most deadly weapons. As stated in "Connecticut Witch Trials: The First Panic in the New World," witches were people who had agreed to sign the devil's book, swearing their allegiance to Satan. Puritans believed that the devil could take the shape of his witch servants to spread havoc on earth, and witches were thought to be cannibals who killed infants. Their pact with the devil was supposed to give them all kinds of terrifying powers, including demonic familiars in the shape of animals like rats and snakes (which they fed from secret nipples) and the ability to summon disease, blights, or droughts, and attack people in their dreams. Many described feeling pain or choking from witch attacks, and some claimed witches could make men's genitals vanish.

It started with a tragedy

Hartford, Connecticut was the site of the first witch execution in the American colonies. As stated by History, a woman named Alse Young was hanged in 1647. It was another 15 years before Hartford had another witch trial — but this one sparked a deadly panic.

In 1642, one family's desperation to have someone to blame for their child's fatal illness led to seven witch trials and four executions. As described in "Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England," 8-year-old Elizabeth Kelly had been a healthy child until she suddenly came down with a mysterious illness (likely pneumonia and sepsis). A neighbor, known as Goodwife Ayres, brought some hot soup to share with Elizabeth. Soon after, the child started complaining about a stomach ache. The parents feared that the soup that Elizabeth and Goodwife Ayres had eaten together was too hot. The following day, Elizabeth seemed much better, but she got sicker again overnight. Later, the parents would testify that before her death, she screamed out repeatedly that she was being tormented by Goodwife Ayers.

The Kellys came to believe that Goodwife Ayers had used witchcraft to kill their daughter. The panic spread.

The first forensic autopsy was performed looking for witchcraft

The distraught parents of Elizabeth Kelly became suspicious of the way that her body looked after death. As detailed in "Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England," Goodwife Ayres, Goodwife Whaples, and Rebecca Greensmith came to help the Kellys after the child had died. At the parents' request, Goodwife Ayres wiped the child's mouth and attempted to pull up her sleeves. In doing so, they discovered that the child had bruises on her shoulders, right side, and stomach, as well as redness on her cheek. In modern forensic pathology, there are multiple explanations for marks similar to the ones described — from post-mortem bruising to the natural settling of blood after death known as livor mortis — but to the Kellys, these marks were suspicious. They noted that the redness on Elizabeth's cheek was on the side that Goodwife Ayres was on and began to believe this was a sign of her guilt.

The body was officially examined in what has been referred to as the earliest documented forensic autopsy. The autopsy report determined that there were several unusual things about the body, which they dubbed "preternatural." These included the discoloration noticed by the Kellys, a lack of stiffness about the body (which is typical after several hours), and the fact that some blood had not clotted.

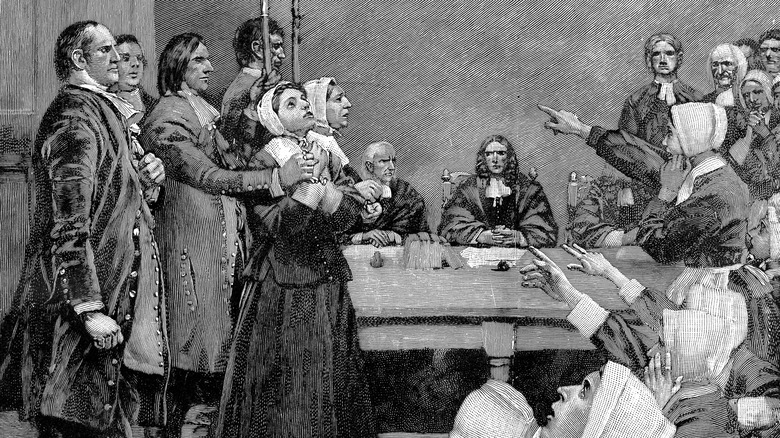

Witchcraft was a crime

There were 12 capital crimes at the time of the trials, and one of them was witchcraft. It was also considered a special type of crime that didn't have to abide by typical procedures for convicting an accused person. They believed that the devil might deceive people into thinking an innocent person was a witch — but God would prevent more than one person from being tricked. Cases with multiple accusers were therefore considered more legitimate. "The skepticism of the Connecticut Court, then, was embedded in a very particular culture," explained historian Alison Games (via the Connecticut Judicial Branch), "one that was concerned about legal practices and the use of evidence but that also based its conclusions on assumptions about what God or Satan would — or could — do."

As explained by Time, no evidence was needed to begin a witchcraft trial against someone. If one person accused someone, that was enough, even if that person was known to have a grudge against the person they claimed was a witch. Their accusations didn't have to be based on things that physically happened, either. As stated by the state of Connecticut judicial branch, the courts accepted "spectral evidence." This included having visions about the accused or seeing them do witchcraft in a dream. Someone could also be charged for a crime someone else committed. In one instance, when a man accidentally shot someone, a woman named Lydia Gilbert was hanged for witchcraft. It was believed that she caused the accident using magic.

