The Macabre Truth About Books Bound In Human Skin

For the vast majority of people, the idea of anything made out of human remains is a serious taboo. Sure, different individuals, families, and cultures may lay out different rules for how to dispose of human remains. You may know of someone who keeps a loved one's cremated remains in their home, for instance, or you could already be familiar with the Victorian practice of making memorial jewelry out of the deceased's hair. But, while objects like urns and bracelets are meant to memorialize a person who's now gone, they're hardly presented as curiosities or sideshows. Contrast these loving, sometimes solemn remembrances with tales of far less respectful ways of dealing with human remains. For example, there are the terrible stories of atrocities committed during the Holocaust, including soap and lampshades made from human fat and skin, respectively. (It's worth noting that for all the awful things perpetrated by the Nazis, these particular rumors are highly controversial and aren't fully substantiated, says Haaretz.)

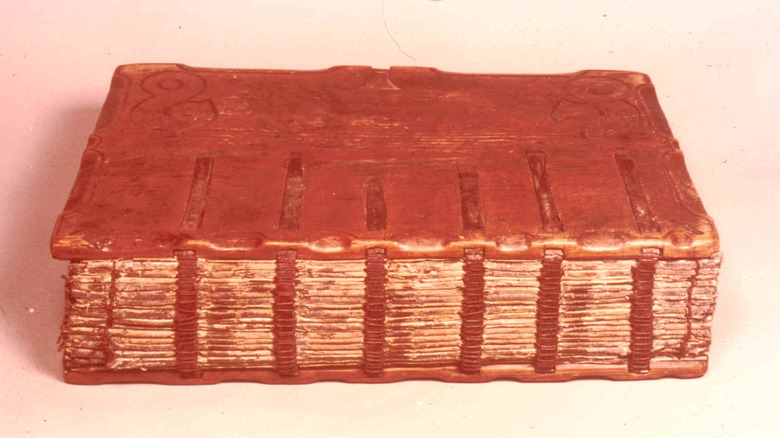

Within this unsettling world, there is one object that seems to hold particular interest: books bound in human skin. This practice, known in academic circles as anthropodermic bibliopegy, may sound too gruesome to really be true (via the Anthropodermic Book Project). Yet both reliable historic records and scientific testing prove that, sometimes, the rumors really are true. Here's the macabre truth about books bound in human skin.

Myths abound when it comes to human skin objects

When it comes to objects made from human skin, people tend to ask very uncomfortable questions. Who did that skin come from? Who did the obtaining? Are they still at large?

Since the presence of human skin objects gives people the heebie-jeebies, it's also understandable that quite a few myths have sprung up around them, books included. But, though these stories may be shocking, it's hard to verify them. Take, for instance, the human skin lampshade — a common story used to illustrate the horrors of the Holocaust and the Nazis' inhumanity. Yet, as The New York Times notes, there are no confirmed widespread cases of such lampshades. Even one that was previously "proven" to stand as a macabre example was later retested and shown to be made out of cowhide (via Lake Superior Magazine).

Other far older tales are likewise impossible to prove. As per "Bibliologia Comica," ancients reportedly flayed people as punishment for sacrilege or to create war trophies, among other motivations. In medieval Europe, objects made from human skin, such as shoes and belts, were said to lend magical and protective powers to the wearer. Icelandic sorcery supposedly helped some especially dedicated magicians create a pair of "necropants" from the remains of a deceased friend (via Atlas Obscura). Supposedly, said pants would produce endless riches, though the only known "example" is actually a reproduction, and it's unlikely that anyone really tried to make a pair, as Iceland Magazine notes.

Early references to human skin books appear in the Middle Ages

According to "Bibliologia Comica," stories about human skin books go as far back as medieval Europe. The stories, practically all unverified, maintain that some collections held books that had been covered in flayed and preserved human skin. However, it's critical to note that no one's uncovered these almost mythical volumes, least of all offered them up for scientific testing to confirm their origin.

Some other early accounts of human skin books arise from the French Revolution. This 18th-century uprising against the ancient regime of France's monarchy was awash in blood and chaos. During the worst days of the revolution, it must have seemed as if people were being beheaded left and right. Certainly, if both the king and queen of France could lose their heads, then anyone might be subject to the same fate. What's more, beyond the undeniable public horror of the guillotine, there were whispers of even worse things that went on behind closed doors. Per Lapham's Quarterly, some claimed to have seen gory workshops wherein corpses of the condemned were processed for, among other things, their skin. Somewhere, perhaps in a revolutionary's private collection, there was a book bound in the hide of an enemy of the republic. Yet again, no direct evidence of these shops has surfaced, leading many to believe that they are instead the product of frightened rumor-mongering during an especially violent place and time in human history.

