The Untold Truth Of The Salem Witch Trials

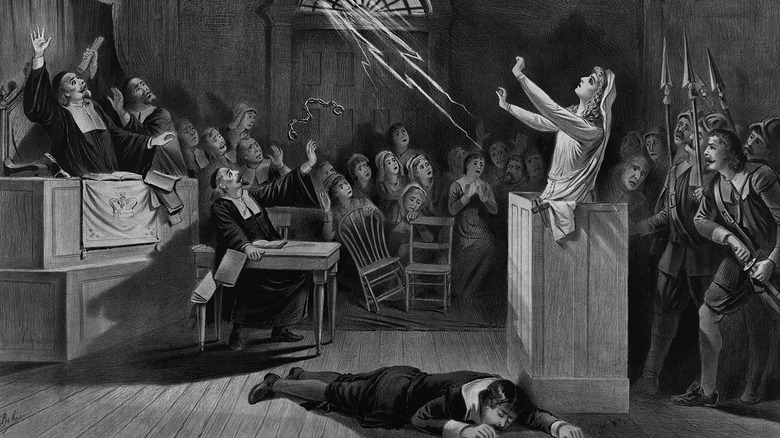

In 1692, the Puritan village of Salem, Massachusetts, was hit by a wave of zealous religious paranoia. People accused their neighbors, friends, and their own family members of joining forces with the devil. Hysteria burned through the community, and in seven months, more than 200 people had been accused of witchcraft, 20 innocent people had been murdered, and five more had died in prison.

There were never any witches in Salem — so why did a devout community suddenly become convinced that there were? Why the town of Salem fell victim to mass hysteria, believing that Satan walked among them, corrupting people they had known their entire lives, has fascinated people ever since.

The modern town of Salem, Massachusetts, is a tourist destination. It features fortune tellers in pointy witch hats, gift shops full of what Atlas Obscura dubbed "witch kitsch," and even a statue of Samantha from "Bewitched." Tourists are invited to put their faces in large plywood cutouts of witches. The high school's mascot is a witch. October transforms the town into a month-long festival celebrating witches. All of those executed were Puritans who refused to pretend to be witches and "confess" to crimes they had never committed, even though it meant their deaths. Many consider the town's approach to their history disrespectful to those who died — but at least the town's decadent embrace of the idea of witchcraft would shock and horrify those who committed gruesome acts of violence to keep witchcraft out of Salem.

Salem wasn't the first witch hunt

The Salem witch trials have become synonymous with religious fervor and paranoia leading to violence. But it was far from the first time that communities have become convinced that malevolent supernatural beings were living amongst them, or that their friends and neighbors might be in league with the devil.

More than 200 years before Salem there were similar trials in Europe. As described by "The European Witch Craze of the 14th to 17th Centuries: A Sociologist's Perspective," there were witch trials throughout Europe, starting in the 14th century. It is believed that between 200,000 and 500,000 accused witches were executed, and as stated at History, some of these were looking for another supernatural entity: werewolves. It is believed some may have been guilty of actual crimes, but the majority were scapegoats. Many of the accused were outsiders in their communities, and only confessed when tortured. These were not fringe actions taken by superstitious townsfolk; these trials were conducted legally by legitimate courts across the continent. In 1521, the Pope himself presided over three werewolf trials, leading to two executions.

There were even witch trials in America prior to Salem. As described in "Connecticut Witch Trials: The First Panic in the New World" (via Connecticut Magazine) there were witch trials in Connecticut as early as 1647. Connecticut's witch hunt lasted 45 years, while Salem's was only 7 months. In that short time, however, Salem accused and executed more people than in all of Connecticut's decades.