The fate of accused witches varied

While witchcraft was explicitly punishable by death, not everyone who was accused was killed. Of the approximately three dozen people accused of witchcraft, 11 were executed by hanging. Many were subjected to painful and humiliating tortures prior to their deaths. But as noted by Time, that doesn't mean the rest were declared innocent and allowed to go free.

Goodwife Ayres and her husband were forced to flee, leaving everything behind, including their 8-year-old son. As noted by the Hartford Courant, if they had stayed, they would likely have been killed. One woman named Katharine Harrison was also forced to leave her home. Harrison had read a book about astrology and told some of her coworkers their fortunes. When one of her predictions came true, she was accused of witchcraft. Already disliked by her neighbors, Harrison was at risk, so she was allowed to pay a fine and was essentially banished.

John Winthrop Jr., Connecticut's governor and chief magistrate, eventually gained the power to pardon people accused of witchcraft and made it more difficult to convict someone on witchcraft charges.

Some people were more likely to be accused than others

Accusations often took place after tragedies that had no actual culprit (such as droughts that destroyed crops or unknown medical conditions), and the accused witch became a scapegoat for the community. Despite these accused witches having no real connection to the tragic events that spurred the people of Connecticut to go witch hunting, some people were more likely to be accused of witchcraft than others.

As described by the Wethersfield Historical Society, the vast majority of those accused were viewed as strange by the community already. Many were poor, had previously been convicted of petty crimes, or just didn't fit in. Often they were women, likely because it was believed that women were more susceptible to be taken in by temptations from the devil. Women may even have been more likely to confess to witchcraft because of this. As explained by historian Elizabeth Reis, because women believed that they were at risk of being tempted by Satan, they were more likely to believe that anything they did wrong, no matter how small, meant that they were allying themselves with the devil.

The first witchcraft confession

In Salem, those who plead guilty were often spared, while those who insisted on their innocence were often put to death, but in Connecticut, confessing to witchcraft was not always the surest path to survival. The first confession from an accused witch in the American colonies came from Mary Johnson. She was convinced to confess without trial, and this confession had a tremendous impact on the witch panic that would come after. It also led to her death.

Cotton Mather recorded the details of Johnson's testimony. She testified that she had been unhappy, and the devil came to help her. Johnson was a servant, and the devil purportedly worked to keep her from being in trouble. For instance, she once got in trouble for leaving ashes in the hearth, so the devil kept it clean for her. Johnson confessed to "uncleanness" or intimate relationships with both men and devils. Most dramatically, she confessed to killing an unnamed child — but as stated in "Connecticut Witch Trials," she was likely referring to terminating a pregnancy.

They believed a woman was possessed

Some have traced the start of the Hartford Witch Hunt to another case at around the same time that Elizabeth Kelly's parents were accusing Goodwife Ayres: the mysterious illness of Ann Cole. Like Elizabeth Kelly, it is likely that Ann Cole was suffering from a real condition. At the time, however, her symptoms were attributed to "diabolic possession."

As described in "Witch-Hunting in Seventeenth-Century New England," Ann Cole was known to be a very pious person. She began experiencing fits or seizures and claimed that witches were attacking her. During her fits, she began naming some of her neighbors as witches. Ann Cole was mostly incoherent during her episodes and afterward claimed that she didn't remember anything that she said. As stated in "Witchcraft," she claimed that there was a coven of witches working in Hartford. She accused several women, including Elizabeth Seager and the widow Rebecca Greensmith — one of the women who had helped the Kellys to care for their daughter Elizabeth as she was dying.

They were influenced by the Witchfinder General

The most famous witch hunter was undoubtedly Matthew Hopkins. Although he never set foot in the American colonies, the English witchfinder was partially responsible for the way that witches were hunted in Connecticut.

As described by History, Matthew Hopkins made his living as the Witchfinder General — coming into communities and using his own method for rooting out witches. Along with his partner John Stearne, Hopkins would spread fear of witches, accuse members of the community of being witches, torture them into confessing, execute them, and then collect payment from their neighbors. He wrote up this method in a book called "A Discovery of Witches" in order to make himself seem more legitimate. According to Historic UK, he was personally responsible for the deaths of more than 300 women and became extremely wealthy.

This method was a profound influence on Connecticut's witch trials, and they adopted many of his methods of testing and identifying witches — which were essentially tortures designed to get confessions.

There were tests for witchcraft

Accused witches were in danger of being forced out of their homes or executed if they were found guilty, but things were not any better for accused witches before their convictions. The methods of determining if a person was a witch or not were often excruciating. Thanks to the fame of the Witchfinder General, there were some horrendous tortures that were accepted as methods of determining who was guilty of witchcraft. The most well known of these is probably the water test. As described in the Stamford Advocate, it was believed that witches always floated in water. In order to test accused witches, they would tie their hands and feet and throw them into the water. If they sank, they were considered innocent (but they might also drown).