The motivations behind making these books are complicated

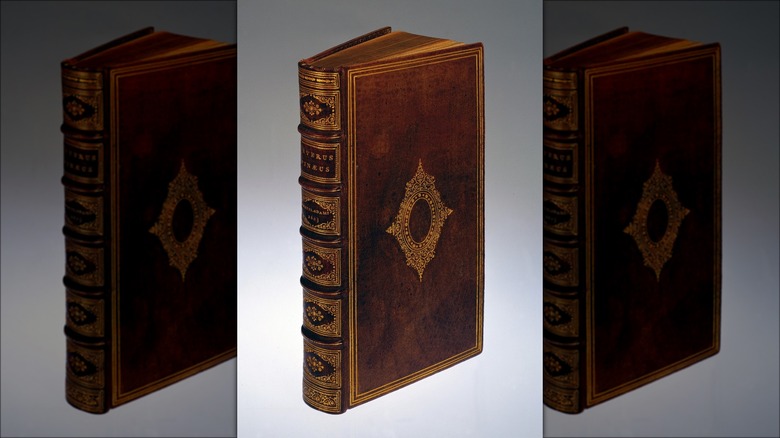

Why would human skin books be created in the first place? It's not as if obtaining the raw materials for such a project was an easy proposition, even in the seemingly lawless world of early modern medicine. And possessing such a volume was a dubious accomplishment, at least as far as many people were concerned. So, what was the purpose of having such a ghastly object in one's private library? Status, for one. According to Lapham's Quarterly, having a book bound in human skin was an indicator that someone had the resources to not just commission a custom-bound book but also use some truly unique materials to do so. What's more, the book could show that its owner was part of the upwardly mobile medical profession, which saw its prestige rise from that of a gory sawbones to a highly desirable career and social status over the 18th and 19th centuries.

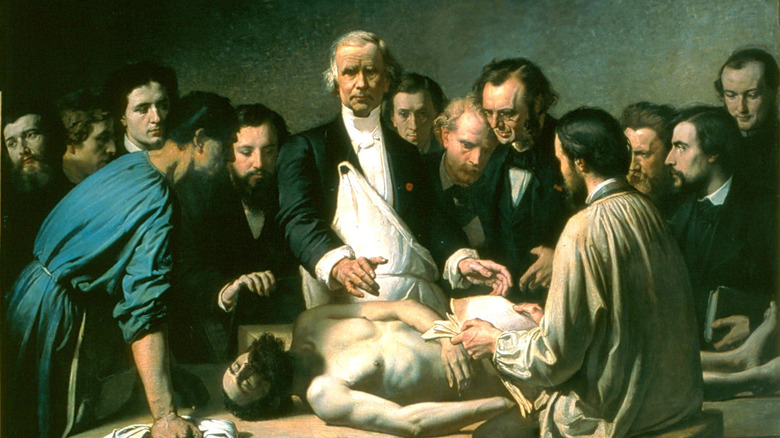

Then, there was always the matter of deterring crime. After their execution, some criminals (including high-profile evildoers like William Burke) were cut down from the gallows and then promptly dissected. The disassembly of their remains was meant to be yet another punishment, making a spectacle of their corpse when the last remnants of good folk were buried in the ground instead. After that, a convict's skin might then be removed, preserved, and used to bind a book in yet another postmortem humiliation, forever to be remembered in horror.

Many supposed human skin books are misidentified

Lest you think our skin is anything special, it doesn't look all that different from animal hide when it's been tanned and stretched across a book's binding. This has led to quite a few misidentified books, whispered about by librarians and patrons, unsure if the book they're handling belonged to someone else in more ways than one. The truth, in many cases, is that the stories are too shaky to stand up to reality. That's because the scientific investigation of quite a few purported human skin books shows that they are actually bound in non-human animal skin (via Lapham's Quarterly). While there are certainly some human skin books out there, the fantastical stories associated with some are larger than life and not necessarily verified.

Take the case of one book that was supposedly owned by Christopher Columbus. As Notre Dame Magazine reports, it was said to be bound in the skin of a "Moorish chieftain." The story, which came through a dubious chain of book traders in the early 20th century, became a favorite of Notre Dame students, tour guides, and other curiosity-seekers. Newspaper accounts of anthropodermic bibliopegy were even glued to the inside cover of the book. Yet, when librarians consented to have the book's bindings tested, the collagen in the binding appeared most likely to have been sourced from a pig. Likewise, another supposed example of anthropodermic bibliopegy at Harvard was found to come from another barnyard animal: a sheep.