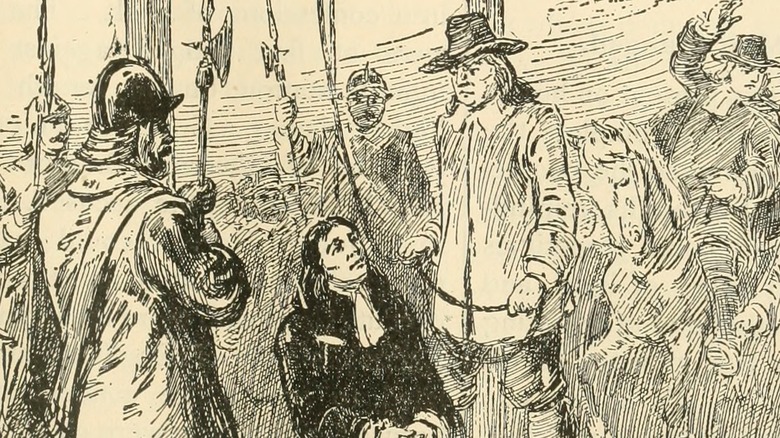

No one was burned at the stake

Paranoia about witches living amongst them led the people of Salem to legally sanction murder. Many modern depictions of witch trials show those suspected of witchcraft being burned at the stake. In reality, though, none of those killed in Salem were burned — but they were killed in other ways.

As described by History, the myth about burnings at Salem is very likely from European witch trials. Although no one suspected of witchcraft was ever burned in Salem, it was common in Europe. In fact, it was even cemented in medieval law that witches should be burned — though many were killed in other ways and burned after death.

Of the 20 people executed in Salem, 19 of them were hanged. The 20th person was executed by the hideous torture known as "pressing," which was a process of crushing someone to death. Several other people of Salem who had been accused of witchcraft died in jail.

Some people blame the trials on mold

The people of Salem seemed to start experiencing mysterious symptoms and blaming their neighbors for them overnight. The events that followed have shocked and horrified people ever since. Some have looked for physical explanations for the panic.

In 1976, Dr. Linnda Caporael, a behavioral scientist, proposed an explanation. As described by Britannica, Caporael suggested that the cause was actually ergotism. The fungus ergot grows on rye, causing dark purple growths. At the time, it wasn't understood to be dangerous, so it would likely still have been eaten. Eating the fungus can cause extreme hallucinations and delusions, along with convulsions and other physical symptoms.

As described by the Washington Post, however, the truth is not so simple. While some of their symptoms are similar to ergot poisoning, many of the accusers described the same visions, making hallucinations almost impossible. The physical symptoms, like seizing up, did not get worse over time as one would expect with repeated poisoning. Instead, they seemed to react to specific stimuli, like seeing the "witch" or touching religious items. As horrific as the idea of dozens of people eating a toxic substance is, the likely truth is even more disturbing: through groupthink and religious mania, normal individuals were driven to persecute and murder their friends and neighbors.

The Devil was ever-present in Puritan life

It might seem absurd that otherwise ordinary people would become convinced that the people they had known for years, even their own family members, had forged pacts with the devil, but for Puritans the devil was a constant threat. As described in "Connecticut Witch Trials: The First Panic in the New World" Puritans like those who lived in Salem considered everything that happened in their lives, from floods to sour milk, to be the work of either God or the devil. In their sermons, ministers warned about the constant temptations that the devil would present to even good and holy people. The people of Salem believed that the devil was a constant threat that was always working to pull them towards evil.

As described in the New Yorker, Puritans believed that people who were tempted by the devil would become witches, entering into a pact with Satan. In fact, the second capital crime that was established for the colonies was witchcraft. As stated by Britannica, Puritan faith was devout and had strict moral rules that had to be followed in every aspect of life. In a society that believed so strongly that the devil was walking among them and working evil, that also had such a strict view of morality that applied to everyday life, it's not unthinkable that a moral panic would spread.

Salem's minister was a driving force behind the trials

Puritan faith may have been devout, but shortly before the witch trials, a new reverend arrived in Salem who was too zealous for many in the community. His name was Samuel Parris, and many have linked his preaching to the religious fervor in Salem that resulted in numerous deaths and more accusations.

As described in chapter 7 of "Salem Possessed: the social origins of witchcraft," Samuel Parris came to Salem to become their minister, and although he began preaching at once, he refused to officially accept the position. He continued to negotiate for a higher salary, and sent more and set highly specific terms of employment. The community came to resent Parris's demands, and the negotiations took some time. As described by Tulane University, the church at Salem was welcoming to outsiders and accepted less devout members than other churches. Parris made the church more strict, and he preached far more rigid doctrine. The community was divided between those who supported the new reverend and those who didn't. Less people went to church, and some tried to cause issues for Parris. Taxes for church salaries became voluntary, and officials in the village refused to provide Parris with firewood. As described in the New Yorker, this was a particularly aggressive tactic, because in 1691, it was dangerously cold. Soon, Parris was preaching that there were devils and witches all around them.