Matthew Hopkins used a number of torture and interrogation techniques that were copied and adapted in Connecticut. As stated by History, Hopkins kept the abused sleep-deprived, preventing them from eating or drinking, forced them to stand in the same position for long periods of time, and made them walk nonstop until they agreed to confess. He would also search the bodies of accused witches for devil's marks that he would stab with pins. He would also slide knives across their skin, claiming that if they didn't bleed they were witches — but the knives were not sharpened.

Some people wouldn't turn on their neighbors

One of the tests for determining if someone was a witch was to search their body for "witch marks." As described in "Connecticut Witch Trials," it was believed that when a person became a witch, they gained an extra nipple, which their demonic familiar servant would use to feed. In practice, this was very difficult to disprove since anything from a mole to a flea bite might be considered evidence that the accused was a witch.

The presence of these marks was used to convict and ultimately hang a woman called Goodwife Knapp. As stated by the Hartford Courant, a committee of women were charged with searching her body until they found the evidence. They tried to convince Goodwife Knapp to call out others in the community as witches, even telling her that her neighbor, Mary Staples, had turned on her and testified that she was a witch. Knapp continued to swear her innocence and never accused anyone else of witchcraft, even at her execution.

Before Knapp was set to be executed, Staples attempted to take back her testimony, swearing that Knapp was not a witch. After Knapp was executed, Staples ran to the body and began tearing its clothes off, crying that there were no witch marks and that Knapp had no more nipples than anyone else. Some of the women from the committee attempted to bring witchcraft accusations against Staples as well, but she was never charged.

Another panic flared around a woman named Katherine Branch

Ann Cole was not the only accuser who seemed to be suffering the effects of an actual medical condition that was mistaken for a witch attack. Unfortunately, medical science was not yet advanced enough to find answers. As with the autopsy performed on Elizabeth Kelly, attempts were often made to determine if there was a natural cause — they just weren't able to find them.

In 1692, a servant named Katherine Branch was out picking herbs when she suddenly collapsed, writhing on the ground. As described in Stamford Advocate, she would cry and scream incoherently during these events, which happened periodically for several weeks. A midwife was called to determine what was wrong with Branch. After an initial examination, the midwife believed that Branch was ill and attempted to treat her condition. Unfortunately, the usual treatment was bloodletting, which had no effect on Branch's condition. When she didn't get better, the midwife assumed Branch must have been bewitched.

Branch began to tell incredible stories about shapeshifters and talking cats. She would go on to formally accuse two women of witchcraft (and mention several more).

Not everyone believed in witches

Physician and alchemist governor John Winthrop Jr. was largely responsible for keeping the witchcraft hysteria from spreading as much as it did in other colonies and ultimately ending the trials. As stated in "Connecticut Witch Trials," while Winthrop likely believed in witches, he usually looked for natural explanations over witchcraft. It is believed that the death of Elizabeth Kelly sparked panic partially because Winthrop was in England at the time and wasn't there to calm the hysteria. While they tried and executed witches, the people of Connecticut could also be skeptical. This is particularly evident in the case of Katherine Branch.

"The villagers did not just assume blindly that just because Kate Branch was accusing women of witchcraft, they were guilty," colonial witchcraft expert Richard Godbeer told the Stamford Advocate. There were violent tests performed to prove someone was a witch, but some skeptical citizens also performed tests to see if the accusers were actually bewitched. There was a belief that if a sword was held over the head of a bewitched person, they would not be able to stop laughing. One man tested Branch's accusations by holding a sword over her head and determined that when she knew it was there, she would laugh, but when she wasn't aware there was a sword over her head, she was unaffected. Even after one of the women Branch accused failed the water test by floating, many continued to question her guilt.

The victims are remembered

While the Connecticut witch trials have never been as famous as the trials in Salem, those who were falsely accused of witchcraft in the southern New England state are still remembered.

Many are familiar with the Connecticut witch trials because of the popular children's book "The Witch of Blackbird Pond." The book features actual historical figures from the time and takes place in Wethersfield, where many of the trials actually took place. As stated by the Wethersfield Historical Society, however, the book is a work of fiction and does change many historical elements to suit the narrative. The most obvious of these is that the falsely accused woman depicted is targeted because she was a Quaker, and in reality, no Quakers were ever accused of witchcraft in Connecticut.

In 2017, several descendants of the accused and their supporters campaigned for awareness of what had happened to accused witches. According to the Hartford Courant, attempts were made to secure posthumous pardons from Queen Elizabeth II (as the trials had taken place when Connecticut was a colony), but it was determined that there were too few records to reopen the case. However, in the town of Windsor, a ceremony was held reading out the names of those who had been killed, and a resolution was passed to absolve the women who had been hanged there.