Scientists test book bindings for human collagen

If it's so difficult to visually determine whether or not a binding is made from human skin, then how do researchers actually figure it out? As Notre Dame Magazine notes, the bindings in many books are far too old to contain intact DNA. What's more, bookbinders of old probably didn't keep separate containers for different animal skins, further contaminating the sample centuries later. Genetic testing, which would be a scientific slam dunk in other cases, is a pretty poor choice when it comes to identifying old book bindings.

The answer comes in the form of peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF). According to the Anthropodermic Book Project, whose members use this form of testing, this method isolates protein from collagen found in the bindings. Unlike DNA, which can degrade relatively quickly, collagen can remain stable for a very long time under the right conditions. Using enzymes, researchers break down a sample of the binding and test the mixture for ions that are unique to a species or group of species. With this method, PMF can tell you if a binding is derived from a hominid, though it currently can't get more specific. Still, that's more than enough for scientists who test these bindings. Given that there are very few tales of books bound in gorilla, chimpanzee, or other wild hominid skin, that really only leaves one other great ape: humans.

Some books are linked to criminals

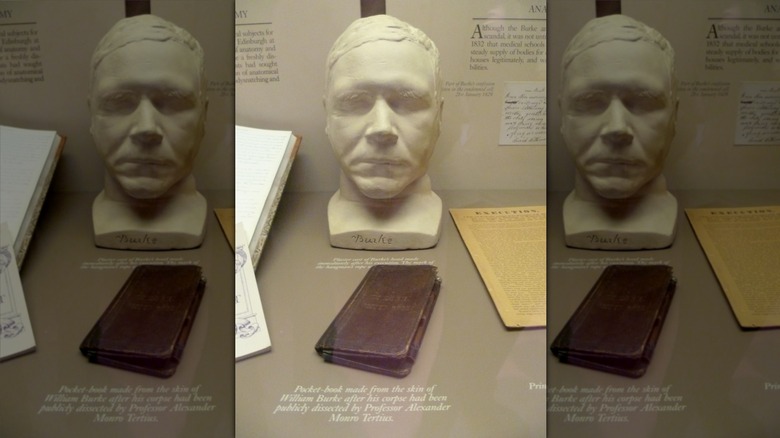

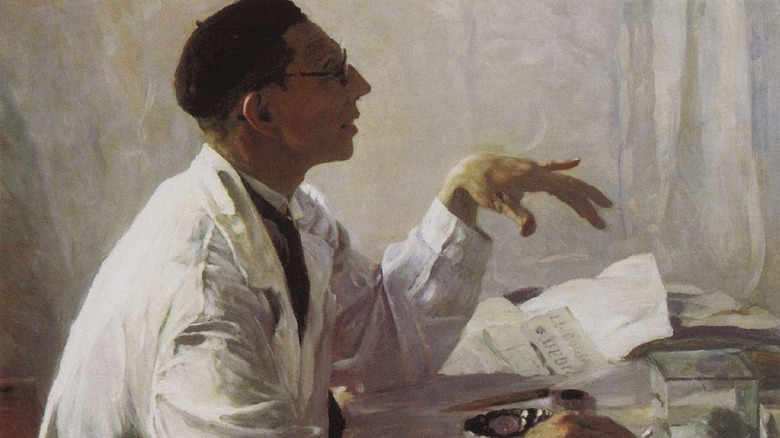

Some of the most striking tales of books bound up in preserved human skin are linked to notorious criminals. Being turned at least partially into a volume that outlined one's heinous misdeeds was seen by some as a uniquely gruesome — if fitting — punishment. At least it was for the likes of William Burke. As one half of the infamous Burke and Hare duo, he helped supply human remains to the anatomists of 19th century Edinburgh. According to the University of Edinburgh, Burke and Hare typically worked with Dr. Robert Knox. Only while other so-called "resurrectionists" dug in local graveyards, Burke and Hare's supply was fresher. They're believed to have murdered 16 people, whose remains they then sold to Knox's anatomy school.

After his 1829 execution, Burke's remains were publicly dissected, as the BBC reports. At this point, some amount of his skin was removed and later turned up around a small book, now in the possession of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Burke's skeleton and death mask are also on display in Edinburgh, as the University of Edinburgh reports. The anatomist who dissected him even dipped a pen in the criminal's blood and wrote a sentence out in the stuff. As for Burke's accomplice William Hare, there's no clear evidence of what happened to him, though it's possible he was also executed. Perhaps there's another ghoulish book out there with something more than his name on it.