The first accusers were children

Samuel Parris had a 9-year-old daughter Betty and an 11-year-old niece Abigail. As stated by History, it is believed that the girls were playing a fortune-telling game with an egg when they began acting strangely. As described in the New Yorker, Abigail and Betty began telling their family that they were being bitten and pinched. They babbled and spun in circles. They went alternately shaky and still. They called out during Parris' sermon. The girls were given a diagnosis, but to the people of Salem the cause was obvious: the girls had been bewitched.

One might think that having his own daughter beset by witches would reflect badly on Parris, but it actually raised his status. The devil attacking children in Salem was evidence that the people of Salem were particular enemies of the devil. It was evidence that they, and Parris and his family, were on the side of God. As quoted in "Salem Possessed," Parris would later call it humbling that God chose his family.

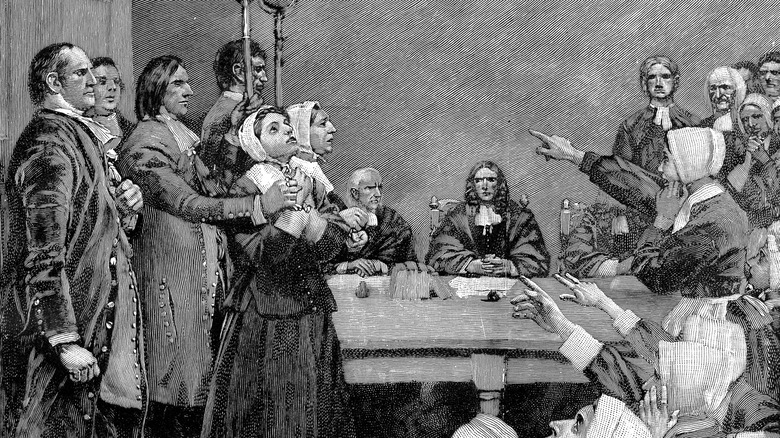

It didn't take long for the perceived affliction to spread. Soon other girls and a few young women were exhibiting similar symptoms, and claiming to see mysterious creatures following them. It was believed that witches were attacking them. Adults questioned them, insisting that they reveal who was attacking them with magic. Ultimately the girls agreed on three names: Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne, and Tituba. All three women were brought to a public examination to determine if they were really witches.

The bizarre role of baking

Tituba, one of the women who Abigail and Betty claimed was responsible for their symptoms, was enslaved, and worked for Samuel Parris and his family. It's unknown exactly why the girls targeted her, but one reason is that she had been ordered to do some peculiar baking by the Parris' next door neighbor, Mary Sibley. As stated by Atlas Obscura, Sibley believed in an old folk practice for warding off evil. She believed the only way to counter witchcraft's effects was a different type of magic: a witch cake.

When the Reverend Samuel Parris was away, Sibley ordered Tituba to create a rye-meal cake with some unusual ingredients — ashes and urine from the afflicted people. As explained by History, Sibley believed that if Tituba fed the cake to the Parris family dog, it would tell them who the witches who had cursed the girls were. Tituba had no choice but to follow Sibley's instructions.

The dog did not reveal the names of Salem's witches, and the girls did not recover. When Samuel Parris found out what Tituba had done, he was furious. He believed that the witch cake was satanic, and in one of his sermons, he told the town that the cake confirmed his fears that witchcraft was rampant in Salem. Sibley herself repented and was never charged with witchcraft. Tituba, however, who was only following Sibley's instructions, was arrested on suspicion of witchcraft.

The woman whose testimony defined witchcraft is still a mystery

Despite her role in the story, not much is really known about Tituba. It is likely that she was captured and trafficked when she was still a child. She may have been an indigenous Central American who was taken to Barbados and sold to Samuel Parris. She was a teenager when he brought her to Salem. It is believed that she married an enslaved man named John, and that they had a daughter named Violet (via History). As described by Smithsonian, it is believed that Tituba would've spent the majority of her time caring for Betty Parris.

Parris was furious about the witch cake, and Tituba eventually agreed to confess. As seen in the transcript of Tituba's examination by the court, she vehemently denied that she had done anything to hurt the children. When they wouldn't accept it, her story changed.