Consent gets murky when it comes to human skin books

In the not too distant past, consent was little more than a word for doctors and researchers. There was science to be done, after all, and the prevailing notion was that advancements in medicine trumped an individual's wishes, both in life and beyond. Human skin books often came about in a world before consent forms were common. Take one example held by Philadelphia's Mütter Museum. This book, confirmed to be bound in human skin, was created after the 1869 death of Irish immigrant Mary Lynch, who had died of tuberculosis. A doctor removed it, seemingly without ever bothering to get Mary's permission prior to her death, and used it to bind a medical text. In fact, he went on to bind three books with her dubiously-acquired skin (per The New York Times).

Some of this ethical line-crossing likely has to do with the rise of the medical arts, says Lapham's Quarterly. As author Megan Rosenbloom argues, the professionalization of medicine after the gory days of the French Revolution led to a widespread depersonalization of patients and bodies. Human beings became discrete cases, examples of syndromes or illnesses that could be entered in textbooks rather than unique and complicated individuals who might protest at the idea of being turned into a literal book. It could have made it all the easier to see them (or their remains) as raw materials, prime for the taking.

Doctors are often behind books bound in human skin

As it turns out, quite a few of the confirmed examples of human skin books are medical texts. Mary Lynch's skin was used to bind "speculations on the mode and appearances of impregnation in the human female," for instance (via Mütter Museum). That points pretty obviously to the sort of people who made these books. They weren't criminals themselves, nor were they muttering occultists. Instead, they could well have been your local doctor.

Though, as The New York Times reports, human skin books were never as common as some tales would have you believe — they were created by a preponderance of medical professionals. But why were doctors more likely to be behind these gruesome works of literature as opposed to, say, bookbinders? For one, they had greater access to the raw materials. They were also arguably more inclined to hold patients at an arm's distance, using that level of removal to see the human in front of them as more of a set of conditions or materials instead of a living, thinking being. It's also worth remembering that medical ethics is a fairly new field. When many of these books were assembled in the 18th and 19th centuries, the idea of getting consent — or of suffering any real consequences for failing to do so — appears to have skipped doctors' consideration entirely.

Some books can be linked to a specific donor

Many books confirmed to be bound in human skin are frustratingly anonymous. But there are a few examples that give us haunting details of the human life that preceded the book. We can easily track down at least a couple of volumes bound in the skin of criminals, from body snatcher William Burke (via the University of Edinburgh) to William Corder, a notorious murderer whose remains were likewise used to cover a book after his 1828 execution (via the BBC).

But not all of these books are linked to punishments for the deceased. Though medical records can be sketchy, one book from 1869 is pretty clearly linked to a woman named Mary Lynch. As the College of Physicians of Philadelphia tells it, Lynch was recorded as having entered the Philadelphia General Hospital in July 1868. The hospital's register indicates that she was an Irish immigrant and had a form of tuberculosis. She must have also been poor, as the better-off could go to other treatment facilities. After six months, she died in January 1869, weighing only 60 pounds after her illness ran its course. Having friends who brought her food but seemingly no money, she was buried in a grave on the property.

Dr. John Hough autopsied her remains and removed skin from her thigh, tanning it himself in the basement of the hospital. He then held onto the results for decades, finally using Lynch's skin to bind three books in 1887.

Many disagree about what to do with human skin books

Let's say you're a rare books librarian with a suspected example of anthropodermic bibliopegy in your collection. You offer it up for scientific examination and soon learn that the peptide mass fingerprinting has confirmed the rumors: you've got a human skin book on your hands. Now what? The next steps in this process have proven highly contentious in the world of anthropodermic bibliopegy. Ultimately, you need to either keep the book in your institution's collections or dispose of it.

Some researchers, like Megan Rosenbloom, maintain that we should keep these books around, no matter how much they creep us out. In fact, they may be even more important because of that very fact. According to her, they remain useful not just for research purposes but also as a reminder that even seemingly "normal" people in trusted positions can do unnerving things (via The New York Times). Others argue that these books should be treated like any other human remains and given a decent burial or cremation. Consider William Corder, the 19th-century murderer whose skin was harvested after his execution and used to bind a book. As the BBC reports, a descendant of his successfully lobbied for the return of Corder's skeleton remains from the Royal College of Surgeons, though his scalp and the book covered by his skin remained in academic hands. So far, the decisions are generally left to the librarians and curators in charge of these exceedingly strange volumes.