Tituba told the court that she had been forced to harm Betty and Abigail by a terrifying creature that was somewhere between a massive black hog and a dog. She described a pair of cats, one black and one red, that had demanded she obey them. She said that she and the other witches rode through the sky on sticks. She named Sarah Good as a fellow witch, who had fed a strange yellow bird her blood, and Sarah Osborne, who had carried a winged creature that could shapeshift. Tituba's incredible testimony was used as hard evidence of witchcraft, and led to many deaths in Salem — but Tituba actually survived.

One of the first accused was a homeless woman

Sarah Good was one of the other two women that Abigail and Betty accused of witchcraft. Unlike Tituba, she was a free woman, but she was also a vulnerable person in the community.

Sarah Good was born into a relatively well-off family, but after her father died, her mother's new husband kept her and her siblings from inheriting almost all of their father's land. As stated in "Salem Possessed," Sarah married an indentured servant with a large amount of debt. When he died, she inherited all of his debts. Even after she remarried (to a man named William Good) creditors continued to pursue repayment. The Goods were forced to sell their home and rely on other members of the community for food and places to sleep. Some in Salem, including Samuel Parris, considered Sarah Good ungrateful for their charity. As noted in "The Devil in the Shape of a Woman," no one spoke up for Sarah Good when she was accused of witchcraft. Her own husband joined her accusers, stating that he feared Sarah, "was a witch or would be one very quickly."

Sarah Good had a young daughter, and she was pregnant with another child when she was taken into custody. As detailed in "Salem Story," the Puritans would not execute a pregnant woman, so they waited until she gave birth. The infant died in prison, and Sarah Good was hanged.

One of the accused was 4 years old

Among the flurry of accusations that followed the first three was one against Sarah Good's daughter Dorcas (or Dorothy.) She was only 4 years old. As depicted in the court transcripts, several older girls, including Ann Putnam, Jr., (age 12) and teenagers Mercy Lewis and Mary Walcott accused Dorcas of choking them, pinching them, and urging them to sign the devil's book. During the child's examination by the court, many people claimed that they were in pain whenever Dorcas happened to look at them.

Dorcas was sent to prison, where she remained for just under nine months, often chained up (via "Salem Story"). She survived. When Dorcas was 22, and the trials were long over, her father William Good stated that she had never fully recovered and had, "ever since been very changeable" (via "The Salem Witchcraft Trials in United States History").

Ann Putnam, whose family members had also accused Dorcas, would grow up to regret what she had done. When she was 29, she confessed (quoted via History of Massachusetts) that she had accused people of terrible crimes and some of those people had been killed. She believed that she had been deceived by the devil. She would live less than 10 more years after her confession. It has been theorized that Ann had a chronic illness that was responsible for her early death, and it's possible that she was suffering from symptoms of this condition at the time she accused young Dorcas of hurting her.

Not all the victims were women

In modern times, the word witch is often used to describe a woman, but in Puritan Salem, witches could be men, women, and even children.

Good Puritans were expected to live a simple life and never give into temptations to live in a more pleasurable way. As described in "Connecticut Witch Trials: The First Moral panic in the New World," Puritans felt that the devil was always trying to tempt them away from God, like in the story of Adam and Eve. They also believed that, like Eve, all women were susceptible to temptation. Likely because of this belief, most of Salem's accused witches were women.

Despite this, multiple men were accused of witchcraft in Salem. One of these was Giles Corey. According to History, Corey was 81 years old when he was accused of witchcraft. As detailed by "The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-by-day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege," Corey was excommunicated from the church, but refused to stand trial for witchcraft. He was "pressed," a horrific torture that crushes the victim under rocks. The intention was to force Corey to plead innocent or guilty, but instead it killed him without a trial. It is believed that he may have accepted this extremely cruel death because it allowed his family to inherit his estate. If he had been convicted of witchcraft, it would have been seized.

Devil's Marks were used to convict accused witches

The people of Salem were convinced that there were people doing the devil's bidding in their community, which left them with the task of figuring out who among them were witches. Often, they looked to common beliefs about witches to narrow down their suspects. As described in "Cry 'Witch': the Salem Witch Trials, 1692," it was believed that witches participated in devil-worshipping masses, spread their beliefs to their family members, and were assisted by demonic familiars.

Puritans thought that when witches joined forces with the devil, they signed his book in blood. After that, it was believed that the devil would give his new servants a familiar: typically real creatures like snakes, cats, and birds, but sometimes supernatural creatures such as imps. According to legend, witches had to feed these familiars some of their own blood — and that left a mark.

Puritans on a witch hunt would force accused witches to undergo a strip search for Devil's Marks. They would search the person's body for any place they thought a familiar might have fed. Any birthmark or freckle was suspect. Sometimes they would pierce those spots with pins, believing that witches would feel no pain.

Spectral Evidence was used to convict the accused

While Salem is often described as group hysteria — which is an accurate description in many ways — the process that the community used to accuse and execute witches was entirely legal. The court took accusations of witchcraft extremely seriously. As described in the Library of Congress, many of the convictions were based on "spectral evidence."

It was believed that the devil gave witches the ability to travel outside their bodies and appear to their enemies. They were even thought to be able to attack people while in this ghostly form, so the court was looking for proof that someone was able to use this type of magic. Because of this, they considered dreams and visions to be valid evidence. Spectral evidence refers to witness testimony about said dreams or visions they had. For instance, if a person had a dream that their neighbor threatened them, that dream could be used as evidence against the neighbor.

However, even some who believed in witchcraft felt that using spectral evidence to get a conviction was a mistake. Per Britannica, Cotton Mather was a famous minister who believed in witches — but he wrote to Salem's judges warning them against trusting spectral evidence. He feared that the devil might take the form of innocent people to trick people into thinking they were witches. Despite these concerns about the validity of dreams and visions, spectral evidence continued to be used in Salem against accused witches.

People testified to seeing impossible things

With spectral evidence allowed as testimony, many members of the community came forward to tell incredible and terrifying stories about their family members, neighbors, and friends. During the examination of Sarah Cloyse and Elizabeth Proctor, the deputy governor Thomas Danforth told the court that the women had come to him many times, grabbing him by the throat, pinching him, and biting him until he bled. Ann Putnam said much the same thing about young Dorcas Good — that she had come to her as an apparition and choked her, trying to force her to sign the devil's book. In the deposition of John Allen v. Susannah Martin, Allen claimed that he had attempted to throw Martin into a brook, but she escaped by flying away. In the deposition of Thomas Bailey v. John Willard, Bailey said that he had gone looking for Willard because he had heard that he was beating his wife. As Bailey approached, he claimed he heard the terrifying sounds of evil spirits.

Tituba's story, however, was probably the strangest. She claimed that a man, dressed in all black with white hair, had come to her and commanded her to serve him. Sometimes he came to her in the form of a demonic hog, and sometimes as a big black dog. A pair of cats commanded her to serve them, and she was told to kill Abigail and Betty. She also described an upright hairy creature that set wolves on the people of Salem.

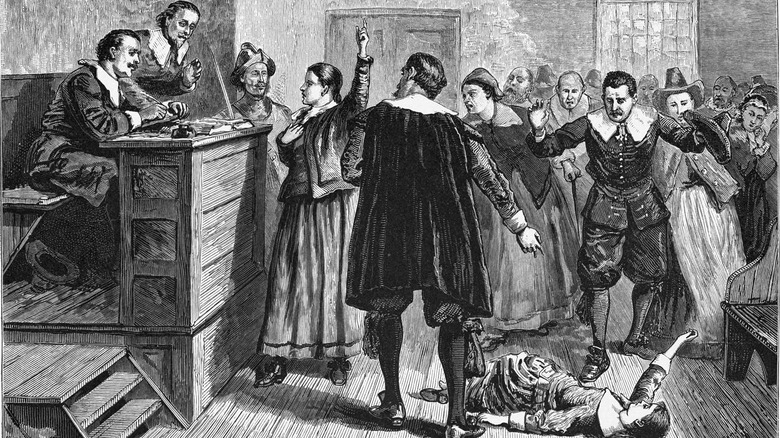

Saying you were innocent could get you killed

As Tituba discovered through her confession (via the Smithsonian), if neighbors and former friends began lying about someone and saying they were in league with the devil, sometimes the safest thing for the accused witch to do was to agree and ask forgiveness.

As explained in Britannica, there was no way for an accused person to get a fair trial. The accused had to represent themselves, without help. Their friends and family members were often afraid to speak out, in case the community decided that they were witches, too. As well as allowing dreams and visions as evidence against them, they were questioned in front of an audience, and many in the audience would start screaming and writhing in pain when the accused looked at them — which was also considered evidence that they were guilty. People who insisted that they were innocent, and had never performed evil magic to hurt anyone, were often punished harshly or killed.

If the accused was willing to pretend that they were witches and repent, asking for forgiveness, they were generally allowed to go free, because Puritans believed that God would punish them as they deserved.

The people of Salem executed their former minister

Minister Samuel Parris' niece Abigail had an explanation for the outbreak: the town's former minister George Burroughs. As described in "Salem Possessed," Burroughs was no longer in Salem — but that didn't stop the community from charging him with witchcraft.

Abigail officially charged Burroughs with being the first in Salem to serve the devil, and to convert others to the diabolic cause. Burroughs now lived in Maine, but he was brought back to Salem to stand trial. As stated in Britannica, he was hanged there.

At the time, it was believed that because witches had turned away from God, they were unable to correctly say prayers. Before he was hanged, Burroughs said the Lord's Prayer. The townsfolk who had gathered to watch the execution started to doubt that he was actually a witch. Cotton Mather (who had spoken out about the use of spectral evidence, per the Library of Congress) encouraged them to kill Burroughs anyway.

The Protagonist of The Crucible was a real person

John Proctor is the protagonist of the famous Arthur Miller play, "The Crucible," but he was also a real man executed for witchcraft in Salem. As stated in "The Crucible of History: Arthur Miller's John Proctor" Miller stated that he had fictionalized Proctor and his wife more than any of the other characters. Unlike his depiction in the famous play as a young laborer, Proctor was actually a wealthy man in his 60s when he was accused. As described by UMKC, Proctor was physically very large and imposing and was prone to rash decisions. He spoke his mind about everything, including the trials.

From the first accusations, Proctor argued that Betty, Abigail, and the others were lying. It is believed that he also beat his servant, Mary, when she started claiming that she was afflicted by witches. When Proctor's wife was accused, he vehemently argued that she was innocent, leading others in Salem to believe he was also in league with the devil. Soon, there were multiple accusations against Proctor. Some, including Ann Putnam, accused Proctor of appearing to them as an apparition, pinching and choking them, and trying to force them to sign the devil's book. One woman accused him of crushing her and forcing her to drink blood before vanishing into thin air.

Proctor was the first man accused of witchcraft in Salem. He was executed just below the infamous Gallows Hill (via the Smithsonian).

Gallows Hill was the site of many executions

The majority of those accused of witchcraft in Salem were killed on a ledge below Gallows Hill. As described by Smithsonian, there were three mass executions under Gallows Hill, specifically on a rocky ledge. Those killed there included Sarah Good and John Proctor. The ledge is now known as "Proctor's Ledge." A total of 19 people were murdered there.

Those who were convicted in the Salem witch trials were brought to Proctor's Ledge under Gallows Hill and hanged from the trees. After they were killed, the bodies were dropped off the ledge. The spot where the bodies were dropped was known as "the crevice." Although they were thrown there without ceremony, the families of those killed were known to secretly come to the crevice in the middle of the night to collect their loved ones bodies. Where they were ultimately buried is unknown.

In 2017, a monument was built on Gallows Hill, honoring those who had been killed there.

Not everyone in Salem was behind the trials

It was more difficult to speak out against the trials from inside the village, as John Proctor learned. It is impossible to say how many of the people in Salem who went along with the trials actually believed those they executed were guilty, and how many were afraid that they would be targeted if they resisted — but after the trials ended and there was less risk of being accused of witchcraft, many more Salem residents condemned what had been done.

As noted by National Geographic, when Governor Phips' wife was accused of witchcraft, he put a stop to the trials. Phips prevented the use of spectral evidence, which made it almost impossible to convict someone on witchcraft charges. He ultimately pardoned all the accused witches in prison. In time, some of the victims' families were offered compensation.

As soon as the threat of violence had decreased, more people spoke out against Reverend Samuel Parris. The church records (quoted via History of Massachusetts) show that many stopped going to church, citing Parris' involvement with the trials, and saying that they felt unsafe attending. Parris would eventually ask forgiveness from the congregation. While he continued to have many supporters, there were vocal critics. It is believed that three years after the trials ended, he was finally forced to leave the Salem parish.